How can community engaged art practices foster authentic and mutually beneficial relationships?

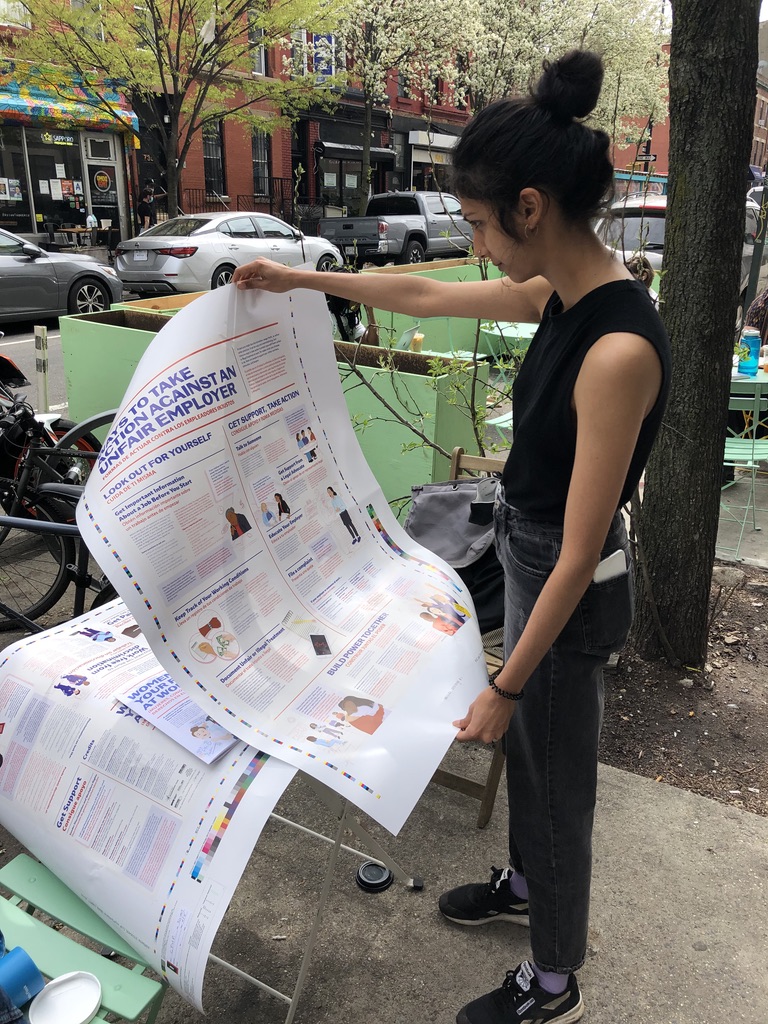

Siyona Ravi is an artist and art worker based in New York whose practice centers on using art as a tool for advocacy and building solidarity. She is currently a Program Coordinator for the Center for Urban Pedagogy, a non-profit that works with designers and community advocates to make educational tools that increase civic engagement and make complex policy issues accessible. A former Create Change Fellow at the Laundromat Project and a former NYC Engagement Coordinator for the Fundred Project, an initiative led by artist Mel Chin to raise awareness about lead poisoning, Ravi often plays the role of a facilitator, collaborating with communities on long-term projects. We spoke in January 2022 and our conversation was condensed and edited for clarity.

HANNAH FAGIN: How did you first become engaged in collaborative and community driven art practices?

SIYONA RAVI: I’ve always been interested in art and in social movements and community organizing, but I was introduced to them separately. The more I started learning, the more I could see how interconnected art and community organizing are. Historically, art has played such a huge role in raising consciousness and in movements for social change.

I feel so lucky I get to learn from people who do this work and now I get to do it for a living. A formative experiences was right out of college, when I worked with Anandam, a queer and trans branch of a sex workers union in Kolkata, India. As an undergraduate, I did research on the labor union, Durbar, where I learned that over 60,000 sex workers collectivized to form a labor union, and how this organizing became a social movement in itself. Building on this research, I joined them after graduation to work on creative advocacy campaigns to repeal a law that, at the time, criminalized sodomy in India. Together, we came up with an idea to make a short film showing how this law has impacted members’ lives, interviewing lawyers, police, and other stakeholders. We also worked on a photography campaign with several other members of Anandam. The project was truly collaborative at every stage, which was often quite challenging, but really brought us all together. Members of Anandam art-directed themselves and decided how they wanted to be portrayed in the film and in photos. They invited us into their homes and spaces where they worked and then directed their own scenes.

On an individual level, the project created the space for community members to express themselves and be presented the way they want to be–a real reclaiming of power. This project was also part of a national campaign to repeal the sodomy law, so we were really working to build solidarity in the service of this bigger goal. This was the first time I could really see how art’s role in creating change could very much come from the needs of the community.

What have you learned from your experiences working as an artist and facilitator with nonprofits like the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP), the Laundromat Project, and the collective initiative, Fundred Project?

It’s not about coming in as outsiders with our own solutions to a community’s problem. It’s about getting to know the community and taking their lead. Especially coming from the non-profit side of things, organizations like the Laundromat Project and CUP have really created an infrastructure and a process for how art can be used to build community and solidarity. A lot of it is about showing up, and building trust. From a logistical standpoint, you have to budget time for this. Relationship building has to be a priority and that ultimately shapes the work.

There’s a long history of artists and arts organizations coming in with a savior complex and causing harm to communities. There’s a lot of ways to address this, but at CUP, we explicitly follow a resource ally model to support communities in the work they’re already doing and follow their lead about what the solutions are. It’s not about the artist who comes in, it’s about the work itself and the people.

How do you build a shared vision in a collaborative project? How do you handle moments when different groups have competing interests or disagreements arise?

This is a hard question but it’s also the most important part of the process. Everyone needs to get what they want from a project on the table. From there you scope it down or up, depending on what your budget, timeline, and capacity is.

Disagreements are inherently part of this process. We need to lean into them and not worry that if a disagreement arises the project can’t move forward. If we have the tools and set up a space where people feel listened to and comfortable sharing, and the collective goals are agreed upon, then disagreements can be really fruitful moments. Working through tension is a form of relationship building and brings a critical lens to the project. Sometimes it’s about compromise, sometimes it’s about putting your ego aside; stepping back and understanding that it might not always go the way you expected is a big part of the process. You may have to let go of your personal vision for the sake of the shared one.

What are the limitations of using art as a means of community building?

Art isn’t magically going to transform everything. It can help us reimagine the world we want to build, raise consciousness, bring people together. It can help people heal and connect with others. But you still need to keep that momentum of change going. You need to do the work of building that change and that new world. This could be at the policy, individual, or grassroots level. It’s always an ongoing process and art can be the starting point, the endpoint, or just the process.

What does authenticity look like in a community engaged practice? How can artists work authentically and non-exploitatively with their audiences?

Part of this is not coming into a project with your own solutions and realizing the project can go in different ways. There is a deep history of artists or organizations coming in with a savior complex and parachuting in with a project and then leaving. There’s so much work that has to happen before entering a community. The Laundromat Project has a thoughtful way of approaching this. They call it “Entering, Building, and Exiting.” It’s about thinking through your role and impact as an outsider. So, being really intentional about how you enter the community and build trust, how you sustain the relationships, and then thinking through what happens after you leave, once a project is over. Are you sure you aren’t abandoning the community you’ve worked with? That often happens—you get funded to do a project for a certain amount of time and when it’s over, that’s it. How do you transition out in a way that is sustainable and that leaves people in a place where they can still maintain the project if they want to? Part of this may be about sharing and transferring ownership of the materials and resources, making sure that people have access and can make the necessary decisions.

With the Fundred Project, Mel [Chin] goes back to all the cities he’s worked in. That’s why these relationships have been going on for so long. I remember talking to some folks he was working with in New Orleans and in Flint, Michigan, and they said, “When we met Mel, we thought he would be another artist who came in, did his project, and left. But he keeps coming back, so that’s why we’re still here.” The authenticity comes from the relationships we’re building and a commitment to the people, the issue, and the place. There’s so much love for everyone involved, and this goes far beyond the scope of the initial project.