German Art of the 1920s at Centre Pompidou

IT WAS SOMEWHERE WITHIN THE FIRST 10 rooms of the Centre Pompidou’s daunting exhibition on German art in the 1920s that I overheard a few people bracing themselves for the rest of this nearly 30-room, 900-piece show: “Mais c’est énorme.” “Je n’en suis pas capable!”

Simply naming it “Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander,” the show’s curators seem to have lost stamina when coming up with a catchy title for the multimedia monster they’d mounted in the museum’s top-floor Galerie 1. More likely, however, they knew their show would speak for itself as an “exhibition within an exhibition,” where works of painting, sculpture, design, film, music, literature, and more encircle an expansive survey of the master photographer August Sander. Sure enough, by the time you’ve made it to the full reconstruction of one of Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s Frankfurt kitchens (whose compact, counter-based layout is now a given of urban dwelling), it’s clear you’re in a Gesamtkunstwerk of curation.

The first two pieces of the exhibition hang in a small corner nook: A 1913 self portrait by the Expressionist painter Ludwig Meidner and a 1914 photograph by Sander, Young Farmers. Meidner paints himself dark and distorted, as if on the verge of fading from view, while the strolling men in Sander’s renowned photo seem solid. But they’ve paused and their gaze is fixed on something in the distance, well out of their way. With the photo’s orientation on the first main room of post-war New Objectivity painting, is it the oncoming march of modernity?

The New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement in German art was named by the art historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub on the occasion of a 1925 exhibition he mounted in Mannheim, featuring contemporary painters such as Max Beckmann, George Grosz, Otto Dix, and George Schrimpf. At the Pompidou, wall tags indicate the 12 or so paintings here that were first presented in Hartlaub’s show, “New Objectivity: German Painting Since Expressionism.” In moving from the murky Meidner self-portrait to a Mannheim standout, Grosz’s Portrait of the Writer Max Herrmann-Neisse (1925), the shift that Hartlaub posited from Expressionism’s interiorized projections on the outside world to New Objectivity’s trust in the signifying force of realist depiction is clear. You observe Herrmann-Neisse’s head bulging with what must be writerly thoughts, while his body is almost wilted from their intensity. With the stark presence of the subject, you’re at pains to identify Grosz in this sachlich (objective) painting.

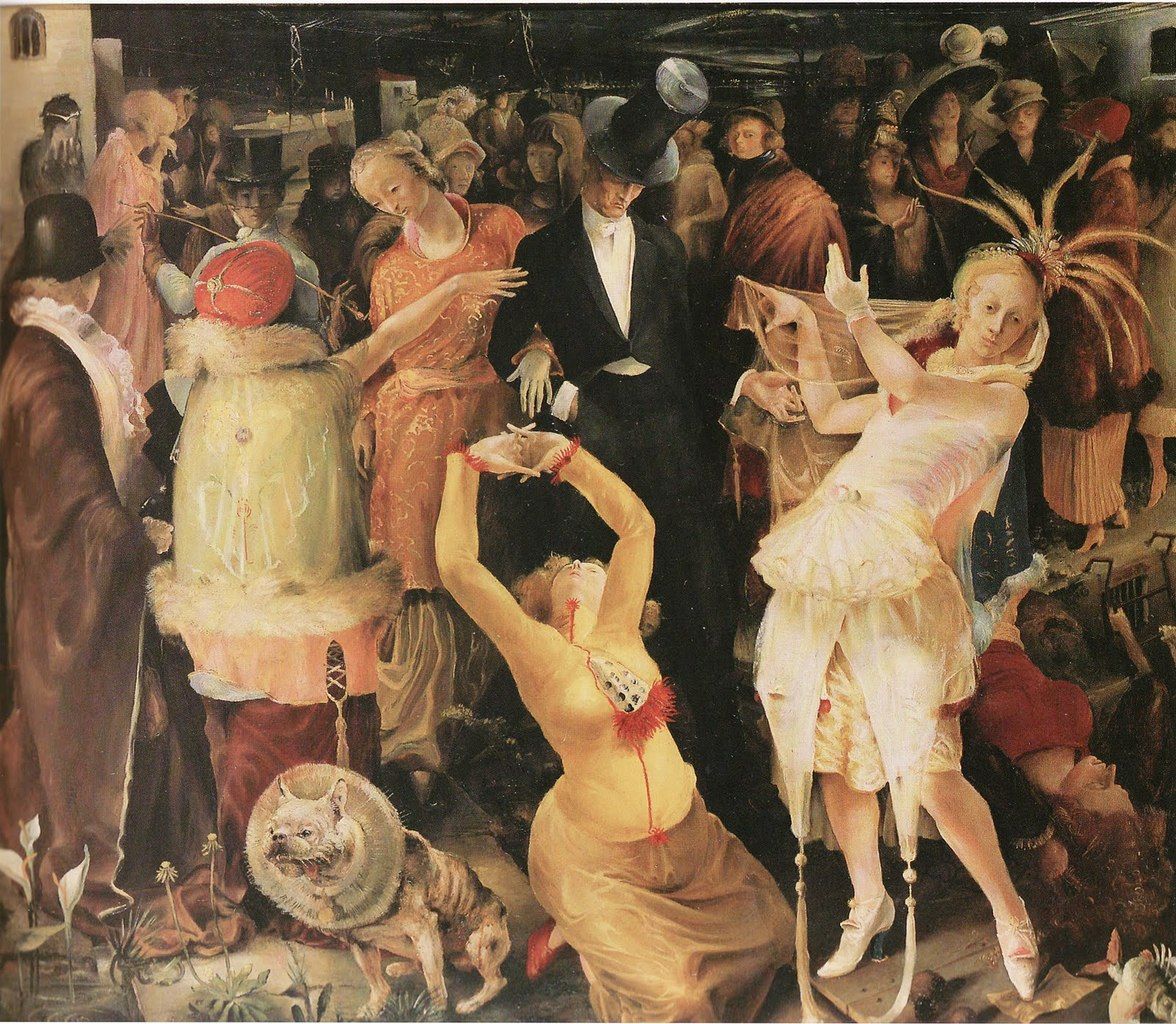

Hartlaub’s show was a hit in the press, so much so the name he chose took on a life of its own as a new shorthand for hip. It seems that by the late 1920s, every cabaret, theater, and boutique owner in the Weimar Republic hoped to have their operation designated sehhhr sachlich (“verrry objective”) by those in the know. Likewise, an expanding wave of artists, illustrators, designers, architects, writers and composers were haphazardly grouped by tastemakers under the New Objectivity label; by 1928, Hartlaub could only try to redefine the term as applicable to any artistic output that engaged the frothy atmosphere of interwar Germany.

Accordingly, the exhibit widens its scope beyond paintings from the artists that Hartlaub assembled (though they are generously peppered throughout the remaining rooms). A series of thematic sections—on standardization, montage, rationality, utility, and more—is a noble attempt to apply some order to the era. But what ultimately comes through are catalyzing contradictions: the cold minimalism of Bauhaus design (seen in furniture, scale models, and ephemera) against the warm crowd scenes of the cabaret; the growing emancipation and representation of the Neue Frau (as in Lotte Lasertein’s portraits, like Russian Girl with a Compact) against the reactive rise of misogynist lustmord (sex murders) with their depiction by major male artists; and the productive conflicts within forms and mediums, as photography and literature strived for the effect of Dadaist collage (see how the novelist Alfred Döblin pasted publicity and newspaper clippings all over the manuscript of his masterpiece Berlin Alexanderplatz) and, in sound, Walter Ruttman surpassed the durational limits of recording technology by turning to synch-sound film roll to make long, imageless audio collages of city life (as in his 1930 piece Week-end).

Hartlaub’s show was a hit in the press, so much so the name he chose took on a life of its own as a new shorthand for hip […] sehhhr sachlich (“verrry objective”)

Rooms and rooms of vital arts and crafts are linked seemingly without end, and the effort to organize them echos the same schematizing intentions of certain Weimar theorists, designers, and architects cited in the show—a desire for order after the horrors of the First World War, soon to be hijacked by Hitler’s rise in the 1930s.

Running as a sort of inner loop to the outer loop described above, a singular focus on the work of photographer August Sander (1876–1964) is another curatorial coup. Centered on what remains of his unfinished project People of the 20th Century, for which he endeavored to take portraits of the various “typologies” of German people from 1910 to about 1939, this section of the exhibit cleverly stands as a literal human core to the intensely varied forms of aesthetic representation surrounding it, all of which took the same populace as its subject.

With his goal of creating a “momentary portrait of the German” (a snapshot in the truest sense), Sander plotted out a complex series of groupings and sub-portfolios like The Woman in Intellectual and Practical Occupations, The Performing Musician, and Farming Types, ultimately printing around 600 photos. The last of these he assembled as The Persecuted and Political Prisoners portfolios from negatives taken by his son Erich before Erich’s death in 1944 at Siegburg Prison, where he was a left-wing political prisoner.

Taken together, Sander’s consistently humanistic photographs have the most staying power in this crowded and cacophonous show. While they indeed make up only a “momentary portrait,” what makes Sander’s project all the more arresting is the moment, before the Weimar Republic’s unraveling and the outbreak of the Second World War: His varied, enigmatic subjects sit as if on a fragile seam joining the long past and our present-day future. By the same token, there is an eerie sense of folly and foreshadowing in his unfinished taxonomy; that is, man’s folly in attempting a comprehensive classification of the world around him (the kind explored generations earlier in Moby-Dick, where the scientific chapters that fall short of a complete cetology mirror Ahab’s doomed quest) alongside the looming machinations of the Nazi party that would soon stratify German society—and Europe—for their own purposes.

In an early room of the show, the 1928 cabaret hit “It’s in the Air” plays from hidden speakers while its lyrics, which charmingly observe a change of atmosphere in Germany (“Things were so different back in the day!”), are posted in large print on a nearby wall; there’s something silly, fiery, thorny, and hypnotic going on, you hear. Today, this overwhelming exhibit still begs the question—what was in the air back then? Maybe trauma, debauchery, or nihilism?

Or perhaps a natural evolution, an outgrowth from the interiority of pre-war Expressionism and the collective release of a people liberated from monarchical rule. The eponymous cabaret-hopping protagonist of Erich Kästner’s zippy 1931 novel Fabian: The Story of a Moralist, a crisp first edition of which dutifully pops up in the exhibit, calls the Europe he’s living in—the Europe of the late 1920s— “a great waiting room” for some impending upheaval: “We live provisionally,” he warns. “The crisis goes on without end!”

The exhibition ends with Reversals, a new room-sized installation by contemporary photographer Arno Gisinger. He projects archival photos of paintings as they were hung in Hartlaub’s groundbreaking 1925 exhibition, and overlays photos of their placement, 8 years later, in the exact same museum when they appeared in the initial Nazi-organized “exhibitions of shame” against so-called Degenerate Art. Indeed, there can be no offsetting the crises that came before and after the comparatively peaceful 1920s on display at the Pompidou. It’s not exactly for art to offset, but, if it succeeds, to exist beyond the fray of historical reaction, whether its own or others’.

And even as crises seem to arrive in an endless parade today, nearly a hundred years later, anyone hoping for a Roaring Twenties redux to follow the pandemic, bouts of authoritarian incompetence, and now rising global inflation is being willfully flippant toward history. Happily, the curators at the Pompidou do not make such a thematic stretch. Instead the many outlets of artistic expression in the exhibit and the way they resist collective categorization emphasize the subjectivity that protects and elevates great art of any era. Alluring, impenetrable, shocking, and monumental, “Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander” hits the same notes as its four-headed, century-old subject.

“Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander”

Centre Pompidou

Place Georges-Pompidou

75004 Paris, France

11 May 2022 – 5 September 2022