Book Review—Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism and the World, by Malcolm Harris

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris

Little, Brown & Company, 2023

$36.00

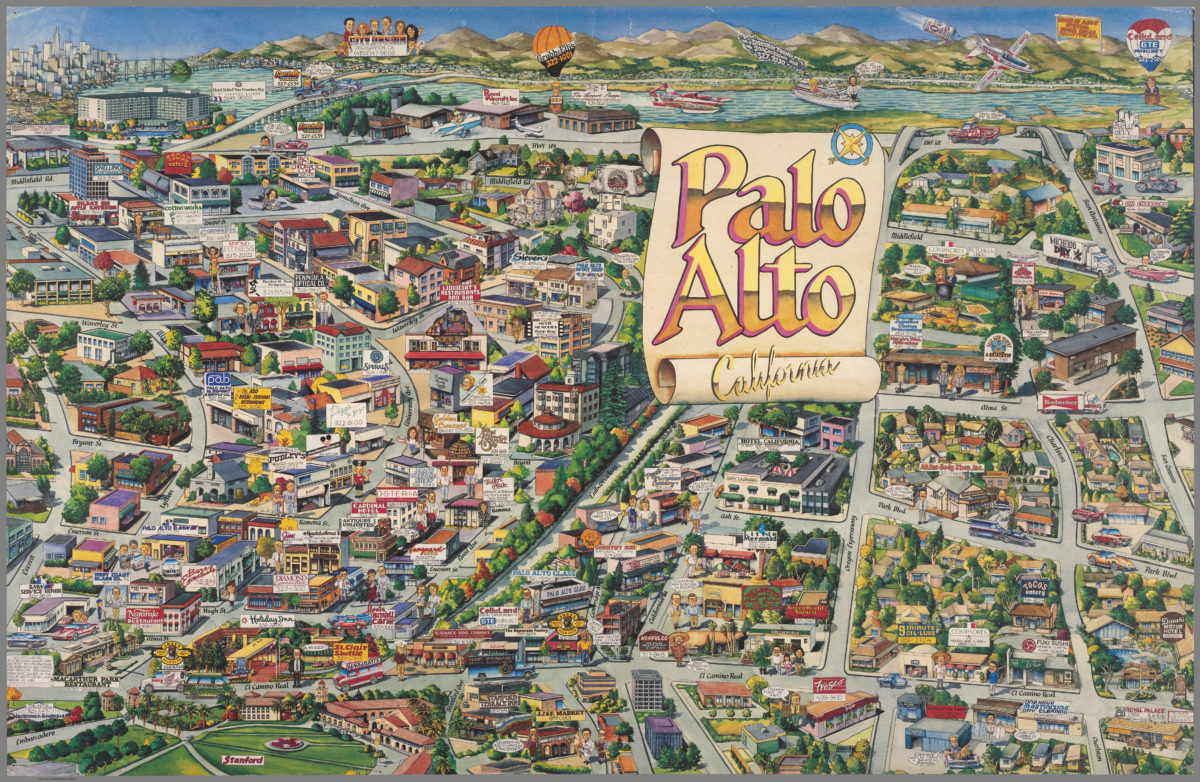

BERATING TECH EXECUTIVES IS BORING. It’s time for a deeper, more holistic and historical critique of the place we’ve learned to call Silicon Valley. Now we have Malcolm Harris’s Palo Alto, which argues that the Valley’s most pernicious tendencies are nothing new. From Harris’s perspective, they reach easily from the age of the gold rush and the genocide of Indigenous people across California, through the rabid anticommunism of Herbert Hoover and the explosion of eugenics, through the development of Cold War terror technologies and the violent oppression of liberation movements worldwide, down to the catastrophically unequal society we live in now.

Palo Alto is not built on new research findings, but Harris has read widely, and he has assembled his tower of public sources to present an unsettling vantage on California, the place where he claims capitalism truly became global. His candid and polemical style is an asset most of the time. If you already share his general outlook, it’s cathartic to watch him rip with gusto into California’s most villainous disruptors. If you don’t, occasional passages of Palo Alto will feel smug or even condescending. In his desire for an all-encompassing Marxist sweep, Harris risks replicating the sort of flippant grand narrativizing that drives so much Silicon Valley rhetoric—a penchant that Stanford literary scholar Adrian Daub examines in his pithy and lucid book What Tech Calls Thinking. But a place as hubris-saturated as California deserves a big and audacious critique to match, and here Palo Alto succeeds at full volume.

The organizing theme of the book—the reason the Santa Clara Valley yields more than just crops—appears when Harris examines railroad baron Leland Stanford. Not long before Leland co-founded Stanford University, he built the Palo Alto Stock Farm and transformed the breeding of racehorses:

Capital’s exigencies dictated that Palo Alto shorten the horse production cycle. That meant training the animals to trot younger rather than letting colts learn to walk before they run. Instead of optimizing for adult speed, they optimized for visible potential… The stock farm’s regimen of capitalist rationality and the exclusive focus on potential and speculative value was called the Palo Alto System and it worked.

Facebook popularized the move-fast-and-break-things philosophy in our time, but Leland Stanford had already laid the track by the end of the 1880s, and his stock farm embodied that philosophy literally. As contemporary horse racing expert Leslie Macleod wrote about Stanford’s treatment of horses, “you must not be surprised if some tendon snaps… Some good material has without a doubt been spoiled.” The Palo Alto System is the drive to optimization, applied to living beings as early and incessantly as possible. Stanford’s ideological successors have extended this approach to everyone and everything in sight. In the spirit of colonialism, they made the leap from optimizing horses to optimizing the entire world.

“[Palo Alto’s] biggest export, more than code, circuit design, and marketing fluff, is human capital,” Harris writes. “Stanford switched from colts to young people, but it was still a breeding and training project.” The model, he concludes, is “progress by victory, defeat, and ruthless elimination, full speed from day one.” His book presents the horrific outcomes of this one-or-zero vision. The earliest include the development of IQ tests and other eugenics-related fads at Stanford University, as well as Stanford alum Herbert Hoover’s wildly successful nourishing of callous corporate cabals. Among the most recent: the rise of a venture capital culture that “made every enterprise into a binary bet,” a workforce intensely bifurcated by class and race, and the winner-take-all ethos that’s dominated Silicon Valley’s schools and driven unusually high youth suicide rates.

But the crux of Harris’s story is found in the postwar: the period when Palo Alto “went straight from rural to something like postindustrial,” when Silicon Valley grew into its namesake and began to dominate the globe. A flood of military funding buoyed Stanford University, and the school helped fill the needs of a country “finished with peace altogether, a nation that has embraced a permanent conflict.” As Harris summarizes the Cold War, “America’s life-or-death race with the Soviets was about which side could assimilate the global South into its circuits of production and consumption.” Companies in Stanford’s orbit led the pack, pioneering corporate offshoring to exploit workers abroad as well as at home. The defense contracting of the 1950s and ‘60s became the war capitalism of the ‘70s and Reaganite ‘80s. Some of the very first laptops in existence, built by a spin-off of Palo Alto-based Xerox PARC, were used by lieutenant colonel Oliver North and his infamous Iran-Contra network.

Early on Harris writes, “What interests me is not so much the personal qualities of the men and women in this history but how capitalism has made use of them. To think about life this way is not to surrender to predetermination; only by understanding how we’re made use of can we start to distinguish our selves from our situations.” Nearly six hundred pages later, he proposes the return of Stanford University’s land and assets to Indigenous stewardship, in particular to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, whose members descend from several Bay Area tribal groups. His vision of Stanford as a center for the “twenty-first-century Indigenous-led movement to protect the biosphere” is moving. It must be emphasized when discussing decolonization, particularly in California, that within the state’s borders are dozens of distinct tribal communities with extremely varied cultures and relationships to place. Specificity is central. And the greater the efforts toward decolonization, the more vital it will be to look beyond the depersonalizing method Harris often uses to understand capitalism’s history.

Palo Alto deserves many readers—not only those who already share Harris’s political views, but also those who remain bewildered that operators like Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel could amass so much power. And it should be a clarifying read for anyone who is affiliated with tech but feels vaguely uneasy about its effects on society. On any given day circa Obama’s second term, I would walk the Stanford campus and see an alarming percentage of undergrads wearing free t-shirts that advertised the war-and-surveillance profiteer Palantir, who at the time were headquartered only a short walk away. If at least a few engineers look askance at their old Palantir swag after picking up a copy of Palo Alto, Harris will have done a public service.