I WAS AT THE KICKOFF RALLY for the first Aldermaston March in 1958—the first march against nuclear weapons in England and the beginning of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. It was the foundational event for left-wing baby boomers in the UK and my own first step into politics. I was 14. I was there by accident, invited along by my surrogate family, the Abramskys, who lived at the bottom of our hill in Highgate, northwest London. The Abramskys were: Chimen, the father, a stout little Russian-Jewish gnome; Miriam, matching but motherly; and my buddy Jack. Chimen and Miriam

were old communists from the East End of London, where my family was also from, and they were the first of a long line of surrogate parents who put up with me during my adolescence. All of my surrogate parents were communists or ex-communists of one kind or another.

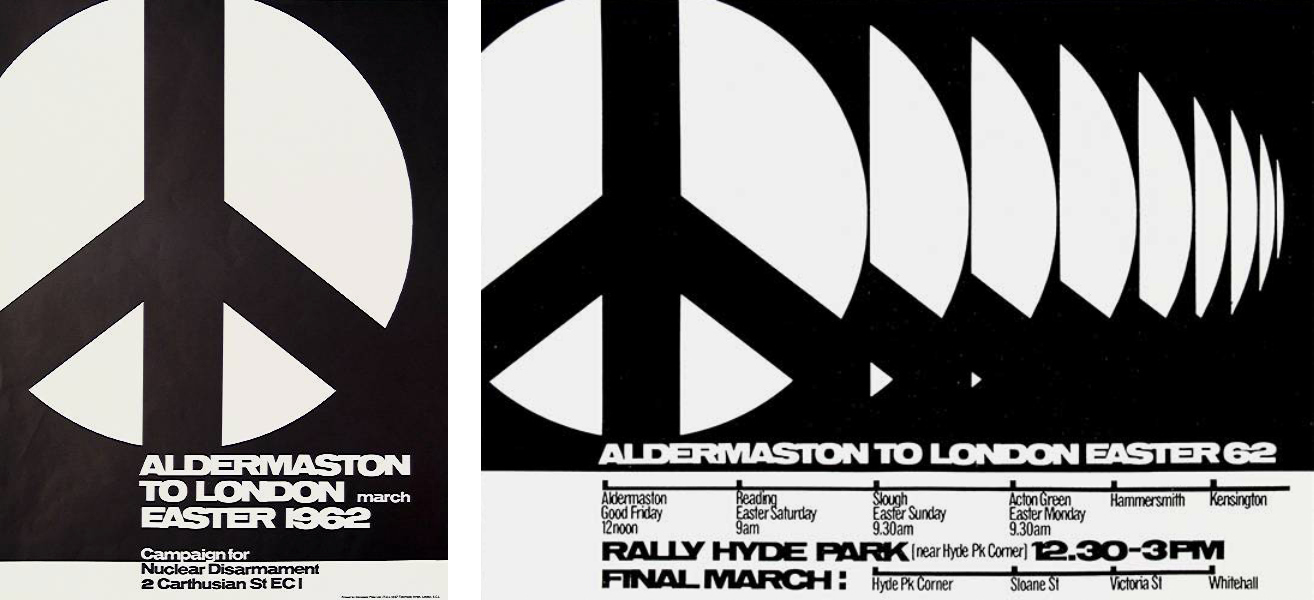

I was just into puberty at the Aldermaston rally and wearing my new duffle coat. I stuck my chest out and proudly displayed it to the marchers as they straggled out of Trafalgar Square to begin the four-day trek to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston.

My mother had gone to Laura Place School in working-class Hackney with Miriam Abramsky and they had rekindled their friendship when my parents moved to Highgate in 1953. My father, prospecting for a house in some place quieter than the huge Edwardian house he’d leased cheaply in Notting Hill Gate during the war, ran into a herd of sheep coming down off Hampstead Heath into Highgate and decided immediately that this was the place for him. It wasn’t the place for my mother. She wanted to be on the other side of the Heath in Hampstead, where the intellectual life of London buzzed and where my parents had lived in the 1930s as students at the London School of Economics. In those days she taught English to glamorous, left-wing German refugees. (One of them was John Heartfield, the photo-collagist. Much later I saw my mother in an entirely new light when I heard her refer to Heartfield as “Johnny.”) Nevertheless, life in our family was organized around protecting my father’s peace of mind—he was the director of the Government Social Survey, a department of the Ministry of Information—and we ended up in Highgate. I spent my teenage years walking up and over the green hump of the Heath to Hampstead, where the action was.

My parents did not come to that first Aldermaston rally in 1958. The official position in the family was that my father’s civil service job meant he had to keep his distance from politics. This wasn’t communicated directly because things weren’t communicated directly in our house, but as CND, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, became the focus of my teenage social life, I noticed that, unlike other parents, my parents never came to CND events. I knew this had something to do with the Communist Party.

I don’t know if my parents were ever actually in the Communist Party. If they were, they were probably long out of it by 1958. My father told me he joined when it looked like the Germans were going to invade England, because he thought the Communists were the only ones who would fight. But later, when I tried to check with James Jefferys, who had been London University Student Organizer for the CP in the ‘30s and was the uncle of my best friend Joe (named after Stalin), James said thoughtfully “Louis? No, no… Winnie, maybe.” I was staggered because I wasn’t accustomed to, or even capable of, thinking of my mother as the dynamic parent. But she was: She was a working-class girl from Hackney who had married up into the professional ranks. She would hate me saying she was working class, though I thought it was a credential, which annoyed her. The words “working class” made her toss her head in irritation, and one time when they came out of my mouth she thumped me on the arm in anger, a rare example of direct communication in our family and the closest she ever came to inflicting pain. I still find it hard to believe she was the one in the CP. But years later, when the MI5 surveillance files on my friend Joe’s aunt Nan drifted up into public view, there my mother was, in Nan’s phone taps, squabbling with the other surveillees over who would get the nice flat overlooking Primrose Hill.

In 1958 my father’s brother Baron was probably still in what, in their branch of the family, they called “The Party.” Baron had been a miner and a CP branch secretary in the Nottinghamshire mines in World War II and then a graphic artist at the Daily Worker, the Communist Party newspaper (we received the Worker when I was a kid, but by 1958 it had disappeared from our doorstep). Nobody quite knew when Baron left the Party. His wife, my aunt Joan, left it around 1956 and my cousin, trying to figure out the mysteries of her family, obtained from her mother the following bizarre quote: “We never talked about those things.” Presumably by the 1960s, when Baron was organizing forecourt promotions for a large gas-station chain and driving around the suburbs in a Bentley, he was out. (He was also on the Nobility List at Fortnum and Mason’s, the classy department store in Piccadilly, because they thought he was The Baron Moss.)

Because Baron had been a miner in the war (his helmet and lamp and his crossed hammer and pickaxe were displayed on the wall of their house in the stockbroker belt south of London), and because he went to meetings with the hard-nosed Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen when the British fascists were acting up, I gave him points over my father. Other uncles on both sides had been in the Air Force but my father was exempted because of his Civil Service job. I thought this was wimpy.

“It’s a good thing your father didn’t have to go in the army,” my Aunt Anne said. “He’d never have been able to kill anyone.”

I had no social life in 1958 because I was at St Paul’s School, far away in Hammersmith, in west central London. I got up every morning, walked down Highgate West Hill to the 214 bus at Parliament Hill Fields and rode it to the Kentish Town underground station. Then I traversed diagonally across London by Northern line and Piccadilly line to Barons Court Station, then trudged past the Sadlers Wells Ballet School and around the St Paul’s playing fields to the school itself. Up on the second floor, in the big studio windows of the Ballet School, the Sadlers Wells students posed angelically. I would catch glimpses of them during rugby practice and think of them as higher beings.

I liked going down into the warm and womblike embrace of the underground, although passengers would occasionally recognize the severe black St Paul’s blazer with its silver badge (and John Colet’s motto: Fide et Literis) and chide me for looking scruffy in public. I liked the underground because it had saved us Londoners in the war—though when I was a babe in arms during the V-1 attacks in 1944 my mother and her sister Molly had refused to go down into the deep Belsize Park station because it was too much trouble. (“What did you do?” I asked. “We got under the table.”) The underground was part of the nostalgic package we children of the ‘40s inherited from the war, along with the bomb sites down the street (two bombs in my childhood block in Notting Hill Gate) and the flowers of rose bay willow herb on the bomb sites and the gray dome of St Paul’s Cathedral rising triumphantly up over the bombed city. “Rubble children,” the Germans say: trümmerkinder. You could see the dome of St Paul’s from my bedroom on the Holly Lodge Estate, half way up Highgate West Hill, where I was experimenting with masturbation. (Here in California, all these years later, I miss the war. I miss that background melancholy that permeated everything in London when I was a child. I still think of myself as a son of the Northern line and I still feel safe in any city with an underground.)

In 1957 I had moved over to the “big school,” the turreted, blackened, Gothic Revival St Paul’s main building, built in 1889 and destroyed a couple of years before John Betjeman made Victorian architecture fashionable. It loomed up over a nervous 13-year-old like Count Dracula’s castle. It was black like all the other public buildings in London. I thought they were supposed to be black. I was amazed when they cleaned up the Natural History museum and it turned out to be built of pale limestone with a delicate blue band along the facade.

Now in 1958, it was the age of Sputnik and at St Paul’s they wanted us to become scientists. Shortly after that first Aldermaston march, I announced I was going to be a nuclear physicist. I didn’t know what a nuclear physicist was and I didn’t connect it with what was happening behind the fence at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston (I was mostly in CND for the social life). My father, who approved of science, brought home the Ministry of Information What-is-Nuclear-Physics? pamphlet for me: I managed to avoid reading it. A few months later, when the Queen came to celebrate the school’s 450th anniversary, we scientists were hidden away in the lab of the junior school physics teacher Tombstone Peters, a stately man with the green-tinged face of a Hammer Films corpse, because we were swots who weren’t civilized enough to be presented to Her Majesty. The school built the regulation private toilet for her visit and painted the first floor of the blackened, gothic main building, the only floor she was going to be exposed to, in pastel colors. These incredible feminine touches, not like anything ever seen at St Paul’s, made us giggle and speculate about her private functions. This was early 1959 and I was still a sniggering little boy. But by the end of the year I had smoked my first joint.

After the eleven plus exam—the exam that sorted you out for life in those days—most of my friends from north London had gone to the local independent school at the bottom of our hill. My friends at St Paul’s were a few swots who lived south of the river, which might as well have been Greenland for me. My social life consisted of occasionally going to Richmond to watch my classmate Ian digest food with his chemistry set, producing a brown sludge. On the way back from Ian’s—a long voyage across London in the top front seat of an empty double decker bus, out above the sodium-illuminated streets like the Flying Dutchman on his bridge—you had to watch out for random thugs looking for middle-class kids to intimidate. This was all part of London life, like playing English v. Germans on the bomb site at the bottom of the hill.

Shortly after First Aldermaston (as one came to call it) my mother figured things out. She put me in contact with a group of kids in northwest London whose parents had organized them into a social group called the “Chums.” The Chum parents were all communists or ex-communists: old LSE friends of my own parents, American refugees from the blacklisting in Hollywood and a group of South Africans, many of them well-padded doctors. Now that I think of it, I realize that it was my mother who was friendly with all the communists. The Chum parents were mostly Jewish. The South Africans lived in the affluent end of Hampstead near Finchley Road, a region I subconsciously identified as too Jewish. I understood Jewish geography. West Hampstead, where my grandmother had a baker’s shop, was marginal, but Golders Green was definitely too Jewish. I didn’t think of myself as Jewish because my self-image came from St Paul’s and schoolboy literature.

“Vus gibt hier?” says a voice, one of the voices of my inner Jew, cultivated much later by experimenting with the Jewish half of my identity in ethnically conscious America. “Vus gibt hier? You thought you were some kind of English Shentleman?”

Well, I did. That was what St Paul’s did for me. I had decided I was going to assimilate. My role models came from Hotspur and Magnet, the antique weeklies that were still going strong 20 years after George Orwell wrote his famous essay on boys’ magazines. I was an aspiring British Gent. I was two thirds of a Public School Twit.

Some time in early 1959 my mother gave in to her Hampstead cravings and signed me up for the Rona Hart School of Ballroom Dancing in Gayton road, off Haverstock Hill, Hampstead’s main street. I walked there on Saturday afternoons, over the Heath then right at the mixed swimming pond on the Hampstead edge of the Heath and through the parking lot where the fair was held on August bank holidays. Then up the hill, past the architect Erno Goldfinger’s house with the sailboat in the window (my parents had modernist leanings and admired the house), then via the old Public Bathhouse to Gayton road, just below Hampstead Village. This was the Walk Past Paul’s House, the Swann’s Way of my youth. My friend Paul, at 40 Parliament Hill Road, had been signed up for the Rona Hart dancing school too but I was cruelly distancing myself from him as the Chums got more important in my life: Your parents weren’t in the CP!

The route by Paul’s house led onwards via Hampstead Village, where the Everyman Cinema was about to become the center of Chum life, to the home of my new surrogate family, the Jaffes. The Jaffes, replacing the Abramskys, were South African Chum parents who had left The Party at the time of Hungary and lived an expansive ex-colonial lifestyle over there by Finchley Road. I pretty much lived there myself on weekends, flirting with Peter Jaffe’s mother and admiring his father’s collection of modern paintings. Was it the expansiveness I liked or just the fact that they seemed to be a happy family? I was trying to get away from something pinched and crazy at home.

Peter Jaffe was at St Paul’s too but his strategy was different from mine. Since I was trying to pass I had signed up for everything, including rugby and the Cadet Corps. Well, everything except the Church of England, the one thing actually required for you to rise to the top. It was well known that a secret society of future rulers took confirmation breakfast together every month; you couldn’t get to be Head Boy if you weren’t one of them. The Cadet Corps was also necessary for success, but in the Cadet Corps at least you got to shoot guns. (This came in handy in California during the Sixties. In 1968 I was the only person in the Stanford SDS who had fired fully-automatic weapons.)

Bravely, Peter Jaffe refused to join the Cadet Corps, marking himself as a Bolshevik, and spent Monday afternoons doing PT with a band of religious objectors and foreigners. I had to spend valuable weekend hours polishing brass and freezing the silicon shine on my boots in the refrigerator. If I was too stunned by a week of rugby, the Cadet Corps, and homework to walk to Rona Hart on Saturday afternoon, I would play on my mother’s guilt about sending me to St Paul’s in the first place and make her drive me around the south side of the Heath to Hampstead. She had a small, square, black Ford, one of the first cars on our street. She drove, my father didn’t. In fact she drove with aggression and finesse, and later she taught me to drive, her idea of teaching being to throw me into the insane central London traffic at Hyde Park Corner. My father’s not driving was a mark of his weirdness. He was from the Kafka generation, the oversensitive sons of successful Jewish businessmen. He’d had huge fights with his own roaring father and now, we were given to understand, he was to be treated gently.

The pubs on the walk past Paul’s house: the Magdala on Parliament Hill, with a bullet hole in the front where Ruth Ellis shot her lover, last woman to be executed in England. The hostile Railway Tavern in South End Green. The Freemasons on Downshire Hill (my mother liked the elegant Victorian houses on Downshire Hill with their filigree iron balconies). The Wells, the Flask (vaguely intellectual), the Cruel Sea (tourist), the White Bear (proletarian) and finally the Holly Bush, a low- ceilinged hobbit hole on Holly Bush Square at the top of the hill. The Holly Bush was the jumping-off point for the publess trek through leafy residential Hampstead to the Jaffes’ house near Finchley Road. I walked from the Holly Bush to the Jaffe’s because the walk was sociable, and also because by closing time I would be too drunk to ride a bicycle.

The White Bear was the first pub that would serve us, beginning in the summer of 1959. It was a no-frills boozer in what was then the working class enclave of New End, above the Public Bath House. It was patronized by thin, stunned, narrow-chested men in flat caps who didn’t seem to mind 15-year old boys (unlike the Railway Tavern, where the clientele was younger and more aggressive). They reminded me of my grandfather in Brighton, an old soldier who had just died of lung cancer (gassed in World War I plus about a million roll-up cigarettes). I knew there was a class gulf between us and the relatives in Brighton; my mother would go down there and come back depressed because they wouldn’t take any money from her. But I went to my grandfather’s funeral wearing my St Paul’s black blazer anyway; I was so pleased with the blazer and its silver badge that I hardly realized he was dead. As at the Aldermaston rally, I was more interested in my clothes than in the event.

At the White Bear, they would serve anybody. Later in 1959 I bought that first joint at the White Bear, from Mick Roach, a thug. Mick was also rumored to have a gun for sale. Although he was a thug he was one of our thugs because he had been at the Aldermaston March—Second Aldermaston by this time and the first time the march came back to London from Aldermaston, ending up with a tremendous crescendo in Trafalgar Square. We, the Chums, were on the march, escaping from home with our sleeping bags and rucksacks. Mick sold me a standard North London joint, carefully hand-assembled with mostly tobacco, a little hashish shaved in and a filter neatly inserted in the end. (My grandfather, who favored Rizla Red papers and Old Holborn tobacco, used a rolling machine.) The price of that first joint was two shillings, same as a pint of beer, and, of course, it had no effect. We talked casually about the Aldermaston March—or at least I was trying to be casual. Mick wondered if X had done it to Mary Jane Smithers with a right hand screw or a left hand screw that night on the march. He demonstrated and I flinched internally; I had tried to get it on with Mary Jane myself but she had asked “Are you a virgin?” and my confidence had collapsed. Of course I was a virgin.

At the Rona Hart School of Dancing I tensely held on to an equally tense fat girl while keeping my feet in the footprints of the foxtrot diagram in my head. I was too embarrassed to ditch her. Besides, the long-legged Hampstead girls were too classy for me. I knew I was the wrong sort of person at Rona Hart. Perhaps, I told myself, it was because we lived in desperately unhip Highgate; anyhow, I couldn’t see how to rise in the ranks. Fortunately, right about then, right about the moment I met the Chums, rock and roll kicked in. Paul bought two 78s, the first rock and roll records I ever saw: Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Great Balls of Fire” and the Big Bopper singing “Chantilly Lace.” I see, as in a dream, us ballroom-dancing students, magically transformed, waltzing anarchically up Haverstock Hill like the boys escaping from school in Jean Vigo’s Zero de Conduite, to merge with the Chums at the El Serrano coffee bar in Hampstead Village. “Peggy Sue” is on the jukebox:

Ah love yew, Peggy Sue,

With a love that’s pure and true.

Oh Peggy,

Mah Peggy Sue-oo-oo…

Bullfight posters! Chianti bottles with wicker sleeves! Ratatouille! Just up the road at the Everyman, Zero de Conduite is actually showing. Suddenly we are teenagers.