Preliminary Note: Prior to the publication of this Special Section, our CAP Co-director Amy Sims sadly passed away on 2 March 2023. Her contribution to this Special Section constitutes her final published thoughts. This Special Section is dedicated to her memory.

IN THE FAERY LANDS FORLORN

an introduction by Josef Chytry & Amy R. Sims

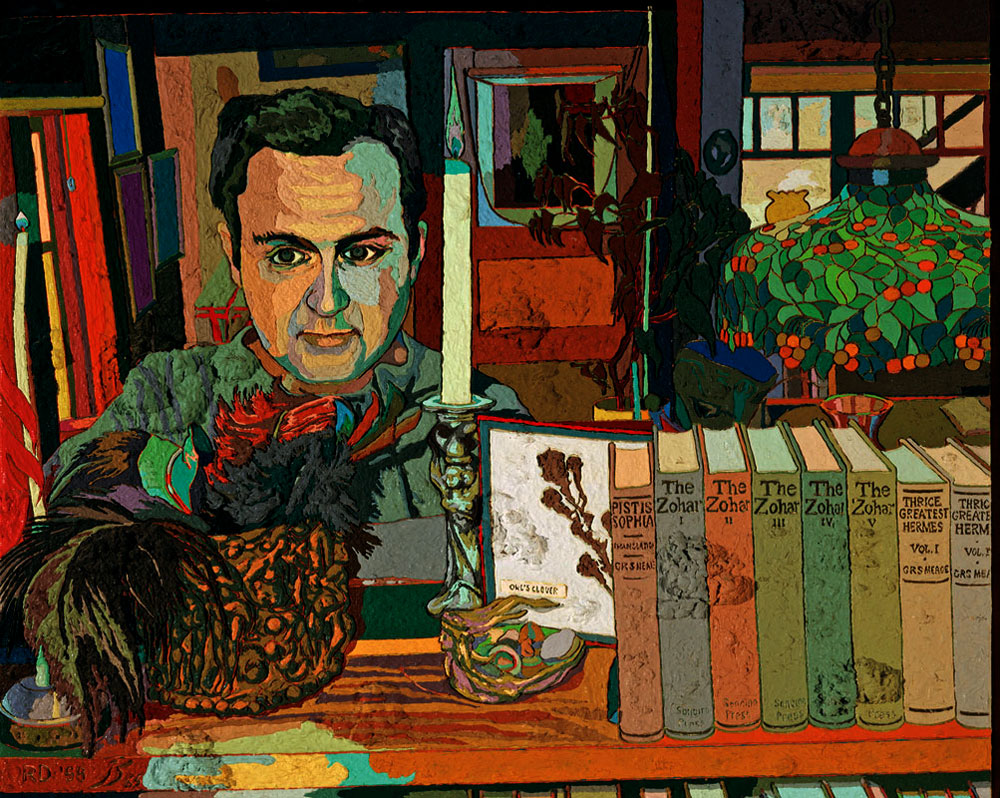

Launched in 2021 at the California College of the Arts, San Francisco, in robust rivalry with the world pandemic, our Centre for Aesthetics and Politics (CAP) hovers—like Sufi Ibn Arabi’s “fedeli d’amore”—in a perpetual state of “perplexment.” Perplexed by ambiguities within Frankfurt School Critical Theorist Walter Benjamin’s case against “aestheticization of politics” (Ästhetisierung der Politik) that he extracted from Fascism’s signal cunning to fascinate the masses with show, display, ornament while firming their chains of subordination to autocratic governance. Ambiguous because instead of wholesale denial of the entire apparatus of such possible exploitations of art and the aesthetic, Benjamin championed instead— whatever it might portend a cabalistic Marxist of Benjamin’s vintage— the “politicization of art” (Politisierung der Kunst).

Upon this airless confrontation of apparent opposites, post-World War II thought has rushed in to scatter its bevy of neologisms: “paraesthetics,” “aesthetic politics,” “aesthetic statism,” “aesthetic community,” even “kallipolis.” Perhaps the least tilted terms come from Michel Foucault when in his positive readings on behalf of a contemporary “aesthetics of existence” he has cheered on the “politico-aesthetic choice” for our contemporary ethical life.

Like most substantive movements of spirit the “aesthetic-political” carries its rousing origin. Confronted by the challenges of the French Revolution while appreciating its underlying republican motivations, German poet-philosopher Friedrich Schiller in 1794 rang out the aesthetic-political clarion call: “If one is ever to solve the problem of politics in practice he will have to approach it through the aesthetic, because it is beauty by which man makes his way to freedom.”

Strong words. Backed by considerable competence in Kantian aesthetics and poetic practice, Schiller fired up legions of European thinkers, poets and “free spirits” to carry through the vaster implications of his proposal over the next century, widening the goals of societal and political change to bring in such presumably creative dimensions as spontaneity, dance, performance, even Play. Yet vulnerable at the same time to the usual gamut of doubt, skepticism, and liberal caution uncomfortable with the positive tonalities to Schiller’s theory and rhetoric.

Perhaps with at least occasional good reason. Heading off our Special Section on aesthetics and politics in the postwar era, Martin Jay calls on the postwar aesthetics of the Frankfurt School’s prime “negative theorist” Theodor W. Adorno to bolster the case against directly politically redemptive resonances behind the works of artists by showing how Adorno’s sponsorship of idiosyncrasy for art, as against sublimation, successfully cuts off any promising cooperation between art and the political. For her part, Amy Sims thoughtfully explores politics and art in the context of revolution. Revolutionary leaders have recognized that the arts can be a powerful language in helping the disaffected visualize the possibility of transforming their “reality,” and have equally understood art as a social power capable of binding diverse social groups together into a common vision. They have used and abused the arts as an inspiration for change and as a force for control. Looking specifically at the process by which Mao Zedong’s call for a new, truly Chinese proletarian art in the postwar period degenerated during his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966 into the simple propaganda of a political power grab, readers are invited to ponder the difference between art in service to a creative vision, and art as simply propaganda.

In qualified contrast Robert Pirro draws from Hannah Arendt’s postwar political philosophizing the benign inference, leavened by the lasting standard of the classical Greek polis, of an aesthetic judgment capable of formulating promising forms of democratic individuality and community. Acknowledging the intense political oppositions and violences of the late 1960s and 1970s while struck by the redemptive power of pop-rock musical creations during that same period, Peter Murphy explores some of the key factors that musically counter the dystopian tendencies in contemporary politics and allow for recognition of an “instinctive classicism” transcending “decadal vortices and critical divisions.”

Our final contributions push the buttons of radical interpretation in significantly different rhetorical registers. Thomas Haakenson’s fervid endorsement of the effect of the postwar Black Arts Movement (BAM) stemming from Oakland, California to decolonize European monopoly over concepts of revolutionary artistic practices not only takes on central moments in that effort, but raises critical questions of what the concept of an artistic avant-garde might entail when widened beyond its historical European articulations. Conversely lowering tonalities, Lydia Degarrod imaginatively knits together poetic expression, historical narrative, and poignant imagery to evoke mourning over the ramifications of the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima for a family whose home it had once been, as she touches on the fragility of “dwelling in this world.” Discursively calling upon the resources of the poetical, Degarrod’s essay itself becomes poetry—a fitting resonance to close out our Special Section.

That our contributors offer such disparate perspectives and positions to the proper relationship of art and politics need not surprise. Perhaps then the safest option that our maiden Special Section finally suggests is to adopt Foucault’s recommending the criterion of agonism as: “less of a face-to-face confrontation than a permanent provocation.”

THE IDIOSYNCRASIES OF ARTISTS & THE ART OF POLITICS

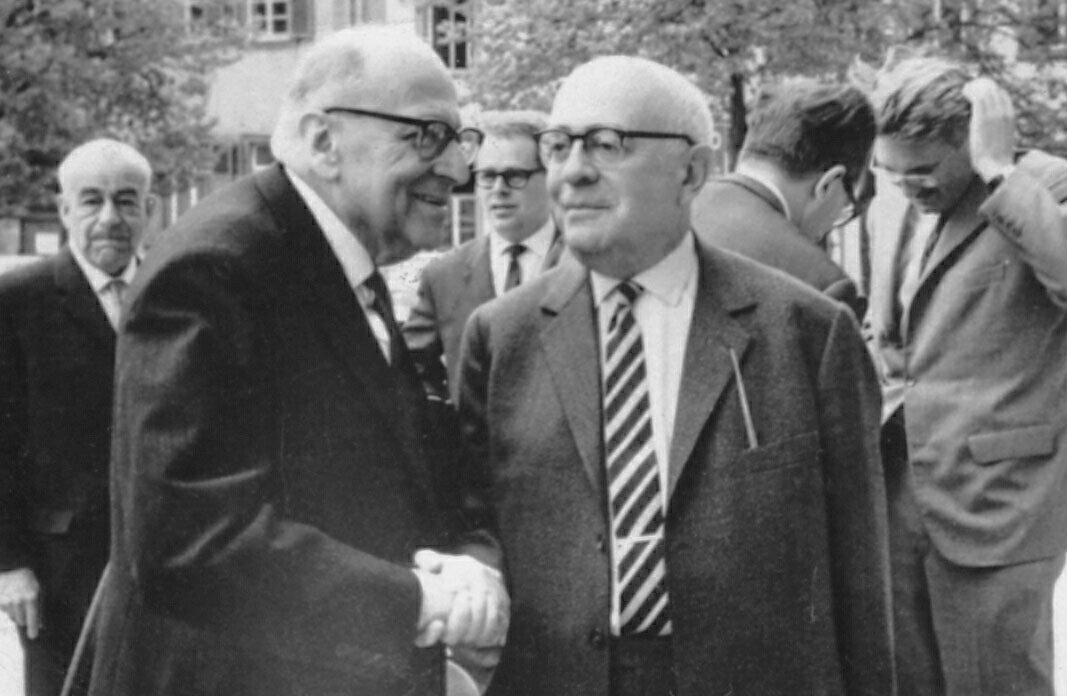

Theodor Adorno (R) with Max Horkheimer (L), April 1964. Photograph by Jeremy J. Shapiro

“Artists do not sublimate,” Theodor W. Adorno, a leading member of the Frankfurt School, asserted in Minima Moralia, the collection of aphorisms he wrote in California during the postwar years and published in 1951. The idea “that they neither satisfy nor repress their desires, but translate them into socially desirable achievements, their works, is a psychoanalytic illusion… Their lot is rather a hysterically excessive lack of inhibition over every conceivable fear; narcissism taken to its paranoiac limit. To anything sublimated they oppose idiosyncrasies.”

Among the many inferences that can be drawn from this provocative statement, the one that previously drew my attention concerned the limits of Adorno’s acceptance of psychoanalytic theory. Despite his general blessing of the arranged “marriage of Freud and Marx” sought by the Frankfurt School, when it came to aesthetic creativity, he balked at the reduction of works of art to the transfigured psychological fantasies of their creators. For to do so would both spiritualize the unfulfilled needs of the desiring body and turn works of art into affirmative consolations for the actual denial of those needs. It would also disregard the integrity of works of art as more than the projected daydreams of artists, and thus rob them of the ability to challenge the status quo through their formal qualities and material non-identity with the constitutive subject.

As it happened, there was a place for sublimation in Adorno’s understanding of art, albeit not of transfigured libidinal desires. He claimed instead that artworks sublimate suffering rather than desire, and that the posterior aestheticizations of prior devotional or cult objects could be seen as sublimations of the original mimetic impulses indirectly preserved in them. But what I want to address now is something entirely different: the implications for the relationship between art and politics in his ancillary claim that what artists really do is oppose their idiosyncrasies to sublimation. Valorizing idiosyncrasy was, in fact, a frequent gesture in Adorno’s work, and has been recognized as well in the work of other Frankfurt School figures. Walter Benjamin, a heterodox member of the School, has been praised for his “aesthetics of idiosyncrasy,” and Axel Honneth, the leading member of the School’s third generation, argued for “Idiosyncrasy as a Tool of Knowledge.”

As the literary critic Jan Plug warns in an insightful discussion of the role played by “idiosyncrasy” in the Frankfurt School’s analysis of anti-Semitism, treating it as a positive concept is futile, even impossible, for once it becomes a generic category, it performatively contradicts what it substantively seeks to promote: the need to subvert abstract conceptualizations. “And yet,” he writes, “this impossibility remains an absolute necessity for any possibility of liberating societies from anti-Semitism.” It marks “the limits of conceptuality. Thus it posits an irrecuperable outside, in fact the idiosyncratic as that very outside. The idiosyncratic, then, demands its conceptualization (destined to ‘failure’ as it is) in order to posit itself as such, as idiosyncratic to that very theorizing.” Idiosyncrasy, in fact, functions in Adorno’s “negative dialectics” as a synonym for “non-identity” and “non-conceptuality.” Resisting the logic of subsumption, fungibility and commodification, it apophatically gestures to what it cannot positively signify without contradicting itself performatively.

In their analysis of anti-Semitism in Dialectic of Enlightenment, Adorno and his colleague Max Horkheimer interpret hatred of the Jews as a primary example of the intolerance of idiosyncrasy, the pressure to eradicate the non-identical in the name of totalizing identity, understood in communal, national and racial terms. Freedom from anti-Semitism is thus entangled with the even more ambitious task of undoing the damages of identitarian totalization in whatever form it may appear. Among its manifestations, they argue, is the ideal of a fully integrated, balanced, autonomous subject, which is able to master the unruly demands of nature both within and without.

The Jews, to the extent that they have resisted the possessive individualism of bourgeois culture and retained a trace of the 15 mimetic comportment that the instrumentalization of reason sought

to snuff out, can be said to embody a particularity that is not limited

by propriety. That is, they have escaped being caught in the trap of the entirely immanent subjectivity posited as a normative ideal in Western thought ever since Descartes by never fully assimilating to the dominant norms of the cultures in which they find themselves. To quote Plug once again, “understood in this way, not only as a simple resemblance or adaptation but as the mechanism by which these are achieved, idiosyncratic mimesis denotes the moment at which the subject is no longer, or not yet, a subject. It marks, at the very least, the body’s escape from intentionality, the body’s freedom and independence from subjectivity.”

This is not the place to evaluate Horkheimer and Adorno’s characterization of the Jews or their explanation of the sources of anti- Semitism. Whether or not they escape the trap of positing yet another version of the “the figural Jew,” to borrow Sarah Hammerschlag’s term for metaphoric interpretations that homogenize the disparate realities of actually existing Jews, is not something we can adjudicate now. What is more important for our purposes is to note their claim that the idiosyncratic qualities of the Jews, so often denounced by their enemies, reflect a kind of non-intentional adaptation that never turns into a perfect duplication of what is resembled mimetically. For what this stubborn refusal to jettison idiosyncrasy in the service of subjective integration helps us to understand is the logic behind Adorno’s rejection of Freud’s theory of sublimation to explain artistic creativity. That is, when he links that creativity with hysteria, paranoia, the overcoming of inhibitions and extreme narcissism, he is arguing that the artist—like the unassimilated Jew—should never be understood as a balanced, self-possessed subject able to transfigure his unruly desires in the service of cultural transcendence. Although Adorno and Horkheimer do not address the Zionist alternative that sought to integrate Jews into a society and polity of their own making, the logic of their argument is that it too would entail a loss of that idiosyncratic resistance to sublimation they so highly valued.

Casting doubt on the actual existence of such an integrated subject, not to mention positing it as a normative ideal, of course, became commonplace in late twentieth-century theory, even in the psychoanalysis of Lacan and others. Whether or not this implies that all of us are inherently no less idiosyncratic than Adorno’s artists and that those who claim to possess integrated, sublimating subjectivities are actually ideologically deluded (remaining in Lacanian terms at the mirror stage rather than taking on the full implications of entering into the symbolic) is difficult to say. What is more certain, it seems to me, are the implications that can be drawn for the relationship between art and politics.

The Frankfurt School always argued that marginality might provide a critical vantage point on the status quo. In his essay on “Idiosyncrasy as a Tool of Knowledge,” Honneth continues this tradition: “The disposition social criticism requires is the hypertrophic, the idiosyncratic view of those who see in the beloved everyday of the institutional order the abyss of failed sociality, in routinized differences of opinion the outlines of collective delusion.” He adds that idiosyncratic social criticism requires the help of theory to challenge the assumptions underlying conventional wisdom and the naturalization of historically variable givens. In this sense, it complements the rejection of culturally affirming sublimation that Adorno attributes to idiosyncratic artistic creativity.

But how, we must ask, does idiosyncrasy serve to enable the political action that can lift us out of the “abyss of failed sociality” that is the deeper truth underlying the ideological “beloved everyday of the institutional order?” Although artistic creation, like theoretically informed social criticism, may ultimately inspire action in the political realm, neither, after all, is directly equivalent to transformative political praxis itself. Nor can praxis be reduced to “applied” theory or the literal realization of aesthetic imagination, as if it were simply following a recipe to cook a meal. Despite the glib slogan that “everything is political,” it is important to avoid reducing everything to a night in which all cows are black.

In his essay on “Idiosyncrasies: Of Anti-Semitism,” Jan Plug attempts to address this issue by invoking the distinction, originated by Carl Schmitt and popularized by a number of European theorists in the 1980’s, between die Politik and das Politische, la politique and le politique, and la politica and il politico. The first term of each pair is normally translated into English as “politics,” while the second, based on the portentous translation of an adjective into a noun, has become “the political.” Whereas the former implies the messy, mundane realm of electoral contests, coalition-building, legislation, policy-making, and transactional compromises, the latter suggests a purer, even ontological rather than ontic realm where the agonistic struggle for power is an end in itself. Referring to the way in which the dominance of the centered, coherent, autonomous subject is undermined by the unsublatable impulses of the body expressed by idiosyncratic behavior, Plug argues that:

It leaves open the space, the very space of a radical mind/body split, that refigures the political space as other than the site of labor or “political” action as it is customarily conceived. This is the space of the political, the opening without which political action in this narrower sense could never be thought, the space of the political as the resistance to the logic that allows for the subsumption of body to mind, for subsumption tout court.

If we replace “subsumption” with “sublation,” both of which contain and domesticate the expression of idiosyncratic, corporeal impulses, we can see the way in which Adorno’s dictum about artistic creativity may suggest an affinity between art and a certain ontological notion of “the political.” In both, the autonomous, centered subject is denigrated in favor of the impersonal, often erratic forces that disrupt settled order and challenge reified categories, opening a “space” for something radically new to appear. Rather than a takeover of one by the other—either the “aestheticization of politics” or the “politicization of art” famously posited by Benjamin as a fateful choice—each is valued for sharing a common potential for liberating transgression.

But is the putative commensurability of art and “the political,” we have to wonder, really sufficient? If “idiosyncrasy” is understood to be an “impossible” concept, always gesturing to its “outside,” how does it comport with what at least in Schmitt’s usage was defined precisely as “the concept of the political?” Can one, moreover, pass so easily from the everyday world of mundane “politics as usual”, with all of its tawdry compromises and disappointing imperfections, to a purer, more essential alternative that, like artistic creation, opens a space for idiosyncratic freedom from constraint, institutional as well as conceptual? However laudable heroic resistance to subsumption and sublimation may be, it is hard to imagine it serving as the basis for viable action in the everyday world of die Politik, la politique or la politica. If we identify the latter with what Hannah Arendt famously called “acting in concert” or more narrowly in terms of the “deliberative democracy” based on rational discussion advocated by Jürgen Habermas, it may well be necessary to valorize the intersubjective ability to achieve consensus through persuasion or even the transactional skills of compromise. These may well involve a certain culturally acceptable sublimation of libidinal and other demands of the body, including ones that express aggressive feelings. The results are likely to frustrate hopes of opening a new political space for radical change. But can we, at a time when Donald Trump has shown us all too clearly what a de-sublimated politics looks like, be so confident that it will automatically have more emancipatory effects?

Much more can be said about all of these issues. But what seems clear in conclusion is that if Adorno is right about artistic creation’s reliance on idiosyncratic resistance to sublimation and the expression of “narcissism taken to its paranoiac limit,” it is not surprising that a perennial tension exists between art and politics. Or at least it does so when the latter is understood in its imperfect quotidian form rather than as the idealized notion of “the political.” Although a passage from one to the other may be fashioned, it is never smooth or without intractable contradictions. Poets, pace Shelley, are not really the “unacknowledged legislators of the world,” nor should we expect them to be. Despite the yearnings of those from Friedrich Schiller on who dream of a harmonious conflation of the two, the idea of an “aesthetic state” may well therefore remain an oxymoronic impossibility. And thankfully so.

Martin Jay, University of California, Berkeley

THE POWER OF ART IN MAO’S REVOLUTION

ca. 1972, Artist unknown

Why are revolutionary leaders intent on the control of culture, especially art and artists, as a vital aspect of their revolution? Mao’s discontinuity from using art to help create a communist society to weaponizing art in his power struggle to establish totalitarian control during the Great Proletarian Revolution raises several questions including: Where is the line between art in service to a cause and art as propaganda?

Revolutionary leaders suppose themselves to be engaged in creating a better future, and believe that “reality” is malleable, something that can be demolished and reconstructed. They clear the way for this destruction and rebuilding by promoting a sense of boundless possibility or what historian Robert Darnton calls “possibilism” which they offer in contrast to widespread discontent with existing conditions. As revolutionaries, they try to frame reality by articulating existing problems, specifying the next steps that need to be taken, and using forms of visual culture (as a powerful form of communication), to weave together a common goal capable of binding diverse societal groups. In his article “Nomos and Narrative,” law professor Robert Cover explains that in any given society there is a nomos or a vision of an ideal social order that laws are expected to create. And behind every nomos is a narrative clarifying how the creators of that society envision the ideal they want to build, a vision to inspire people and explain why they should do what is expected of them.

Chairman Mao Zedong wanted to create such a nomos (with art as a crucial aspect of it) to advance the cause of his revolution in China. He believed that art is a social power, that artists are transmitters of cultural values, and that art can help prepare the ideological groundwork for creating a new national will and a new vision of people to inhabit a new, utopian Communist community. Mao repudiated a traditional view (as expressed by Thomas Mann and many others) that art is the ultimate form of independent creativity, eternal, concerned with beauty, and demanding unhindered expression. As Goethe had put it, a good work of art can have moral consequences, but to demand moral or political intentions from artists is to ruin their work. Mao, on the other hand, saw art as an instrument of control, a way of first persuading, and later intimidating the Chinese public. He had no doubt that art served ideology.

Unlike another 20th century revolutionary dictator, Adolf Hitler, whose passion for the visual arts was intense, Mao had no deep interest in music, painting, sculpture or architecture. He did have some interest in poetry, calligraphy, and western ballroom dancing (primarily with underage teenage girls), but he did not consider himself an artist of any sort; his interest in art was pragmatic. While hunkered down in Yan’an at the conclusion of his Long March, and confident of the ultimate success of his revolution, Mao articulated his expectations for Chinese artists. In a series of lectures in 1942 and published the following year as Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art, Mao declared that there is no such thing as art for art’s sake and that all literature and art belong to definite classes and are geared to specific political aims. Artists must form a “cultural army” to ensure that “literature and art fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part, that they operate as powerful weapons for uniting and educating the people, for attacking and destroying the enemy, and for helping the people fight the enemy with one heart and one mind.”

Pointing out that 90% of the population of China were workers, soldiers, and peasants, he argued that art should be geared expressly for them because they are the class that leads the revolution. But the problem facing workers, soldiers, and peasants, according to Mao, was that they were illiterate and uneducated as a result of many years of rule by the feudal and bourgeois classes. Consequently, they were eagerly demanding education and works of art that were easily understandable, that would strengthen their enthusiasm for struggle, and that would build their confidence in victory against the enemy. Artists must therefore shift their allegiance away from petty bourgeois reactionaries and move to the side of the people through the process of studying Marxism-Leninism. Only in that way, Mao asserted, will China develop a truly proletarian art—an art that creates characters out of the real life of people suffering from cold, hunger, and oppression, and that helps the masses to propel history forward.

After Mao’s proclamation in Tiananmen Square of The People’s Republic of China in 1949, he could actually accomplish his goal of creating a new visual culture for a new China, art that was accessible, no longer just for the wealthy elite but for all the people. Socialist realism was introduced in the 1950s by Chinese artists who had been sent to Russia to be trained in oil painting, while Soviet artists such as the famed Konstantin Maksimov came to the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing to train Chinese artists in Russian style realism. Paintings in this new style were reproduced as posters and widely distributed to factories and workplaces so that this new visual culture could permeate everyday life. Previously, almost all the important teachers at Chinese Art academies had studied overseas in Europe or Japan and the Chinese Art schools structured their curricula to resemble those of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris or the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Now under Mao, however, Socialist style oil painting was promoted as a replacement for the centuries- old Chinese art of ink painting which was seen as too elitist and as the product of the rotten old society that needed to be replaced.

All Chinese Art academies established Communist Party committees that had top level decision-making power in all matters. New courses such as the political history of the Chinese Communist party, and dialectical materialism, became a required part of the curriculum. Political campaigns were used by the CCP as a means to attack and purge those with different viewpoints. One early example was the “Purge Counterrevolutionary Elements” campaign (1950) during which students were expected to spend entire days facing the designated counterrevolutionary targets and denouncing them instead of attending classes. Also newly required for both students and teachers was the obligation to “enter deeply into life” by spending some weeks or months each year in farming villages or factories to collect material for depicting “real people” in their creative works. Of this time, Zheng Shengtian (a 1958 graduate of, and then professor at, the Zhejiang Art Academy) later wrote (as co-curator of the New York 2008 exhibition “The Art of China’s Revolution”) that for young people like himself, it was a dynamic and idealistic time. The Communist vision of a harmonious, classless society appealed to him and his fellow students, and the idea of creating a new art was something that resonated with their idealistic aspirations. Art was placed in service to an ideology in which they believed.

Art and all aspects of Chinese culture changed when Mao launched his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966— ostensibly to prevent China from deserting the revolutionary Marxist-Leninist path, but in actuality a pure and simple power grab by Mao having nothing to do with sustaining communist principles. In the aftermath of Mao’s failed second Five Year Plan, “The Great Leap Forward” (1958-1963) during which 45 million people were disastrously killed in the worst man-made famine in history, Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping and Vice Chairman of the CCP Liu Shaoqi advocated more moderate and practical policies (that were highly successful). When Nikita Khrushchev denounced his predecessor, Stalin, first in his “secret speech” at the closed 1956 Soviet Party Congress, then repeated publicly at the open 1961 session, and began a process of de-Stalinization, Mao became paranoid that he would meet the same fate as Stalin.

Under the pretext of preventing “reactionary bourgeois revisionists” from undermining Communism, Mao launched the Great Proletarian Cultural revolution as an instrument to remove power from the CCP in order to reassert absolute loyalty and power to himself. The two intertwined elements of the revolution were creating a cult of Mao and emphasizing class struggle to ferret out class enemies (some of whom were his closest comrades). China had been governed for more than 2000 years by an emperor who was revered as both leader of the country and its spiritual authority. Mao appropriated this tradition, appearing “godlike” by remaining remote and mysterious while expecting others to implement his goals, and “revered political leader” by promoting hatred of class enemies as “capitalist roaders, ox devils and snake demons” who would certainly drag China back to the bad old days of the Kuomintang were it not for Mao’s leadership. Art was weaponized to play a role in both facets.

To enable his Cultural Revolution, in May 1966 Mao set up a powerful new body, the Cultural Revolution Group (CRG) which had direct control over culture and which consisted of strong Mao loyalists: Jiang Qing (his wife), Chen Boda (his personal secretary), Kang Shen (his intelligence chief) and Zhang Chunqiao (writer and propagandist). He also worked with Defense Minister Lin Biao to promote the cult of Mao in the People’s Liberation Army. The Cultural Revolution began later that month when faculty at Beijing University created the first big wall poster (dazibao) criticizing university administrators for trying to suppress the impending revolution. Immediately hundreds of such character posters sprang up all over the university and at other schools. Schools and universities suspended classes but mandated that students remain on campus to engage in revolutionary activities. Art magazines and art journals stopped publication to encourage art students to engage in creating posters and lead “struggle sessions” and denunciations. Groups of armed Red Guards (teenagers, typically the children of high communist officials who were self-appointed revolutionaries and were granted Mao’s “warm and fiery support”) searched homes and studios, smashed antiques, pianos, violins, and records, tore up paintings, toppled statues, and raided museums, palaces, temples, ancient tombs, pagodas, and tea houses. Mao had also instructed that grass, flowers, and pets were bourgeois habits and were eliminated by the Red Guards.

Authors Jung Chang and Gao Yuan, former Red Guards, gave detailed accounts in their books (Wild Swans and Born Red) of the epidemic of scapegoating and widespread random violence that swept China during the Cultural Revolution. Professors and artists, along with communist officials, were the most frequent targets—they were beaten, sometimes fatally, forced to kneel on broken glass, have ink poured on their heads and faces (to turn them black, the designated color of the class of landlords and counter-revolutionaries), forced to remain for hours in the painful “jet plane” position (pushed to one’s knees, arms twisted and pushed up behind the back as if to dislocate them), confined in cowsheds and other “prisons” where they were tortured, had their heads shaved in yin-yang patterns, and paraded through the streets with dunce caps on their heads and slogans written all over their bodies. Many artists, forced to witness their work being destroyed, committed suicide. Famous traditional artists such as ink painters Lin Fengmian, Li Keran, and Pan Tianshou are examples of those who were denounced as class enemies and badly treated because of their age and level of expertise.

The Red Guards vowed to “launch a bloody war against anyone who dares to resist the Cultural Revolution, who dares to oppose Chairman Mao,” and enthusiastically carried out Mao’s command to destroy the “four olds”—old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits of the exploiting classes. The expectation of enemy figures had been planted in the population, and it was necessary to find and destroy them. For the Red Guards, a proper revolutionary was aggressive and cruel to class enemies; any form of humane consideration was considered bourgeois. Every morning or evening, the Red Guards made “a report to Mao” by gathering in front of his portrait, waving his Little Red Book above their heads, and wishing him an infinitely long life.

Artists participated in creating the cult of Mao by displaying their approved works in art exhibitions. In February 1967 more than 20 Beijing colleges provided art works for the exhibition at the Beijing Observatory, “Smash the Lui Shaoqi-Deng Xiaoping Counterrevolutionary Line.” The exhibition began with a quotation from Mao and the first work displayed was a portrait of Mao waving his hand in a gesture that symbolized his leadership in launching the Cultural Revolution. A brief sample of exhibitions held thereafter is: “Long Live the Victory of Mao Zedong Thought” (National Art Museum); “Long Live the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” (Tiananmen Square) which had more than 16,000 works on display; and “Long Live the Victory of Chairman Mao’s Revolutionary Line” (National Art Museum). These exhibitions then traveled to factories, communes, and army units.

“The Red Sea” (hong haiyang) was an artist’s movement to create and spread Mao’s image everywhere (including schools, farms, factories, villages, offices, and newspapers) and turned Mao into the main subject of the art of the Cultural Revolution. Red Guards in the Central Academy of Fine Arts published a small booklet in 1967 that consisted of 54 woodcuts of Mao and it became the most important source for portraits of Mao. The most influential and the most frequently copied of all Mao images during the Cultural Revolution was a woodcut by Shen Yaoyi, “Chairman Mao Waves, We Move Forward” which depicts Mao’s first meeting with Red Guards at Tiananmen Gate in 1966. Many other influential images of Mao during this period came from Shan Yaoyi’s woodblocks and were present everywhere: The surface of nearly every public space in China was covered with portraits of Mao along with his quotations, no one could dare to discard old newspapers for fear of being labeled counter-revolutionary because every front page had a picture of Mao and every few lines of print were quotations from Mao. Propaganda posters became the most widespread form of visual art, most of them reproductions of paintings from the major exhibitions. One of the most famous paintings was Tang Xiaohe’s “Strive Forward With Wind and Tides,” depicting an energetic Mao waving after he completed his famous swim in the Yangzi River. Although Mao actually swam with his bodyguards, in the painting he is surrounded by Red Guards, workers, and soldiers. The point was to depict Mao’s vigor and suitability for leadership, and his close connection to the fervor of the Red Guards. As Kuiyi Shen has written for the “Art and China’s Revolution” exhibition, one of the hallmarks of the Cultural Revolution was that all art was propaganda.

Following the death of Mao in 1976, the Cultural Revolution ended with the arrest of the CRG, including Mao’s wife Jiang Qing. Former Red Guards Jung Chang and Gao Yun quoted people they encountered during the revolution: “What revolution? Do you call what you are doing revolution? It’s beating, smashing, and looting” (Gao); and “there is nothing cultural about it! There is only brutality” (Jung Chang). Departing from his initial vision of using art to destroy the old to establish the new, Mao destroyed much of China’s cultural heritage without constructing anything new, and he weaponized art as a helpful means to do so. There is indeed a difference between art in service to a cause and totalitarian control of art as propaganda.

Amy R. Sims, California College of the Arts

HANNAH ARENDT: DEFINING THE POSTWAR AESTHETIC POLITICALLY RATHER THAN GEOPOLITICALLY

In locating the postwar era between the years 1945 and 1991, convention has defined that period as one primarily structured by the ideological struggle between two globally-active nuclear powers who manage to compete politically, economically, and militarily for almost a half century without destroying one another or humanity. That world of bipolar rivalry and contention between the United States and the Soviet Union, which began after the final defeat of Nazi Germany facilitated the parting of these strange bedfellows and ended when one of them gave up the ghost, left its mark on major developments of postwar American society and politics, including the rise of the national security state, saber rattling nuclear confrontations, costly political and military interventions across the world, and the space race. A postwar seen through the perspective of Hannah Arendt’s thought would not be defined by the drama of superpower rivalry but by a drama of human agency bounded by world historical developments demonstrating how concerted action could extinguish individual freedom, at the start of the period, and, at its end, promote individual freedom’s fullest political expression.

Arendt’s career as an American political theorist began in the mid-1940s as she endeavored to understand in real time Nazi Germany’s unprecedented continent-wide campaign to exterminate European Jews. In important respects, that career had its posthumous culmination more than forty years later with the peaceful self- mobilization of ordinary citizens against Communist authoritarian regimes across Central and Eastern Europe, a development whose fullest significance Arendt’s works of the 1950s and 1960s prepared us to see. In aiming to teach her readers and listeners to recognize the existential significance of politics, Arendt developed an aesthetically-attuned form of political reflection fundamentally different in its premises and approach from the realist, liberal and Marxist scholarship of her day.

While Arendt never formulated her thought under the rubric of “aesthetic politics,” the distinctiveness of her political theory can be understood by appreciating its concern with both the aesthetic dimensions of politics and the political dimensions of aesthetics. Deeply informed by a youthful immersion in ancient Greek poetry and inspiring personal exposure to the philhellenic ruminations of Martin Heidegger on the disclosive aspects of “Being,” Arendt came to see politics as an activity whose existential significance was crucially dependent on the presence and response of actor- spectators relating to each other and to a world modified by their interactions. Guided in part by Immanuel Kant’s modeling of the faculty of judgment, she sought to emphasize what we might call the political dimensions of aesthetics by calling attention to how spectatorship of, and involvement in, public affairs served to invite plurally-situated actor-spectators to share and compare judgments of political events and developments. In general, her unique approach to understanding politics and its significance for human life enables us to define the postwar, one might say, aesthetic-politically rather than geo-politically.

Arendt’s fullest appreciation of the aesthetic dimensions of politics or the disclosive effects of political spectatorship was preceded and importantly shaped by her confronting the radical scope of Nazi Germany’s attack on European Jewry. While reports of Nazi massacres of Jews began to appear in American news columns in 1942 and were urgently discussed in the intellectual and social networks of New York City in which the newly arrived refugee Arendt came to participate, what would become known as the Holocaust did not become front page news in the United States until after elements of Patton’s Sixth Armored Division stumbled upon the concentration camp at Buchenwald in April 1945 and Eisenhower arranged for a group of influential journalists and editors to tour the deadly facilities at Buchenwald, Dachau, and Bergen-Belsen. Once Arendt set to work on understanding what had happened to European Jewry during the war, she was faced with a fundamental problem: how to understand the Nazi fixation on exterminating every single Jew in Europe, from infants to the oldest seniors, even when the pursuit of this continent- spanning mass murder project undermined Nazi military efforts. To her mind, this phenomenon was so unprecedented in its apparent irrationality that it resisted conventional modes of understanding and common sense. “The incredibility of the horrors is closely bound up with their economic uselessness. The Nazis carried this uselessness to the point of open anti-utility when in the midst of war, despite the shortage of building material and rolling stock, they set up enormous, costly extermination factories and transported millions of people back and forth.” Her response to this challenge was to engage in “an historical investigation that employs imagination consciously as an important tool of cognition.”

In her first major American work of political theory, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), Arendt located the radical novelty of Nazi evil in the regime’s establishment of an institution—the Nazi concentration and extermination camp system—which defied all precedents. “The camps are meant not only to exterminate people and degrade human beings, but also to serve the ghastly experiment of eliminating, under scientifically controlled conditions, spontaneity itself as an expression of human behavior and of transforming the human personality into a mere thing.” With the concentration camp’s establishment of an environment of “absolute terror,” Arendt suggests that we had passed an existential threshold; culturally educated Europeans, living in a highly differentiated society with a complex division of labor, and employing the highest levels of technical proficiency, had organized a form of collective life aimed at eliminating human spontaneity and making individual human beings absolutely superfluous.

One indicator in Arendt’s breakthrough book of her appreciation of the radical challenge posed to existing modes of understanding, whether in the form of conventional political analysis or traditional categories of political philosophy or even popular common sense, was her adoption of narrative techniques lending themselves more to literature and the arts than to the behavioralist modes of analyzing large scale patterns of behavior then coming into vogue in academic social science. She drew upon the fictive worlds of novelists to call attention to the circulation of racist and imperialist ideas in Europe later picked up by totalitarian ideologies. She also employed narrative devices such as oxymoron and moral hyperbole to evoke the denaturing cruelty of the camp system. In addition, she evoked the history of Western art (“medieval pictures of Hell”), tropes of Expressionist film (“gruesome crimes in a phantom world”), and devices of Gothic narrative (“an evil spirit gone mad”), to muster a sense of the unprecedented and disorienting horror of the conditions and effects of the concentration and extermination camps.

In theoretically confronting the experience of totalitarian domination in these unconventional ways, Arendt’s work of the 1940s and early 1950s called for a political response attentive to how radical attacks on human individuality and solidarity in Europe undermined prevailing categories of understanding in the West. Her assessment of the epistemological challenge raised by the advent of totalitarian mass murder would eventually find expression in thought-provoking recommendations to acknowledge the loss of “the Ariadne thread of tradition,” to confront “the abyss of freedom,” and to “think without a banister.” In these theoretical moves, she anticipated the later emergence in postwar American academia of intellectual movements (among whose avatars were Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Richard Rorty) which challenged the foundationalist premises of American philosophy, political and social theory, and the humanities, more generally. Eventually turning in her work to notions of aesthetic judgment as a way of conceptualizing viable forms of democratic individuality and community—“it is as though taste decides not only how the world is to look, but also who belongs in it”—Arendt can also be seen to anticipate postmodernism’s robust influence in the fields of aesthetics and cultural theory.

Of course, Arendt, who died in 1975, did not have the opportunity to engage with the arrivals of postmodernism and deconstructionism on American shores. And, anyway, her theoretical interests remained focused on the status of, and prospects for, pluralistic and meaningful political agency in the aftermath of Nazism’s catastrophically murderous rule. Mapping out the Western tradition’s ordering of human activities in The Human Condition (1958), she moved on to excavate the founding moments of the American republic in On Revolution (1963) for insight into how a politics of voluntary concerted action carried out by strongly individuated citizens might be reinvigorated and disseminated in the modern world. Her discovery in that latter book of a lost tradition of revolutionary agency signaled a homecoming of sorts, whereby she connected the revolutionary actions of late colonial British North Americans with the activities of political councils and clubs spontaneously formed during European revolutions from 1789 onward. This theoretical work enabled her later to recognize and mostly welcome the popular mobilizations of the 1960s, whether for civil rights or against the war in Vietnam, as yet another discovery by everyday people of the joys of “public happiness,” that when a person “takes part in public life he opens up for himself a dimension of human experience that otherwise remains closed to him and that in some way constitutes a part of complete happiness.”

No less significant in her book on the American revolution was her choice to conclude it with an extended quotation, in ancient Greek script no less, of choral verse and dialogue from Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus at Colonus. This return to the Greek poetry which she had loved from the time of her youth hinted at the never fully realized aesthetic- political basis of her theoretical affirmation of living a life of public action and commitment: the ancient Greek civic institution of tragic theater. To be sure, her many, scattered references to the characters, plot lines, and language of Greek tragedy and its successors and to the various theorizations of the political significance of that performative and literary tradition were never developed into a systematic theory of the politics of tragedy. Perhaps she was too mindful of the possibility that German intellectuals’ long standing attentiveness to tragedy and tragic forms of thought may have facilitated German citizens’ moral collapse and abdication of political responsibility under the Nazis. In seeming recognition of this danger, she chose her words carefully in her wartime and early postwar essays and preferred such terms as “catastrophe,” “annihilation,” or “destruction” to “tragedy” when referring to the consequences of Nazi rule. Yet, toward the close of the 1950s and throughout the 1960s, Arendt’s theorization of a participatory vision of politics, in which political action and relationships unfolded in a public space between plurally-situated citizens, was accompanied by proliferating references to elements of Greek tragedy, its modern successors and to the traditions of criticism inspired by them. These references enrich our understanding of Arendt’s formulation of the “space of appearance,” “where everything that appears in public can be seen and heard by everybody and has the widest possible publicity.”

Arendt analogized the space of appearance manifested by concerted action to the tragic theater in several ways. In places, she reworks Aristotelian concepts related to Greek tragedy, including catharsis, pathos, and drama, to emphasize the profound emotional rewards promised when one engaged in free political action with one’s peers. In other places, she mentions tragic characters or cites tragic verse to suggest the lasting dignity of even failed attempts at concerted action in order to hold out historically-fleeting episodes of citizen activism as both a consolation for great political disappointments and as an inspiration for future attempts at exercising political freedom. In the background of all of these evocations of the politics of tragedy was the exemplary role played by Greek tragedy in fostering the emotional self-possession, civic solidarity, and political education of citizens of ancient Athenian demokratia.

Had she lived long enough, Arendt would have appreciated how the 1989-1990 collapse of Soviet-style Communism in the face of increasing popular mobilization vindicated the answer Sophocles’ Theseus gave to the pessimistic wisdom of the tragic chorus of Oedipus at Colonus, “Not to be born prevails over all meaning uttered in words.” His answer, that “it was the polis, the space of men’s free deeds and living words, which could endow life with splendor,” serving as it did as a coda to her 1963 book on revolution, would have served her equally well in explaining the willingness of hundreds of thousands of ordinary citizens to engage in political action and risk arrest, injury, or worse as participants in Solidarity and Citizens’ Committees in Poland, the Committee for Historical Justice in Hungary, the church peace prayers held in East Germany, the Civic Forum in Czechoslovakia, as well as the Roundtable discussions, negotiations, meetings and marches across all of these countries. In them, Arendt would have seen resonant expressions of the popular genius for political self-mobilization and self-organization whose historical remnants she had traced in the revolutionary tradition.

With the world-transforming emergence of those councils, she, who had faulted the American founders for failing to provide the revolutionary spirit with a lasting institution, would have also anticipated what was to happen in the aftermath of the revolutions of 1989-90. The robust forums of public protest, discussion, and discussion, which had been formed by the mostly spontaneous action of so many ordinary citizens in Central and Eastern European countries and which had led to the dissolution of longstanding authoritarian regimes, were replaced by parliamentary democracies, one of whose primary interests lay in narrowing citizens’ political agency to the act of voting in periodic elections. Living as we do in an era when the transactional spirit of representative politics has facilitated ever deepening levels of corruption among political elites and an ever spreading sense of alienation among citizens, we could do worse than to revisit Arendt’s salutary vision of a public realm of free citizens actively engaged in shaping their common life.

Robert Pirro, Georgia Southern University

FRACTURED POLITICS AND POP-ROCK CLASSICISM

Politics divide while music unites. This is a truism that also happens to be true. Take the case of the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was an era of intense political divisions. Mass protests, vociferous polemics, and political violence were common. Yet the soundtrack to the era was filled with gorgeous harmonies and infectious rhythms that became, in time, a widely-shared culture. Its legacy is one of the few bits of common culture today that transcends political and moral divisions. 1965 to 1975 was an exceptional time of musical creation. A rich vein of pop-rock music rose to the surface. Like all golden ages, this one was short-lived yet its influence continues to reverberate decades later.

If you observe politics for long enough you begin to realize that it is decadal in nature. In my life-time we have segued through the anti-communist 1950s, the anti-war 1960s, the militant 1970s, the free-market 1980s, the information age 1990s, the terror-inflected 2000s and the populist 2010s. For sure there are continuities in politics. But those more often than not are continuities of division. We disagree and we repeat ad nauseam those disagreements. We are like mice on a spinning wheel. Debates between left and right, liberals and conservatives, centrists and socialists, institutionalists and activists recur. Round and round we go, without necessarily resolving very much.

Even when we seem to agree, we disagree. The anti-communist liberal of the early 1960s and the illiberal progressive of the 2010s are very different creatures. Likewise the classic liberal free-market conservative differs sharply from the national-populist conservative or the illiberal social conservative. Neo-conservatives and libertarian conservatives clash bitterly over the wisdom of war as do anti-war leftists and national-security liberals. To a large extent politics is a function of judgment. It establishes lines for or against, pro and anti. Every judgment creates a distinction and each distinction sub- divides into ever-more minute distinctions. In fact it is division all the way down. Music is different. With each political faction and sub-faction armed with its own furious critical judgment, no one can tolerate sitting in the same seminar room with anyone else. Yet you can still find these squabbling individuals at a concert enjoying the same music.

Since Immanuel Kant, philosophers have often argued that aesthetic preferences are a matter of taste. In other words, these preferences lack universal validity. To an extent, this is true. Whether you like the Beatles or Led Zeppelin (or neither) is a matter of taste. Listeners sometimes defend their tastes quite aggressively. As do cultural critics. At times both behave like political partisans. The recurring problem experienced by everyone is not judgment as such but rather tunnel-vision judgment. The faculty of judgment is the way we carve up the world analytically. We separate one part from another. However separation lends itself to fixations and monomanias.

Fortunately though our judgments are qualified by our intuitions. No amount of critical music analysis for example can overcome the brain’s immediate intuitive recognition of ingenious chord progressions, diverting ways of getting to a tonal center, or mischievously seductive rhythmic patterns. Immediate judgments, whether they are musical or political, are also qualified by the judgment of time. As time passes the influence of fads and fashions dissipates. A tacit but ruthless sorting process takes place.

In the case of music, the residue left behind is a broadly consensual catalog of works of enduring value that has survived the greatest aesthetic test of all: Is a work still worth listening to after fifty years? The simple fact is that a remarkable number of records of the pop-rock golden age have passed this test. Compare that number with pop-rock artifacts from the 1980s, 1990s, 2000s and 2010s. Each successive decade has produced comparatively fewer works of lasting value, works that bear repeated listening over time and that transcend their own immediate era of creation.

What is it about golden-era works that gave them such staying power? Part of the answer is the generic power of music. Music taps into the synthetic part of the brain. Harmony, melody and rhythm in their different ways create the types of abstract unions of opposites that appeal deeply to the pattern-recognition right-hemisphere of the brain. Music unifies because it stimulates, in the right hemisphere, patterns that we find very satisfying. Whereas politics and criticism tend to be left-brained and analytical. They separate, divide and dissect. In politics we argue; in music we harmonize.

The most interesting music embodies a paradox. It offers familiarity combined with strangeness. It draws us in with something we recognize as familiar. Then it takes us to surprising aural places. 1960s and ‘70s pop-rock excelled in doing this. It contained a lot of ingenious chord, melodic, and rhythmic patterns, brain teasers and ear-worms that made us want to listen to something again and again. The art of this was to take a surface layer of familiar sound elements and then twist and turn these in surprising ways. The key is to simultaneously fulfill and defy listener expectations.

Artists and composers use innumerable techniques to combine the familiar and the strange. Among these are modes, breaks and ambivalent tunings; the flattening, sharpening, sliding or bending of notes; counter melodies, rhythmic shifts, polyrhythms; distortion, dissonance and muting; combinations of static and moving lines; quirky phrasing and fills; shifts between chord tones and tension-inducing extensions; feedback and chordal note suspensions; chord inversions, phrase endings, swells, fades, tension notes, and octave jumps.

The golden age of pop-rock offered an additional intriguing kind of synthesis. This was genre synthesis. It took a huge range of pre-existing popular genres and the occasional classical or archaic genre—and merged these. Imagine a multitude of liberal and conservative political genres being fused. Unimaginable? Well, yes, in the sense that politics is predominantly analytic not synthetic. Music is the opposite. It harbors a natural impulse to synthesize. This happened to a remarkable degree in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The original creative musical fusionism of the golden era drew on rock-n-roll, rockabilly, folk, blues, jazz, gospel, soul, funk, R&B, Brill Building pop, and country genres. Diverse currents converged in singular visions.

Epitomizing this were Bob Dylan’s amalgam of epic surrealism, sardonic folk, garage rock, lovelorn pop, Memphis and Chicago blues, psychedelic country and New Orleans’ brass band on Blonde on Blonde (1966) and the Beatles’ White Album (1968) with its amalgam of musique concrète, music hall, country pastiche, ska, parodic blues, orchestral lullaby, heavy metal, and Beach Boys styles. The incantation, stream-of-consciousness, jazz, chamber orchestration, blues and Celtic folk of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks (1968) and the country-folk, epic drama, apocalyptic-folk, plaintive ballads and muscular rock of Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush (1972) display similar artful fusions. Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti (1975) segued between brutal hard rock and delicate acoustic folk, blues swagger, metallic-gospel, pop, boogie, keyboard prog, cinematic orchestral epic, lilting country-pop and ribald funk-metal. What makes these works stand out is not just their stylistic breadth but the way that each stylistic allusion is melded into an instantly recognizable whole.

Creation appears in many forms. Brilliance can emerge from the ingenious application of musical techniques. Joni Mitchell’s use of unorthodox guitar tunings and her exploration of tonal possibilities on the album Blue (1971) and the Bacharach-David-Dionne Warwick combination’s use of complex chords and asymmetrical melodies for their ‘66-71 pop singles are prime examples of this. Other artists can be credited with the early development of a distinctive music genre. Ray Charles is a key figure in the evolution of soul music in the 1950s. Similarly the Maytals pioneered late-‘60s reggae and Marc Bolan ‘70s glam music.

But something supersedes all of these. This is the inventive artist who assimilates multiple genres. What makes the ‘65-75 era exemplary is the repeated incidence of these uncanny syntheses— among them Elton John’s Tumbleweed Connection (1970), The Who’s Who’s Next (1971), Genesis’ Foxtrot (1972), David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust (1972), the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main St. (1972), and Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run (1975).

All creativity ebbs with the passage of time. That is true of both collective and individual creativity. Golden eras wane. So it was with the gilded pop-rock era. Typically, creative personalities are very productive. All the major figures of the golden era continued to produce music on a large scale. On occasions they would manage to reach the creative heights of their iconic period. However the mind is not indefinitely elastic. Repeated stretching ends in a loss of elasticity. That’s the Achilles heel of the creative personality. Greatness is fleeting.

While the golden era had an unusually high percentage of gifted fusionists with their impeccable talent for unexpected genre combinations, each decade since has had their own tally of fusionist works. Among them The Clash’s punk-pop-soul-R&B-ska-reggae- rockabilly-jazz laced London Calling (1979), Elvis Costello and the Attractions’ Imperial Bedroom (1982) blend of baroque pop, torch song and wall-of-sound, and Prince’s Purple Rain’s (1984) mix of rock, electronica, and R&B. Later on there’s Suede’s 1994 glam-rock, baroque-pop, art-rock, cinematic, and orchestral Dog Man Star (1994) followed by the vast looping collage of alt-rock, wall-of-sound, grunge, orchestration, heavy metal and art rock on The Smashing Pumpkins’ Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995), and Radiohead’s dense blend of electronica, sampling, alt-rock, atonality, cinematic ambience, jazz-funk-psyche-rock fusion and musique concrète on OK Computer (1997).

Notably though, each decade since the golden era has produced proportionately fewer classic works. An aesthetic classic is a work that transcends its own time. A golden era produces a lot of such works. When they first appear they are transformative. Yet they prove durable. In contrast, with the passing decades pop-rock music has continued to proliferate genres, most with short-lived moments of intense popularity: baroque pop, mod, power pop, psychedelic pop, punk, reggae, new wave, art pop, heavy metal, heartland rock, blue eyed soul, electronica, hip-hop, ambient, disco, trip-hop, alt-country, alt-rock, industrial, indie-folk, dance pop, standards, Latin, Celtic, alt-rock, dream pop, Britpop, jangle pop, K-pop, garage, dance punk, and more. With new genres come new production styles which also tend to date badly. Few production styles transcend their own time.

Fusionism is open to a wide range of genre styles but it also has the musical challenge of integrating eclectic music forms into a compelling unity. The act of creation has to be able to make divergent genres converge. If the artists who do this successfully were simply eclectic in their behavior, then their work would be idiosyncratic. Albums would be little more than a random menu of an artist’s personal tastes rather than a synthetic unity. Artists who have a real talent for fusionism are rare.

A lot of politics is like a lot of second-tier and third-tier pop-rock music. It is ubiquitous in its time but also trapped by that time. In every decade the tenor of politics changes. Yet, like musical genres or production styles, the debates and divides of each decade are transient. To a large degree political ideas are over-determined by shifting psychological moods. Political actors adapt to this. They appear in public behind a wide variety of evanescent rhetorical masks. They adopt transient public personas.

Past decades have seen many well-rehearsed mask styles including those of the patrician, Machiavellian, boss, patron, confessor, idealist, amiable dunce, avuncular helper, hyper-partisan, and so on. The most recent decade, the 2010s, saw a remarkable rise of personas based on types of personality disorder. These included narcissistic, paranoid, anti-social, a-social, magical-thinking, impulsive, histrionic, avoidant, dependent and obsessive-compulsive types. The entire political spectrum from left to right was tainted by these bizarre personas. In step with this, the 2010s was the weakest decade ever of pop-rock classicism. The essential breadth of imagination evaporated from music and politics simultaneously.

It is interesting to observe the changing psychological styles of politics. Decennial forms of analysis (the ‘60s, the ‘90s, etc.) yield insights. Yet what is commonly missing from these analytic diagnoses is an understanding of the synthetic dimension of mind and society. In its seventy years of existence, pop-rock music has produced decennial innovations that the ear is analytically attuned to and responsive to (sometimes positively, sometimes negatively) along with a much smaller number of works and creators that transcend the powerful decennial demarcations.

Culture critics and political partisans alike are drawn to decennial waves like moths to light. They find them irresistible. One day we have ‘60s-prog; next day ‘70s-punk is king. That’s how culture and politics work. The shifts occur rapidly. One day the Republican Party is dominated by Bush institutionalists; the next day by Trump populists. For years Clinton centrists controlled the Democratic Party; then mercurially it was Obama-era progressives. This is not new. Shakespeare’s history plays are full of such political swing-shifts.

The styles of decennial politics are reminiscent of the decadal turn-over of pop-rock music genres. Genres have a pattern of rising rapidly to ubiquity and then quickly fading. The singer-songwriter in the 1970s; disco in the late ‘70s; grunge in the 1990s illustrate this. Genres don’t die. They enter a (now) vast musical pool that can be drawn on at will. Past genres offer semantic units that creators use as scaffolding for their works. Politics is similar. It operates with ubiquitous decadal styles that rise and fall. These styles are distinctive mixes of psychology, policy and performance just as music genres are distinctive mixes of harmony, melody and rhythm.

Music genres tap our analytic faculties. ‘80s disco and new wave pop genres were distinctive compared with ’70s blues rock or ’60s chanteuse pop. Successive generations as they come of age have a desire to demarcate themselves from those who have come before. Just as sixties folk-rock fans parsed themselves from the cool jazz, rockabilly and rock-n-roll styles of the 1950s.

As the wheel of music turns so too does politics. Analytically distinctive mixes of personality, psychology, and performance rise and fall swiftly. They appear all-consuming until they abruptly disappear from sight. Occasionally though a figure with a synthetic rather than analytic style of politics will emerge. Winston Churchill, the genre-transcending liberal-conservative, is a brilliant example of this. Such personalities, however, are the exception not the rule.

The exceptions, though, are important. Analyzing and judging are key functions of the human mind. These are inescapable and necessary. However they are also inherently limited. A world filled with criticism and bereft of harmony is dystopian. In politics this dystopia is remarkably seductive. The incessant creation of political styles, like musical genres, draws us in. These styles though quickly run out of puff. Their ubiquity lacks durability. As with music, what ultimately matters is that, from time to time, we come across a small number of political figures whose instinctive classicism allows them to transcend decadal vortices and critical divisions. These are rare souls who are crafted for all seasons.

Peter Murphy, La Trobe University & Cairns Institute, James Cook University

THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT IN THE POSTWAR ERA

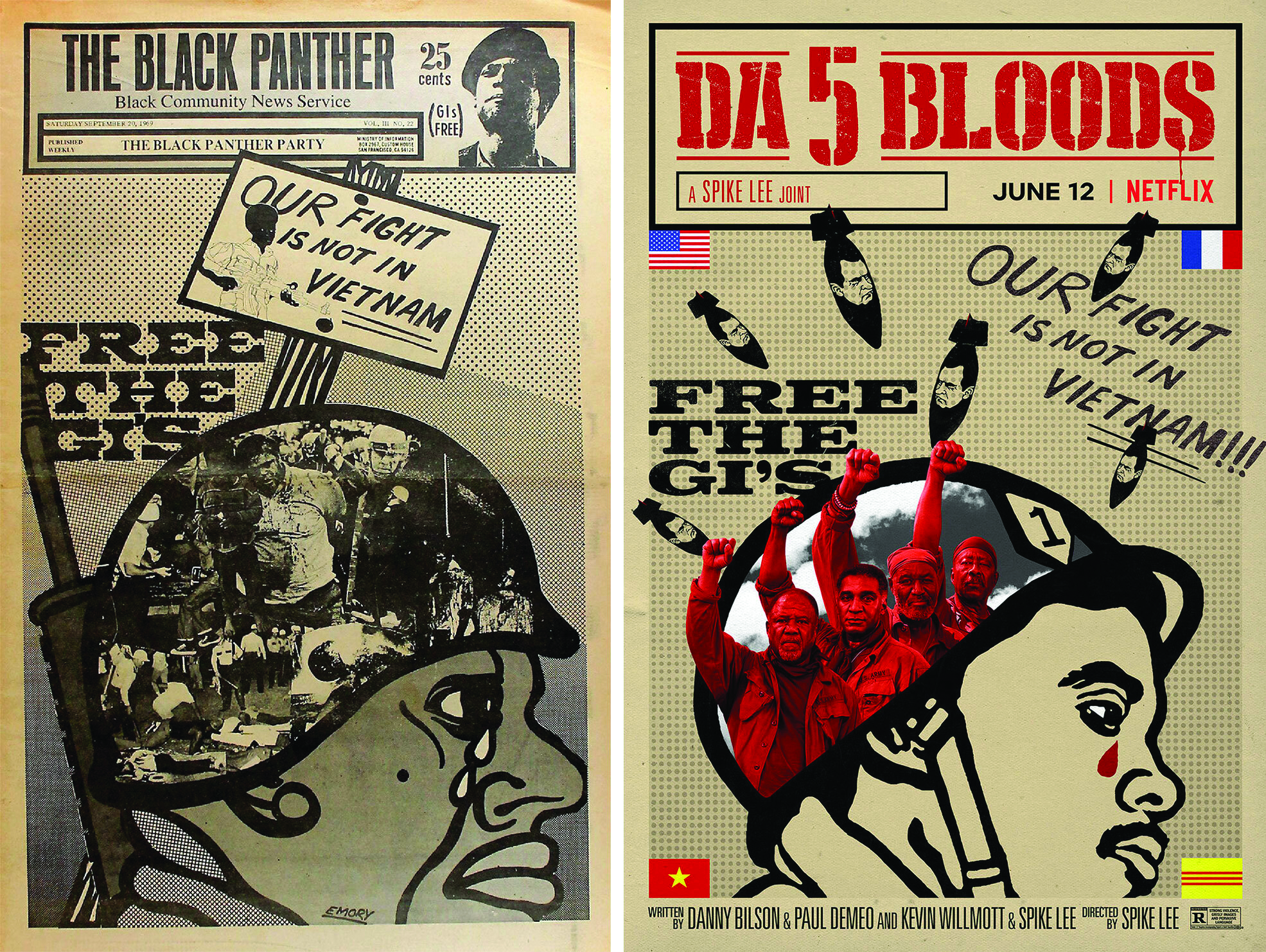

Posters by Emory Douglas

Public libraries have seen better times. In many parts of the United States, they are no longer the center of intellectual and community life that they once were—or, at least, once aspired to be. It is surprising then, given the decline of the public library in general, that in the San Francisco Bay Area, one public library serves not only as an educational resource but also as a gestating archive, a living body of sorts, pulsating and breathing and energizing anew. In the case of the Oakland Public Library, this seemingly breathing, pulsating body continues to serve as a living reminder of the role the Black Arts Movement played and, in many ways, continues to play, in the Bay Area. In the postwar period and especially in more recent decades, the Library has become a nutritional conduit, connecting key elements of Oakland’s political and artistic past and continued struggles in our national and global present. Today, the Oakland Public Library serves to remind not only of the significant role that the Black Arts Movement has and continues to play, but also the way in which this movement was an early effort at decolonizing Western ideas of what constitutes revolutionary artistic practice.

The Black Arts Movement—a movement whose name is often abbreviated with the succinctly impactful, three-letter onomatopoeic imperative “BAM”—began in 1967. BAM perhaps reached its most powerful form by 1980. Its association with the Civil Rights Movements, as well as its affiliation with the Black Panther Party and the Black Power campaigns, gave BAM in its earliest days, its focus on revolutionary cultural reconstruction. The Black Panther Party and BAM sometimes appear almost inseparable. As such, it may not be surprising to find that the Oakland Public Library is part of an ongoing effort to bring the artistry, the effort, the emancipatory struggle visualized and nurtured by the art, to contemporary efforts to end systemic racism and racial injustice.

Overshadowed to a great extent by San Francisco’s iconic status as a center of social transformation in the 1960s, Oakland was nevertheless a center for cultural revolution. The East Bay, in general, never seems to get the recognition it deserves as an epicenter of artistry, something that films like Black Panther (2018) attempt to address. But it is Oakland Public Library that is at the vanguard of this effort to honor BAM as an underappreciated avant- garde art movement. Dorothy Lazard’s entry on the Library’s website offers up some of the key dimensions of BAM as manifested in the Bay Area broadly—and, more specifically, in Oakland and Berkeley. Lazard notes the way in which BAM echoed some of the celebrations of Black culture associated with the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Yet Oakland in the 1960s proved to be fertile territory not only for a similar embrace of the arts in the name of solidarity, but also for presenting a superstructural message, an ideological imperative, to think about Black culture and the Black body differently. Lazard makes clear that with its emergence in 1967, BAM helped fuel these energies into a future-oriented project: “As the Black Arts Movement grew, galleries and cultural centers sprouted all over the East Bay in storefronts, church basements, and private homes. African Americans were hungry for representation, and African American artists took it upon themselves to make art that expressed what they were feeling politically and personally.”

Yet in the voluminous literature on the (European and North American) avant-garde, there is rather little, comparatively speaking, about the Black Arts Movement. Part of this absence is the term itself: avant-garde. The idea of an artistic avant-garde was articulated in 1825 in a text most often attributed to the French Utopian Socialist Henri de Saint-Simon. Saint-Simon saw in the role of the artist an important figure for transforming the existing social order, even as he—and more specifically, associated members of the nineteenth century Utopian Socialist movement—engaged in colonizing practices of their own—for example, in Algiers. Here is a brief excerpt from the text attributed to Saint-Simon, showcasing what he believed should be the newly significant role for the arts in the realm of social and cultural change:

It is we artists who will serve as your vanguard; the power of the arts is indeed most immediate and the quickest. We possess arms of all kinds: when we want to spread new ideas among men, we inscribe them upon marble or upon a canvas; we popularize them through poetry and through song; we employ by turns the lyre and the flute, the ode and the song, the story and the novel; the dramatic stage is spread out before us, and it is there that we exert a galvanizing and triumphant influence.

The immediacy of the arts, its power as “the most immediate and the quickest” form of spreading, popularizing, influencing is still crucial for us today. How else do we explain the continued allure of aesthetic experiences as well as the deleterious effects of social media forms, from Twitter to TikTok, with their powerful visuals, often full of detailed information but also very short on facts?

In recognizing, perhaps even celebrating, the continued power of avant-garde criticality, we cannot and should not ignore the ways in which certain Utopian Socialist ideas, and European Enlightenment ones as well, became so readily aligned with colonialist and racist ideologies. Yet there is something both critical and communal in Saint-Simon’s concept of the avant-garde which has great use today, still, in thinking through what decolonizing the European avant- garde might mean.

Amiri Baraka’s 1964 poem “Black Dada Nihilismus” represents the kind of simultaneous examination and disruption of European avant-garde traditions, a simultaneous examination and disruption that is evident in much of the work of the Black Arts Movement. Born Everett LeRoy (LeRoi) Jones in 1934 in New Jersey, Baraka changed his name in 1967 to Imamu Amiri Baraka (“spiritual leader, blessed prince”) in response, according to some, to the murder of Malcolm X in 1965. Baraka would later drop “Imamu” from his name. His iconic poem, “Black Dada Nihilismus,” is ideally played from the 1964 recording the poet made with the New York Art Quartet, an all-Black jazz group. But in written form, the poem showcases the ongoing tensions between conceptions of the “avant-garde” as an artistic and revolutionary concept and the concomitant, ongoing Western exploitation that allowed for both colonialism and system racism: As Daniel Won-Gu Kim suggests, Baraka’s language—not only in his poem, “Black Dada Nihilismus,” but in others of his works as well—is far from radical when situated in the tradition of the European avant-garde in general, movements like Dada (1916-1923) in particular. Baraka’s words provoke, they shock, they challenge, they are violent—but they also show ineffectiveness of language, of art, alone. Baraka was jailed for poems like “Black Dada Nihilismus,” poems that were deemed incendiary. This imprisonment seems today, but perhaps not for Baraka at the time, ironic: An imperative for silence in spite of the history of slavery and racial injustice to which he was responding and to which he was trying to bring broader public attention. Baraka was successful in his provocations in other ways as well; Won-Gu Kim suggests that Baraka found in Dada key tools for, “destroying the degraded language logic of bourgeois Western rationality.”

The troubling bind in Baraka’s poem “Black Dada Nihilismus” of using language, using art, even if they are not weapons in the sense of a military avant-garde, finds expression in the work of the Black Arts Movement broadly, and in BAM’s Bay Area manifestations more specifically. Here BAM reminds us that a revolutionary avant- garde might need to be rethought as a “vanguard.” The etymology is important here, though, for even as writers and scholars try to disassociate BAM from a Western-centric, colonial idea of an artistic avant-garde, the term “vanguard” still alludes to the same structures, the same system, the same language—in this case, French—that justified colonial ideas of exploitation, theft, rape, murder under the disgustingly hypocritical guise to “civilize.”

There were a great number of artists affiliated with BAM and working in Oakland, Berkeley, and the Bay Area in general. The writers Ishmael Reed, Marvin X, J. California Cooper, and Reginald Lockett, offered engaging, inspired words. The Bay Area Black Artists (BABA) Collective became a prominent force. Creatives such as cartoonist Marie Turner, mixed-media artist Maria Johnson, musician John Handy, as well as many others—James Lawrence, Carol Ward Allen, Casper Banjo—all exhibited or performed. Bay Area college factory, too, brought revolutionary visibility to the issue of racial justice and in hopes of challenging systemic racism—Claude Clark at Merritt College, among them. Ted Potiflet, a graduate of my own institution—then known as California College of Arts and Crafts—became a notable printmaker and photographer.

Exhibition venues and opportunities for community gathering flourished in the Bay Area as a result of the influence of the Black Panther Party and the Black Arts Movement. Notable in the East Bay were the Rainbow Sign on Grove Street in Berkeley, Samuel’s Gallery—owned by Samuel Fredericks—in Oakland’s Jack London Village, and the Ebony Museum of Art owned by Aissatoui A.Vernita in West Oakland and which, for a time, had a second space also in Jack London. The Rainbow Sign was a particular standout, hosting an impressive array of performers and artists as part of the cultural center’s programming: the singer Nina Simone, the writers Maya Angelous and James Baldwin, and the sculptor Elizabeth Carlett all visited.

Notable among this impressive list of East Bay figures is Emory Douglas, now 79 years old, a member of the Black Panther Party beginning in 1967 and its original Minister of Culture. Douglas’s artistic influence can be seen in its historical context in the ongoing Black Power exhibition in the Gallery of California History at the Oakland Museum of California as well as in recent work, including in the posters for Spike Lee’s 2020 film Da 5 Bloods, and in appearances at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an institution which only recently acquired a collection of some 30 issues of the Black Panther newsletter, dating 1969-1970, many of which feature Douglas’s now iconographic work.

The vanguard, if not also avant-garde, work of BAM is undoubtedly the reason that contemporary cultural institutions turn to the Bay Area, and to the East Bay and to Oakland in particular, to showcase the continued cultural but also social and political influence of the Black Panther Party and the 20th century efforts at addressing, ideally eliminated, systemic racism and racial injustice. Even if these goals at times seem far from achieved, a variety of venues and associations in the Bay Area—the Eastside Arts Alliance, the Black Cultural Zone, the Malongo Casquelourd Center for the Arts, and the Art of Living Black exhibitions—all show BAM’s continued influence. Oakland Public Library’s ongoing commitment to documenting not only BAM’s history but also its continued Bay Area presence is itself part of this vibrant landscape— a living, breathing monument, an enduring and active reminder of what decolonizing the “avant-garde” can look like.

Thomas O. Haakenson, California College of the Arts

FLOWERS OF MEMORY