Buffett saw his life and work for what it was: a brief swell in an ocean of change.

MY DAD IS NOT JIMMY BUFFETT. Six years his junior, and a native Conch rather than an Alabaman transplant, my dad never had a Top 40 hit. A Navy brat (and later, veteran), my dad never played the Troubadour. Now retired, living on a teacher’s pension, my dad never leveraged a themed gift shop into a billion-dollar franchise.

But if you squint, the lines begin to blur: Both are named James. Both spent their formative years in Key West. Both had fathers and grandfathers who made their lives on the sea. And both eventually traded Florida for New York, though not without suffering the consequences of all that salt-sprayed sunshine.

In the wake of Jimmy Buffett’s passing, I can’t help but read between the lines. It’s hard to see photos of Buffett’s island years, fooling around in cut-off jeans, without thinking of my dad up on a ladder, fixing our roof during the short summers in upstate New York. It’s impossible for me to hear “Treat Her Like a Lady” or “Mañana” without going back to our unfinished basement, dust in the air as he taught me how to use a table saw. Tales of his own island childhood accompanied hummed renditions of “A Pirate Looks at Forty,” both as real and imagined as the other. Through my father, these stories of sailors and smugglers became more than just music. They became part of my heritage. Part of my identity.

For many, this will sound overdone. A songwriter most famous for crooning about cheeseburgers and margaritas hardly seems like a cultural touchstone. But beyond “The Big 8,” the party-centric staples worshiped by Parrotheads nationwide, Buffett’s music offers a kind of “hick wisdom” that’s become almost foreign to modern culture. It’s the same wisdom I gleaned from my dad in borrowed phrases and long-winded yarns, in those backwater anecdotes that taught me how to be human.

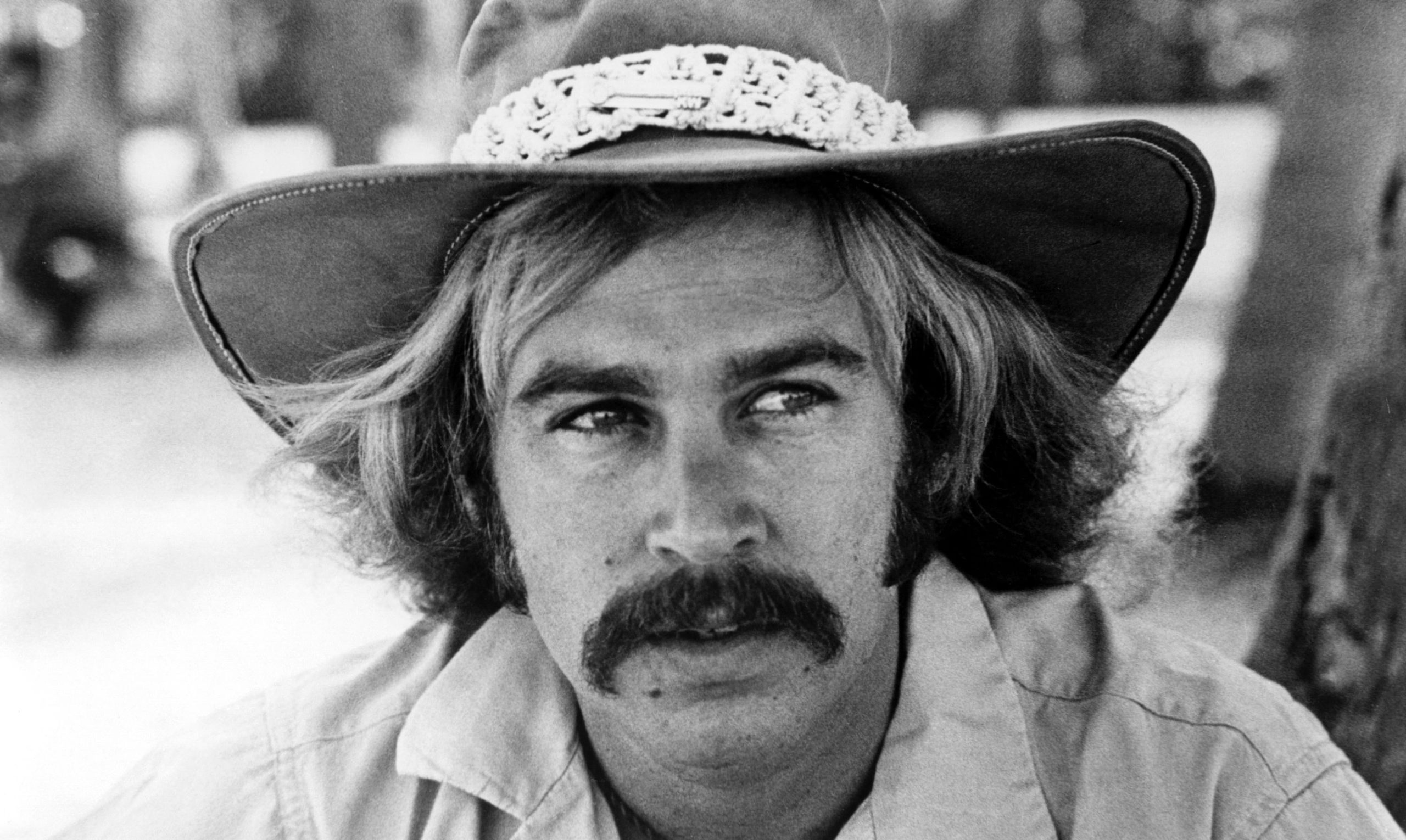

Jimmy Buffett c. 1970s. Photograph by Scott Newton

Jimmy Buffett’s first album was a flop. Released in 1970, Down to Earth sold a mere 324 copies. But somehow, sometime between their last year at Key West High and enrolling at Pensacola Junior College, my dad and his friends caught wind of it. I like to think they listened to “The Captain and the Kid” again and again, the grandfatherly captain reminding them of the sailors that filled the island back then (not to mention the track dedicated to their favorite superhero, Captain America).

Buffett himself wouldn’t set foot on Key West until 1971. Tired of the Nashville scene and escaping a failed marriage, he shacked up with musician Jerry Jeff Walker in Miami. Due to a scheduling error, they took an impromptu drive down state route A1A, busking their way across the Keys.

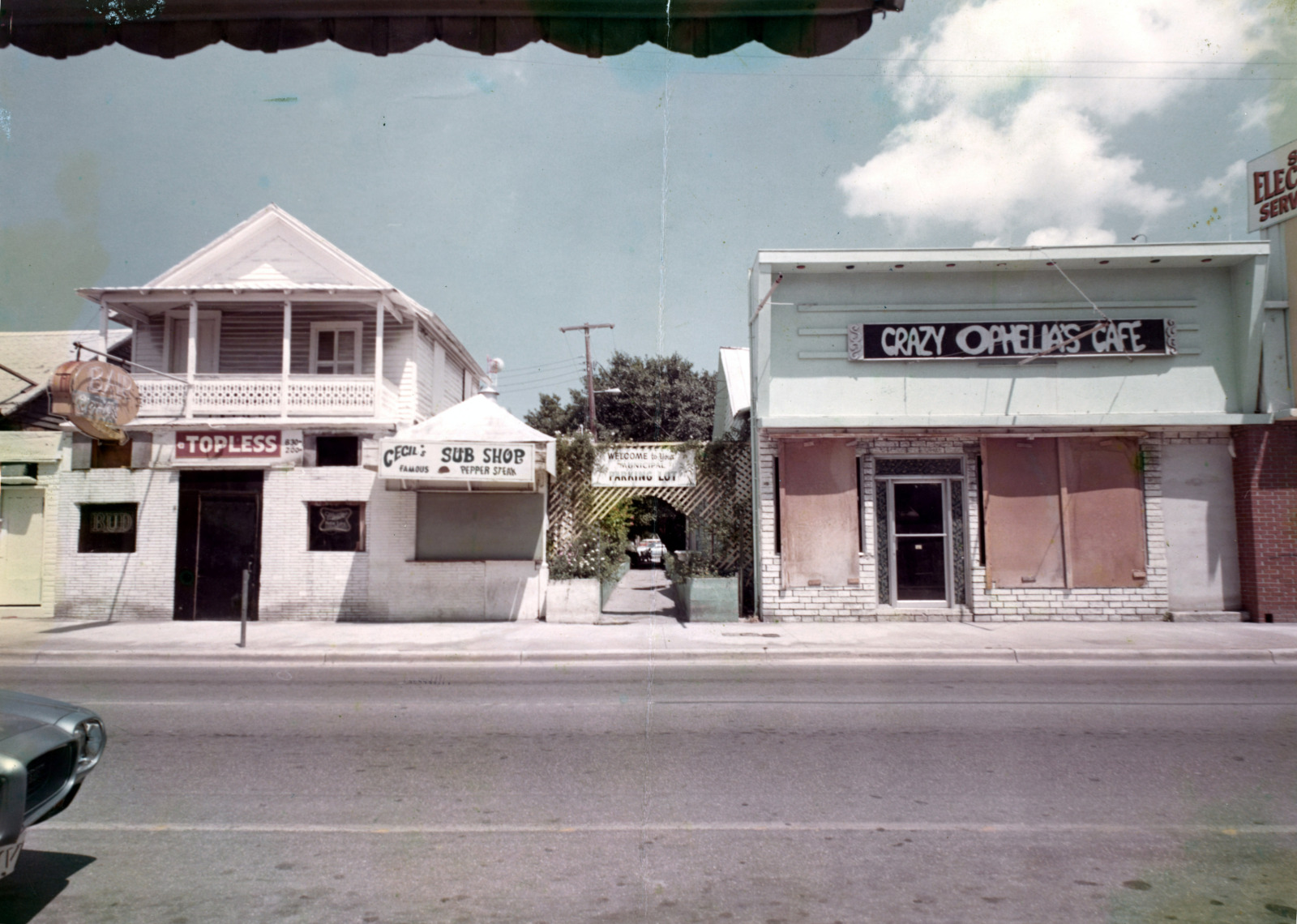

Jimmy was hooked. Within months, he’d moved into a one-room bungalow on Ann Street, a block from my dad’s childhood home. He played for drinks at the bars along Duval Street, working shrimp boats to make ends meet. He landed his first official gig at Crazy Ophelia’s, before moving on to Howie’s Lounge and The Chart Room, where he met characters like Phillip Clark—the downtrodden smuggler from “A Pirate Looks at Forty.” Soon enough, he was fishing tarpon with Jim Harrison, playing Hank Williams songs by Tennessee Williams’ pool, waking up in strangers’ beds, days drifting by as he wrote ballads like “I Have Found Me a Home” about the quiet simplicity of island life.

Buffett had discovered my dad’s Key West; an underdeveloped salt marsh at the periphery of America. Back then, it was an isolated island of bar brawls, diving schools, Cuban immigrants, “bohemian” men, cyclical storms, hard-drinking artists and hard-edged seamen—a place where people escaped to, looking for a better life. A place where kids still played stick ball in vacant lots. Where submariners locked themselves into The Brown Derby (now the Green Parrot). Where, on his first night in town, Truman Capote was robbed during a late-night liaison in a motel-owner’s trailer.

When my dad drove his VW bus up to Pensacola, he knew he wouldn’t find anything like it. But opportunities on the island were scarce. Unless you were in the Navy, the “import-export business” (his euphemism for the drug trade), or your name was Jimmy Buffett, you had to look elsewhere. My dad, never the greatest student, wanted to be a patternmaker. But his draft number was called during his first semester. By the time A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean—Buffett’s first Keys-era record—debuted in 1973, he’d been shipped from boot camp to Vietnam and back again. By 1974, when “Come Monday” broke into the Billboard Top 40, he’d transferred into the fleet. While he was in Scotland, hearing Buffett on the radio reminded him of the home he left behind—the one he already knew he could never really get back.

Jimmy eventually learned the same lesson. In 1977, he sublet his apartment to Hunter S. Thompson and moved to St. Barts, where he lamented the island’s “growing commercialism” in an interview with Rolling Stone. But Key West had already gone through several waves of commercialization. In the late 19th century, it was the most prosperous city in Florida. Cuban immigrants fueled its booming cigar-rolling industry. “Wreckers” salvaged the Gulf. Salt was mined. Sponges were harvested. In fact, if it weren’t for the Great Depression (and a devastating hurricane in 1935), it’s unlikely my dad’s family could have afforded even their modest trailer on Greene Street.

Key West, like the rest of America, was a land of booms and busts, of opportunity and poverty. It was a quirk of history and geography that made it such a strange place to grow up—and such a well of inspiration for the artists and troubadours who moved there throughout the 20th century. Closer to Havana than Miami, sun-soaked yet hurricane-battered, and post-industrial before it was cool, the island was unique. But like all quirks of history, it was bound to its own time, destined to change as the years rolled by.

Country music is inseparable from nostalgia. Indeed, the genre has been looking back through rose-tinted glasses ever since the Grand Ole Opry popularized it in the 1920s. For a century, country songs have praised down-home cooking, mourned the drudgery of shiftwork, and suffered through marriage and its discontents, always setting its characters’ lives against the open-air freedom of the West. The promise of America—its dreams, its past, and its unrealized future—is the ghost that haunts the genre. As critic Patrick Anderson observed, in the midst of the “outlaw country” movement of the 1970s, “the country singer, as an embodiment of his audience, looks to the past, mourns a rural paradise lost.”

Jimmy Buffett never quite fit into country. He got his start in New Orleans, playing for change on Decatur before stumbling into a gig at the Bayou Room on Bourbon Street. And although he landed a two-record deal with Barnaby Records during an abortive stint in Nashville, the failure of his first album led the label to bury the second.

The truth is, Buffett hadn’t yet found his muse. The island life provided the raw material for what critics have called his “shrimp-boat,” “tropical,” and “Gulf & Western” sound. Jimmy himself called it “drunken Caribbean rock n’ roll.”

However, Buffett owes a debt to country music. His lyrics, especially the mid-70s work for which he’s best known, tackle many of the same “everyman” themes. While his characters and locales are unique, his songs explore addiction, depression, regrets, lost love, daydreams, monthly bills, dodging taxes, letting loose, small-time crime, big-time hangovers, fried chicken, honeysuckle vines, and long trips home. They range from the roguishly poetic (“He Went to Paris,” “Wonder Why We Ever Go Home”) to the almost surreally folksy (“Life is Just a Tire Swing,” “Big Rig”). At their best—like my dad’s childhood stories—Buffett’s songs are meandering, melancholic slices of life, recalling times and places that have faded into myth.

The legends of country music, from Patsy Cline to Hank Williams, are rightly recognized for lionizing the struggles of rural Americans. But they’re also known for popularizing colloquial American English. And like theirs, Buffett’s songs are stuffed with mottos and adages; lines that border on cliché, yet remain essential parts of the American lexicon. Sayings like “talk is cheap,” “say what you mean and mean what you say,” and “no free rides” instantly evoke a classic American worldview—ways of life as much as turns of phrase.

But what connects Jimmy Buffett to country also sets him apart. Rather than simply mourning the past, his work confronts lost ways of life, showing how those lifestyles have always been—and always will be—precious and precarious. His songs aren’t just elegies for that “rural paradise lost,” but portraits of times and places that are always on their way out, no matter how hard we cling to them. Even in the late ‘70s, when he’d landed on the Caribbean-themed sound that carried him through the next two decades, there’s a sense of longing in his lyrics—an understanding that this too would pass, regardless of how well he sang about the good times.

It’s the same thing I hear in my dad’s voice when he reminisces about the Keys. Losing an outboard motor halfway to Cuba, throwing rocks at Hemingway’s house, hanging a shark from the gym rafters as a senior prank… There are things that cannot exist outside a particular time and place. But the lessons we draw from them transcend those limitations, while reminding us to appreciate every moment for what it is: something we’ll never get back, except through music and memory.

There are things that cannot exist outside a particular time and place. But the lessons we draw from them transcend those limitations, while reminding us to appreciate every moment for what it is: something we’ll never get back, except through music and memory.

Much like Buffett, my dad has a mental phrasebook of folksy sayings, passed down through the generations. He, in turn, passed this “hick wisdom” on to me. Hardly a day goes by where I don’t consult it.

Some of it is simple and universal. Phrases like “measure twice, cut once,” “locks are for honest people,” and “don’t shit where you eat” offer guidance for practically anyone. Others are more judgmental. But unfortunately, this world is full of people who are “tighter than a crab’s ass,” who “don’t know their ass from first base,” and who are “about as sharp as a marble.” Or, my personal favorite—and one that increasingly typifies the American psyche—people whose only creed is “me first and fuck everybody else.”

Still others, as with some of Buffett’s lyrics, sound absurdly provincial: “like a one-eyed dog in a butcher’s shop,” or “can’t beat that with a stick,” or the long list of things that would “make your pecker fall off.” These phrases instill not only meaning, but feeling. They’re experience by proxy; not exactly knowledge, but that elusive “hick wisdom” that remains relevant, even as the ways of life that inspired it fade to obscurity.

Consider “sharp as a marble.” An ironic inversion of “sharp as a tack,” the slight captures the dry, working-class sense of humor shared by those who actually grew up playing games like marbles and jacks. The root phrase—found in print as early as 1912—is an Americanization of a much older saying. “Sharp as a needle” appears in 19th century retellings of “Jack and the Beanstalk,” and usages like “as a thorn” and “as vinegar” go back to a 1678 collection of English proverbs. The latter appears to stem from Latin (“aceto acrius”), potentially placing its origins in antiquity.

Idioms like these are endlessly circulated, repeated, and mangled as they pass from person to person. They pick up local color, lose it, gain it again, then become something else entirely. They’re reflections of both the individuals who utter them and the communities they come from—reminders of not just who we are, but how we came to be.

Jimmy Buffett grew up on the Gulf Coast, mostly in and around Mobile, Alabama. No doubt he picked up much of his hick wisdom the same way I did: from his seafaring family.

My paternal grandfather, Robert Neil Hewitt, was a Navy diver who lied about his age to enlist in the lead-up to World War II. A boxer, dancer, and military hard-ass prone to “prowling and growling” up and down Duval Street, he was the type of person many happily consign to history. But people are imperfect in every era. Today, his sayings sound almost esoteric in their simplicity. They speak to lives of struggle; of making due and getting by, despite the world’s indifference.

One of these—handed down by my great-grandpa, a man who had to swear he wasn’t an anarchist on his two-page immigration papers—sticks with me for its no-nonsense, plain-spoken worldview. My dad would repeat it any time I was faced with a chore I didn’t like. Whether it was mowing the lawn, or washing dishes, or gathering firewood, he’d tell me that “you don’t gotta like it, you just gotta do it.”

Hardly the stuff of poetry. In a “frictionless,” tech-first world that encourages us to “work smarter, not harder” while “living our best lives,” such an austere prescription seems backwards. Wrong, even. But it remains one of the clearest value statements I’ve ever heard, making as much sense to me now as when I first heard it.

These sayings, and the simple, stoic guidance they offer, become invaluable when the world feels unstable. Facing new social norms, rising prices, and unforgiving public discourse, we need the storied sayings of those who came before us—from those who proved that it is possible to face adversity and come out stronger—to provide not just hope, but the discipline that turns hope into action. And sometimes, as Jimmy Buffett often reminded us, that requires a little levity.

I think this, more than any well-deserved reputation for debauchery, is what most endears Buffett’s fans to his music. His best songs aren’t just funny diversions, but stories of trouble in paradise. Especially during his “island years,” when he shopped at Salvation Army and sought shelter in the Monroe County Library, Buffett’s lyrics illustrate the struggles of poverty.

In “The Great Filling Station Holdup,” two hapless criminals rob a gas station with a pellet gun. Thrilled with their haul of fifteen dollars and a jar of cashews, they immediately hit their local dive, only to be “roughed and cuffed” by the deputy sheriff. In “The Wino and I Know,” from 1974’s Living and Dying in ¾ Time, Buffett reflects on his hard-up New Orleans days, sharing the streets with the city’s homeless. And in “Tin Cup Chalice,” another love letter to Key West on A1A, he meditates on simple pleasures, the things you don’t need money to enjoy, that offer themselves up if you know where to look. Like Faulkner with a funny bone, Buffett made hay of whatever was at hand.

Growing up in a poor corner of Upstate New York, these themes spoke to me. My earliest memories come from a camper-trailer outside what would eventually become our home. We didn’t have much. But it was more than enough. The changing of the seasons—the crystal sheen of the first snow, the unfolding leaves of spring and summer, the fleeting colors of fall—were their own kind of paradise.

I think that’s the point Jimmy was always trying to make: that poverty and paradise can coexist. Indeed, they must. For Buffett, paradise wasn’t a place as much as a way of navigating the world; wherever you looked, there it was. But like everything else in life, it could only last so long.

Facing new social norms, rising prices, and unforgiving public discourse, we need the storied sayings of those who came before us—from those who proved that it is possible to face adversity and come out stronger—to provide not just hope, but the discipline that turns hope into action.

In July 2014, I went to a Jimmy Buffett concert with my dad. My uncle Mike, who’d been to one before, told us to be ready early. About five hours early; or an hour after they opened the gates. Late enough to dodge traffic, but not too late to miss the fun.

I knew Parrotheads—of which I’d consider my dad an honorary member—had a reputation for partying. But what I experienced that day at the Great Woods Amphitheater made the most ardent professional tailgaters look tame.

There were jello shots. There were keg stands. There were football games on real sand beaches, shipped in and dumped on the asphalt. There were wet t-shirt contests (including men and women). There were joints and bongs and blunts passed across a sea of Hawaiian shirts. And there were boat drinks. God, were there boat drinks: blended in oversized blenders, poured into kitschy disposable cups, shared with strangers and passersby.

As far as parking lot parties go, it was one of the best I’ve ever attended. 20,000 people, gathered around a common cause. The atmosphere was joyous, cavalier, carefree—like a three-day music festival without the commitment.

The five-hour pre-game has blurred Buffett’s actual performance into a hazy memory. But that’s to be expected. I do remember that he closed with “Margaritaville,” the song that birthed his lifestyle empire, spawning hotels, casinos, and a nation-wide restaurant chain. The song was also Buffett’s only Top Ten hit, peaking at number eight in 1977.

Parrotheads live in Margaritaville. Or at least they vacation there—despite the fact that it’s not a real place. As Jimmy would say: it’s a state of mind, man. But his grandkids will probably thank him for manufacturing it.

In 1996, academic Dawn S. Bowden asked a cohort of Parrotheads where the “real” Margaritaville was. Responses ranged from the obvious (Key West) to the obsequious (“near Montserrat,” where Buffett recorded his 1979 album Volcano). However, nearly all the respondents were sure it was a place to “escape to,” or to “find yourself.” Yet, for me, this is a willful misinterpretation of his work. Indeed, the entire Parrothead lifestyle—which, being a shrewd businessman, Jimmy gladly sold to his fans—misses the point of even his most popular songs.

Take “Margaritaville.” Remembered as a holiday staple—complete with its own Parrothead call and response—his biggest hit is actually about someone using that “booze in the blender” to mask their regrets. It’s a portrait of “Keys Disease,” the apathy and dependence that afflicts people who flee to paradise, only to find themselves drifting, listless, lost at sea. Like so much of Buffett’s work, its lyrics clash with the sunny instrumentation, to the point where fans simply ignore the meaning behind them.

This is what writer Eric Pooley, in a 1998 profile for Time, called Jimmy’s “devil’s bargain.” A clever, introspective singer-songwriter, doomed to entertain “frat boys and alcoholic chicks from the South.” Twenty years later, recognizing his success in selling the island life to Midwestern baby boomers, the New York Times ran another piece on Buffett. Headlined “Jimmy Buffett Does Not Live the Jimmy Buffett Lifestyle,” it mostly covers the business nous that made him the world’s most unexpected billionaire. But it also draws attention to this contradiction at the heart of his fandom.

To concert crowds, he was the master of ceremonies at an endless beach party. To those who listened, he was a pensive romantic who savored the transitory nature of life, even as it slipped past. In all their well-meaning revelry, Parrotheads have mistaken the ritual for the meaning of his music. Critics often made the same mistake, describing his work as tacky “island escapism.”

For most people, that’s all it will ever be. But treating his songs as mere subtropical, escapist fantasies belies the truth he told in his lyrics. More than anything, they were about finding a home, about losing it, about returning to it again and again, even as times changed. His music wasn’t an escape from “real life,” but an attempt to return to it, away from modern demands that value work more than happiness. He sang sometimes solemn, sometimes jovial appreciations of time’s passage, and the constant struggle to find our place in it.

Crazy Ophelia’s Cafe, 615 Duval Street, c. 1970s. Edwin O. Swift, Jr. Collection

Last year, my dad had cancerous lesions removed from his jaw, his neck, his back, his arms and his legs. The worst of these took a lymph node—and a sizable chunk of skin—from just below his ear. The doctors prescribed topical chemo creams, to be liberally daubed over his forearms and shins.

During the brief moment when my dad and Jimmy Buffett shared the Keys, people were more likely to slather themselves in oil than sunscreen. And in that era before widespread air conditioning, island life mostly took place under the sun. Now, the consequences of all that exposure seems obvious. But back then—especially for those who lived and worked on the sea—it was just part of the deal.

When Jimmy died on September 1st, due to complications from a rare form of skin cancer, it was like losing a part of my dad. But it was also a reminder of what makes Buffett’s music unique.

In a year when country music seems resurgent, Buffett’s departure from the genre that inspired him is more apparent than ever. Whereas he saw bittersweet beauty in lost ways of life, modern country tries to claw them back. Chart-topping hits like “Try That in a Small Town” and “Rich Men North of Richmond” peddle self-righteous grievance in lieu of stoic struggle, yearning for an impossible return to an idealized past.

These songs—and the lifestyles they alternately mourn and espouse—speak to a growing number of Americans. People crave the “authentic” ways of life that country musicians (and Buffett) have always swooned over. But these songs lack the wisdom—the hick wisdom that ought to be country music’s purview—to face life’s complexities, to find simplicity where they can, and to accept that nothing stays the same forever.

Jimmy was lucky to inherit that wisdom from his family. So was I. My dad—who was fortunate enough to come of age in a Caribbean community masquerading as a military town, then unfortunate enough to lose it—has always understood its importance.

Not that understanding makes it easier. Losing a way of life will always be painful. Once lost, the people and places that defined it are gone. All we can do is remember them.

After Buffett’s father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1995, he wrote a song (Banana Wind’s “False Echoes”) to commemorate his life. As so often happens with artists and their art, the personal ended up revealing the universal. The song’s chorus, which repeats the line “time ain’t for saving, no, time’s not for that,” illustrates Buffett’s true philosophy, divorced from his stage persona. A heart-rending ballad, “False Echoes” was never performed live.

Jimmy Buffett never gave himself enough credit. Like his critics, he often referred to his work as “pure escapism.” But his lyrics went deeper than that, in the same way that my dad’s folksy maxims are more than just silly sayings.

The truth is, Buffett saw his life and work for what it was: a brief swell in an ocean of change. His songs acknowledge that nothing more reliably threatens a way of life than time itself.

Jimmy’s passing—and the specter of my own father’s mortality—was, in some ways, his final act. A culmination of the themes he spent his life exploring. His death brought me back to my childhood, to my grandpa’s Airstream by the canal, to times and places I can’t get back, not just because that’s when I first heard Jimmy’s music, but because that’s the message he (and my dad) passed down.

Our parents are products and reminders of lost ways of life. Our islands are our personal histories. They’re our stories and sayings—hand-me-down tales not about striving, but merely surviving. They stay with us in our songs, in the adages we lean on when times get tough, and in our collective dreams of a lost paradise.

Jimmy didn’t just grieve the past. He showed us how it became the present. By only looking back, we lose those fleeting moments that are the only time we truly have. Sometimes, it takes someone singing about cheeseburgers and margaritas to help you realize that.