Kawakami’s Paintings of Incarceration During WWII

Chikaji Kawakami (1882 – 1949) spent over three years painting watercolors of life while incarcerated at two internment camps for people of Japanese descent during World War Two. These paintings appear simply as delicate Western-style watercolors of a quiet life at a detention camp. But, from the point of view of an older Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrant, Kawakami’s work responds to the war and the devaluation of Japanese culture by asserting a Japanese identity rooted in a traditional classical past.

As Guest Curator of the Monterey Museum of Art, I curated a selection of 40 of these paintings for Under the Guard Tower: Chikaji Kawakami Watercolor Paintings (August 22—December 15, 2024). Kawakami was 60 years old, a widower and a single parent of six children under the age of 19 when he was deported to Tanforan Racetrack Detention Center in April 1942. His incarceration followed Executive Order #9066 that made enemy aliens of all people of Japanese descent. As a result, 120,000 people—two-thirds of them American citizens—were forced out of their homes and incarcerated for the duration of the war at camps located in isolated places known for their harsh environment, primarily in the Western part of the United States.

Since his arrival from Japan in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1904 at the age of 22, Kawakami had endured for almost 40 years the marginal life of the non-citizen living under a strong anti-Asian climate which had impeded Japanese from becoming American citizens. He had survived in the shadows of the networks created by Japanese immigrants whose insularity had made them the least acculturated immigrant group in the US. While he had studied art in Japan, and painted during his spare time, he didn’t live the life of an exhibiting artist, mixing with members of the Japanese artist community in the Bay Area. Instead, he survived as a porter, a motorcycle repairman, and, just before his deportation to the camps, running his own dry-cleaning service.

His artistic life took a dramatic shift at the camps when, for the first time since his arrival from Japan, he dedicated his time fully to painting. Encouraged by the community of fellow Issei artists at the camps, first at Tanforan and then later in Utah’s Topaz Incarceration Center, Kawakami benefited from the art school for the incarcerated under the direction of Chiura Obata, a well-known Japanese artist and professor at UC Berkeley. Obata advocated art as a way of overcoming the tribulations of unjust incarceration. He saw in art a way of finding peace and calmness at such a troubling time. Eventually, Kawakami became an art instructor at the school during his stay at Topaz.

Kawakami belonged to a generational group that was the most vulnerable because as non-citizens they were the enemy. They felt the most conscious of their cultural background, with traditional aspects of Japanese culture forbidden by the authorities. Among these were any form of allegiance to the emperor, the use and teaching of the Japanese language, the practice of the Shinto religion, martial arts, and the practice of certain Buddhist rituals. In addition, the US government engaged in an anti-Japanese campaign to portray the Japanese as animals, feeble and weak. Confronted with the devaluation of Japanese culture, the Issei responded by reviving and practicing traditional Japanese arts and crafts in the camps. At Topaz, for example, classical Japanese arts were practiced, such as classical dance and the use of the musical instruments of shamisen and koto.

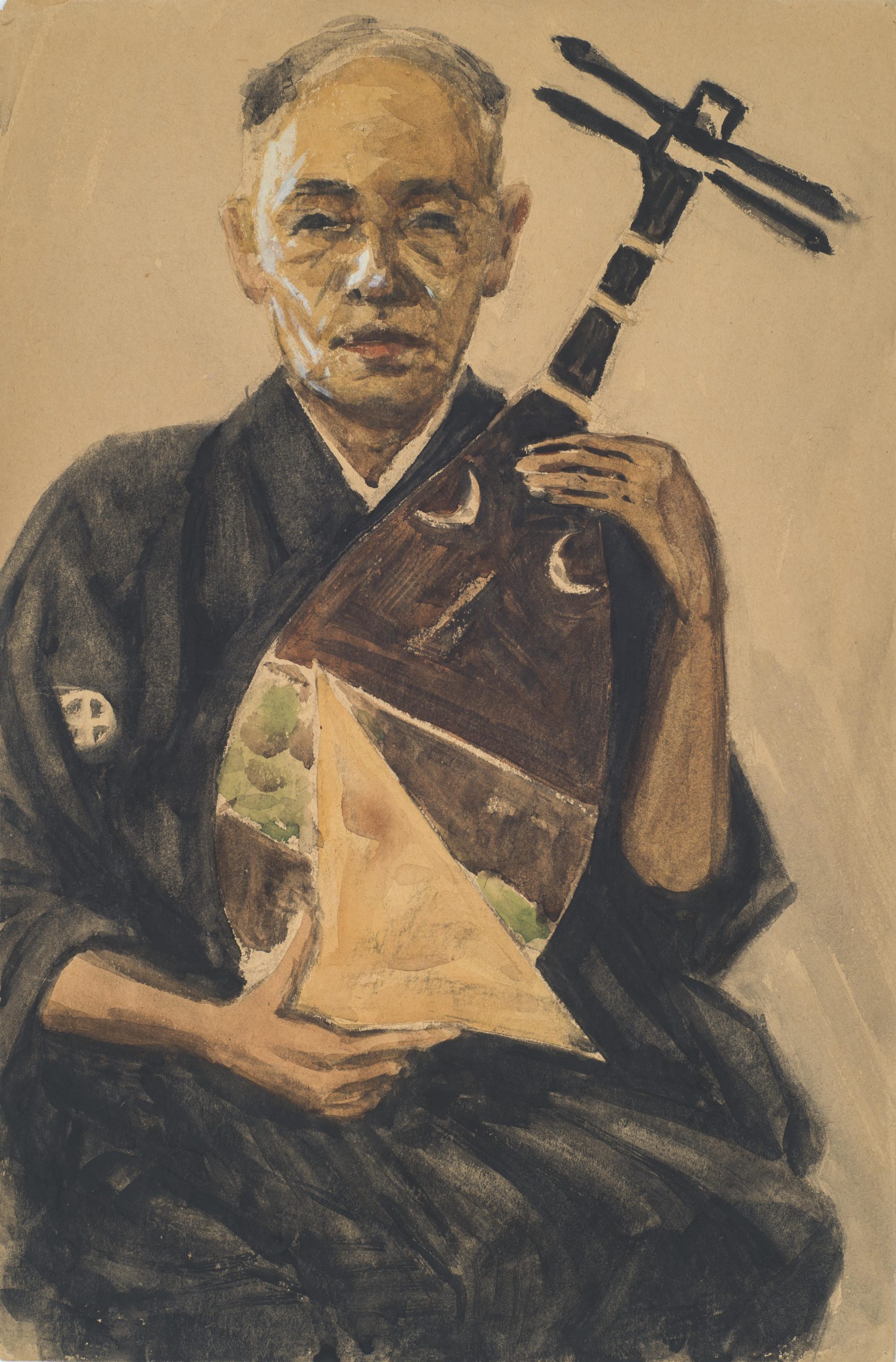

Two of Kawakami’s paintings made at the camps, a self-portrait and a painting of a guard tower, express directly a Japanese identity and also his views about the war. Kawakami painted the self-portrait soon after his arrival to Tanforan in which he depicts himself dressed in a kimono holding a biwa, a musical instrument favored during the Tokugawa period but no longer in vogue in contemporary Japan. This portrait was daring in the context of the war since any associations with traditional Japan was seen as subversive because of their perceived loyalty to the emperor. This painting asserts Kawakami’s identity as a traditional man, but also acts as a counter image to the negative depiction of the Japanese by the US authorities, presenting himself as a calm, educated, and artistic man.

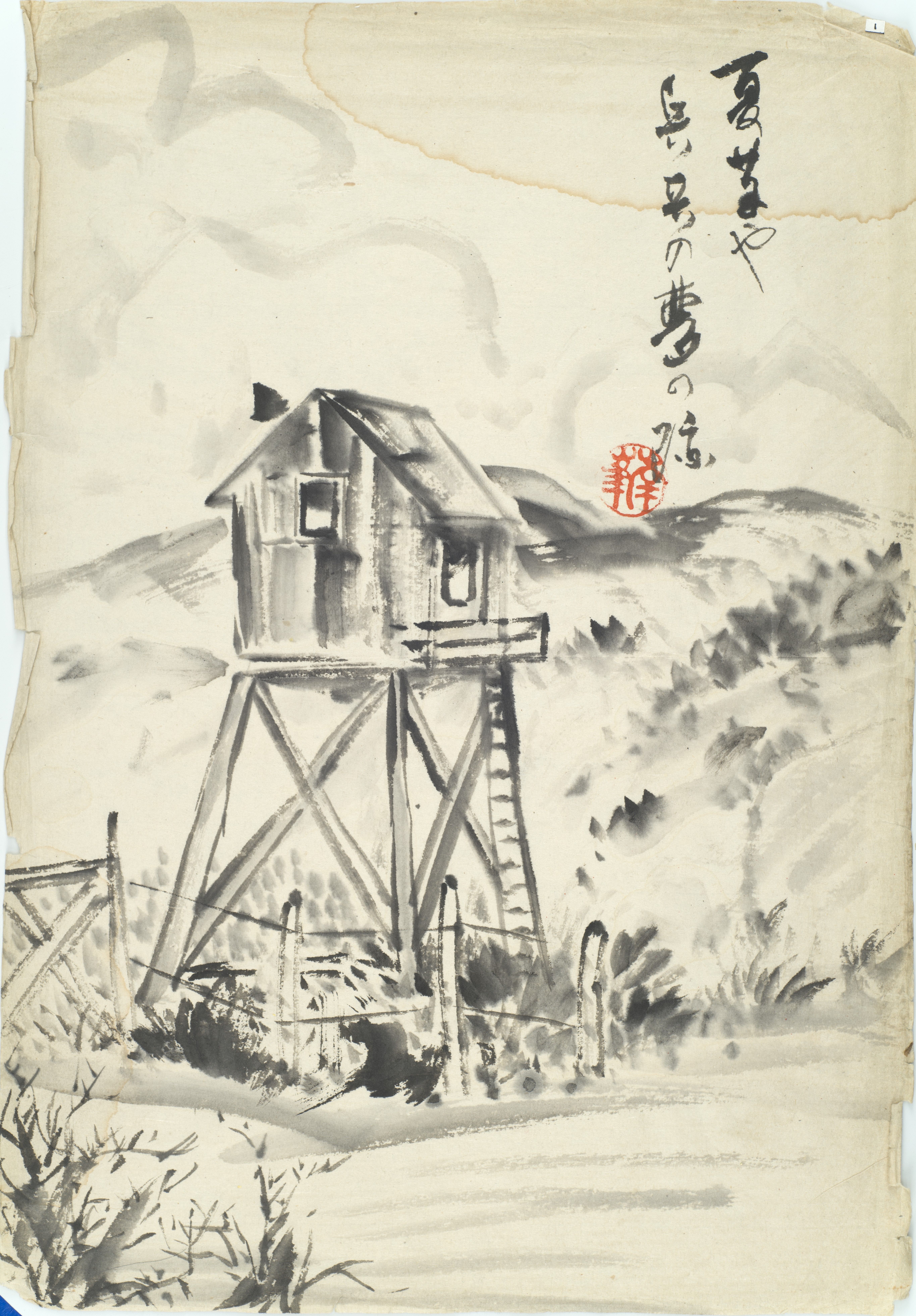

While Kawakami created several paintings of the guard tower using a Western style of painting, one stands out because of his use of haiga, a 17th century style which combines a haiku with a sumi-e painting. Instead of writing his own haiku, Kawakami breaks from tradition by copying a well-known one by the 17th century poet Bashō and illustrating it with a sumi-e painting of one of the guard towers at Topaz. The poem addresses the futility of war by comparing the leaves of summer with the fading memory of dead soldiers. This haiga can be interpreted as Kawakami’s commentary on the war. It also could be seen as his reflection on the death of James Wakasa, a 67- year old man shot and killed by a Topaz guard who claimed he was trying to escape. The event shook the Topaz inmates, who had long expressed fear of the guards’ anti- Japanese attitudes.

Kawakami’s paintings at Tanforan and at Topaz provide a restrained visual documentary of life at these camps that differ from other internees’ artworks. They show scenes of life only from outside the barracks, and from the perspective of somebody observing from a distance. Small groups of people, whose facial features are not shown, promenade in alleys bathed in morning light.

The paintings, as visual documentary of life at the camps, spare the viewer the crowded and unsanitary living conditions inside the barracks, as depicted by internee artists Miné Okube and Chiura Obata. At Tanforan, for example, internees were housed in converted horse stalls which barely covered the stink of the horse manure. At Topaz, people lived in poorly constructed barracks without insulation, and without privacy—entire families lived in crowded places separated only by hanging sheets and used latrines and showers without walls. He does not show the emotional climate of the internees, having forcibly left their homes for barbed wire and armed soldiers. While Kawakami’s restraint could be understood as an aesthetic choice or fear of censorship, it could also be interpreted as a desire to give his subjects three important commodities at the camps: space, privacy, and a dignified presentation.

This restraint is also seen in his landscape paintings of the areas surrounding the camps (the largest group of paintings). They portray a subtle beauty, but they also depict a harsh environment. Topaz was in the middle of an arid desert with extreme heat in the summer and extreme cold in the winter. The area was also affected by winds that blew constantly, covering everything with dust. All the incarceration camps, with the exception of two, were located in arid and isolated places selected with the purpose of breaking the spirit of the incarcerated.

Why did Kawakami—as well as other incarcerated artists—choose to depict the very same environment that caused them so much suffering? Traditionally, the painting of nature has been an important theme in Japanese art, where artists have focused on its beauty. Finding beauty in the place that gave them so much suffering was a defiant act of creativity, one that offered them a sanctuary from the ardors of their everyday life.