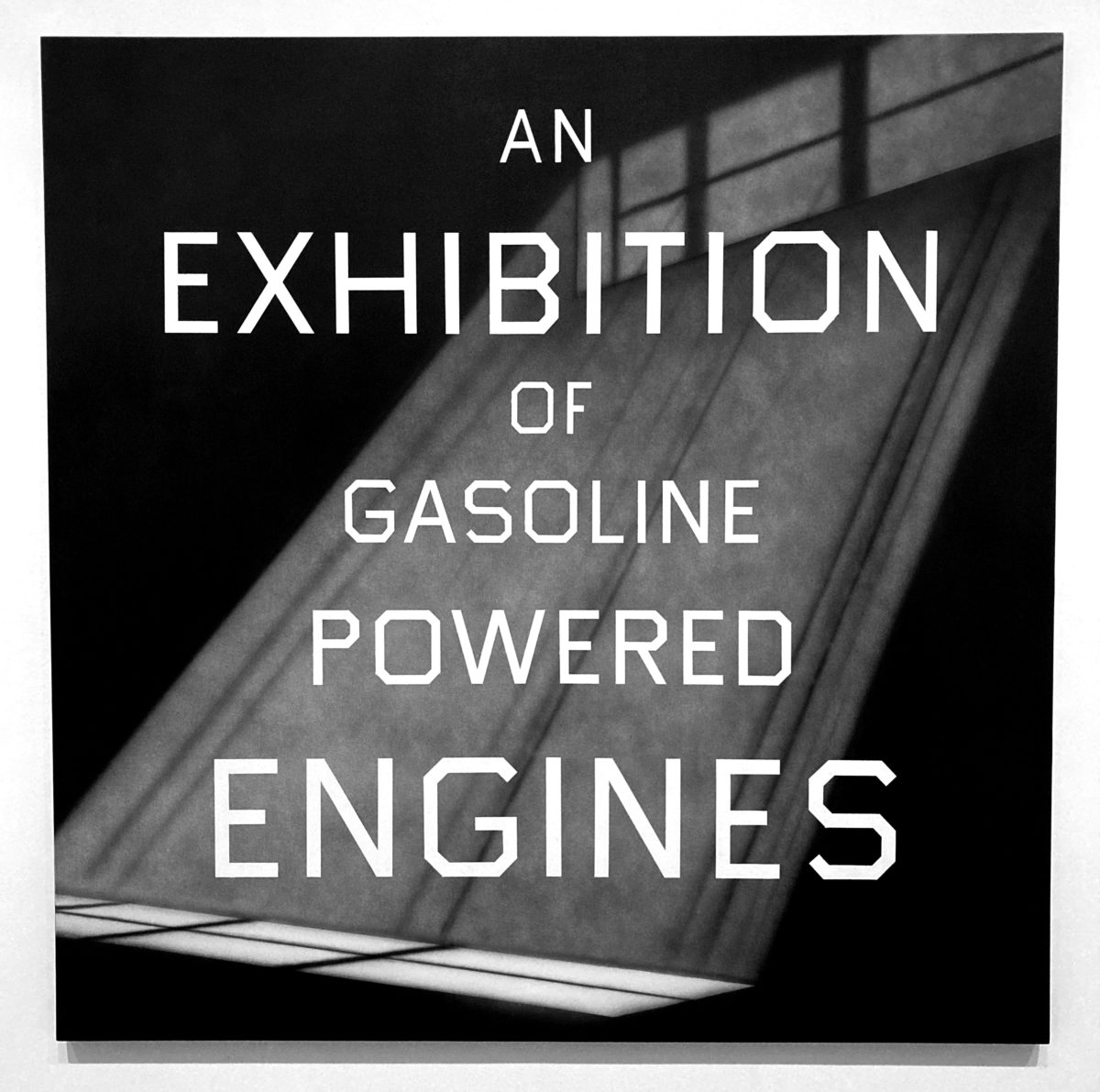

All too soon, a two-part exhibition of works by Ariel Parkinson (1926-2017) closed January 25-26, at House of Seiko in San Francisco.

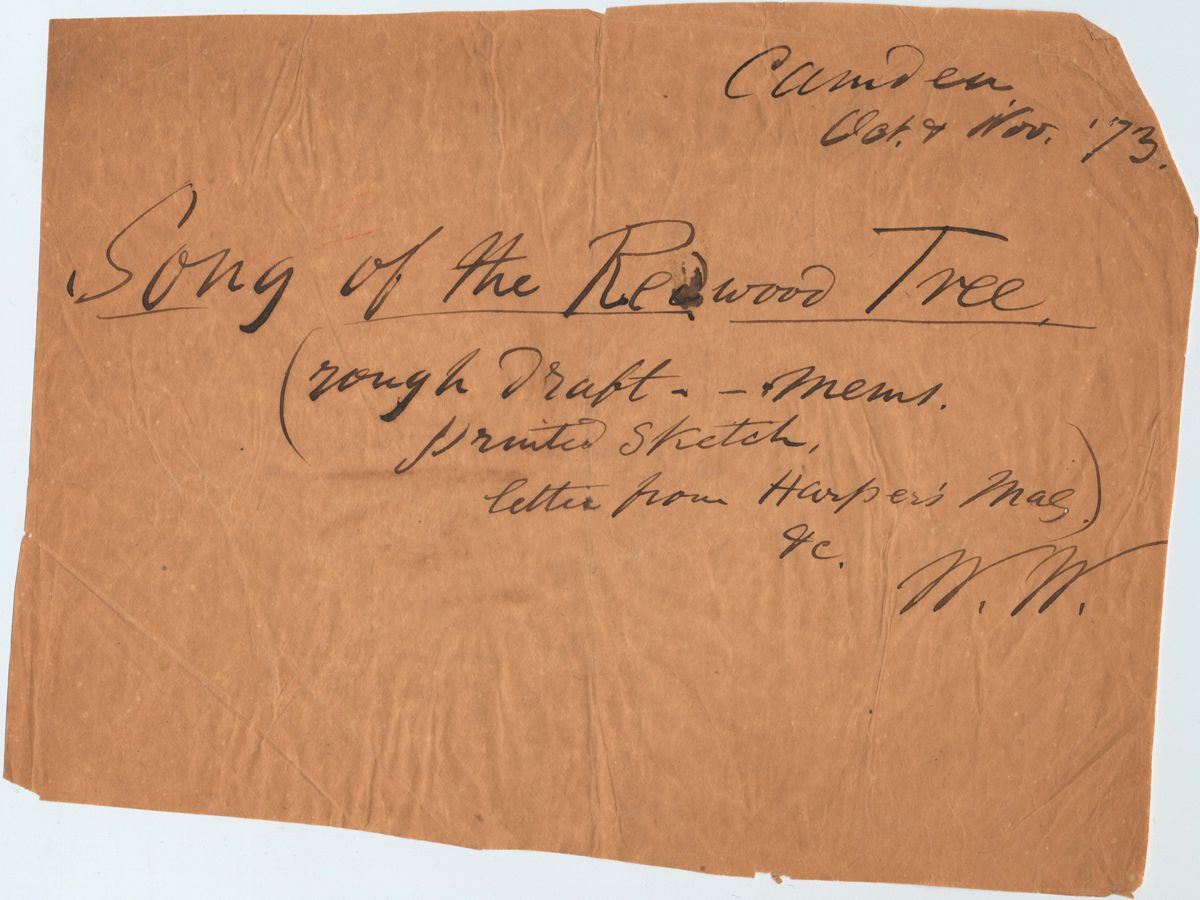

Where to begin—or end—with Ariel, as she always signed herself? From a privileged childhood in Piedmont, California, which extended to excursions on William Randolph Hearst’s private train into Mexico, she went on to Scripps College during the war, to art studies in Paris and Rome in the pinched, cold, European Postwar, to her defining years in San Francisco at mid-century, when she taught literature at Mills College and studied under Rothko and Still at the San Francisco Art Institute. She was married to Tom Parkinson, the poet and Yeats scholar, and forged vital personal connections with the poets of the San Francisco Renaissance, most strongly Robert Duncan, and later with the Beats, most affectionately Allen Ginsberg and, as it were, environmentally, with Gary Snyder.

Her old and eminent friend the art historian Peter Selz later wrote: “Ariel’s work as a painter, sculptor, and designer, as well as her long immersion in literature and poetry, all found their synthesis in her theater designs”; the latter, as Thomas Albright wrote, were distinguished by “dramatic, Wagnerian settings of fire and mist.” In her works the myth-haunted mid-century is preserved in forms large and small, from caricatures to minatory beasts. But she was, always, an activist and, increasingly with the decades, a polemical artist of formidable power and ambition. In her memoir, Ariel (2012), she titled the chapter on the Sixties “Playing Hardball.” Another is called “Intrusion in Space and Other Matters.” It’s a lot to cover, but Zully Adler, the organizer of this exhibition, provides an incisive and eloquent précis of a long, gallant, and singular career (reprinted below). The show was a wonder to behold.

—David Reid

Ariel, Part I & II

December 7, 2024 – January 26, 2025

House of Seiko

3109 22nd Street

San Francisco, CA 94110

The following originally appeared in Ariel, Part I & II, organized by Zully Adler at House of Seiko

For every chapter of Bay Area bohemianism there was also Ariel, carving her own channels between what she called “Beat then Hip, then Rock, Love, the Natural World.” At first, in the late 1940s, she found herself among the poets and playwrights of the so-called Berkeley Bunch. Younger than many and one of few women, she maintained a sharp and sometimes ironic distance from their oblivious masculinity, even if she also enjoyed their “pacifist, anarcho-syndicalist, syncretist, pan-cultural gatherings.” Then she studied at the California School of Fine Arts, painting under Hassel Smith when “Dream was in, and Cosmos.” After that, the dawn of the hippie movement, walking to the Human Be-In with her young friend Allen Ginsberg and holding a sign that read “I Represent the Lower Animals.”

Red Foxes, ca. 1994. Oil on canvas

Sensitive as she was to new tendencies and social change, Ariel also maintained old-world decorum and an archaic, arch-romantic sensibility. San Francisco critic Alfred Frankenstein compared her to William Blake, as if her work belonged to a previous century. Her style skews surreal and whimsical, with a grotesque undercurrent drawn from the darker elements of Art Nouveau. It is seductive but also repellent, producing what she called “the posture of cruel joy”—like the Worm Queen from her friend Helen Adam’s San Francisco’s Burning: A Ballad Opera:

My crown is crusted with carrion flies

And my head is bald and wet,

But the loveliest woman of living flesh

With you will quite forget.

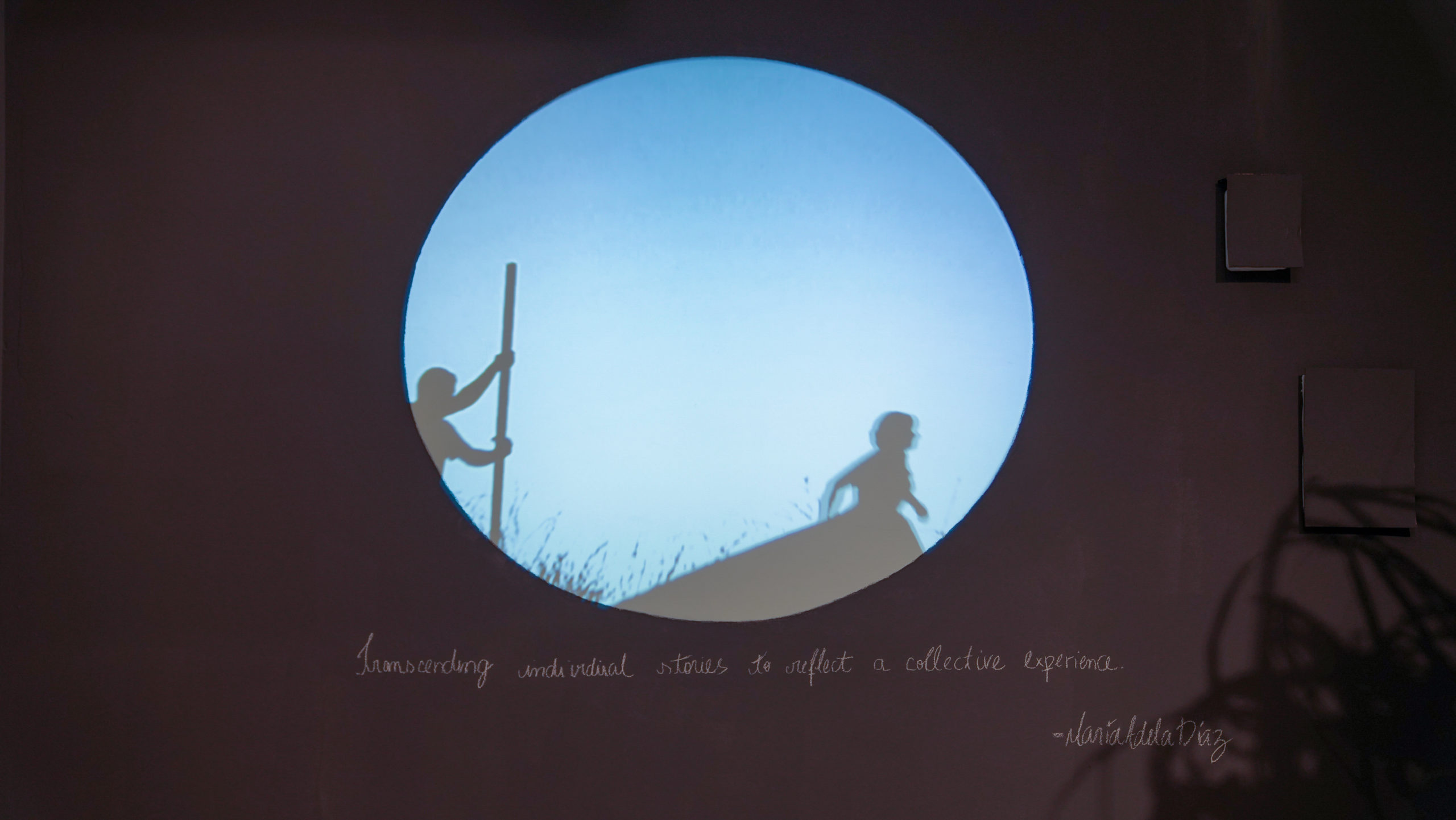

Ariel’s imagery finds its closest companions with characters like this. For her, art was storytelling, and painting carried “the piercing, noble, haunted power to imagine.” Many pieces reference Shakespeare, the Brothers Grimm, and classical mythology. Others conjure what she called the “mists and tempests, sea foam, clouds, smoke, waves” found in the prose of Ruskin. It may have helped that she lectured in English at Mills College, that her husband was the revered poet and professor Tom Parkinson, and that her friends were largely writers. Ariel herself wrote with the verbosity and prosody of a Victorian in recital: “Beyond the writhing fish and the live chickens, the glowing fruit, and the towering gold and cream of Italian baking, glimpses of city towers, glimpses of the grey-green, wind-battered surface of the bay.” That’s San Francisco. Over the decades, she committed increasing efforts to illustration and costume design for opera, ballet, and theater, her artwork put in the service of the stories that inspired her in the first place.

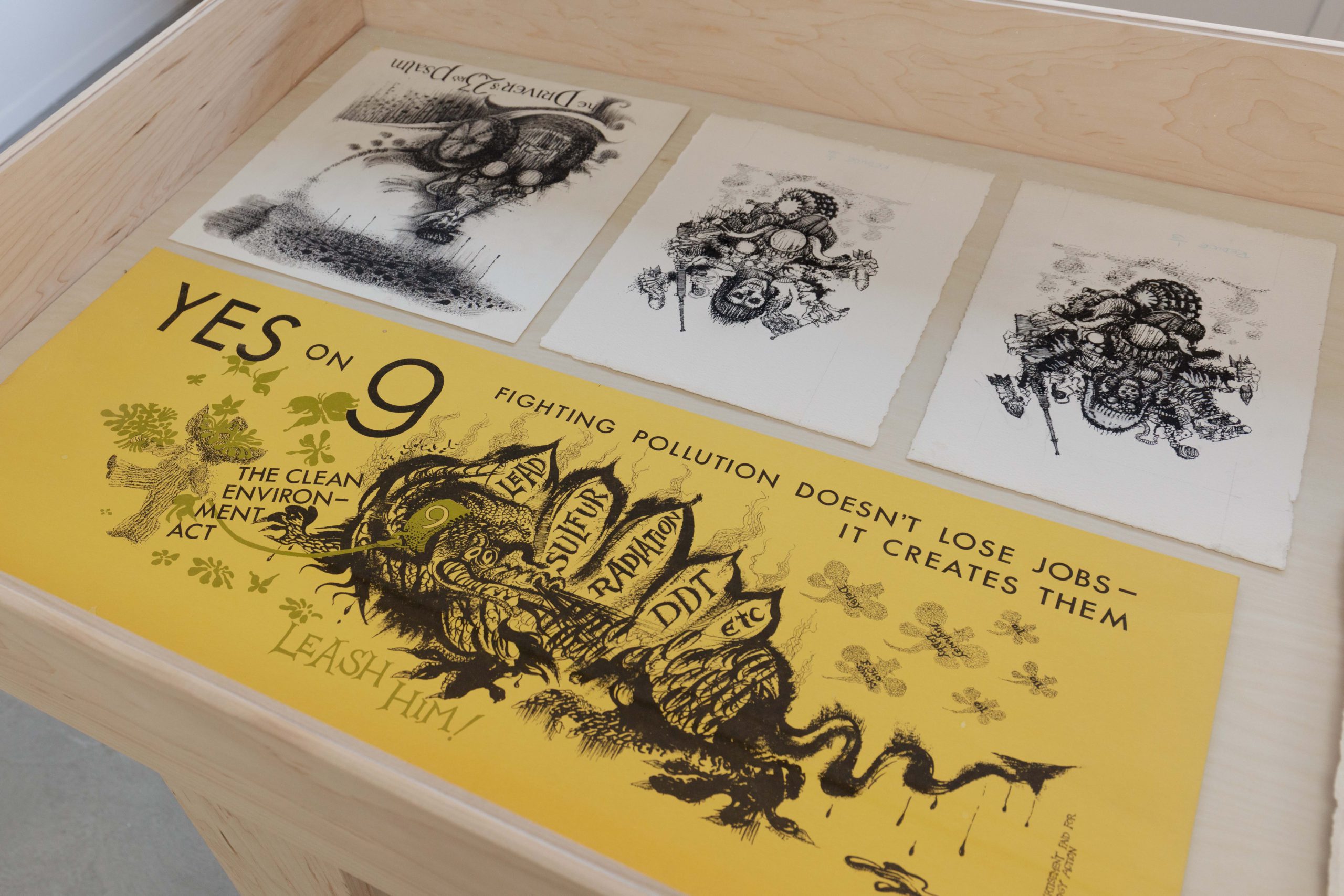

Yes on 9, 1972, offset on newsprint

Nuclear Man, 1972, offset on newspring

Ariel’s creative anchor was always nature. Specifically, “the California of John Muir, Ishi, and Kroeber.” When stuck in the city, she could turn to what Gary Snyder called the inner wilderness, an interior plain of marshes and tidepools overgrown with “Ur-vegetation.” The work that emerged from this wilderness allowed Ariel to found a movement of one: bio-classicism. And when one curator dismissed her painting as a puddle of swamp water, the artist was undisturbed. She drew harsh caricatures of industrial barons and other enemies of the planet. More becoming drawings graced protest banners and guidance on a new municipal project known as recycling. Ariel became a thorn in the side of the Solid Waste Management board. “Garbage is simply resources out of place, and I was its Joan of Arc.”

Ultimately, she left the project of recycling behind and made convincing arguments for doing away with packaging entirely. Whether fearsome, dainty, erotic, or in dissent, the artworks of Ariel are guided by the senses. Paintings and drawings emerged from what she called “various admixtures and applications of the pleasure principle.” Nature was something to safeguard in part because it was interesting to see, feel, smell, and taste. Watching her watercolor spread is satisfying; her human figures are voluptuous. The writers and artists in her company—Robert Duncan, Anaïs Nin, Jack Spicer, Jess, Kenneth Rexroth, Norman O. Brown—were not so different. They exalted feelings, even ugly ones, for how much they could be felt. Neither Ariel nor the Worm Queen play favorites in this realm. They provoke goosebumps as much as induce repose. In the inner wilderness, sensations are vital, but they won’t always make you feel better.