[drop-cap]

California is too big—and too big a subject—for me to approach in any but the most tangential, personal way, focusing on what’s familiar to me, the work that artists and writers do. I went to junior high and high school in Palo Alto and left in the fall of 1968 for Columbia College and New York City, where I’d been born in 1951 and have now lived for more than fifty years. I know California only from my adolescent years and later visits of days, weeks, sometimes months. I’m a New Yorker. I assume that no other American city is anywhere near as significant as New York when it comes to the arts. But I also believe that just about anybody who makes a meaningful contribution to the arts is an outsider of one kind or another. California produces an interesting type of outsider, because unlike New York’s outsiders, who view the outside from the inside, the Californians know the inside from the outside. So when I borrow a phrase from the poet Gary Snyder, “the Great Subculture,” I do so in the belief that subcultures can be great cultures. Maybe all great culture is subculture, in the sense that a rejection of academic values and ideas is involved.

For readers familiar with Snyder’s Earth House Hold, where the phrase “the Great Subculture” appears in the essay “Why Tribe,” I’ll add that I’m not especially interested in the communal and spiritual ambitions that Snyder had in mind in the 1960s. Frankly, Snyder’s “Why Tribe” strikes me as a period piece, with little of the elegance that you find elsewhere in Earth House Hold, in the colloquial austerity of travel writings including “Lookout’s Journal.” What interests me about the idea of the Great Subculture—I like the old-fashioned, rather Victorian capitalization—is the dissent from official culture, a vigorously arrogant marginality that I think shaped the best of creative and intellectual life in California for much of the 20th century. Listen to what Snyder has to say: “We need not look to a model or rule imposed from outside in searching for the center.” This exactingly informal poet isn’t arguing that there aren’t models or rules, but that people must find them for themselves—their own models, rules, center.

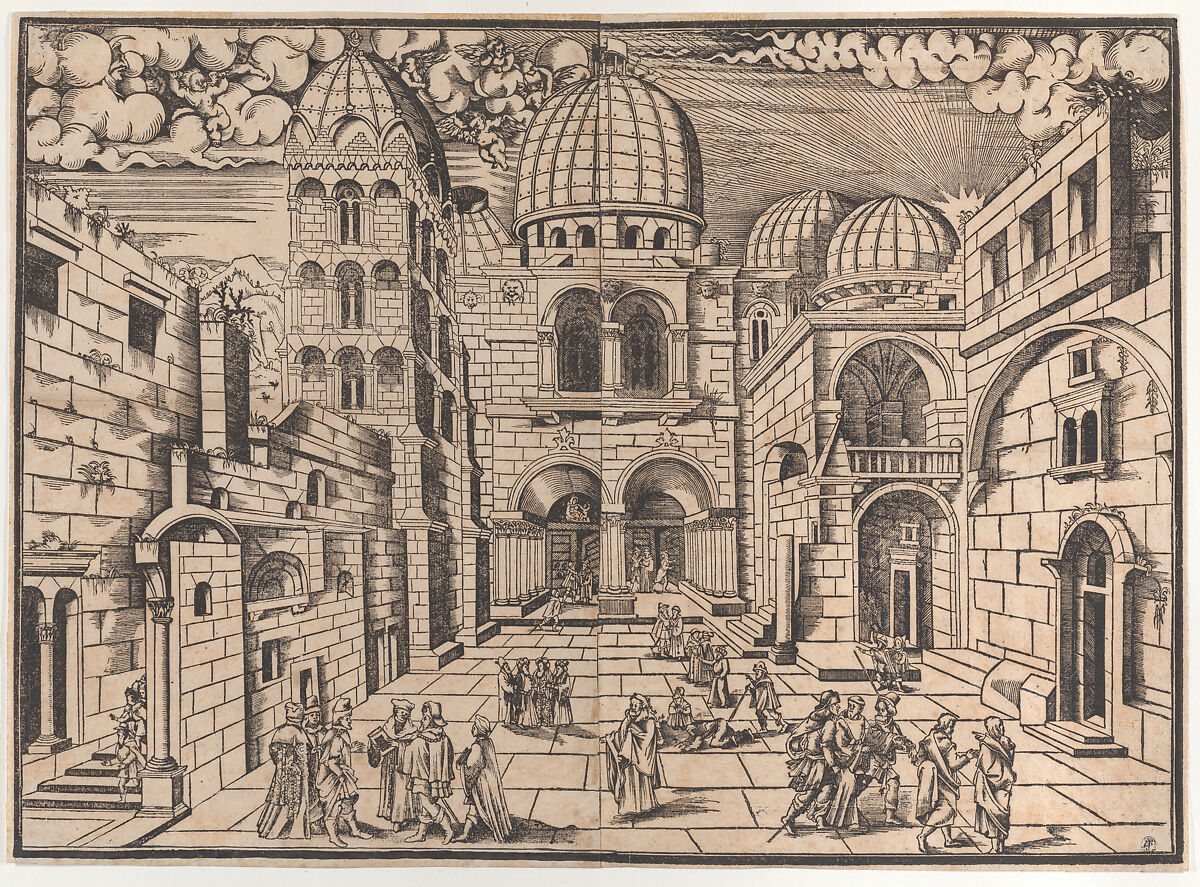

This idea of a Great Subculture, it seems to me, links much of the best of artistic and intellectual life in California: the dazzle of the great Hollywood comedies of the 1930s and 1940s, including Cary Grant’s verbal fireworks with Rosalind Russell or Katharine Hepburn; the labyrinthine thinking in Robert Duncan’s unfinished and unfinishable H.D. Book; the paintings and collages of the artist who went by his first name, Jess, and, along with New York’s Joseph Cornell, turned European Surrealism into American Phantasmagoria; Richard Diebenkorn’s early drawings, etchings, and paintings of Northern California, among them a few imperishable images of bourgeois bohemia; the music that Joni Mitchell made in Laurel Canyon; M.F.K. Fisher’s memoiristic writings about food; Edmund Teske’s overlapping, multiplying photographic images; Frederick Crews’s withering attacks on Freud. The seriousness of culture in California has always involved finding your own center. For Snyder the Great Subculture embraced “Paleo-Siberian Shamanism and Magdalenian cave-painting; through megaliths and Mysteries, astronomers, ritualists, alchemists and Albigensians; gnostics and vagantes, right down to Golden Gate Park.” There’s a touch of madness in the best of California. It’s there in Hollywood, a wild enterprise from start to finish. But there’s also something to be said for the outrageousness of San Francisco’s Barbary Coast as part of this cultural and intellectual ambience, a piratical spirit of comic plunder and pigheaded extremism.

What interests me about the idea of the Great Subculture—I like the old-fashioned, rather Victorian capitalization—is the dissent from official culture, a vigorously arrogant marginality that I think shaped the best of creative and intellectual life in California for much of the 20th century.

What I’m offering is impressionistic. That’s true of any attempt to describe something like the spirit of place. I’ve found myself turning back to the extraordinary histories of American literature that Van Wyck Brooks published several generations ago; their eclipse is undeserved. Brooks brought a kind of genius to evocations of literary experience in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, and San Francisco. He knew how to slip in wonderful asides. While writing about Frank Norris and San Francisco in The Confident Years (1885-1915) he regrets that Norris “had not been able to tell the real story of a real Bret Harte heroine who lived in San Francisco.” This is the dancer Isadora Duncan, another member of the Great Subculture, who was born in San Francisco in 1877. Brooks writes that Duncan “was touring California, at twelve, with her brothers and her sister, dancing and reciting in the little towns.” He pushes farther:

Feeling she was Whitman’s spiritual offspring, she dreamed of a dance that would be worthy of him,—‘the ideal figure of youthful America dancing over the top of the Rockies,’—a system of dancing without a system, following her fantasy, composing her motions all as it were on the wing. The gypsy band of the Duncans and their mother were soon to embark for New York [and] then she was to set out for Europe.

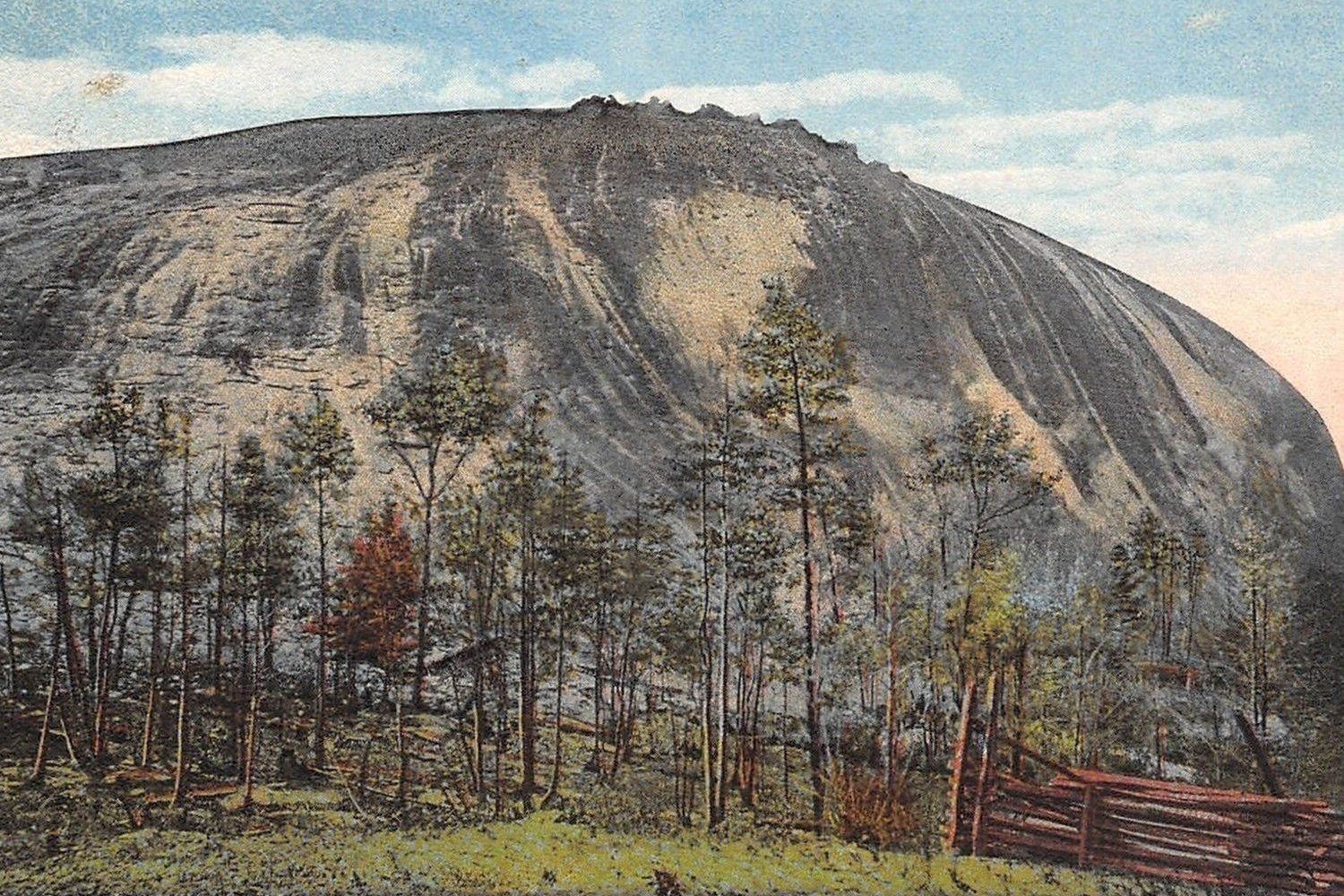

The Great Subculture, as I conceive it, is integral—maybe even essential—to the culture of modernism. California is a part of the story, a region where artists and writers were free of the imperiousness of New York and the sometimes stultifying assumption that you’re at the center of things. Of course there are inhibitions that come with any place you happen to find yourself; regional history can be both a blessing and a curse. New England shaped the poetry of Frost and the early Robert Lowell. The South shaped the novels of Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Eudora Welty. Californians have plenty of history to contend with, but it’s so deep and diverse—the Spaniards, the Native Americans, the Gold Rush, the Gilded Age—that there may be more opportunities to pick and choose than in New England or the South. Who is a Californian, anyway? When I lived there in the 1960s there seemed to be no question that transplants outnumbered natives, but that may have reflected the particular community in which I was growing up, an academic community where people were always on the move when it came to jobs and advancement. But even old California families can be relatively new, at least compared to the deep family roots in other parts of the country. So the arts in California inevitably include recent arrivals and maybe even people who are just visiting. Perhaps it isn’t pure happenstance that Allen Ginsberg, an East Coast Jew, had his first public reading of “Howl” in San Francisco. Frank Lloyd Wright, a Midwesterner, developed a whole new style when he worked in Southern California.

If California liberated creative spirits from across the country and well beyond—surely that’s part of the story of Hollywood—Californians and their doings have also had an impact well beyond the state’s borders. There’s a vagabond aspect to culture in California—maybe a modern version of the medieval troubadours—so that certain developments in mid-20th-century San Francisco seem more closely related to developments in New York, Asheville, and Majorca than to what was going on in, say, Los Angeles. It was Isadora Duncan, a San Francisco renegade, who produced shock waves in Europe, where she helped shape modern dance and some developments in classical ballet. Another Bay Area native, Gertrude Stein, reimagined American prose from her apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris, a writer so determined to recenter the literary center that many felt she couldn’t see anything beyond herself. At least so far as Stein was concerned, she was the center—and James Joyce be damned. Who can doubt that she and her brother Leo, on their first visits to Picasso’s studio in Montmartre, were still kids from Oakland?—provincial sophisticates, much like the young Picasso.

Which is only to say that one need not remain in California to embody California’s Great Subculture. Pauline Kael, although she spent most of her career at The New Yorker, was born in California, lived and worked in the Bay Area into her forties, and is, by my reckoning, the most Californian of American critics. That independent voice of hers comes from way out West. In the introduction she wrote for the omnibus collection published toward the end of her life, Kael had this to say about her early years: “Writing from the San Francisco area, publishing in a batch of mostly obscure ‘little’ magazines, reviewing on KPFA in Berkeley, and then, in 1965, bringing out I Lost it at the Movies, I razzed the East Coast critics and their cultural domination of the country. (We in the West received the movies encumbered with stern punditry.)” That stern punditry was the official culture talking. As for Kael’s contribution to the Great Subculture, she admitted that people who didn’t like her writing weren’t entirely mistaken when they found it both “Olympian and smart-alecky”—an alliance of opposites that’s an element of what’s best about the culture of California. In her later years Kael lived in Great Barrington, a Massachusetts town with some of the bohemian nonchalance of Berkeley, where she’d begun.

I believe that all culture that matters is particular. Even the greatest masterworks—Shakespeare’s plays, Mozart’s operas—are universal in part because they’re specific.

I’ve kept these remarks in the past tense. The new century is still new. I can’t say what it will mean for artists and writers and cultural life in California—or for that matter anywhere else. The answer involves a more general question about culture and globalism, and globalism, whatever its value, encourages a dangerous homogenization. I believe that all culture that matters is particular. Even the greatest masterworks—Shakespeare’s plays, Mozart’s operas—are universal in part because they’re specific. Years ago I had lunch with Jess in the Victorian house in San Francisco he’d shared for decades with Robert Duncan. I asked him about the light bulbs in the fixture hanging over the table where we were eating in the kitchen, which had curiously shaped filaments. Jess told me that decades earlier he and Duncan had salvaged these old light bulbs from abandoned buildings in San Francisco, fascinated by their curious, antiquated designs. The work that Jess and Duncan were producing in the decades after World War II came out of a San Francisco that in the age of the internet can seem as unrecognizable as those funky old light bulbs that were still miraculously illuminating Jess’s kitchen table.

I’ve more and more come to believe that all culture that’s authentic and important somehow floats free, less encumbered by time and place than the Marxists, sociologists, and sociologizing critics and historians would have us believe. To be of a place but out-of-place is the great challenge. California’s artists and writers have known a thing or two about that. Some of the best of them, speaking with local accents, celebrating local obsessions, have found their work embraced around the country and the world.