Where Do We Go From Here?

When Mitch Landrieu, the white Mayor of the Black-majority city of New Orleans, led a push to remove four Confederate statues from city property in 2017, he could not find a local company to do the work. A contractor received death threats, and his car was firebombed.

Landrieu got the statues down. The first to be removed, that of Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard, was taken away in the middle of the night, by workers wearing bullet-proof vests and covered by sniper units on nearby rooftops. Twenty-five days later, on May 19th (coincidentally, yet interestingly, the birthday of Malcolm X) Robert E. Lee came down in broad daylight. Landrieu made an address on the occasion that was profound, powerful, and wise. But he had to send out of state to find a crane.

History shapes identity, and American identities—like all human identities—are tribal. The challenge of an enlightened modern culture is to expand the boundaries of the tribe, and sometimes that does happen. It’s been a long, slow struggle in this country to find a way of presenting history that is honest, just, and helpful—a struggle that has recently gathered momentum in the face of committed opposition.

The defenders of the Confederacy have not been easily taught, and have often insisted that they are not defending a culture of white supremacy, but rather history itself; for without these monuments, how would we know ourselves, know what formed us as a nation? The apolitical objectivity of this theory of physical history is resoundingly validated, of course, by the statues of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner and John Brown, that fill the institutional and public spaces of the American South.

Not all conservatives and not all Republicans will defend Confederate memorials. But resistance to re-examining the legacy of the Confederacy is only one particular type of denialism. Often white supremacy is defended with a slippery slope argument: let them tear down Stonewall Jackson today, and they’ll be tearing down George Washington and Christopher Columbus tomorrow.

All conservatives and all Republicans profess horror at the idea that Washington and the Founders should or could be torn down, and spit contempt for those who are complacent about the possibility. Some anti-Confederates have tried to reassure the conservatives on where we are headed. Jamelle Bouie, among others, has made the point that Washington and Jefferson are revered not because they were slaveholders, but in spite of that fact; whereas Lee is revered because he fought for slavery, and for no other reason. Bouie is rational and generous, but the fear of Washington’s demotion makes sense, in a way that those who feel this fear cannot acknowledge.

How big a leap is it, really, to go from objecting to statues of those who fought for slavery to objecting to statues of those who merely owned slaves and brutally enforced slavery, as Washington did; or who indeed established vast new systems of slavery, as Columbus did? There is as yet no national consensus on taking down Washington’s statues. But if there are occasional defacements, if there is a movement to reject the very Father of Our Nation, this is neither a surprising nor an illogical development. There remains a legitimate question: Why, after all, should a man who owned slaves be on our national currency?

There is certainly an argument that the Founders, in their wisdom if not their practices, set us on the path to being a nation of civil and human rights, if only aspirationally so. It is not wrong to be glad of that. There’s also this: slavery ended throughout the British Empire in 1838, 27 years earlier than it did in the United States. Given an enslaved American population of around 2.4 million in that year that grew to around 4 million in 1865, that 27-year gap represents something like 800,000,000,000 stolen person-hours. Stolen life-hours. Shall we expect African Americans to celebrate Washington’s victory over the British, as the price of full participation in the symbolism of our national life?

The confluence of traditional conservative fealty to exceptionalism and the darker tones of tribalism has given license to a fearful and cynical non-sequitur: those who question the legacy of the American founding hate America and want to destroy it.

What’s at stake for the conservatives is the very idea of “American Exceptionalism” (and its close cousins, the Shining City on a Hill, Manifest Destiny, the Indispensable Nation, call it what you will): the God-given, glorious specialness of a people born to freedom and led by visionaries who created a nation of singular justice, individual autonomy, and moral right. This idea is much more insidious, and much more accepted, than Confederate sentimentalism. It is far more entrenched in respectable circles. Any challenge to this idea is an existential red line for those who don’t think that America needs fundamental change, those who believe that the Civil Rights legislation of the 1960s redeemed our historical debt to slavery and that markets—if we could only let them flourish!—should be left to take care of any remaining racial barriers.

Was America successful because “our founders and their successors succeeded admirably in creating a nation in which individual freedom set the stage for unprecedented levels of human accomplishment,” as the far-right Heartland Institute would have it?

What if America is not in fact “great because she is good,” in the formulation commonly but mistakenly attributed to the French observer Alexis de Tocqueville? What if the Founders were not actually that committed to general human freedom, and the American founding and its results were less a radical, exceptional experiment in individual dignity than a grubby alliance between American colonists, who felt entitled to the freedoms of English gentlemen, and the power of the whip—in the context of the vast riches of a newly-conquered territory, extracted by forced labor, with open physical and economic spaces and thus opportunities that attracted talent and free labor from around the world? If this narrative is simplistic, it is less so than that of the “great because good” school.

If American exceptionalism is important to American conservatives, if they believe that American political validity rests upon it, it is even more an article of faith for those—led by a president who saw “very fine people” among neo-Confederates defending a Robert E. Lee memorial—who are dragging frank white supremacism more and more into the mainstream. This is where the Party of Lincoln, a party founded on opposition to slavery, finds itself today.

The confluence of traditional conservative fealty to exceptionalism and the darker tones of tribalism has given license to a fearful and cynical non-sequitur: those who question the legacy of the American founding hate America and want to destroy it. They are not idealists seeking a second founding in real freedom and meaningful equity. In the hysterical jeremiads of the right, they are communists, anarchists, Jacobins coming for you and your family. And for America.

The point of such monuments is to set history literally in stone, to deny any but the official interpretation, forever and ever.

Let’s turn now to Mount Rushmore, and to President Donald Trump’s weaponization of American Exceptionalism in the speech he gave at the monument on July 3, 2020.

In a way, Trump—who idolizes dictators and aspires to their powers—should feel right at home at Rushmore. As I’ve written elsewhere, enormous statuary is inherently intimidating, and intended to be so; Rushmore has a certain aesthetic vaguely suggestive of the oppressive piles of Socialist Realist monuments. The point of such monuments is to set history literally in stone, to deny any but the official interpretation, forever and ever.

Trump’s Rushmore speech went well beyond traditional Independence Day patriotic bromides to signal his hostility to any nuanced view of history. The speech took for granted that American Exceptionalism, in its most chauvinistic reading, is the obvious truth of America. He did not merely proclaim America the greatest country in the world, and its people the greatest people in the world; he echoed the paranoia of the radical right that any attempt to re-evaluate the public honors given to our historical leaders exemplifies “far-left fascism”; that anyone who wishes to correct an ahistorical narrative—or to remind us that certain revered leaders have less-than-admirable résumés of slave ownership and mass murder—hates this country and is part of a movement “waging a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values, and indoctrinate our children.” In an Independence Day speech, Trump caricatured and defamed significant numbers of Americans.

He also cleverly framed an implied, unspoken meaning for his followers, designed to entrap critics who remarked on it. This trap was successful. In commentary following the speech, Senator Tammy Duckworth said that Trump had used his words to honor “dead traitors”—that is, Confederates. At Rushmore, Trump did no such thing, as the radical right-wing media screamed in a multi-voiced chorus.

But Trump has defended Confederate memorials for years, and had, only a few days prior, absolutely refused to even consider renaming military bases named for Confederates, even going so far as to threaten not to sign a military spending bill if it required this. He was furious that the Defense Department banned the Confederate flag on military bases. His favorite president, Andrew Jackson—whom Trump praised in the Rushmore speech, whose memorial Trump defended—was not only a slave owner, but also the sole American president known to have personally driven a slave coffle. When Trump said “Those who seek to erase our heritage want Americans to forget our pride and our great dignity, so that we can no longer understand ourselves or America’s destiny,” his neo-Confederate supporters, the outright white supremacists, could take comfort. And were meant to do so. It is disingenuous of the far-right media to pretend not to know this.

Mount Rushmore was a good place for Trump to make the transition from defending Confederates to defending American Exceptionalism, to take a stand for an imaginary national history of freedom and justice for all. Like the statues of Confederates, slave owners, and persecutors of indigenous peoples that he defends, Rushmore is problematic.

Although officially the mountain sculpture memorializes “the foundation, preservation, and expansion of the United States of America,” its creator, Gutzon Borglum, always had grander things in mind. He wanted to tell a glorious story of the Western European heritage and its gifts to the New World. He thought that he was carving obvious truths into stone, truths that would endure unquestioned for a million years. In reflecting on the meaning of Rushmore, he wrote:

Too little has been thought—too little written, on the wide freedoms secured, the virgin worlds offered—unpeopled, untilled, ungoverned—the nomads incapable of resisting even the unorganized aggression of the invaders. No one HAS sung, painted or carved adequately the story of this irresistible God-man movement that fled its ancient moorings… following the sun into the unknown west—into the night! (Gutzon Borglum, writing in The San Francisco Examiner, 22 February 1934)

This romantic fantasy in the service of empire is many things, but it is not history.

Massacres, conquest, and racism lurk between the lines of Borglum’s published writings on the grand national and racial destiny that he created Rushmore to commemorate. They haunt the monument today.

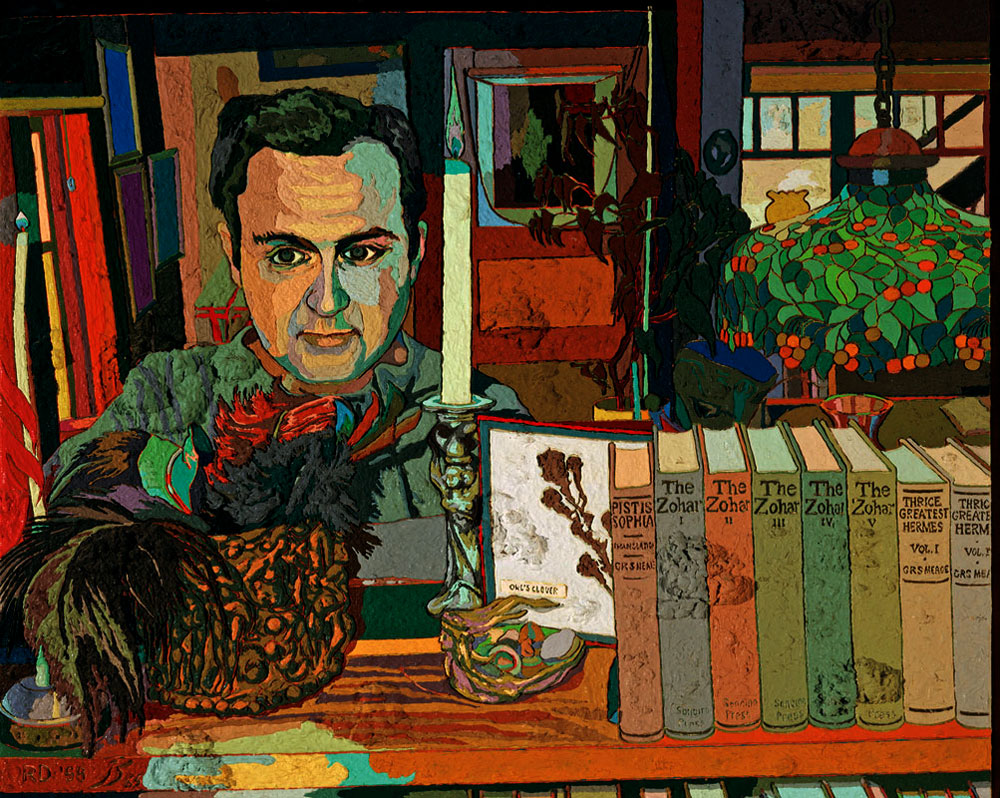

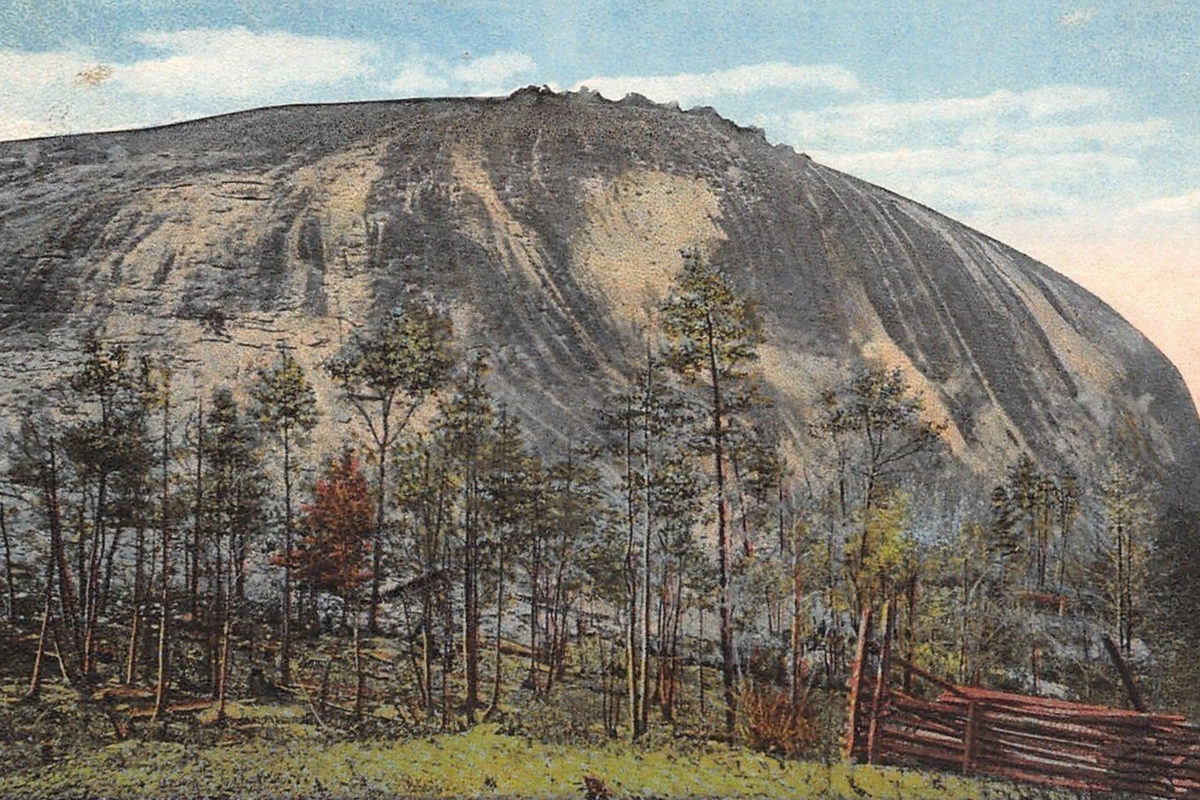

It gets worse. Borglum was a virulent racist and anti-Semite, and his belief in racial hierarchy was central to his ideas about world history—a theme he addressed in voluminous private letters, notes, and political proposals, although rarely in public. He joined the Ku Klux Klan after being recruited, in 1915, to work on the Confederate Memorial at Stone Mountain, Georgia, where the modern Klan had been re-founded that same year. He served on a Klan council—a “Kloncilium”—charged with developing a national program for the organization, a task to which he contributed many thousands of words. Although he left the Klan in 1925, after taking the wrong side in an internal power struggle, his thoughts from this period are congruent with his well-documented, lifelong beliefs. In an unpublished essay from 1923, he wrote lines that Donald Trump—with his stated preference for immigrants from Norway rather than those from “shithole countries” in Africa and the Caribbean—might well approve:

[The Nordic races] have been and continue today the pioneers of the world. They are the builders of world empire…it may safely be said that all invention, analytical science, deductive philosophy have been pushed forward… by these venturesome peoples, who have subdued savages, beautified and peopled what was in the Roman day the wilderness and is now the richest, most comfortable, best established, most sought portion of the earth… America has been peopled by these free, independent thinking races… the dark races have never moved in block or with any group conviction but always from the urge of individual misery… the oriental has no constructive initiative… it is not overstating the case that while Anglo-Saxons have themselves sinned grievously against the principle of pure nationalism by illicit slave and alien servant traffic, it has been the character of the cargo that has eaten into the very moral fiber of our race character, rather than the moral depravity of Anglo-Saxon traders… (Gutzon Borglum: “Suggestions for Immigration,” Borglum to Klan leader D.C. Stephenson, 5 September 1923; Borglum Papers, Library of Congress, Box 43)

Beyond the philosophical roots of the undertaking, there is an obvious irony in carving a sculpture popularly known as the “Shrine of Democracy” into a mountain in the Black Hills, sacred to the Lakota Sioux. The Lakota claim to the Hills had been recognized in treaties of 1851 and 1868. In 1877 the treaty of 1868 was forcibly renegotiated after gold was discovered there, and the Lakota lost the heart of their lands and were confined to dusty reservations on the plains. In 1890 a band of Lakota refugees led by Spotted Elk (Big Foot) was massacred by American soldiers at Wounded Knee—men, women, children, many chased down in the snow by soldiers on horseback as they were trying to escape the slaughter. President Benjamin Harrison awarded the Medal of Honor to twenty American soldiers who took part in the massacre, medals which have never been rescinded.

This event closed out the dispossession of the Lakota and the destruction of their power on the Plains. The American government was then regnant. South Dakota was a state of the Union, and miners were tearing up the Black Hills.

The triumphant growth of American power was part of the story of national expansion and national destiny that Borglum later carved in stone. The Lakota were not consulted on this story, and were not able to assert their own story against the power of an alien authority. Indeed, Rushmore embodies the assumption that they did not have a story worth telling.

Massacres, conquest, and racism lurk between the lines of Borglum’s published writings on the grand national and racial destiny that he created Rushmore to commemorate. They haunt the monument today. In differing ways and to differing degrees, they scar the legacy of each of the men carved on the mountain. They are an inescapable if unacknowledged part of Rushmore’s meaning, and America’s.

The single, glorious narrative of America that Borglum envisioned and Trump endorses—one that excludes those who were enslaved, conquered, and dehumanized by our national consolidation—doesn’t work today. We are seeing this now in every American city, town, and rural community, as well as in the lived experience of millions of Americans. Not before time, we are coming to understand that the only history that can be “true” in any meaningful sense is told in many different voices, recounting many different experiences.

Donald Trump resists this insight. It is inconvenient for his plans to retain power, inconvenient for the very nature and sources of the power he holds. On July 3, 2020, he stood at Mount Rushmore to defend a story that never was, and promise a future that will never be.