[drop-cap]

The friends who came to help me set up for my one-night show at the museum couldn’t keep themselves from laughing. An hour before the opening, they found me sitting on my living room floor drinking wine and watching a romcom.

I admit it was an odd image. I had put so much effort into the show: six months of studio time, crammed in before and after work, and consuming every weekend. I’d spent Thanksgiving that year at my studio, firing porcelain clay in a gas kiln to 2000o F; I’d hauled a couple of pieces I’d made in France over 5000 miles back to my home in California. And there I was, looking like an unmade bed, with wrinkled clothes and tangled hair, barely registering the ceramics all around me, which sat unpolished and unpriced.

In practice, I find waiting until the last minute to set up a show really helps with the nerves. With so much work to do and so little time, there just isn’t a lot left of you to give to the ordeal. And what I’m looking to avoid the most is valuing and pricing my work. I guess that’s why I ask for second opinions from anyone willing to give them. At the museum café where I often sold my art, there were a couple of regulars whom I knew and trusted; I’d bombard them with pricing questions about my newest pieces whenever they happened to be around. For this evening’s show, I’d reached out to a friend of a friend, a good soul whom I knew to be well-connected in the California art world. But it took the urgency of impending showtime to put her advice to work.

With fifty or so ceramic pieces, each the weight of a medium sized dog, polished and waiting to be carried into my Kia and on to the museum, my friends and I got to work. One broken piece later, we found ourselves miraculously setting up the show.

“What are you going to price this for?” asked a friend, holding up one of the larger pieces. “I don’t know, you pick,” I replied. She rolled her eyes. To me, the piece suddenly looked grotesque. How could I sell that?

Minutes before the starting time, with attendees already in the lobby, I finally rattled off three options for each piece: a “low,” a “medium,” and a “high” one. I’d let anyone who wanted to buy my work choose the price for themselves.

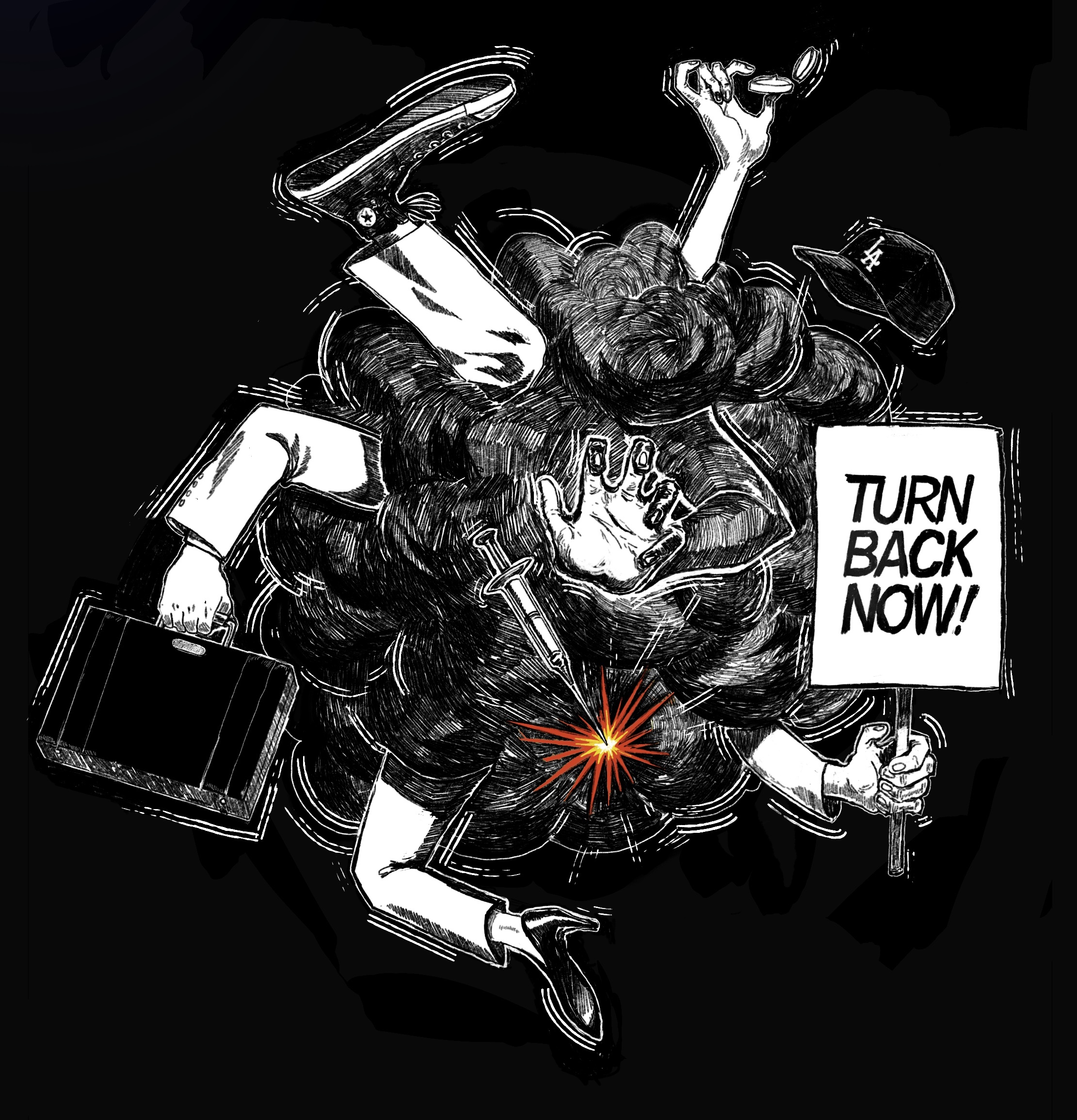

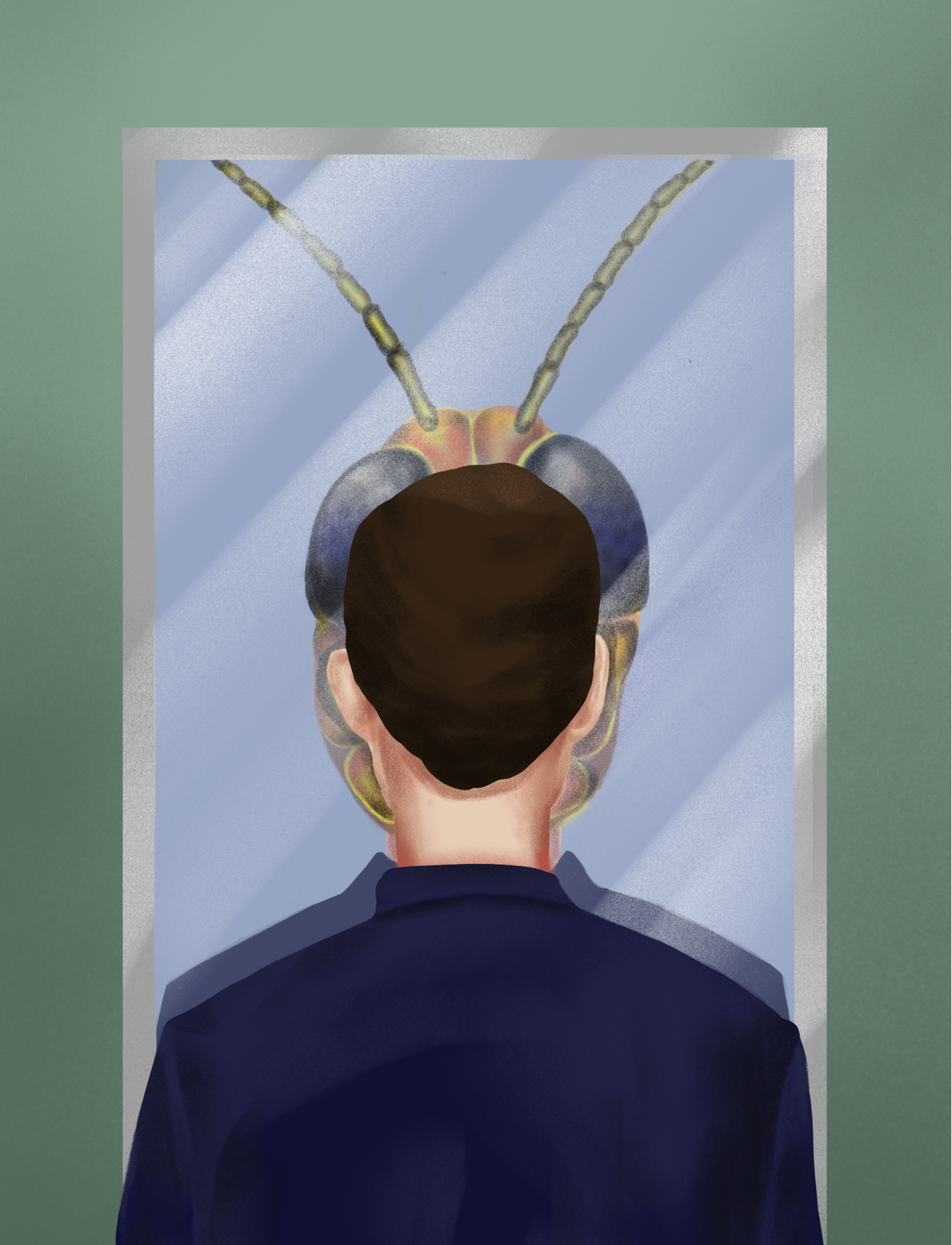

Art escapes concreteness, it eludes definition and so its essence and worth are intractably subjective, its value uncompromisingly opaque.

The process of pricing art appears simple enough. Like commodities in general, art requires certain materials and skills, all of which go into a calculus resulting in a number meant to signal value, which may or may not satisfy the artist. As with other commodities, the novelty of the artwork or its creator might play a role in its valuation, while the same can be said of familiarity and fame. Social and material trappings, also supposedly fine-tunable, often follow. Of course, this calculus is disingenuous. Art escapes concreteness, it eludes definition and so its essence and worth are intractably subjective, its value uncompromisingly opaque.

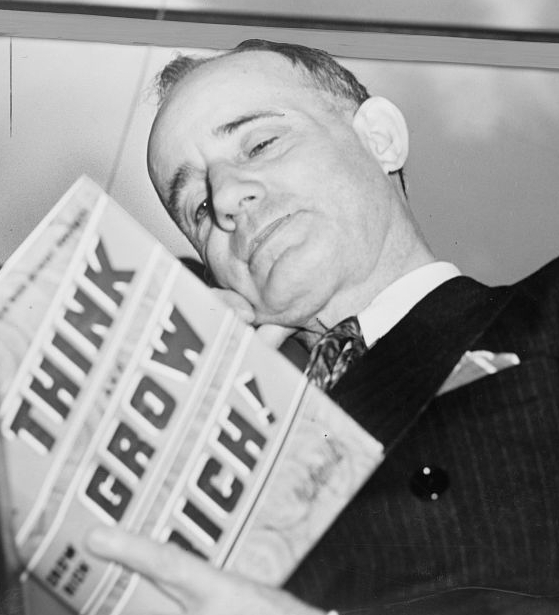

Yet “How to” guides for monetizing art abound online. The cheery author of “5 Tricks for Monetizing Your Art,” for example, advises the oversensitive artist to professionalize an exercise which is admittedly “cumbersome” and “soul-draining,” the idea being, “Well, if it's soul-draining, take the soul out of it.” Four more “tricks” follow, of which the last and most important is building an online “fan base,” which sounds like the most soul-draining aspect of all—at least for this artist.

Other creators distance themselves from the cash-nexus by hiring a “middle person.” If the artist doesn’t have to be personally involved and can avoid facing a buyer’s eyes, they can avoid all the messiness that comes with two people being in direct contact. And, of course, for the artists who can get a foot in the door, there are always art galleries. But so-called “mid-size” galleries, let alone storefront venues, have been disappearing in the US, even in artistic metropoles like New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. “A sign of the times,” said Mark Moore, a long-time art dealer, in 2016 . As for “investment-grade art,” which involves playing the long-term game in secondary markets, the numbers involved are so far outside the realm of my material sensibilities that “speculative” is the only word in that world I think I understand.

Beyond that, of course, there is always Instagram. Though I try my best to avoid it. I find the copious content supposedly tailored to “my” aesthetic stunts me. I have so little trust in my capacity not to reproduce others' work, or not to chase social media “likes” and lose my sense of self in the process. People rationalize “borrowing” others’ work as simply part of what it means to be an artist. We borrow, sure. (But not all of it…) There is something unnerving about limitless artistic content and by extension endless possibilities for reproducing, leaving little room for valuing the “creative.”

That people with familial obligations (often immigrants) tend to avoid pursuing art altogether, opting instead to pursue practical work like STEM or law, sounds like an old cliché: a type of moral obligation forged by the sacrifices their parents made to provide for their futures. This idea may seem trite in its oversimplification of diverse peoples and experiences, yet it remains powerful in its allusion to alternate livelihoods, to entire lives that could have been.

In college, I chose to major in physics on a whim; interior design was my first choice. One afternoon I told my brother. “You want to design rich suburban wives’ homes?” he asked. We lived in a modest townhouse in an Illinois suburb, having moved from Venezuela a decade prior. At sixteen, what little idea I had of American art “work” included very few professions. And my brother was right: I didn’t want to do that.

It’s not that we didn’t have “creatives” in our lives. There were aunts, uncles, and cousins who were painters, filmmakers, and musicians. Uncle Goro and Aunt Lou sustained themselves completely through their art (he as a painter, she as a ceramicist and a filmmaker). But there was also my father, who had continued living in Venezuela and had long since chosen to continue painting in the remote mountain town he seldom left. After a while, “Dad” became synonymous with the Artist, a caricature made possible by a type of limited bond formed across distant geographies.

“It sounds like you’re talking in German,” he would say of my Spanish, after we had lived apart for a decade. I’d grown accustomed to expressing myself in English with everyone but my mother. Stumbling in the only language he knows only hardened my forgetting. I was embarrassed. Ultimately our collective frustrations and misunderstandings created a chasm too deep to overcome with long-distance phone calls. So, my father remained the Artist devoted to Art.

Meanwhile, I had become disillusioned with my own creative practice; by the time I was twenty-six, I would begin a PhD in an energy-related field and almost entirely forget a time when my genes connected me to art.

When I started making art again, I wasn’t searching for it. It was the summer of 2014, a period in my life marked by a mix of intellectual monotony and existential dread (what a PhD can do to a soul). I was ripe for impulses. On a warm August afternoon, I booked a flight to France, and left the next day. It had been ten years since I’d visited my Aunt Lou and Uncle Goro at their house in the Loire Region.

Their home, an old farmhouse, had been built in the early 1900s, and Lou and Goro have been making it their own over the last two decades. They’ve kept everything they could from the family that originally built the place: from the house’s stone walls, blue wooden shutters, kitchen tiles and cement floors, to old farming equipment like saddles and pitchforks. But in the first floor bedroom, which faces a sweeping communal moor, they cut a window about three meters wide and two meters tall into one of the stone walls. The fog on the moor envelops you in the early mornings; during the day, distant cows and horses traverse in and out of view. Across the rest of the house, the items of the past still have a place, arranged anew to carry out Lou’s and Goro’s artistic vision. Their eye for aesthetics is so all-encompassing that to step into that home is to believe everything has beauty. One simply needs to attend to it, (re)imagine it, allow it in, to thrive.

There are tiny, old radios in nearly every room. Even in the back of the house, where Goro has his studio—beyond the farming equipment, worn-out wooden frames, and unattended grape vines—you can hear the radios playing France Musique, the local radio station devoted to jazz and classical music. Baroque music does wonders for rusty plows.

To create their living room, my aunt and uncle tore down a wall that had previously divided a boy’s and a girl’s bedrooms. The comically gendered palettes of the previous rooms—light blue for boy and pinkish red for girl—express new life, accented by a large, red leather couch on the blue side, and by Lou’s ceramics and Goro’s paintings scattered throughout the room. Her geometric vases and imposing bowls catch your eye immediately, popping against the colorful walls; his distressed paintings of whimsical animals and portraits reflect the house’s history, like artwork that had been there all along.

After I had time to settle in, Lou showed me her studio. It’s a small, stone-walled room that no one under five-foot-six could comfortably stand in, packed with a potter’s wheel, glazes and chemicals, and an assortment of tools. In the tight quarters, I watched her explore the delicateness and strength of porcelain clay; confident yet reverent, Lou pulled the clay to its limit, until light shined through it, and then scored its surface as it dried. When it was my turn, she hovered over me, teaching me how to keep the clay in the center of the wheel to channel its centripetal force. “Tienes que quedarte ríjida.” You have to stay firm. She hardly finished her sentence before I pushed her away. “Lo sé tía, déjame, por favor.” I know aunt, leave me please. She left. When she and Goro came home at midnight six hours later, I was still there at the wheel, in the cave-like, dusty room, with a warm, dim light hanging over me. Seeing me, Lou smiled.

My medium costs money. By my standard, lots of it. ... It’s enough to need a high-paying tech job, just to be able to quit it, and take up ceramics.

My foray into the art-selling world started about five years into my PhD program. By then I knew how to turn out bowls and cups and other vessels easily, understanding them as the kind of items whose very functionality relegated them to the status of any other commodity or artisanal work. But over time, my pottery had begun to show aesthetic cohesion. We—my work and myself—had become identifiable, I was told, and I started a website to document and picture all my pieces in one accessible, catalogable form.

One day, I showed my website to the couple who owned the café in the local art museum, after they’d asked how I’d been spending my “free” time. I felt an odd and uncomfortable pride when they wanted to buy platters from me. “How much are you selling them for?” they asked. Blushing, I said, “Nothing, I don’t want money for them.” Why would I? I wasn’t trying to make a profit. Until that point, I usually just brought my ceramics to my PhD department’s kitchen and placed them next to a piece of paper with the word “FREE” scribbled in big, childish letters.

But the owners insisted, and we agreed that instead of selling them my work, I would display, and maybe sell, my artwork in their café. That I found my stomach churning at the thought of pricing my art made me wonder why I had ever agreed to the arrangement. The obvious answer would be to make ends meet. My medium costs money. By my standard, lots of it. The more I experiment or produce, the more the bills pile up: monthly studio fees, cost of materials, electricity, gas. And then where do you store it all? It’s enough to need a high-paying tech job, just to be able to quit it, and take up ceramics.

Another, more complicated answer comes from the economic abstraction that determines value. That is, to make “good” art means to make art that can sell, that has an exchange-value.

“How’s your work going?” someone asked me recently.

“Good” … “I’ve sold out of most of my pieces” … “I sold that one for $400.”

I’m embarrassed that I’ve blurted such cringy things to people. A charitable explanation is that in an attempt to demonstrate how my pieces have been accepted and valued by others, I find myself talking about how much people are willing to pay for them. (It’s good; I can sell, okay?) These discussions are like a pernicious, slippery game of social relativity, whose players are stalking the other-world of art and value.

This game is why I think people are always asking ceramicists a version of the question, “How long does it take you to make this?” I don’t believe they really want to find out; rather, they’re trying to discover an easy translation between the time you spent on the work and the value placed on it. But I scroll through the steps, trying my best to tally up the process. “Well, there’s the creative part, which I can’t explain, and the preparation of the materials, wedging, mixing chemicals….” It’s unclear when they lose interest, but eventually they all do. And I have to confess, I don’t care, either. What business is it of theirs, anyway?

I never have these conversations with strangers who are interested in buying my art, partly because I’m not around often. When I began selling my work at the café, I avoided stopping by, afraid I’d catch someone staring at a piece, then at the price, then walking away. Anonymity shielded me from potential disappointment. But after a while, when I realized the pieces were consistently selling, I allowed myself back inside, ready to experience a different form of anonymity: for the unknown buyer, I was simply the Artist.

“You’re the artist?” a woman asked me one day. (Me? The person in a puffer jacket, sweats, and gym shoes just sipping a coffee, working on my dissertation?) “I just bought this,” she said, holding a small bowl of mine. “Your work reminds me of the paintings I’m exhibiting in the museum right now.”

I blushed and thanked her. She was an artist too.

A few months before my show, I noticed a WhatsApp message from my dad, the Artist far away in Venezuela. Before I looked at it, I imagined it must have said the usual: “Hija me haces falta. Tqm.” Daughter, I miss you. I love you. My normal reply would be similarly terse: “Yo también papá, me haces falta. Tqm.” Over the years, we’ve confined ourselves to these few words to express the challenging and inexpressible. We are so distant, after decades spent apart. I reluctantly looked down at my phone. Surprised, I read: “Me encanta tu arte.” I love your art. He went on to tell me he saw me as an artist—like himself.

I felt a sensation I had experienced the first time I saw him after a decade apart. In the six-hour car ride to see him, I was crippled by stomachaches. (Motion sickness caused by the mountainous roads, I’d thought.) But even after the car stopped, the aches were strong. And then I saw him. We looked incredibly alike; how did I completely forget? All that distance and he was a wholly recognizable person, and the pain in my stomach vanished.

The first person in the lobby outside the show was there five minutes early; many others were to follow. By 6 pm, dozens of people were flowing in, totaling more than two hundred by the night’s end. Frantic, I found myself imagining all the potential buyers: friends, colleagues, those with children, those alone. Some I knew as bosses, dominant in their fields, some as their students. Some who worked tech, some who hustled to make a living as artists. Many more whose lives I didn’t know.

I began rattling off three prices for each piece. A “low” for those on a budget, a “high” for those with so much more, and a “medium” for everyone in-between.

It might feel awkward, “cumbersome,” and “soul-draining” to have to reflect on a choice that represents my art’s value. But that's a risk I make people take, for allowing me, the artist, to keep all of me in the work—including my soul.