Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians at the Museum of the Big Bend

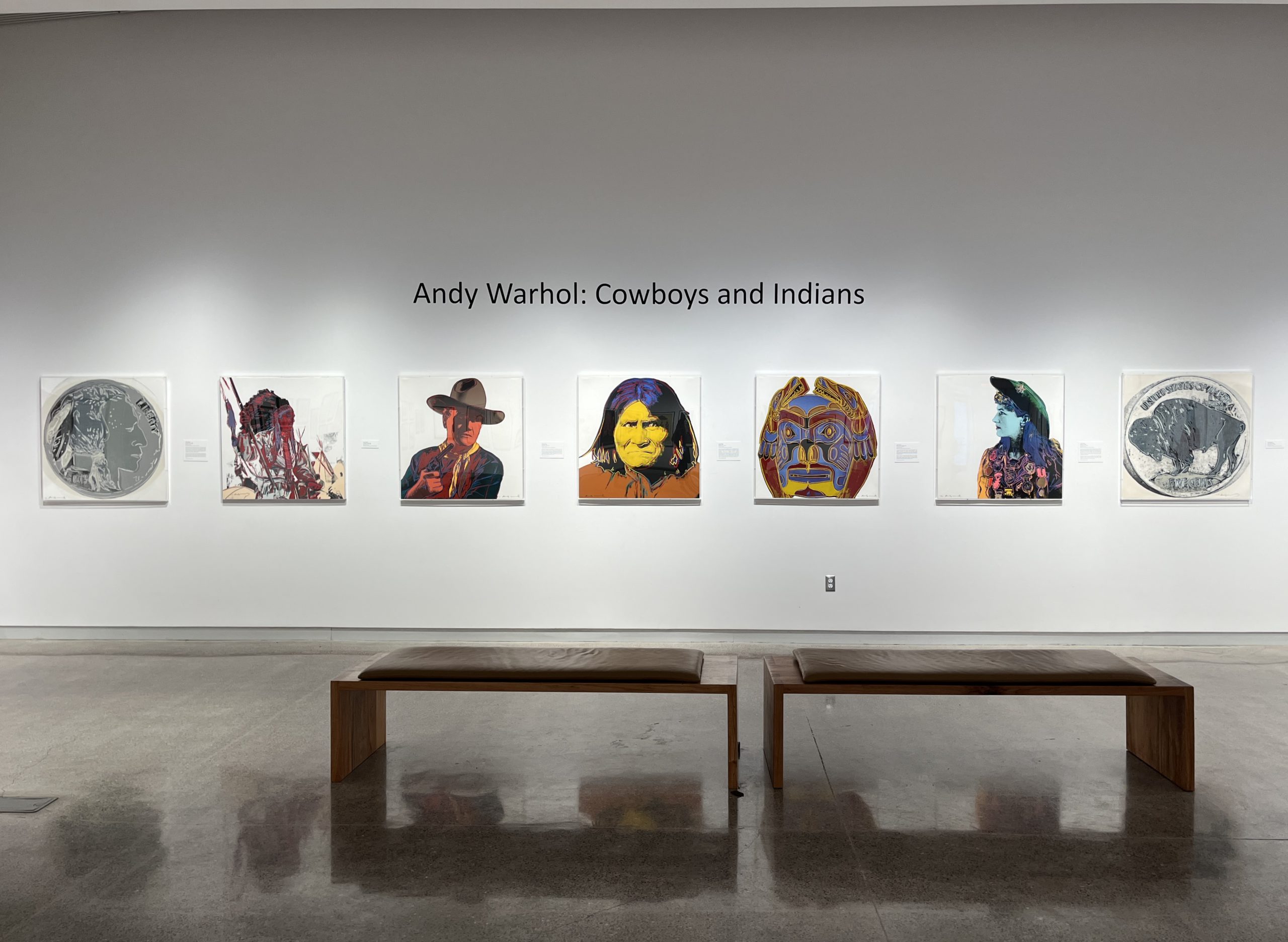

A PORTRAIT OF GERONIMO hangs next to John Wayne. John Wayne is depicted with a gun held toward the corner of the room, his body open toward Geronimo, while Geronimo faces the viewer fully, with his eyes averted to the left, away from John Wayne. Like a cowboy claustrophobia, the West closes in. The pair form a part of “Andy Warhol: Cowboys and Indians,” an exhibit hanging in the Museum of the Big Bend in Alpine, Texas. Warhol’s work, many thousands of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints associated with a particularly New York sensibility, is given a rework: Here, the fourteen prints ask, What is the West?

There’s an immediate flippancy to the fourteen prints on view, similar to Warhol’s other works, that demures from complexity. If you stare long enough, however, the complexity starts to reveal itself. Stand in front of the print of John Wayne, for example, and you might see yourself, and your preconceptions about the West, staring back at you. Warhol would never have admitted to this kind of political reorientation; he routinely denied that his work harbored any social or political commentary. “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol,” he said, “just look at the surface of my paintings and the films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” Nevertheless, his works have an uncanny ability to project the viewer, and their preconceptions about the West, back at themselves.

Warhol wore cowboy boots every day. The mythology of the West was always with him, walking him around the world all the way to Cowboys and Indians, the last series of prints he completed before his death in 1987. On the first wall of the exhibit, four prints depicting Indigenous people and objects—like a Plains Indian shield and kachina dolls—are flanked by General Custer and Teddy Roosevelt. In the gallery, as in the land, “the Indians” are surrounded—there is no escape from the so-called “heroes” of the West. These calculated juxtapositions force the viewer to re-examine the “hero” and their possible identification with him, while repositioning Native Americans at the heart of Western symbology.

On the second wall, Apache and Plains Tribes leaders are interspersed with people who symbolize the Hollywood-ification of the West, like the aforementioned Wayne and the sharp-shooter Annie Oakley. At the outer edges are Buffalo Nickel and Indian Head Nickel, which depict the transformation of Native Americans from something to be conquered, like on the first wall, to something to be commodified. The prints are all the same size with each subject positioned roughly in the center of a white background, with the exception of Annie Oakley and War Bonnet Indian, whose subjects are in profile and facing inward, toward the prints in the middle. Geronimo and John Wayne hang side by side and have similar coloration of yellow, orange and red. These are colors that evoke what we think of as the West — red plateaus, dirt and dust, the relentless glow of the sun.

John Wayne was a Western icon spoiled with Hollywood riches and Geronimo was a prisoner of war trotted out to Wild West Shows in traditional attire to appease and delight tourists. This curation cuts to the heart of the show and back to the question posed earlier: saturated with “Western” images and mythology, what even is the West? The long and storied history of Indigenous peoples or the Hollywood interpretation? Historically, Americans have a tendency to ignore real stories in favor of ready-made symbols. We are John Wayne. We are the Buffalo Nickel. We are the extraction of culture into digestible images that feel authentic, but are only vague gestures at authenticity. Or, with the luxury of looking back that the exhibition affords, we were John Wayne and Buffalo Nickel and so on. But who are “we” now?

Museum of the Big Bend, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas

What about Marfa, the little town twenty minutes west of the show? In America, Jean Baudrillard writes that “driving is a spectacular form of amnesia. Everything is to be discovered, everything to be obliterated.” The drive to Marfa takes six and a half hours from Austin. You wind through the Hill Country, slowing down at a speed-trap town every fifty or so miles, until the landscape flattens out and you can suddenly see to the horizon. Although I’ve been out to West Texas more times than I can count, every six months or so I get the irresistible itch to drive West. The first time was more than a decade ago, before I knew or cared to know who Donald Judd was. But seeing his concrete works recontextualized, for me, what Texas could be. It’s a place of extremes—extreme weather, extreme politics, extreme size. There’s extreme openness, both literally and figuratively, and extreme work. As a child, I desperately wanted to be anywhere but Texas, but that first time in Marfa, I learned that you could be a Texan and an artist.

Marfa is a place of contradictions. In one day, you might walk through kicked-up dust to get a six-dollar coffee in a renovated auto body shop, wander around Robert Irwin’s Untitled (Dawn to Dusk), hike the Davis Mountains, eat James Beard Award-winning barbecue and, if you’re lucky, meet a local who will let you ride their horse. Marfa feels like Texas, with its big skies and lethargic contentment, and that’s what people, like me, are looking for. Those places where you can grasp that slippery feeling of realness. There’s a problem here, though. Does interloping as a renegade art cowboy for a weekend bring you closer to authenticity or further away from it? For most people, Marfa is a vacation, not real life. And if you find something that feels more real than your real life, what happens when you return home? Where does living authentically end and fetishization begin?

Andy Warhol remains one of the highest grossing artists of all time. Naturally, that makes me skeptical of his ability to teach us about authenticity. Cowboys and Indians can be interpreted in at least two ways. There is the earnest view, where the images are designed to be a mirror to show us how extractive and self-serving we are (or were). We want to be authentic, but we want it to be easy, like taking a vacation. Then, there’s the skeptical approach, where Warhol was doing little more than gratifying his own fetish for the West, claiming these images—of Native Americans and Hollywood westerns—as his own while denying his work had any “political meaning,” as if symbology is fair game when divorced from politics. heather ahtone, the senior curator at the American Indian Cultural Center and Museum, says that “what is most important to take away is that the image of the American Indian has for too long been managed, controlled and constructed by non-Native people who saw the subject as a mythical, even mundane, figure and subject to exploitation as a commodity.”

The cowboy as we know him existed for thirty years, give or take. The myth and the images remain impermeable. As a Texan, I’ve been surrounded by these images my entire life. The cowboy. The Native American. The sharp-shooter. These images are borrowed or stolen or made up, based on a culture that, as a white American, is not mine. But, this is where I get stuck. Does that history make the images, or my feelings toward them, inauthentic? Does authenticity lie in the past or the future?

In Marfa today, there are a lot more people taking photos of themselves. On my Instagram feed, friends and acquaintances pose with cowboy hats and boots, sun on their face and dust-blasted buildings in the background. There are stores selling two-hundred and fifty dollar linen shirts from boutique brands out of Los Angeles. My impulse is to photograph everything. The landscape feels so real and if only I could capture that realness, then I could learn how to be, and feel, authentically Texan.

Warhol said, “Everybody has their own America, and then they have the pieces of a fantasy America that they think is out there but they can’t see.” Out West, you can see the fantasy. It’s in the barren landscape, the big sky, the dry heat, and the people who live their lives in it all. The problem with looking for the West to give you something is that it’s not yours to take.

When I left the Museum of the Big Bend, I noticed that the colors in Warhol’s prints matched the colors of the blooming desert flowers. Bright yellows, deep reds, muted purples. In all of my time going out West, I’d never caught the bloom. There were no clouds in the sky, just a perfectly blue dome resting over the agaves, the cacti, and me. But all I could think about was the last print in the series, Action Picture, completed a year before Warhol died. It’s the only print with a brown background—the rest were on white—which evokes earthiness, even a return to naturalness. Native Americans are on horseback and in the center someone holds a handgun. It’s pointed at me, as if to say, You can run, but you can’t hide.

“Andy Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians”

Ran March 1st through June 1st, 2024

Museum of the Big Bend

Sul Ross State University

Alpine, TX 79832