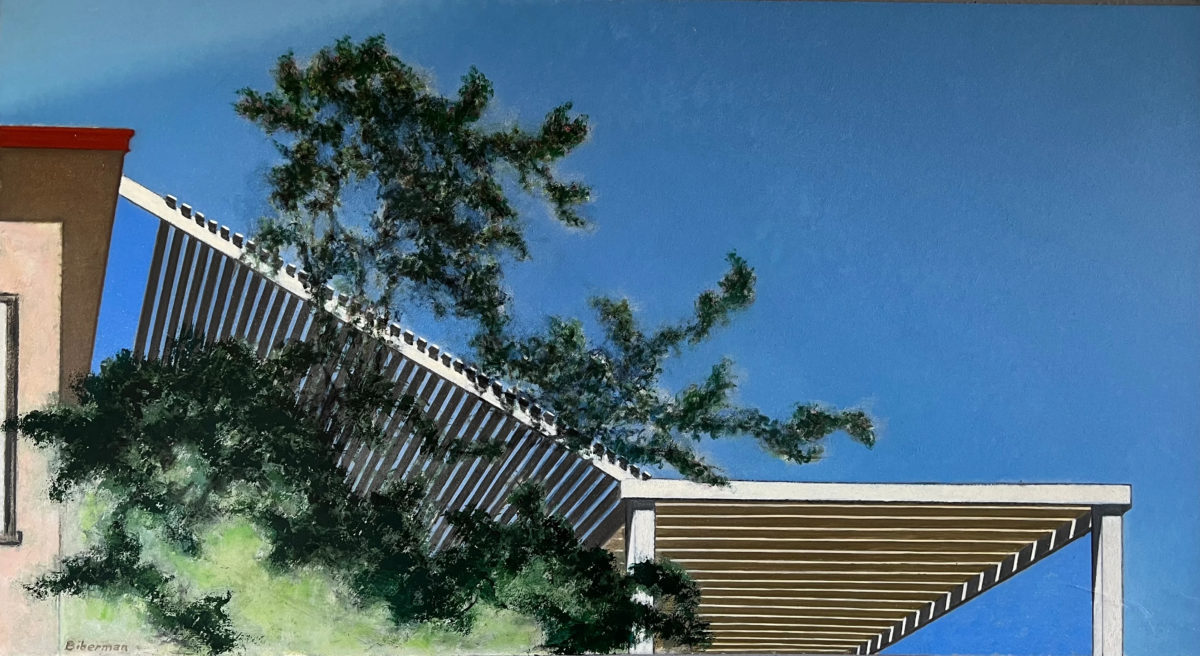

Touring “the Architectural World of Edward Biberman”

DISPATCHED BY MY EDITOR one afternoon in May to a private showing of paintings by Edward Biberman at a certain Gallery Z, I snaked my way up Benedict Canyon, awash with the vaguely Italian whites and greens and terracottas of the world above Sunset. “Gallery Z” was a mid-century house nestled somewhere high up Tower Grove Drive in Beverly Hills. In February, I caught the major Edward Hopper exhibition at the Whitney in New York that detailed—sketch by solemn sketch—the melancholy New Yorker’s journey from commercial illustrator to master of American urban alienation. From the one Biberman painting I knew, it was apparent that this Edward too understood something lurking within the very surfaces of his city.

I parked just past my destination, across from a house where disgraced Universal Studios head, “baby boss” Carl Laemmle, Jr., lived in seclusion until his death in 1979. After lingering in my car to listen to the rest of an NBA playoff game while looking out at a sun-soaked canyon, I walked back down the road to the only open door on the block, greeted by the delicate hum of a small reception. Throughout, the off-white interior wore the Bibermans like a dame inseparable from her jewels, the walls clearly accustomed to the works of masters. Pairs and small groups of people middle-aged and older took in the spare, oil-on-canvas depictions of SoCal urbanism from the foyer through the dining room to the lounge and back again. Outside, more people gathered on the terrace and in the tree-lined garden which looked out to the smoggy sprawl in the distance rising out of the earth like some sullen mirage.

As I strolled I froze at one piece, narrow and nearly four feet tall, that depicted the white wall of a four-story apartment building stained by photorealist shadows of palm trees. A familiar enough scene, and yet I was overcome with a sense of ease and unease, a feeling both encouraged and masked by the pace of daily urban life. I picked up a catalog and a price list. Matching numbers with what I’d just seen, I spotted Shadow & Substance, 1960, for a cool $65,000 (“plus applicable sales tax”). I opted instead for the small bar in the corner offering beverages gratis.

I continued along, struck by the way each painting captured subtle variations in the tenor of California’s mid-century built environment. I paused a while at Freeway Divide, another geometric mood piece from 1960. Two parallel concrete overpasses met at the center of the canvas; every one of the support columns sectioned off a windowpane-like space of blue, every pane a different shade. The whole painting was at once ecclesial and unholy. It was time to find Chris Walther, of CW Modernism, who’d put “the Architectural World of Edward Biberman” together.

Freeway Divide, 1960, oil on masonite.

Wilshire-Coronado Corner, 1938, oil on canvas.

Exchanging my empty wine glass for a bottle of imported beer, the man at the bar pointed me in Walther’s direction. He was dressed in dark blue jeans and a lightweight navy sport coat over a light-colored button-up. Chris and I exchanged pleasantries before he walked me through the exhibit. Edward Biberman, as I would soon learn, was born in Philadelphia in 1904, the son of Ukrainian Jews from Kyiv. His older brother Herbert became a screenwriter and director, and wound up going from Hollywood stalwart to Hollywood Ten. (He never recovered.) At his brother’s urging, Edward arrived in Los Angeles in 1936, already something of an innovator, following requisite stints in Paris and New York where he’d immersed himself in the explosive period and refined his artistic vision—a “unique form of modernism that mediated between abstraction and mimetic verisimilitude,” according to Walther.

We stopped to admire a few spectral works from the mid-30s: Oil Tanks/Storage Tanks, 1936, Subdivision/Mandalay Beach, 1936, and the haunting Loudspeakers, 1937. As early as 1932, “Biberman,” Walther notes in the exhibition catalog, “began an obsession with the use of floating squares, rectangles, and other geometric shapes of sometimes contrasting, sometimes complementary, colors” to define and shape space, light, and mood. Biberman’s meditative, entrancing results, we agreed, predated Rothko’s color field studies by at least 10-12 years. By removing human life altogether from his structural works, Biberman absolved the urban landscape of the burden of being, pre-ordaining a path that would soon enrapture Rothko. Through the use of color and shape and his eye for light, Biberman endowed the built environment with a spiritual quality, a hallowed interiority, and—most important of all—a sense of mystery. In Wilshire-Coronado Corner (1938), a noir for the spiritual realm, a wan and empty intersection exhibiting yesterday and tomorrow’s architecture is pregnant with choice: Down what road shall my soul roam?

As the politically charged 1930s gave way to the ambiguities of the 1940s, the moral panic of the ‘50s, and the vivid complexities of the ‘60s, Biberman’s architecturally-oriented “structural” works grew more and more precise and starkly contemplative. There is a mournful serenity to the L.A. light Biberman begins to capture in the 1950s and ‘60s, and that he masters by the ‘70s in works like 13 Windows (c. 1970s) and Esprit (1979). It seemed that, in the face of his socialist convictions, the equivocacy of mid-century American politics juxtaposed with the consumerist bent of American society forced the avowed Social realist inwards, toward a highly evolved sublimation.

Loudspeakers, 1937, oil on canvas.

Esprit, 1979, oil on masonite.

Walther moved on and I started a conversation with an older man from Philadelphia in a plaid shirt and a baseball cap. I told him the Sixers had beat the Celtics in overtime to keep their playoff hopes alive. Jack, as he was called, seemed more content to talk about L.A., particularly his own painting practice, which he conducts daily from what must be the spectacularly lit confines of his easterly 11th floor studio at the Asbury Apartments on Sixth Street. Built by Alspaugh & Russell in 1925 in the Beaux Arts-Spanish Revival style, the Asbury Apartments are a remarkable 13-story tower in L.A.’s Westlake district. By wondrous coincidence, I told him, I can see a slice of its white façade—à la Biberman—everyday from the window of my apartment, which looks up Carondelet toward Wilshire, one short block east of the aforementioned street-corner meditation from 1938.

Outside on the terrace where delicate hints of dry grass and verbena rode a languid breeze, I met Suzanne Zada, the “Z” in Gallery Z. Zada’s is a remarkable tale. A renowned art collector, she emigrated to Los Angeles from Hungary in 1957 having survived the horrors of Auschwitz. Sophisticated in that Old World manner, Zada comes across full of harbored vitality, enlivened by a transportive Hungarian accent. She has championed Biberman for over 50 years, more fervently so since his death in 1986. Jules Renard once wrote that if money doesn’t make you happy, then try giving it back. But in Los Angeles, survival was a badge best worn rich, and these hills of chaparral, oatgrass, and deluxe property values seemed to exist only to offer ephemeral tributes—sometimes even deserved—to mortality interrupted.

The spring afternoon idled away and I itched to descend, back into the web. I wondered if paintings are only alive the minute they are completed, their paint still wet, the rest a sort of radioactive decay? I don’t know why I thought this. All this wealth and death and polite conversation. It was time to leave. The 124 Spider I’d borrowed to meet the day started to life with a throaty growl. Down I sped, from the rarified realm of the hills back into the spindly sequences of anonymous city blocks Biberman did so well to illuminate.