It’s worth starting off by saying that I’ve been part of the problem. I’ve moved to cities without any intention of staying. I’ve hopped from neighborhood to neighborhood without caring what impact my presence had there because, as far as I was concerned, my presence was temporary. I moved to Seattle, then New York, then San Francisco, chasing opportunity each time. I would know it was time to move on when I saw neighborhood staples being replaced by bland and sterilized chains. I only shun the label “gentrifier” because I wasn’t gentry. I didn’t bring the coffee shops and record stores, I didn’t bring much of anything really aside from a certain shade of anxiety that almost inevitably comes with something or someone new appearing on your street.

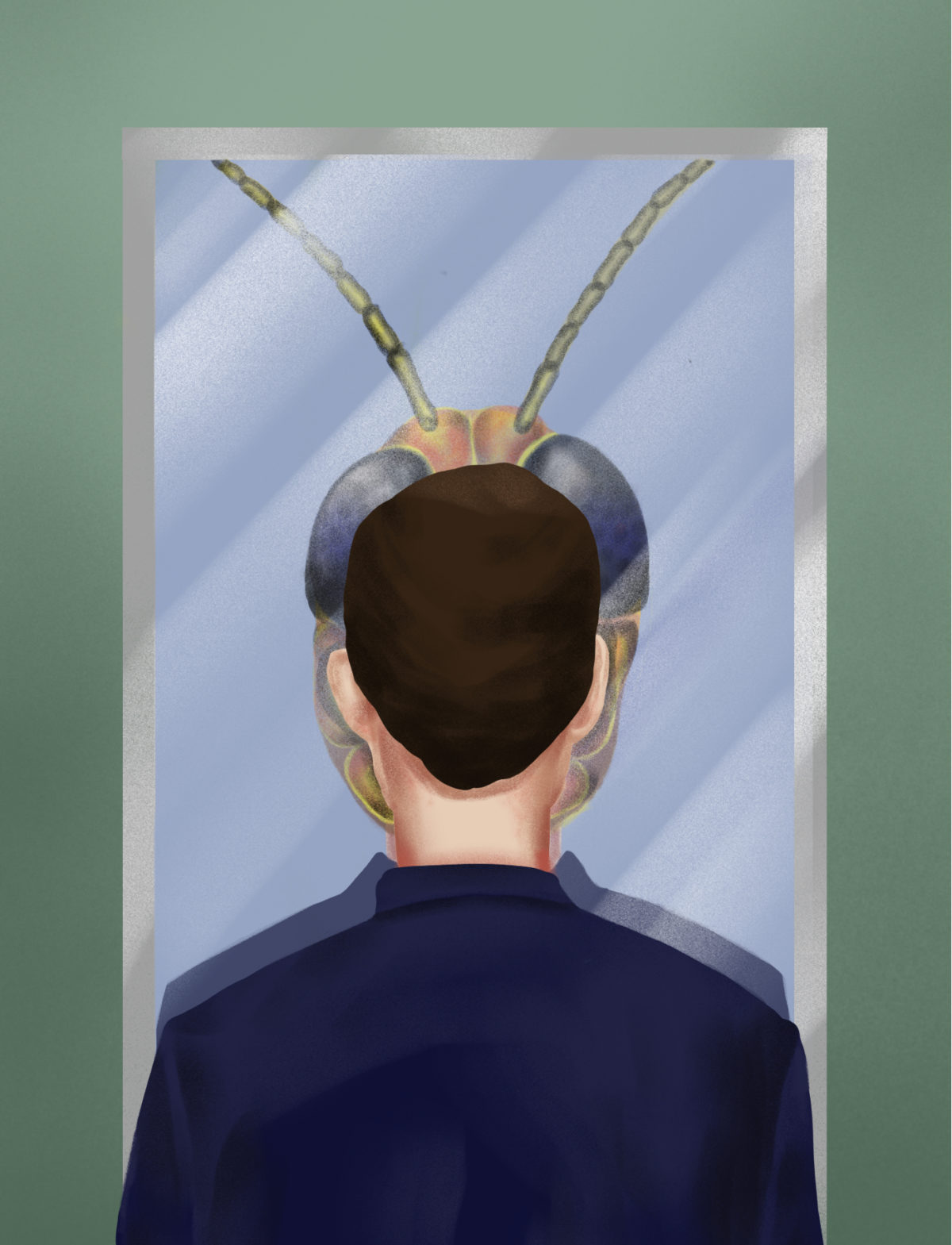

Of course, just because I didn’t personally swap out the type of snacks in the bodega doesn’t shift blame off of me, I was the one being catered to as I switched neighborhoods again and again in search of cheaper rent. That’s the one thing I always used to assuage my guilt: I was just moving to these places to avoid spending half of my income on a terrible apartment. Sure, I didn’t have much in common with the existing residents but what else was I supposed to do? I didn’t recognize at the time that this mindset of inevitability had been taken up by a substantial portion of my generation. We’re far from the first to dabble in affluent transience (we are largely the children of Yuppies after all) but we do seem to be perfecting the form to ever more deleterious effects. We are the locust class, rootless migrants in our own country.

The locust class is stuck miming the behavior of the elite, affecting an aspirational cosmopolitanism in the process.

Is it wrong for us to chase opportunities, to seek out our fulfillment in the location of our choosing? Almost certainly yes. It’s the burden of manifest destiny in a time when we understand the consequences of boundless expansion. I recently put a couple hundred pounds of carbon into the atmosphere to end up in a place with cleaner air. Did I realize my own hypocrisy as it was happening? Of course not. It’s often only possible to see ourselves through reflection and in this instance it took the form of a funhouse mirror: watching on my phone as the true gentry escaped the pandemic on their yachts, waited out social unrest from their fallow country estates, and fled wildfires on private planes. If their crimes are worse than mine, it’s only due to my lack of means.

The locust class is stuck miming the behavior of the elite, affecting an aspirational cosmopolitanism in the process. In an earlier era the fortunes of the American bourgeoisie were anchored to a place and so they acted as civic boosters with their middle class counterparts following suit. One side created an opera house or a baseball team and the other became ardent fans. Whole books, good ones, have been written on the factors that have divested American elites from their sense of civic responsibility but an undeniably outsized impact of this phenomenon is the diminishing loyalty that the middle class hold for their cities in turn. A few thousand wealthy people moving around may or may not cause any issues but a few million dislodged, merely affluent folks can become a tide.

The demographic term for the locust class is “Temporary Urbanists.” We’re folks who move to cities in our early 20s and leave by our early 30s, typically heading to calmer parts of the same metro area (read suburbs), smaller cities or towns, and almost never back to where we came from. That there are millions of us (3.6 million at any given time according to economist Stephen D. Whitaker of the Federal Reserve Bank) comes as no surprise because we’re so highly visible. Filling cafes, spilling out of bars, piling into Ubers, and loudly complaining about local customs, we are the antithesis of what the term “Urbanist” has traditionally meant: an expert of and advocate for cities. Members of the locust class don’t stay long enough to cultivate expertise and only advocate for cities after they’ve left, hoping that the consumable parts are clean and frictionless should they ever want to visit. We are long-form tourists role-playing as city dwellers. The recent tragicomedy has been city governments falling over themselves to attract us and the corporations that employ us. While we add to the tax base during our stay, the presence of so many untethered people can’t help but loosen the social fabric. Unfortunately, the issue isn’t as simple as addressing the lack of attachment to our new homes. We also have to understand the missing connection to wherever we started out.

I inherited this lifestyle. I sound like I’m shifting blame again but searching for the causes of your bad behavior usually does. My parents didn’t raise me anywhere near where they grew up and neither did their parents. As complicated and uniquely tangential as the stories of my recent ancestors may be, the bullet points (The Great Depression, The New Deal, World War II, suburbanization) are all narratively familiar to us as the forces that created and mobilized the American middle class in the 20th century. Mobilized being the operative word. Between 1940 and 1947 alone almost a quarter of the US population switched counties or states at least once. This wasn’t a nationwide game of musical chairs though. Tens of millions were leaving small communities and flooding cities as indicated by the fact that, according to census data, 40% of the country lived in urban areas at the start of the century compared to 80% at the end. Entirely new urban areas were being created since existing cities could only expand to accomodate so many.

I think it’s this misunderstanding that defines the locust class: That the things that make a city, or any living space, good are meant to be consumed rather than produced. Taken from rather than given to. It’s an extractive and unsustainable logic at the personal level that’s creating unlivably homogenous cities when brought to scale.

Then as now, this was largely attributed to people seeking economic gains. Shifting industry and restrictive immigration policies forced wages up so drastically that in 1949 an uneducated male worker from the rural South could expect to earn 30-70% more by relocating to a city. Can we really blame people for moving when it meant the difference between poverty and stability? Or to put it another way, who would you be willing to crowd out for a 70% wage increase? This conflation of geographic mobility with social and economic achievement appears as a dark and near constant American throughline back to the colonial period. To find your fortune you had to go elsewhere and it didn’t particularly matter who was there before you. But what kind of fortune are we trying to find?

Money may explain the initial drive toward American urbanization but it isn’t the only motive of the locust class. While cheap rents shuffled me around within cities, it wasn’t increased wages that drew me to them in the first place. I probably could have gotten a fine job in my hometown (a small city at 250,000 inhabitants) along with a significantly lower cost of living. It was the amorphous and ever-alluring promise of “opportunity” that I fell for—the idea that cities contained some sort of limitless source of culture, savvy, and authenticity that you could consume in order to attain a higher state of being rather than having to produce it yourself. More than any other thing, I think it’s this misunderstanding that defines the locust class: That the things that make a city, or any living space, good are meant to be consumed rather than produced. Taken from rather than given to. It’s an extractive and unsustainable logic at the personal level that’s creating unlivably homogenous cities when brought to scale. I’ve watched neighborhoods transform around me, almost seeming to fit my image, but without my having had an active hand in it. The outcome chased me away again and again. Why? Because when we’re catered to, we aren’t given a chance to find what it is that we really want, we just get greater efficiency and “good enough.” We don’t end up with a stake in the outcome and without that tether, we just move on to the next place that has some character left to absorb. And it seems like we may be running out of those places.

A nauseating amount has been written about the death of cities as a result of the pandemic. Whether citing the proliferation of remote work or hygienic concerns, it seems that people can’t wait to toll the bell and proclaim that urban areas are emptying. Cities may very well die but it won’t be from people leaving in 2020. For every article or anecdote about booming ski towns or U-Haul rental rates there’s a counterexample with hard numbers. The Consumer Credit Panel and the United States Postal Service have both produced huge data sets showing a mostly normal outflow of people from major american cities, not a frantic mass exodus. What they also show though is a significant drop in the number of newcomers especially among (you guessed it) well-off young adults. Since last March there has been measurable reluctance on their part to relocate to cities. I doubt it’s much more than a blip and I’d be embellishing to call it the end of the locust class, but why shouldn’t it be?

After all, the locust class isn’t so much a group of individuals, as much as it is an extractive mindset. A temporary interruption of the cycle can force people to consider why they wanted to move in the first place. I’m left thinking that people with the means to move comfortably shouldn’t move at all, and people forced into migration should be afforded hospitality. It can’t possibly be as simple as that, yet moral suasion could go a long way. Where’s the threshold of acceptability? Are social or economic opportunity reason enough to move? And more importantly, what responsibility do we have toward wherever we end up?

For my part I’ve decided to just stay put. I was sick of living in rootless cities with rootless people, a situation that made San Francisco nearly unbearable until I realized my own solution. I couldn’t seek out genuine and authentic places to land when this one ran dry because the very act of ending up there would have made them disappear. I had to recognize where I was for what it was and see how I fit in, as a participant rather than a colonizer.