Reminiscences and remembrances of a handful of postwar literary figures

Pour Fripouna

For the old know everything—including all the secrets of the young.

—Gary Indiana

I SPOKE FRENCH WITH MY MOTHER, performed in plays with my father, played the piano, listened to Beethoven and Verdi, and though the good people of eastern North Carolina are generally friendly and warm-hearted, they unsurprisingly made me feel like a foreigner every single day of the twenty years I lived among them. All I ever knew was anomie. Social distancing began for me in kindergarten.

My violently eccentric parents soon convinced me that my future lay in classical piano. I was going to win competitions, make records, perform all over the world. After all, I played better than anyone else my age in the region, so who could say otherwise?

By the age of twenty-one, my piano dreams having gone up in smoke, I was sure of only two things:

1) I loved books more than anything.

2) I wanted to move to Paris.

And this I did, on September 2, 1989.

Once here, my intransigence, provincial ignorance, and social awkwardness made it hard for me to get along with most of my peers, but I was eager to learn all there was to know about the world of books, and find a way to forge my way into it. The only question was: how?

Ten years passed.

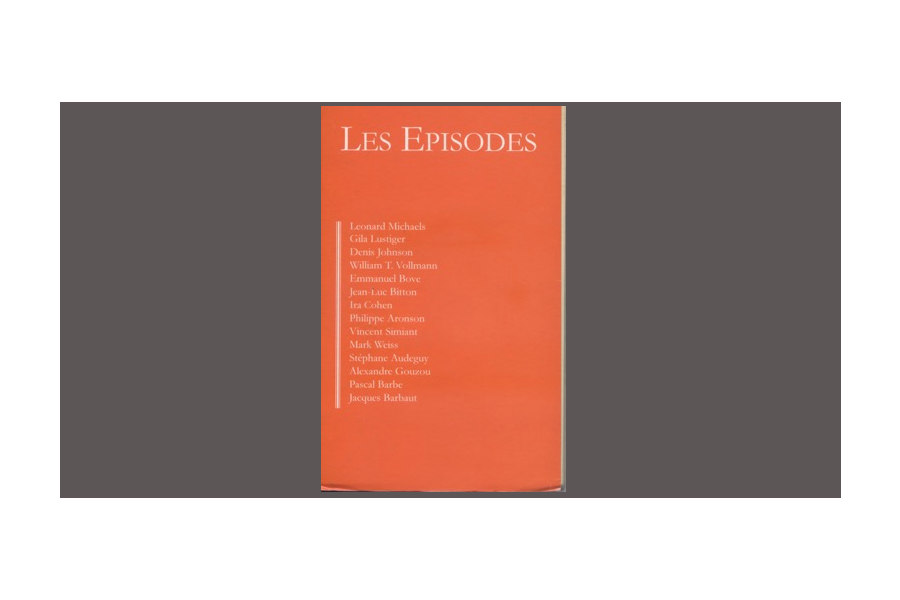

I taught piano, I taught English, I studied translation, I found myself involved with a literary magazine, Les Épisodes. I also became more sociable.

At one of our launch parties a young woman I knew, remarking on how relaxed I seemed around older folks, fixed me with a violet stare. Look here, she said, every family has fathers, brothers, uncles, lovers, grandmas, grandpas, bubbies, zubbies… You—you are the son. Destined always to filial duty.

Pinned and wriggling on the wall, what could I say to that?

I have always tended to look first to the past in music, art, and literature. When in early 2001 my French friend Max (not his real name) named me co-editor of Les Épisodes, I was deep into American literature of the 1960s and ‘70s. It dawned on me that I now had a perfect excuse to contact some of the writers from that time I was interested in—the alte kackers! The brilliant still alive oldsters!

The first name on my list was Leonard Michaels (1933-2003).

The second was Irving Rosenthal (1930-2022).

Both were robustly American and more than a little wacky, with a wild, sexy, brutal humor, Yiddish rhythms crackling beneath the impeccable English prose. LM’s Shuffle, and IR’s Sheeper gave me goose-bumps, blew air through my hair (I had oodles of hair then), made me rejoice in language, gave me hope.

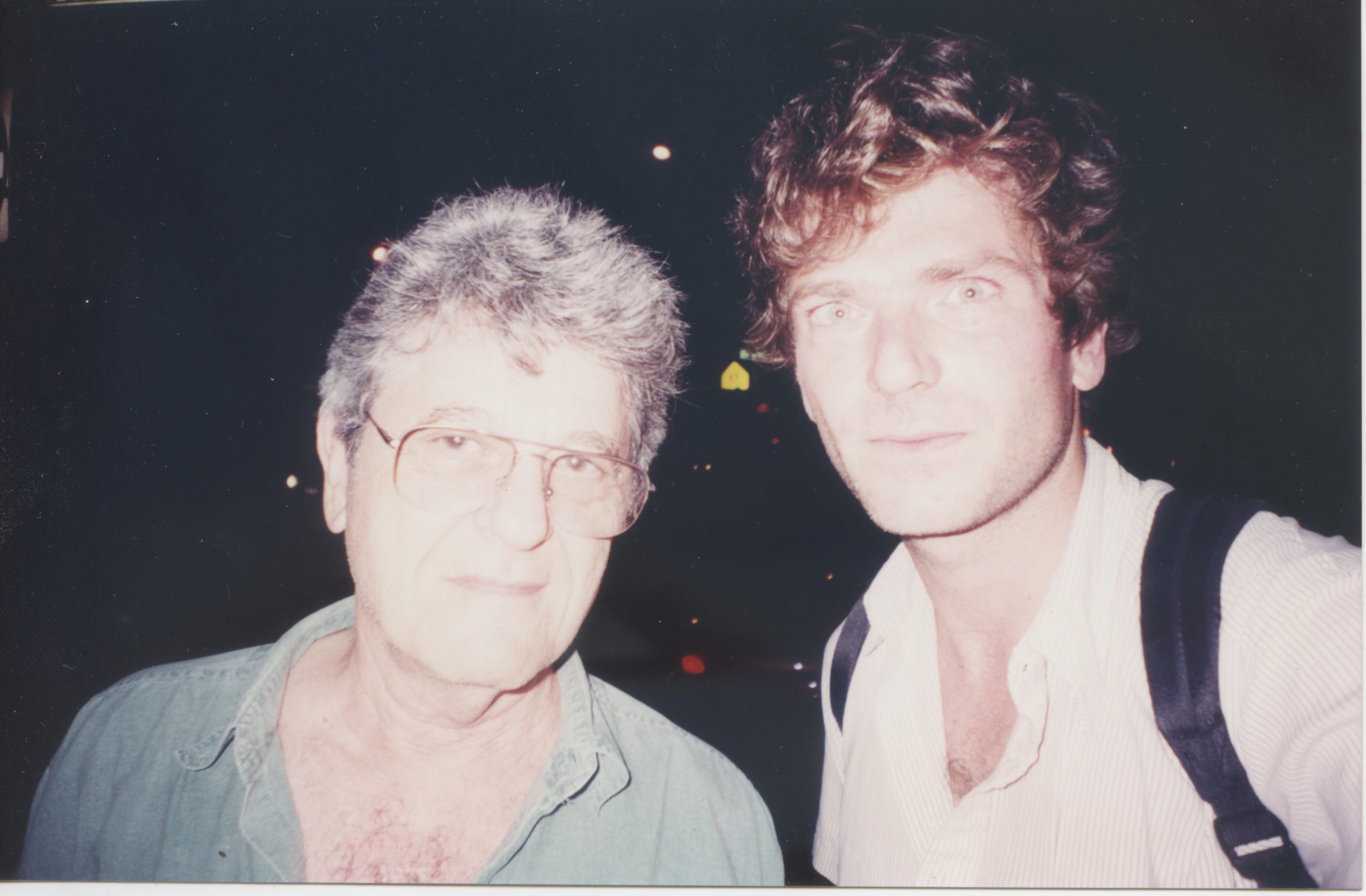

Michaels was bouncing around between Italy and the Bay Area and I found him rather easily.

Rosenthal was reclusive. But I soon reached him through poet, photographer, and master shoplifter Ira Cohen (1935-2011).

Though Ira was about as conspicuous as they come—rotund and bearded, a rundown beatnik Jewish Santa with tattoos, beads, necklaces, and, at times, a Spiderman mask—he had the knack, when he needed to go shopping, of becoming invisible. The French writer who put me in touch with Ira told me she saw him once stride into a supermarket grinning broadly and walk out with a turkey, a carton of milk, and three loaves of bread, without paying. And nobody said a word.

Max and I flew to NYC in August, 2001 to hang out with Ira and Lenny (as I now called Leonard Michaels) and plan the next issue of Les Épisodes. After Max and I visited Ira in his Midtown apartment he came downstairs with us to the CVS Pharmacy, whence we witnessed him make off brazenly with Scotch tape, Brillo pads, and bananas. The only thing he paid for was a pack of cigarettes, because cigarettes were over the counter.

A few hours later, walking the streets with Lenny, I was struck by his strut, shoulders back, chest forward, his cock-of-the-walk here-I-am stride and swagger, his NYC pride and confidence… on the balls of his feet like a dancer.

Before I ever dreamed of meeting Lenny, my self-styled fierce friend and fellow American expat in Paris Hubert Blair (not his real name) told me that one of his California friends had told him that Leonard Michaels has a lightning bolt design in the floor of his kitchen in Berkeley, symbolizing his anger.

That lightning bolt blew Hubert and me away. I remember us grinning at each other, shaking our heads.

At the time and for a long time after I thought my own anger would buoy me on my dash toward literary relevance. I thought being neurotic was cool, useful, a tool.

Now my idol was bitter about being largely forgotten. I admired Lenny a hundred—a thousand, a million—times more than other writers of his generation who were recognized everywhere as geniuses, but I knew next to nothing then about the fickle business of literary reputations and the havoc it wreaks on egos. So when Lenny told me about having dinner once in London with Harold Pinter and not feeling intimidated and I asked him why he should have felt intimidated and he said, Well, you know, Harold Fucking Pinter! I countered with, Well yeah, but Leonard Fucking Michaels!

Max joined us at the Zebulon, a bar on East Broadway where a white dude played 1920s blues songs on acoustic guitar. A fist-sized black fish swam around in a tall tank next to the bar. Lenny and I drank beers and told each other filthy jokes (telling filthy jokes being one of my specialties—as it turned out, it was one of Lenny’s specialties, too. And by filthy I mean absolutely unprintable here).

Pushing seventy, Lenny had a full head of hair and looked youthful. I rolled a cigarette for him. You’re killing me, he said, smoking. We laughed. Lenny signed and inscribed my copy of Shuffle on the bar:

To Philippe, my future editor and translator, Lenny, NYC 2001.

I never saw Lenny again. We planned to meet in Paris, but when he finally made it here I was visiting my parents in the States.

On the other hand, I introduced Lenny to Hubert Blair, who had recently moved to Rome, and they became fast friends.

Lenny and I had regular email exchanges that resembled actual letters. He sent me pages of Ginny, an “extreme novel” he was working on about a high- school girl. I met with Parisian publishers to talk about getting Lenny’s work back into print in French, and Lenny wrote asking me if I had any business sense and did I want to be his agent. Some friends of his were interested in founding a publishing venture with the goal of publishing his book… I really don’t want to waste time, Lenny wrote. If this becomes serious, let’s be serious. You will have to wear a shirt and tie and not seem to be enjoying life so much.

It did not become serious, but we had a good time. Lenny was unguarded and charming in our exchanges. He was clearly eager to claw his way back to literary relevance. Why not in France?

I was amazed to be on such intimate terms with my distressed hero. I was going to save him if I could.

When Lenny got sick Hubert called and said he thought he would pull through. Wishful thinking, that was. It seemed like one minute Lenny was sick and the next he had joined the ancestors.

My grief at his passing was disproportionate; I hardly knew him. But I loved him.

My grief at his passing was disproportionate; I hardly knew him. But I loved him.

Hubert Blair had a rower’s build, a Dick Tracy jawline, and an extraordinary literary sensibility. Everyone who ever met him was shocked that he had not yet committed to paper the electrifying masterpiece he was obviously carrying within him. We first bonded over our shared admiration for Lenny. Though only a handful of years older than me, Hubert became my mentor, encouraging me to read David Foster Wallace, William Gass, William Gaddis, Jack Black (whose You Can’t Win stands on my bookshelf next to How You Lose, another prison masterpiece Hubert told me about), Gilbert Sorrentino, Denis Johnson, Carl Van Vechten, Irving Rosenthal, Robert Coover, Guy Davenport, William Bronk, William S. Wilson… Hubert loved to talk about writing, saying for example you have to make every word do the work. Once, after taking apart one of my stories, Hubert shook his head. I was now left, he said, with the intractable problem of language, which sounds impressive though I’m still not sure I know what it means. Hubert had hosts of literary, artistic, exiled political oddball friends of all nationalities, including the writer who calls himself Evan Dara, and he introduced me to all of them. Sadly, my immaturity, impulsiveness, and growing success at meeting, befriending and publishing authors he admired coupled with Hubert’s all-consuming self-loathing and neuroticism (not to mention a dad- shaped hole in his psyche that put mine to shame) conspired to snuff out our friendship shortly after Lenny died.

A week after first speaking with Ira on the phone, I received from him a fat colorfully-stamped envelope containing Licking the Skull, a “retrospectacle” on glossy paper of Ira’s photographic works in color and black and white published by NYC gallery owner Cynthia Broan, including one in color of an Indian gentleman in a beige cap cradling a human skull to his cheek, stuck-out tongue ready to lick it.

Ira’s parents, like Lenny’s, like Irving’s, were immigrants from eastern Europe—with the added twist that Ira’s were both deaf. Ira’s first language was sign language. Once when Ira was a toddler he knocked over a boiling pot of water and scalded himself and screamed but his parents couldn’t hear him.

And here you are, all these years later, still screaming, I said to Ira on the phone.

Very funny, Ira rasped. It was through Ira that I met poet Edward Field (1924-), and through Ed, a few years later, editor and essayist Ted Solotaroff (1928-2008), who lived part of the year in Paris.

Ira met Irving in 1963 in Tangier, where Ira, using money from an inheritance, launched the magazine Gnaoua in which excerpts from Sheeper appeared for the first time. Irving, critic and novelist Alfred Chester, and novelist Charles Wright lived briefly together with Ira and his wife Rosalind in what was dubbed the “bat palace” after Rosalind one night butchered and cooked a bat they all ate a piece of. According to Ira, Irving asked to eat the penis (he said it tasted like gefilte fish, Chester wrote to his friend Ed Field in New York).

Irving was an elfin man with a gigantic ego. Ira said that he picked Irving up once and he felt as heavy as a sack of onions. At first my relationship with him was hunky dory. He was eager to share his stories, and would coo that he never minded being interrupted by me when I called him to chat and hear about what he was reading and doing. When I asked Irving about Alfred Chester he said that Alfred had sent him The Exquisite Corpse signed with an inscription and Irving had ripped out the autograph to keep and thrown away the book. He also told me once that the young men who came to his commune were free of drugs and women, which made things a lot easier, as if loving women were as dangerous to one’s health as mainlining heroin (perhaps unsurprisingly, Irving once wrote, homo sex is the only realistic solution to the world’s population problem).

Uncannily like my mother (with whom he shared an October 9 birthday), Irving would get upset with me at fairly regular intervals, over a trifle, and then “punish” me by interrupting all interaction for a given time. So I would end up writing an email to apologize for the clouds hovering above our heads, hoping my words would manage to disperse them.

Irving is autocratic, Ira said. He’s antihuman. He’s such a shit.

Ed Field’s longtime companion Neil Derrick was blind, and it was humbling over the years for Emma and me to walk the streets of Paris, London, and New York with them, watching Ed lead the way with Neil’s hand on his shoulder. Curb coming up, Ed would say. OK. Step. They had it down tight. Rarely did they break stride.

Ed and Neil were lean and fit, and though Ed was primarily a poet, he and Neil wrote gay porn and historical novels together.

The first time we met Ed and Neil in Paris they were keen on discussing the zippers on the trousers of the French riot police (the CRS as they are known in French).

What about their zippers? I said.

It turned out, Ed explained, smiling with relish, his jet-black eyes narrowing to slits, that whereas normally a fly unzips from top to bottom, the CRS fellows had flies that unzipped from bottom to top. Why was that?

I said I didn’t know what he was talking about.

You never noticed? Ed said, arching his eyebrows, surprised I didn’t share his penchant for crotch watching.

Ted Solotaroff had four sons and a tendency to consider any man under forty as fair filial game. It’s like having another son around, Ted said about me not long after we met.

Ted had sad dog eyes that occasionally flashed with passion. He would at regular intervals drum with his hands on his knees or thighs, pensive, mouth open, looking alarmingly like a fish out of water.

Intrigued by my bilingualism, he asked if I read French writers from a French perspective, and American writers from an American one. I said that I did and Ted suggested I write an essay about bilingualism. I said I didn’t think I knew what to say about bilingualism or how it worked—that I only knew the two languages were wholly separate and whole in my mind—and he quoted Alfred Kazin, who when asked one day what he was going to write about, answered:

I don’t know; I haven’t spoken with my typewriter yet.

Ted smiled. Trust the writing process, he said.

Irving had planted a pernicious spidery seed in me: the belief that a writer should write from within the parliament of writers, showing writers what you could do in order hopefully to surpass them.

That sounds like a perfect recipe for writer’s block, Ted said. He shook his head. You know, when you write, you just have to walk out to the mound and start pitching.

When I asked Ted about Lenny he said Lenny’s writing was violent. Very terse stories. No fat on that animal.

When I asked him about Tobias Wolff, Ted said Toby’s writing was like a mountain stream: dip in anywhere—he dropped his hand to his side—and you can feel the current.

Harry Mathews (1930-2017) was another writer on Hubert Blair’s radar, the kind of writer Hubert said was marginal—though major in the margins.

One day I came across a lovely little book by HM, called The Orchard, a remembrance of his friendship with French writer Georges Perec, whose death in 1982 from lung cancer at the age of forty-six, came, HM wrote, as a scarcely credible shock.

In deceptively simple prose, and borrowing Joe Brainard’s I remember technique, HM reveals in a few dozen tableaux his deep love for his departed friend by remembering GP’s fondness for TV and radio jingles, and disposable Wilkinson razors, and cartoons, and restaurants, and waiters; his sneezing fits and beautiful green gray eyes; and taking GP to the elementary school in Villard-de-Lans where GP had been hidden—and even baptized under an assumed name—during the Occupation and the director asking GP if he were related to GP, and GP saying: But I am GP!

HM lived in Paris part of the year. I looked him up and called the number. A man’s voice answered.

Monsieur Mathews? I said.

Lui-même, HM replied in a voice of velvet.

I stammered a few words about his gorgeous pages on GP, and his hilarious novel, My Life in CIA, which I had recently read and loved, and he invited me to have lunch with him the next day at Les Fins gourmets, a small bistro on Boulevard St- Germain.

Tall, barrel-chested yet frail looking, HM wore a green shirt, green pants and a sleeveless vest full of pockets out of one of which spilled a white plastic bag. He greeted me as an old friend.

We chose an outside table under the protective sprawl of the restaurant’s green awning. First Harry wanted to know what kind of wine I wanted to drink. I said whatever he wanted to drink. Then he asked:

Do you smoke?

I had quit smoking cigarettes a few years back, but still reserved the right to smoke a few on occasion. But no, I didn’t have any cigarettes on me, I told him.

When the waiter came to our table he greeted HM warmly—Bonjour Monsieur Matty-ooze!—and Harry, shaking his hand, smiled and said:

Please bring me my boîte.

Of course, Monsieur, the waiter said and disappeared back inside the restaurant. He soon returned with a large, yellow metal box, which he placed on the table. Looking at Harry, with an elaborate flourish he opened the box.

It was chockfull of Dunhills.

Merci, mon cher, Harry said, and looking at me, pointed at the contents of the box.

I produced a green plastic lighter, and we smoked.

Harry had massive hands and huge thumbs—the hands of a butcher or a violinist, I thought.

The Orchard was extremely painful to write, Harry said. Throughout our conversation he spoke freely of his other books (mainly CIA and The Journalist) but every time I steered him back to The Orchard he would get a pained, pinched look on his face and change the subject.

Later in the week when I told my used bookseller friend Jim that I had had lunch with Harry Mathews, he said:

Who?

For the longest time whenever Lenny came up it wasn’t Bernstein or Cohen or Da Vinci or DiCaprio I was referring to, but Leonard Fucking Michaels.

However, the years have stacked up since his death, and my parents are dead and all these old men (save Ed) are also dead and I am now a dad. And Emma and I named our son Leonard. So whenever I say Lenny nowadays I usually mean Leonard Aronson, who was born in 2016.

The other day I was talking to Emma about this essay, and I mentioned Lenny (Michaels) and our boy said:

What?

So I guess the violet-eyed lass was wrong. I was destined after all to one day be somebody’s old man.

Don’t believe me?

Ask Lenny.