[drop-cap]

I’ve lived in the Los Angeles megalopolis my entire life. As a disabled, wheelchair-riding Chicano, I’ve been confined to certain areas of this polluted, sun-soaked expanse determined by the county’s history of urban development and lack of public transit. This meant pushing my chair was the only reliable transportation I could find until, as fortune would have it, I eventually became one of the lucky few disabled guys who drives using private transportation in Los Angeles. I don’t know how many hours I’ve lost to the 405, stuck inside my accessible car. For years, my hired caregivers and I commuted along the 405 from Long Beach to Westwood, regularly exiting on Wilshire (or Sunset) where I spent the better half of my days at UCLA. As I sat in the passenger seat, I would gaze out the window and see the California sun beaming down upon the urban manifestation of social mobility.

After a few miles along the 405 North, the backdrop ghettos and barrios of the Harbor are interrupted by the beachfront suburbs of South Bay, whose only purpose seems to be to protect West LA from Black and brown bodies with a wall of upper-middle class comfort. During the commute, any watchful passenger can’t miss the sight of the economically disposable and unhoused who have managed to infiltrate the gentrified garrisons of Los Angeles County. The presence of the unhoused, many of whom have some form of disability (physical, mental, or a combination thereof), have caused headaches for homeowners concerned with property values. And the only cure for their headaches is the bludgeon of law and order.

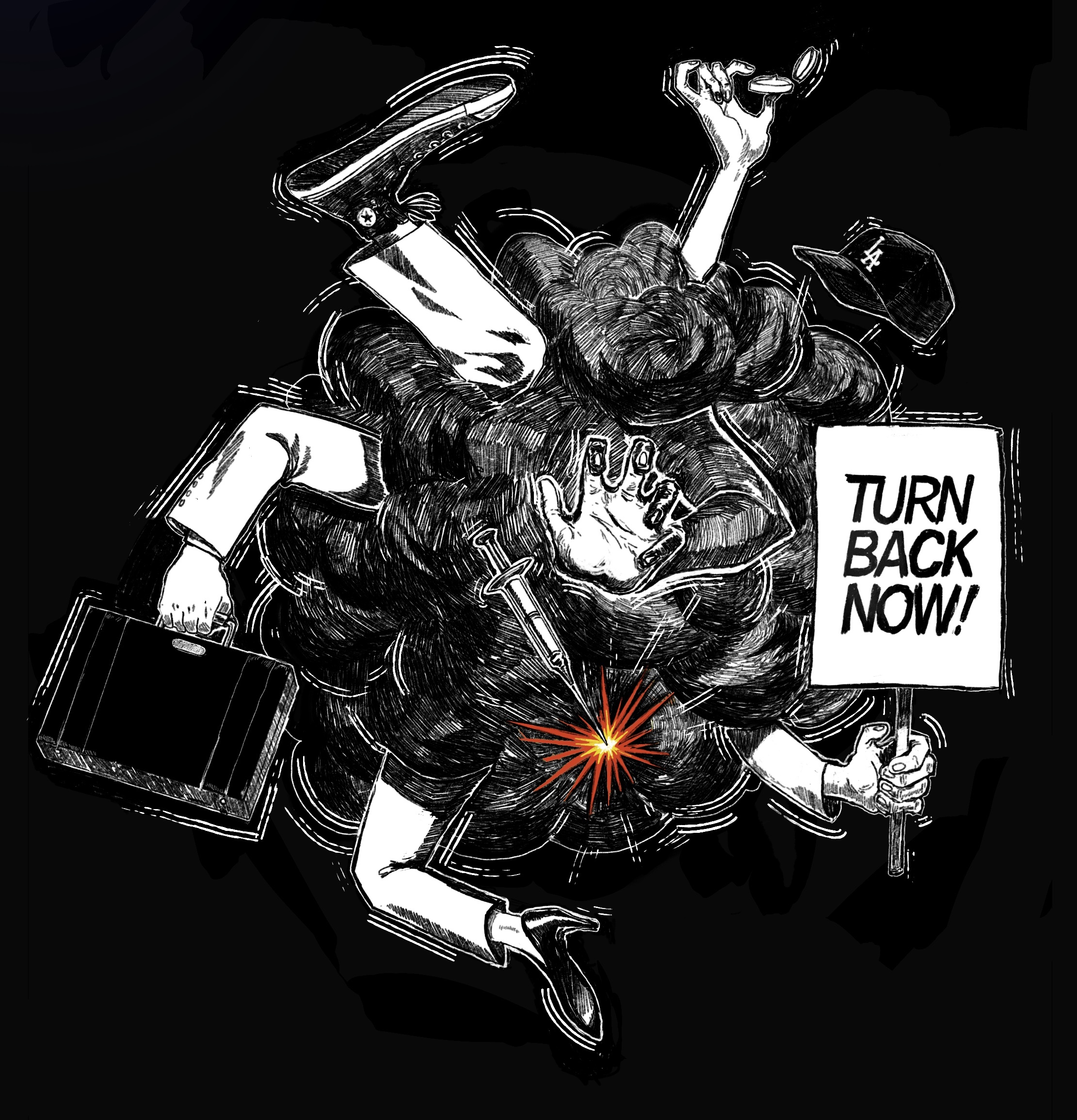

For conservatives, California is a progressive straw man. To those who regularly consume The Joe Rogan Experience or get their opinions from the Shapiro-sphere, California (specifically Los Angeles) is an untenable wasteland à la Blade Runner. Cast as a communist dystopia perdurably burdened by bloated social programs, it is populated en masse by the recycled image of Reagan’s so-called “welfare queens,” who happily dive into Scrooge McDuck piles of government handouts while drug addicts and rapists stalk every corner. My atrophied and contracted fingers have dedicated countless hours chicken-pecking out arguments in online forums, reassuring internet right-wingers that California’s Democrats don’t care about the homeless or disabled any more than they do. The faceless anonymity of the internet doesn’t allow me to see the conservative commentators as they’re introduced to the neoliberal marriage of Republicans and Democrats. But as any devoted internet explorer knows, online political discourse typically devolves into insubstantial retorts that imply anyone with a care for the marginalized is a modern day commissar who obtains sexual gratification by watching their partner carnally ravaged before their own eyes. (Luckily, the good folks at Dispatches have allowed me to present my experiences with little risk of being called a “commie cuck,” and any such accusations should be sent to the official Dispatches email address.)

Under Reagan, California’s newly-unhoused became a symbol of the budget-balancing capitalist state. The casualties of austerity still huddle along freeway underpasses—the only shadowy respite from the California sun

Bipartisan efforts to replace the enormous asylums that historically warehoused the mentally ill, like Patton State Hospital in Los Angeles County, with community-based treatment programs began, optimistically enough, during the Kennedy administration. But without sufficient funding to provide care for those who most needed help, the asylums were closed, their inhabitants evicted from the dark corners of state-run facilities and cast out into the streets. Under Reagan, California’s newly-unhoused became a symbol of the budget-balancing capitalist state. The casualties of austerity still huddle along freeway underpasses—the only shadowy respite from the California sun that simultaneously fries oil puddles on the ground and evaporates beads of sweat off uncovered torsos. Los Angeles’s Skid Row, where many of these people seek shelter, now abuts luxury apartments and yuppie wine bars. Overzealous property developers firmly believe “if you build it, the yuppies will come.” They’re not wrong, Los Angeles has always been ready to accept investments from developers, both foreign and domestic. The boutique homogenization has spread all the way from Skid Row to Boyle Heights to Compton and farther south to my current home in Long Beach.

I often push along Long Beach’s downtown promenades, having Hitchcockian encounters with Bird scooters on the ground that serve as green roadblocks for my wheelchair, while black and white ghetto birds hum in the sky and hunt for transgressors. The urban landscapes of my youth have become unrecognizable to me after a single decade of hyperdevelopment. Hauling my paralyzed body around a space I no longer find familiar serves as a reminder that in an age of speculative real estate sustained by destruction and removal, absence is the only thing that’s real.

Corner discount markets have been repainted and refurbished and artisanal boutiques drone with the hustle and bustle of middle class consumption, as the occasional unhoused person briefly manifests themselves from the shade to ask for spare change. Should this tenuous arrangement (predicated on the unwritten and unspoken promise that the economically nonviable remain out of sight) be broken, a nearby squad car will blare its siren and inform all within earshot that capitalist hierarchies must be, and will be enforced by any means necessary. In the case that a flashing of lights and brandishing of batons fails to restore the street to its predetermined order, these infractions are met with physical force. All I can do is watch, a physical and political invalid, incapable of doing anything for himself, let alone rectifying a schematic brokenness extending beyond my spine.

This is where I think we’ve reached full equality: cops will not hesitate to readjust my vertebrae with a few swings of their chiropractic batons.

As most “urban renewal” enthusiasts know, you can’t start developing dog yoga studios and $17 juice places without the violent removal of those society has deemed too burdensome and unsightly. Who better to enforce the new red lines than the boys in blue? As the LAPD reported in January 2020, one-third of all encounters where an officer used force saw the unhoused on the receiving end. While pushing along the street, I do my best to avoid the all-in-one problem-solving cop, dispatched with surplus military hardware to rein in the parasitic guttersnipe. Most would like to believe that a cop would show restraint when confronted with a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed young quad such as myself, but there are plenty of videos online proving otherwise. This is where I think we’ve reached full equality: cops will not hesitate to readjust my vertebrae with a few swings of their chiropractic batons.

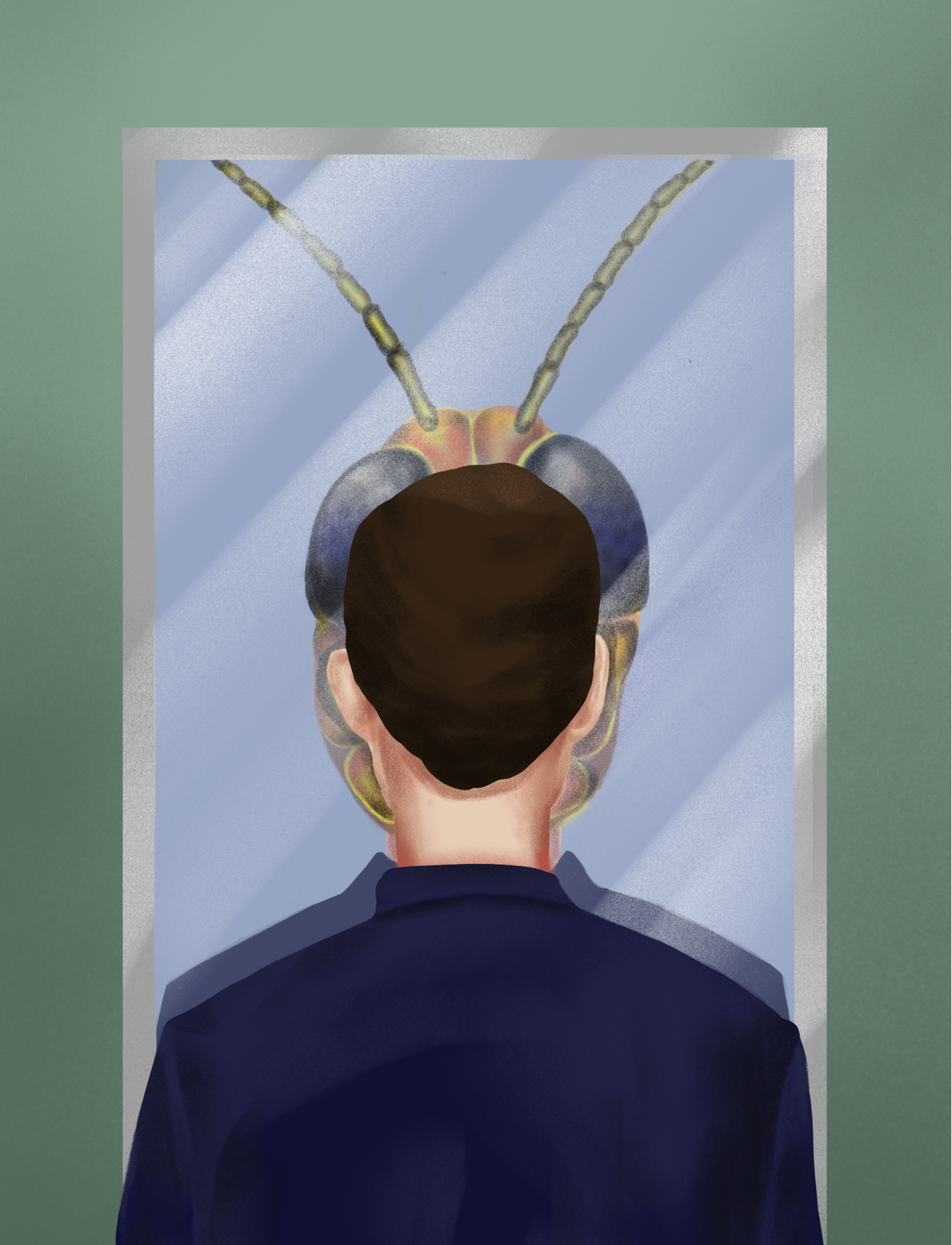

Being a young Chicano in a wheelchair in an urban area is a loaded identity rife with assumptions about my disability and its accompanying history. Having suffered a spinal cord injury resulting in paralysis in the midst of my teenage years, my body had time to develop proportionally before affected sections withered from inactivity and neglect. The unaffected moiety is overworked and tightened through physical compensation so that my physique resembles a wounded warrior's. To the able-bodied spectator in a post-9/11 realm, this can only mean I’ve sacrificed my future hopes of normalcy and fulfillment for the perennial American war machine.

Thank you for your service, young man. What branch of the military were you in?

Unintentional stolen valor because I decided to leave the house to grab a Big Gulp from 7-11. Then again, why would a disabled person bother showing himself in public? Hide your marks and disfigurements, unless they were bestowed upon your flesh and corpus by an insurgent’s round. Let the honor of your allegiance to American adventurism absolve you of the shame of your infirmity. Eyes are upon you. You can participate with us. Let us pity you. Do the only dance you still can do.

You’re so brave. You’re an inspiration. I like how you live your life, unlike all those homeless people who beg on the street.

I am a weaponized token ready to be deployed by mortgage-paying individuals in any hypothetical about economic reform. I am a biopolitical example of how the urban garrisons are used to protect the uber rich from the destitute. Because the people with mortgages and enough capital to displace their social inferiors have inculcated themselves with the illusion that they are a protected class, invulnerable to being crippled by forces beyond their control like mass shootings, intensifying wildfires, or superviruses.

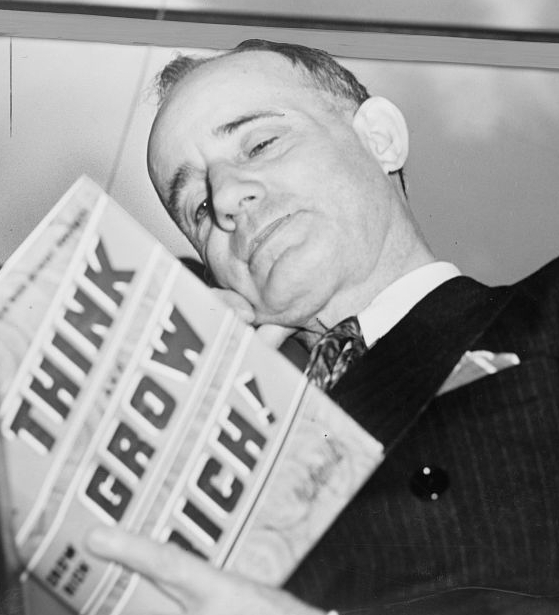

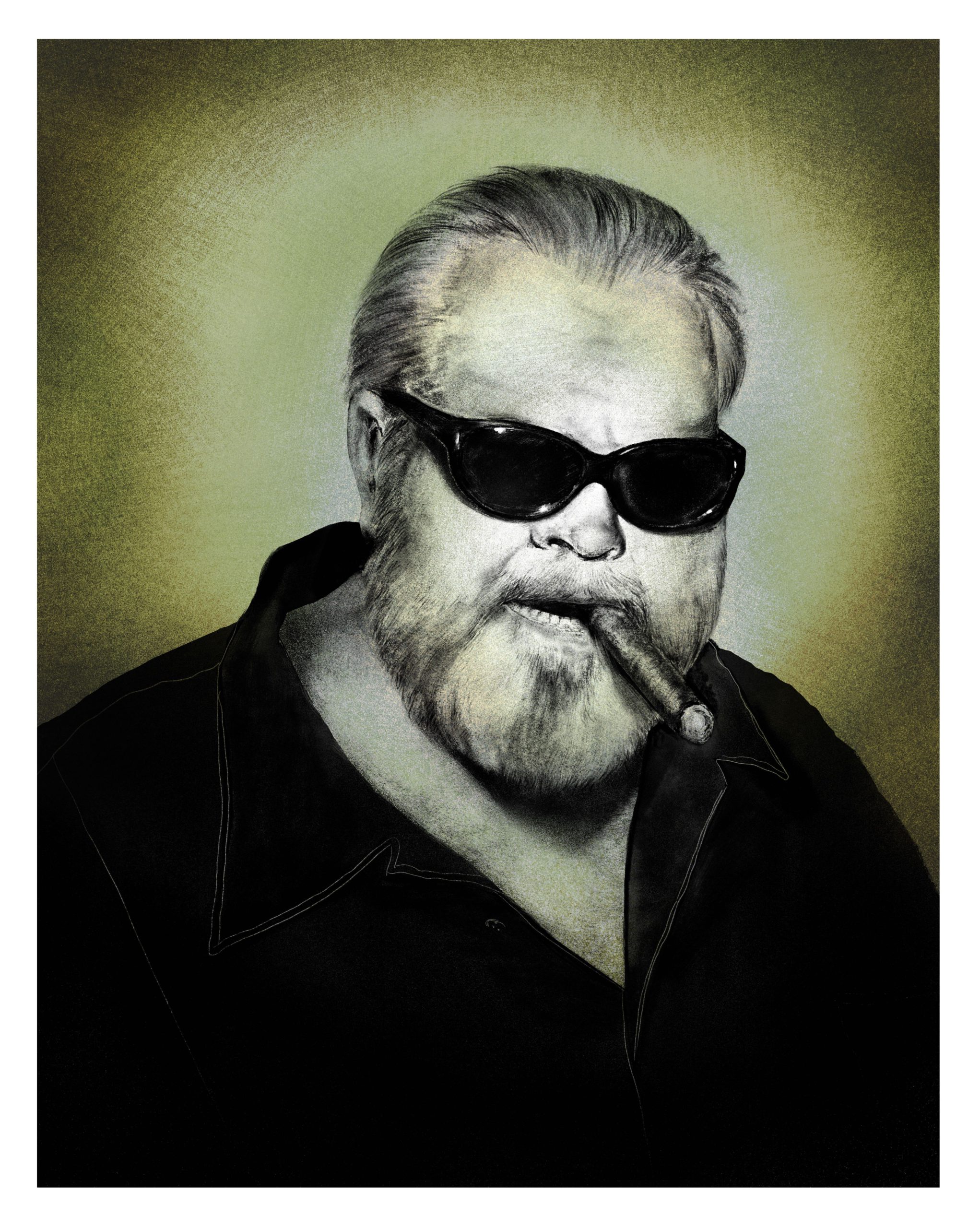

Comfortable Americans suffer from a collective amnesia regarding recessions and other forms of shock capitalism within their lifetimes. In particular, adherents of the musical entrepreneur and convict Frank “Suge” Knight and Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman and the doctrine of disaster capitalism (euphemistically hailed as the “free market”) will argue that the health of a country can be determined by the health of the stock market and the most recent appraisal of their homes. They bother not with the mechanisms that sustain the system. All they know is that most are destined to fail. They say that there is no sickness or infirmity in heaven, so it is their duty as the economic elect to remove the grotesque from their downtown centers and create their own paradise.

Ultimately, I find solace in the depressing reminder that punishing the weak and disenfranchised for inconveniencing the rich with their very existence is the story of America. There is nothing new under the California sun. Yet something about this epoch feels different. Maybe it’s the bias of my fixed relativity, but this moment in time contains an intangible sense of eschatological doom. As if the American project is finally submerged under its own excess. The plague of Covid-19 has shown the world that Americans believe the only way to deal with the paralytics, lepers, and dying is to offer empty words of pity and an unwavering commitment to inaction. The initial murmurs that America could never return to a pre-Covid equilibrium have given way to calls for reform. However, almost a year into the much cited “new normal,” technocrats have only managed to extend their profit extraction into our homes as countless Americans synchronously work the sociologist Arlie Hochschild’s double shift. Meanwhile, those same elected officials continue to disregard the mounting human toll and reopen their states with the hope that beleaguered Americans miraculously avoid Covid while still contracting the virus of capitalism. Thoughts and prayers.

The other day, I was pushing myself around the vacated promenade. A man seeking shelter under a boutique storefront awning sat with a sign, ready to receive alms. Using my feeble hands, I grab some cash and hand it to him. He says, “God bless you.”