March 29th, 2021—Four weeks after my first dose of what Hamilton-loving centrists call a “Fauci Ouchie,” I’m en route to receive my second Moderna injection. Wanting to avoid the dysfunction of Los Angeles County’s Covid-19 vaccine distribution process, I opted to get my shot in Long Beach. Initially, people with disabilities under 65 and other high-risk groups weren’t listed in the first or second vaccination tiers—a gentle reminder that vulnerable populations be damned unless they can provide proof of economic contribution. A typical paradox, considering the disproportionate disability unemployment rate due to the glaring lack of accommodation and de facto discrimination.

Given my history of unconventional employment, I didn’t qualify for a vaccine, even though there was a strong likelihood I could suffer hospitalization or potentially more lethal consequences, should I get down with the sickness. “OOH-WAH-AH-AH-AH” would be my death knell as my lungs fill with fluid. Naturally, this impasse led me to dig through my records and attempt to salvage any pay stub remotely signifying acceptable productivity. Every once in a while, fate lets you be on the winning side of irony and I found an old contract from a local university that officially designated me an education worker for my guest lectures on disability and discrimination. Others like me weren’t so lucky, and instead had to continue with self-imposed house arrest until the powers that be allowed them to join the respectably documented in the queue.

California’s first round of Covid-19 vaccines were administered in December 2020. Understandably, these doses were given to frontline healthcare workers, with the elderly following right after. Susceptible populations would have to wait another three months before their tier got the green light—a delay that was heavily criticized by disability advocacy groups as the data clearly demonstrated that individuals with co-morbidities and preexisting conditions had higher mortality rates. But now that vaccines are open to most of the population, another one of my communities is experiencing low rates of vaccination, but for very different reasons.

At the time of writing, Hispanic Californians are the least vaccinated demographic in the state. While 49% of non-Hispanic white Californians have received the vaccine, only 27% of those who self-identify as Hispanic have received theirs. I don’t have a complete understanding of why Hispanics are reluctant to get the vaccine, but my suspicions lead me to believe that at least part of the issue lies in the historic abuse of Hispanic populations by institutionalized medicine.

“Mijo, don’t get the vaccine,” my father warned me in Spanish after I told him I had scheduled my first appointment. “It’s filled with the same pesticides they used to spray on Mexicans.”

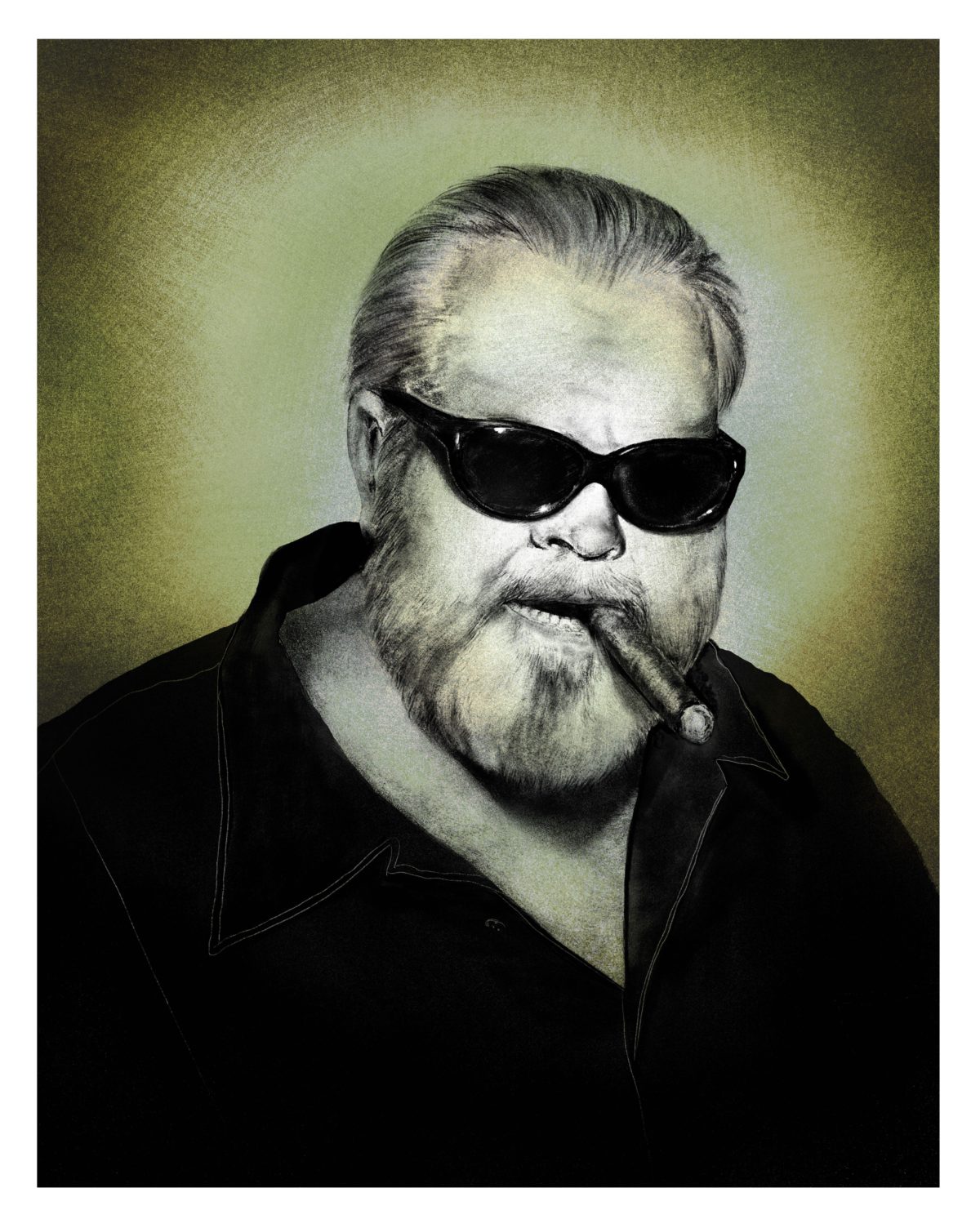

Being a salt-of-the-Earth Mexican whose main remedies consist of VapoRubyEsprait, my father was misinformed about the contents of the vaccines and sounded like José Rogan. However, he was correct about one thing: In 1917, there was an influx of Mexican migrants fleeing the Mexican Revolution. The El Paso mayor at the time, Thomas Calloway Lea Jr., deemed them to be “dirty lousy destitute Mexicans” and feared that they would bring diseases with them across the border. After using all his ACME brand contraptions and failing to control the armies of Speedy Gonzales, Lea threw his 10-gallon hat into the dusty tierra and comically stomped on it repeatedly in frustration.

“Oooh, I’m gonna get those lousy Mexicans!” Lea said, probably.

Lea needed to think of another way to curtail the potential spread of unwanted contagions, both micro and macro. So in the name of public health, he ordered the pesticidal cleaning of all migrants and workers entering the United States from Mexico. As they crossed the border, immigrants were forced to strip off their clothing as their bodies were doused with flammable chemicals. Their clothes were fumigated with hydrocyanic acid, sold under the trade name “Zyklon B,” which would go on to be the gas of choice in Nazi death camps to murder millions that were also labeled “unclean.”

Like many other multi-million dollar sports arenas, the construction of Dodger Stadium in Chavez Ravine is replete with more peccancies and asterisks than the home-run records of the early 2000s.

Often conspiratorial thinking among working class Hispanics is derided by elites as a distrust of the clinic caused by lack of education. While distrust of institutions is at the heart of any conspiracy, Hispanic suspicions toward white doctors in white lab coats is well founded. Generations of “disinfected” Mexicans and Chicanos in the United States have experienced numerous injustices committed in the name of “public good.” From the border gassings to the law and order rhetoric of Operation Wetback and subsequent deportation programs to eminent domain displacement, Hispanic people, have suffered in the name of progress.

Edifices constructed to serve the “public at large” (i.e. no abnormals or malcontents) on stolen land add insult to injury by excluding those who were harmed to make way for the future. Dodger Stadium in particular is a monumental example. Dodger Stadium’s significance within Los Angeles’s urban canvas can be interpreted several ways: For Chicano sports fans, it’s a cathedral sanctified by 56,000 blue-clad parishioners worshiping at the altar of St. Vincent Scully and St. Thomas Lasorda. But for those born before 1960, Dodger Stadium is a cold, concrete reminder of the deracination of la raza.

Like many other multi-million dollar sports arenas, the construction of Dodger Stadium in Chavez Ravine is replete with more peccancies and asterisks than the home-run records of the early 2000s. Home in the 1940s to three flourishing Mexican neighborhoods, Chavez Ravine was declared “blighted” in 1949, and a decade-long battle commenced in 1951 when the city proposed to use the land for public housing designed by well-known architects Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander. Eventually the city seized the land through a combination of eminent domain and underhanded real estate deals. Those who resisted were removed by force. As support for public housing waned during the anti-communist crusades of the 1950s, led by the Los Angeles Times, the land was offered to the Brooklyn Dodgers as incentive to relocate, which inevitably they did.

On January 20th, 2021, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti claimed the vaccine hub at Dodger Stadium was the largest in the world after it delivered over 7,700 doses in a single day. Institutional malfeasance has come full circle within the span of a century as the circumstances of the stadium’s construction have come back to haunt the city. Chicano residents—potentially the great-grandparents of the city’s current population—survived gassings intended to make them clean enough to become Americans and were subsequently dispossessed of their homes in the Ravine. And now, the Chicanos of Los Angeles are asked to trust medical institutions at a facility built on the destruction of their own communities.

I’m obviously sympathetic to the intergenerational trauma suffered by my father and others alike. The fears of being experimented on or exploited by the government are historically grounded. It seems like no matter whether you buy into medicine or try to distance yourself from it, death and negligence are unavoidable parts of existing as a hyphenated-American. Proportionally, Hispanic/Latino Covid-19 mortality rates in Los Angeles are almost triple that of White Angelenos. Per 100,000 White residents, 121 have died. Whereas per 100,000 Hispanic/Latino residents, 357 have died. Perhaps the most daunting aspect of all this is trying to convince my paranoid immigrant father that it isn’t the vaccine that puts his life at risk, or even the misinformation he’s received about it, but rather the historical trauma bestowed upon him that made him so susceptible to believing it.

I’m old enough to remember the halcyon days of down-to-earth conspiracy theories like the ones promulgated by Sarah Palin and the Tea Party, long before QAnon showed sleepy, middle class Americans how baroque conspiracy theories could be. While protesting in our nation’s capital, the Tea Party and its ilk megaphoned that the Affordable Care Act would lead to panels overseeing who would live or die, as doctors with globalist grins decide whether or not your grandma is worth saving. “Keep your FEMA-death-camp-funding government paws off my insurance policy! You want us all dead!”

Americans are much more comfortable supporting policies that lead to mass death than contending with their own individual mortality. It’s necropolitics 101: any accommodations needed to ensure the health of the public are viewed as necrotizing agents, hell-bent on eroding the rights of individuals or, as they’re more aptly known, the operations of big business. The free market they champion is the true death panel.

I pulled up to one of the kiosks at the Long Beach Convention Center (now sheltering hundreds of migrant children, some of whom have contracted Covid-19 while there) and I presented my bare arm to a PPE-clad nurse and received my publicly funded prick. As I waited inside my car for 15 minutes to make sure the microchip inside the vaccine booted up properly, I wondered if people in my communities would follow suit or if it would indeed be “White Boy Summer.”