Editor’s Note: The following is Dispatches’ day-by-day account of the scene in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention.

Contents:

Sky O’Brien: MONDAY

Marius Sosnowski: MONDAY

Sky O’Brien: TUESDAY

Marius Sosnowski: TUESDAY

Sky O’Brien: WEDNESDAY

Marius Sosnowski: WEDNESDAY

Sky O’Brien: THURSDAY

Marius Sosnowski: THURSDAY

Sky O’Brien: Monday, August 19th, 2024

It’s grain filling season in Illinois. All around me, the corn fields are having sex, and lots of it. Those are the words that Brian, the Free Methodist sitting next to me on the train to Chicago, uses to describe the fertilization of corn husks. “The tassel (the male part of the corn) pollinates the ovules on the ear (the female).” I look outside my window and see the never-ending fields of corn on either side of the train. “You’re telling me these fields are making love,” I ask, because I don’t know much about agriculture, and I’m trying to find my feet in the conversation. “That’s right,” Brian says. “This is the stronghold of American corn.”

It’s the kind of conversation you can only have on a train. We’ve been talking since he got on at Lincoln and I asked him about corn, which seemed like an appropriate thing to ask a guy with a Nutrien sticker on his laptop in the middle of Illinois. “I’ve got corn and soybeans in my blood,” he said. He’s not lying. His ancestors, he tells me, farmed corn in the east of the state for 200 years. His grandfather did some early work in GMO corn seeds: “Bigger bushels means more kernels, which means a higher yield.” His father had the farm until he was sent to Korea. On the subject of pesticides, which is Brian’s line of work, he tells me about Roundup, which I’ve seen pilots spray from planes over these fields to keep the insects off. “If an insect bites into a stalk that’s been sprayed,” Brian says, not quite cheerfully, “its stomach will explode.” “Like a bomb,” I say, and Brian nods. “Those aerial sprayers earn their keep.” It’s a dangerous job. “I came back here for my father’s funeral,” he says, “and in the cemetery, three graves along, there was a guy—thirty-two years old—who was spraying crops. He flew into the powerlines.”

I tell him I write for this magazine and I’m on my way to Chicago to see what’s going on at the DNC, if it’ll be anything like 1968, when the police had iron fists and the Yippies, fed up with war drafts and a Democratic Party keen on staying in Vietnam, nominated Lyndon Pigasus Pig—a real pig—for president. “Be careful,” he says, and proceeds to tell me that he’s not afraid to talk about politics, even when I invite him not to: “I’m going to vote for the best person for the job. But I do have one non-negotiable,” he says, and his eyes get that Free Methodist glaze. “I don’t believe in taking the life of an unborn child.” Naturally, our conversation dries up, but not before he tells me about Jesus, who died for his sins, and Boise, Idaho, where he lives now: “It’s the kind of state where you can play golf in the morning and ski in the afternoon. We’ve got it all, you see.”

For the last part of the journey, we turn to our laptops, and when I’m not writing, I peek at his screen and see numerical tables of corn markets, corn prices, and corn futures. When the train’s automated voice says, “Next stop, Chicago,” I’m on Instagram looking at an AI-generated video montage of Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. In the first scene Trump and Harris are holding hands and walking on a beach. In the second scene they’re kissing on a stage in front of an audience. In the third, Harris is pregnant, and Trump is rubbing her baby bump.

I’ll be in Chicago in about forty minutes. My first stop: a cobbler outside Union Station, who I’ve paid $7.00 to store my backpack for four hours. Then, the protests in Union Park, where, according to the organizers’ press release, “tens of thousands” are expected to “amass” for the “March on the DNC for Palestine.”

12:27pm

People are amassing in front of the porta potties. There are seven porta potties for what looks like a crowd of 10,000 protestors. The line for the loo is so long, so perfectly straight and single file, it cuts through Union Park, parting the people like a bowsprit. If everyone keeps drinking the free bottled water being handed out by people in yellow vests, the back of the line could reach the stage on the other side of the park, where speakers are asking Killer Kamala if she’s thought about not sending weapons to Israel. “Right now,” says the speaker on stage, “hundreds of war criminals are in Chicago to celebrate themselves.” She goes on: “Today, at the DNC, the keynote speaker is Genocide Joe.” A few minutes ago, I picked up our press passes. One for Sosnowski, who’s on his way, and one for me. Having it means we can stand a bit closer to the stage, if we want to.

12:29pm

Stacks of placards lie here and there on the grass, ready for people to pick up at will when the march begins. They remind me of gardening tools. One of the placard designs has a picture of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris with their best red laser eyes. The text: “Democrats fund the Genocide of Palestinians.”

12:35pm

There appear to be more porta potties in the park than there are flags of Israel. There, on the outer perimeter along Washington Boulevard, I see a small Israeli counter-protest taking place. They are ensconced in such a strange part of the park, away from everything and shielded by the police, that it seems as though they fell out of the sky and landed there by mistake. They’re flying six stars of David. Around them, Pro-Palestine supporters are asking if they haven’t got anything better to do on a Monday afternoon. Police everywhere, including Superintendent Snelling.

12:45pm

More police, including Superintendent Snelling.

1:00pm

Back near the stage, I see protestors walking around with a giant puppet of Benjamin Netanyahu. He does not look good. Both of his arms are very long, like the hose on a vacuum cleaner, and he has blood on his hands. His neck appears to be a broomstick. “Fuck you, Netanyahu,” says a guy with a motorbike helmet on his head when the puppet passes him by. “We want Palestine to win.”

1:40pm

I am sitting on a bench by the basketball courts, far away from the stage where the latest speaker is talking, loudly, about their refusal to be silent. Just then, a red GMC Chevy parks along Randolph St. next to the park. It has two flags of Palestine hoisted on the trunk. On the rear window, it says, in all caps, “REDNECKS SUPPORT PALESTINE.”

2:00pm

I overhear someone say, “I’m not into the cops.”

2:05pm

Thousands of police officers are sitting on their bicycles along the perimeter of the park. They remind me of dads standing at the back of a Taylor Swift concert, watching their kids.

2:10pm

I’m talking to a cop with a short, red-haired woman named Patty. Patty saw me taking a video of the Christians standing outside the First Baptist Congregational Church on the corner of Ashland and Washington, on the east end of the park. I was trying to document people’s interactions with their banners, one of which reads, “Christians: Jesus will vomit you out of his mouth” (it’s from the Bible, Revelation 3:16). Not from the Bible is what one Christian is yelling at a pro-Palestine protestor across the street: “God’s got his finger on you, you little perv!” Patty asked me if I’d be a witness while she asked the police if the Christians had a permit to say those kinds of things. There are better ideas in the world, but at least she had plenty of police to talk to.

2:17pm

My time as Patty’s witness is over. The message from the police: “If you don’t like what the Christians are saying, you don’t have to listen to it.” Suddenly, Cornel West appears beside me, and I am surrounded by cameramen.

2:21pm

If you want to buy a flag of Palestine, a small one will set you back $10. A big one is $20.

2:30pm

“No fascist Trump! No Cold-Blooded Kamala! No Genocide Joe!”

2:54pm

Sosnowski is here. We are standing where the Jesus congregation was calling everyone a pervert. This is where the march begins. As the protestors take their place in the street, superintendent Snelling holds a rapid-fire press conference in the middle of the intersection. I’m so close to him I can see the four silver stars on his shirt collar. A reporter asks, “What’s your biggest fear for today?” Snelling says, “I have no fears.” A few minutes later, the march begins, and Sosnowski and I disappear.

Marius Sosnowski: Monday, August 19th, 2024

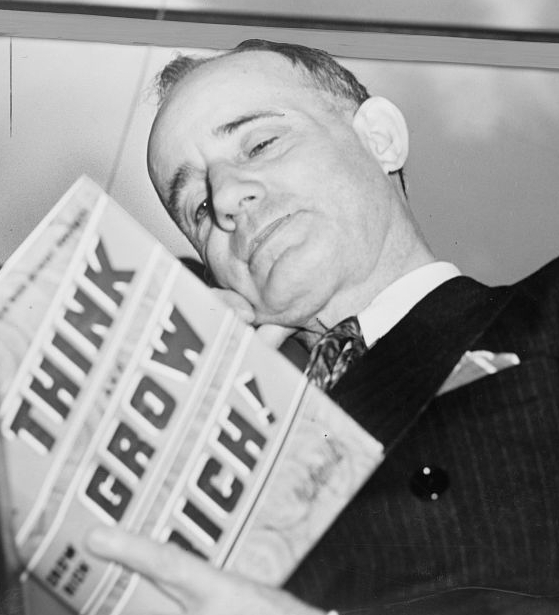

“With Nixon as the only alternative, Kennedy was beautiful—whatever he was. It didn’t matter. The most important thing about Kennedy, to me and millions of others was that his name wasn’t Nixon. Far more than Stevenson, he hinted at the chance for a new world—a whole new scale of priorities, from the top down. Looking at Kennedy on the stump, it was possible to conceive of a day when a man younger than 70 might enter the White House as a welcome visitor, on his own terms.” — Hunter S. Thompson, from a January 1970 letter to Jim Silberman

At 38,000 feet, the heady atmosphere produced by thin recycled air and travel nausea makes it easier to view the world below as something more akin to a memory palace, a phantasmagoria, a collection of shifting plates whose surfaces morph like ChromaFlair, where the same dramas play out in perpetuity but with different actors playing the key roles.

The night prior, despite my pending red eye to Chicago, I found I needed a “last meal” at a tavern in the dark woods of Montrose, a little community near Pasadena’s mysterious Jet Propulsion Laboratory some fifteen miles north of my apartment. It seemed fitting in an odd sort of way, for I didn’t know whether or not I would be returning from Chicago with permanent scars—psychic or otherwise. The meal took on a compulsive form of importance, like symbolism, like a handshake from someone dear before crossing a threshold. I knew I’d be too hopped up to sleep anyhow. Faced with the prospect, however slim, of stepping into history itself carried enough electric energy to send me back to those raw frequencies of childhood, when the knowledge of any and every divergence from the routine carried a strong hint of the miraculous.

Now, aboard American Airlines flight 1021—LAX to Chicago O’Hare—I wonder if anyone else has similar thoughts bouncing around their sleep-deprived head. None of the passengers appear any different or more aware. Today is simply another Monday morning, six a.m. flight to anyplace, U.S.A. Maybe the one man with three hats on his head (two straw cowboy hats with a baseball cap on top) or the one guy partial to the spirit of the Yippies (in Birkenstocks, with long curly hair, scruffy beard, and a very late ‘60s bandana wrapped around his forehead). Is it ego or something else that carries this impulse of mine—likely borne from a sense of pure fear—to self-mythologize in the face of the unknown, to step upon the shifting plates of the present acutely aware they are shifting?

I re-read the press release for the March on the DNC for Palestine that will mark the first protest of the convention. I’d been struggling to come to terms with an approach. I find myself ever trapped in a bitter struggle between the temptations of cynicism and the tenderness of hope. Granting access to practically all recorded history, the Internet has had the unintended effect of allowing the past to take on ever larger proportions, proportions which bury the present in a redundancy of images. When I saw the Kamala Harris poster that read “Forward,” designed like Shepard Fairey’s iconic Obama, it struck me as a facsimile of a facsimile. Buried under these daily sensations, the near past takes on the mythic proportions of ancient history, except it wears the veneer of something fabricated, something like cheap knockoffs in the manner of the “smart” wear H&M hocks to last only the length of the gig. All the media’s comparisons to 1968, to 1996, to anything and everything, predicated the bizarre feeling that whatever was going to happen today, this week—especially the protests—just wouldn’t live up to the hype. In this moment, I want to believe history is the imprint of footsteps on wet concrete instead of wet sand, but would I recognize the difference given the chance?

The captain announces we are 40 minutes from landing. The anticipation of witnessing a Great American City rise up out of the vast midwestern flats begins to build. I put my reading away and focus on the picture outside my window. The Boeing 737 careens through gargantuan clouds with a shudder as it adjusts course and descends. Bit by bit grids and serpentine networks of suburban housing developments break apart the loamy fields. Baseball diamonds, playgrounds, ponds, and swamps. The green gaps shorten as the human footprint expands—industrial parks and expansive facilities, the interstate widens lane by lane with ever more elaborate interchanges. We soar over an Amtrak train chugging along, eastward, eastward, until out of the hazy mists on the distant horizon, the city appears like a charcoal mirage.

Initial impressions of Chicago: the Blue line rattles and whistles its way along the median of Interstate 90 toward the city. A billboard reads “The Future Is Built in Chicago.” I transfer to the Brown line “L” elevated train in the Loop and catch the architectural spectacle on full display. We cross the Chicago River, where the sequence of iron bascule (or “seesaw”) bridges stretch away either side of ours like ruddy hurdles. Towers of steel and concrete in neo-Gothic, Art Deco, Modernist, and International styles loom over everything. I admire the voyeuristic, Edward Hopper-esque view the elevated trains offer, like an amusement park ride through some cardboard city. Elevateds, like commuter trains, offer you a look at the back ends of things—fire escapes, back doors, junk-strewn yards, pipe networks, and people (when you can catch a glimpse) with their guards down.

The towers get shorter as we travel into the North Side. In Miami and the Siege of Chicago, Norman Mailer compared Chicago to Brooklyn in a way I now see makes great sense—Chicago as the Brooklyn of fulfilled potential had it not been sacrificed to its inexorably luminous sibling across the East River:

…neighborhoods which dripped with the sauce of local legend, and real city architecture, brownstones with different windows on every floor, vistas for miles of red-brick and two-family wood-frame houses with balconies and porches, runty stunted trees rich as farmland in their promise of tenderness the first city evenings of spring, streets where kids played stick-ball and roller-hockey, lots of smoke and iron twilight. The clangor of the late nineteenth century…

But Chicago also evades comparison. It’s been over 50 years since Siege of Chicago, and yet so much seems unchanged, even the proliferation of new steel, glass, and updated construction techniques appear integrated in a harmonious way, following the lead set in the late nineteenth century when Chicago’s vengeful quest for beauty reigned. I disembark at Fullerton Station and stroll through the collegiate, richly arboreous streets of Lincoln Park to drop my bags off and reset. It is warm, but not unpleasant. I feel closer to the South than the West, as the humidity lines my brow with beads of sweat and the cicadas roar in the tall trees.

My co-correspondent is already in the thick of it. Having arrived a while earlier, O’Brien went straight to Union Park where the “March on the DNC for Palestine” protestors were gathering. In the absence of any press credentials whatsoever, O’Brien scores us press passes to the protest. I arrive at Ashland station, walk across the canopied wooden decks flanked by cast iron supports and ornamental rosettes, and descend the resonant stairs behind scores of people in a scene that feels lifted out of the 1930s. Flags, drums, shouts, chants, a sea of people spread across the sun-saturated greenery; reds, greens, whites, and blacks are the palette, keffiyehs and N95 masks the adornments.

O’Brien finds me relatively quickly and hands me my lanyard with a laminated card that reads “Press.” We move toward the stage where the speeches continue as they have all morning. I just miss Cornel West. I nod to a person in a NASCAR baseball cap carrying an “Immigrant Rights For All!” sign. Gathered stage left, a group of Jewish people in Orthodox garb dance signs that read “State of Israel Does Not Represent World Jewry.” Across from the First Baptist Congregational church at the corner of Washington and Ashland, Christian trolls have gathered to decry the licentiousness and hell-bound fervor of the protestors. One in a “Turn or Burn” t-shirt holds up a sign that reads “Jesus Will Vomit You Out of His Mouth.” A spectacularly Christian image pending iconization, I’m sure of it.

Union Park, the first park to be racially integrated in the city, is in Chicago’s near West Side, a once low-income neighborhood undergoing rapid gentrification, as evidenced by the tall fresh apartment blocks that scream “rooftop natural wine party under the string lights.” We start a conversation with an elderly man named Melvin who tells us we’re basically “in the hood, but you wouldn’t know it today.” I tell him I thought that was the South side. He says there’s a hood on every side. He grew up just up the street, at the Henry Horner Homes, a project on the east side of United Center, and coached a lot of basketball players who graduated to the NBA. “Jordan. He wasn’t shit. All free throws. Look at the stats. He had a referee who looked out for him in like 80% of his playoff games.” Melvin’s guarding the generator today for his friend’s electrical company, but he says he’s retired. “Diesel. If someone messed with this thing it’d blow sky high.” He points a few more things out in different directions. “The whole neighborhood is changing,” he muses.

Pressure mounts as protesters begin to line up on the park side of Washington Boulevard. The police are everywhere, on bicycles, on foot, lining perimeters nearby and in the distance. They have fixed, immovable faces. Adults of all ethnicities, all ages. Another class of cops stand in the center of the intersection; they wear peaked cap officer’s hats and white button-ups. They are larger, bulkier, harder-seeming in every conceivable way—like a breed of man built for intimidation—with faces chiseled from granite, unrelenting, implacable, features stolen from statues and busts. Who are these men? Do the men forge the force or does the force forge the men? The press swarm around them and the one who steps forward, with a chin that could split wood, is Chicago Police Department Superintendent Larry Snelling.

O’Brien puts his voice recorder into the swirl of bodies. One reporter asks, “Do you have any fears for the day?” “We have no fears,” Snelling responds. “We’re just focused on getting the job done.” When the impromptu conference breaks, there’s some signal and the ground cops mount their bicycles one-by-one, kicking off with an unexpected sort of grace and swinging a leg over like they’re cavalry. We follow the onrush of photographers to the sidewalks of Washington and climb onto some scaffolding for a better view of the oncoming marchers. “Palestine will be free! (Palestine will be free!) From the river to the sea! (From the river to the sea!)” the refrain goes. “When one of us is under attack, what do we do? (We fight back!)” The woman leading the chorus has fire in her vocal chords, hypnotizing passion. Deep drums complement her alto calls. She wears a white, gray, and black keffiyeh wrapped around her head and spins in the center of a circle of people, just behind a set of speakers rigged on wheels.

Leading up to the trip, I’d felt a real desire to make some—any—sense of this moment in time, of these almost religious urges, in a way that felt appropriate to the level of perceived emotional investment, in this new century when paradigmatic shifts of epic proportions breed more powerlessness and disaffection into millions of young adults. And yet here, as I clutch a diagonal support beam on a Chicago street, everything feels exhibitionistic, beset by a proliferation of cameras and smartphones and bored police officers, with a whole squadron of people on the wings wearing expressionless faces, climbing on objects to make images, and marchers in the middle of the road, leisurely smiling and lifting their signs while basking in the invisible glow of the ever-present lens.

By 3:31 pm, we’re back on the Pink Line to pick up O’Brien’s luggage from a cobbler across the street from the Willis Tower before he closes up shop. At the station, CTA workers crack jokes. Onward flows the rest of the world unmoved.

9:40 pm. We eat sandwiches and drink beers at Halligan’s pub, a wedge-shaped Irish bar on the corner of Orchard and Lincoln. Onscreen, Tim Walz and his wife sit in their box frowning. They will do a lot of that, in between smiles and hand-over-their-hearts gestures. Golden State Warriors (and USA Olympic team) coach Steve Kerr gives a speech, invoking Steph Curry’s “go to sleep” gesture from the Olympic final to call on everyone to put Number 45 to bed. “Do you think he asked to speak or does someone like that get invited?” O’Brien asks. “Big donors, probably,” I say.

By 10:22 pm, we wonder how many people actually go for all the sentimentality at these conventions. Some of these participants wouldn’t do half-bad on a well-scripted TV drama or romance. Finally, President Biden is summoned by his daughter where he takes in a four-and-a-half minute ovation, lips parted, eyes glossy.

Eventually, we will rejoin the night. When we do, it is crisp, with a steady wind blowing from the lake, everywhere a scent of moisture and wet earth. We march down Webster to Lincoln Park, looking for the ghosts of Yippies asleep in the park. We try guessing the statues. (Neither of us gets Hans Christian Andersen.) We stop at the bridge over South Pond, transfixed by the scene. The sky is fluorescent with the blue supermoon; great clouds drift swiftly across, glowing temporarily, like electric jellyfish, over the tops of the incandescent skyscrapers. “Hotel Lincoln” shines in red neon to the southwest. In front of us, at the center of the bridge, are two people seated on chairs in front of a laptop, their faces lit by a ring light, a cameraman behind it in the darkness; they are silent, frozen. Minutes pass without speaking, without movement, only the ripples of the South Pond below, shimmering. I’ve never seen anything like it. I watch O’Brien run over to the man seated on a bench nearby. He returns. “DNC coverage. Channel 3. Madison, Wisconsin.”

We stop at Ulysses S. Grant’s monument. Pass the Garibaldi monument. “There,” he says, taking off toward a decline in the path toward the underpass beneath La Salle Drive, “that’s where the Yippies got tear gas in their eyes in ‘68.” In the meantime I spy Benjamin Franklin’s iconic silhouette on his pedestal. “Genet said the cops came down this hill here, and this,” O’Brien gestures around us like a madman, “this is where all hell breaks loose. And now, 56 years later, it’s empty! Not a soul around.” “Well it’s just the first day,” I offer. “It was the first day then, too,” he pants. We watch the cars on La Salle hit Clark. “Netflix,” I shrug.

Sky O’Brien: Tuesday, August 20, 2024

When we walk into The Corner Bar in Chicago’s North Side, Sosnowski and I discover something about Kamala Harris: She’s not in Chicago. According to the live broadcast on the only TV above the bar, she’s in Milwaukee. Now, some people will argue that it is the responsibility of political correspondents to know the whereabouts of the Vice President of the United States, especially when she’s up for promotion. But we are not political correspondents, and the fact that we didn’t know Kamala Harris would be rallying in Milwaukee while her employers were rallying in Chicago is more a reflection of our failure to anticipate the ambition of the Democratic Party: they’ll do anything to split a TV screen in half.

As we watch Bernie Sanders on stage in one city alongside Kamala Harris on stage in another, Sosnowski and I realize that we’ll do anything for a meal. The Corner Bar doesn’t serve food, so we tell the bartender we’ll be back and we walk to the tavern at the end of the street. I am sometimes afflicted by the need to ask questions that don’t need to be asked, and when we walk inside the tavern I ask the bartender if they serve food. “This is a restaurant,” he says, and points to the host sitting outside. “She’ll seat you.” But she won’t. The kitchen is closing in 15 minutes, and two big parties have just sat down ahead of us. “You’re looking at an hour wait time,” the host says.

With no TV in the tavern, we’d miss the Obamas, so we go in search of something quicker. There’s a taqueria nearby. I make the mistake of not checking the prices on the menu before walking in, so I end up paying $17.00 for two tacos. They’re delicious— “Chef,” says Sosnowski, imitating a character on The Bear, “the texture of every grain of rice is perfect”—and we return to The Corner Bar with carnitas in our system. The streets are darker now, and on our way we see blue rectangles glowing behind the open windows in the houses on Leavitt Street: Everyone, it seems, is watching the DNC.

“No one’s watching that shit,” a guy at the bar says to his friend when we sit down and look up at the TV. Senator Tammy Duckworth is addressing the crowd, but we don’t know what she’s saying because there’s no volume on the TV and the remote, handed to us by the bartender, offers no clear path to closed captions. By the time Doug Emhoff takes the stage and tells us he drank Slurpees after Little League practice when he was a kid, I’ve brought up another live stream of the convention on my phone and propped it against a straw holder on the bar. If I hadn’t acted so quickly, we’d have missed one of Emhoff’s big revelations: He named his first fantasy football league “Nirvana.”

When Michelle Obama takes the stage and tells us “Something wonderfully magic is in the air, isn’t it,” someone in the bar is playing “American Pie” on the jukebox. Thus, it is to the sound of Don McClean’s eulogy for a lost past that we hear/read Michelle Obama talk about the promises of America’s future:

We’re feeling it here in this arena, but it’s spreading all across this country we love. A familiar feeling that’s been buried far too deep and for far too long. You know what I’m talking about. It’s the contagious power of hope. The anticipation, the energy, the exhilaration of once again being on the cusp of a brighter day. The chance to vanquish the demons of fear, division, and hate that have consumed us and continue pursuing the unfinished promise of this great nation. The dream that our parents and grandparents fought for and died and sacrificed for. America, hope is making a comeback.

At all the right moments in the former first lady’s speech, the camera swivels to the faces in the crowd at the United Center, bringing us a stadium vision of the cheering, vibrating mass, then zooming in on individual faces to see their blazing eyes, eyes ecstatic, eyes agog with wonder and reverence for her message of recycled hope.

And it’s the close ups on people’s eyes, streamed to me on two screens in this small Chicago bar where Sosnowski and I are watching, that lead me to an idea: I don’t know how they’ve done it, but the Democratic Party has found a way to wash their hands of Israel and Gaza for a few hopeful days, days that promise to turn into weeks and months and maybe even years. Somehow, with Harris and Walz in Milwaukee, the Democratic Party has found the words to remind the good citizens of America that their party always has been, and always will be, the Party of Hope. Just look at those faces cheering for the Obamas, faces lifted and lulled by blue light and blue words. We can’t hear the convention on the TV in The Corner Bar, but I know the cheers in the United Center are loud. So loud that, if I listened to them long enough, I, too, could forget the sounds of American bombs falling on Gaza.

When Barack takes the stage, not only is Hope making a comeback, but so too is his 2008 campaign slogan, updated and refreshed for a Hopeless moment. “Yes, she can,” he says of Kamala Harris. “Yes, she can.”

Marius Sosnowski: Tuesday, August 20, 2024

I haven’t stayed in a hostel in over twelve years. The arrangement is, as I recalled, very European. And from what I can tell, it’s populated mostly by foreign travelers. Harmonious and courteous, strangers maneuver in silent sync at breakfast. No one calls the manager. If I can’t think of the last time I witnessed this much civility in a large room, perhaps America isn’t, in fact, “winning” (winning at what?), as President Biden so emphatically put it in his Goodnight, Sweet World, Goodnight speech on night one of the DNC. Of course, the dark vision conjured by the other side of the partisan line is a waste of imaginative faculties. Yet, I’d like to think this kind of unwitting civility is a key component of the “social” in the socialism many Americans are allergic to.

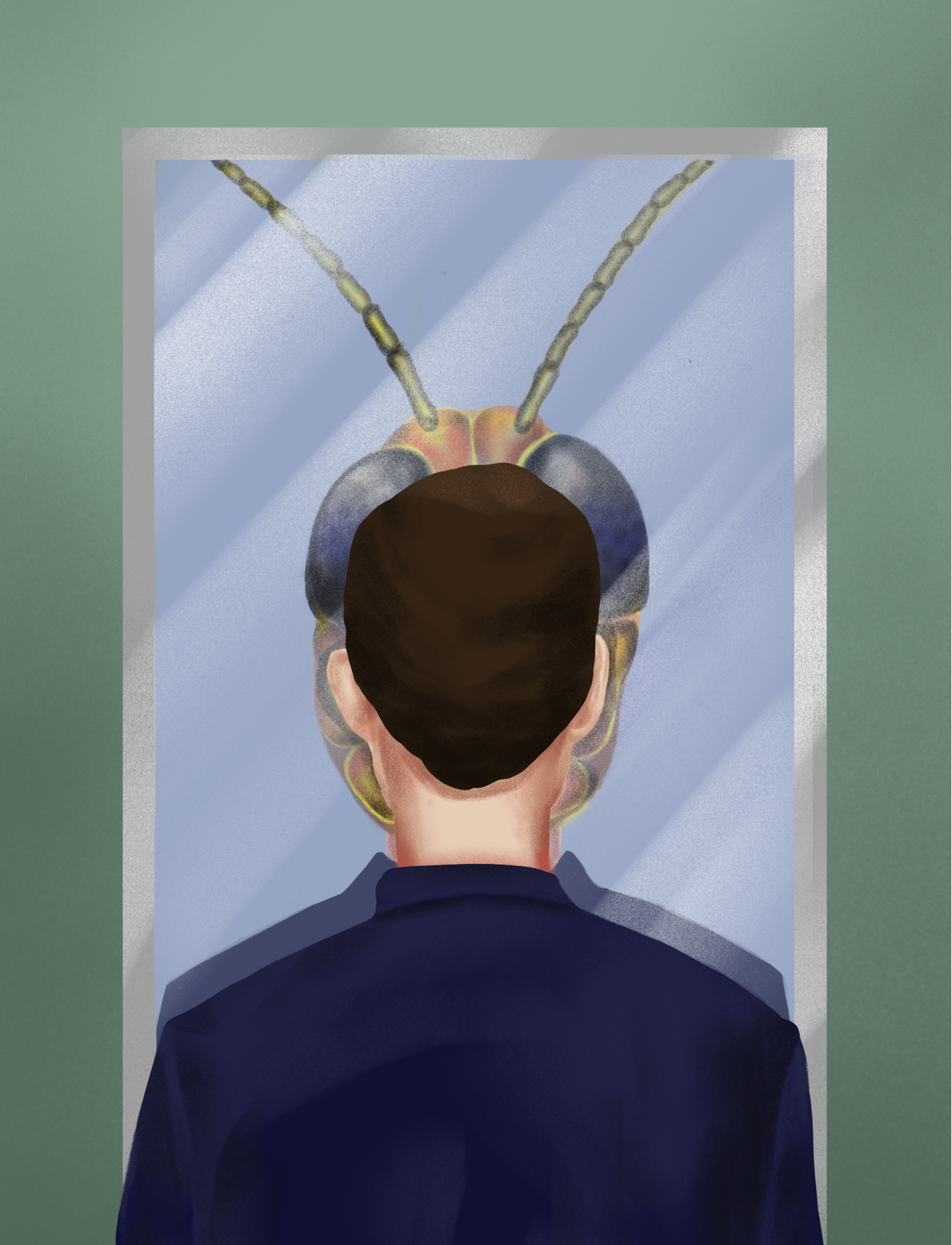

I’m in a contemplative mood again and despite President Biden having summoned a lot of his best attributes to deliver a rousing speech, there are a lot of contrasting tensions and emotions that obscure a clear view, like trying to see out your windshield while racing down a highway at night through a storm of bugs. In 1970, George E. Reedy, a former member of LBJ’s inner circle, published The Twilight of the Presidency. In it, he makes the following point:

The basic question is not whether we have devised structures with inadequate authority for the decision-making process. The question is whether the structures have created an environment in which men cannot function in any kind of decent and humane relationship to the people they are supposed to lead. I am afraid—and on this point I am a pessimist—that we have devised that kind of system.

Depending on a number of determining factors, your mood might swing between an acknowledgement of that point (marching in the street), and a simple need to be told everything is going to be okay by a symbol of supreme leadership so you can get back to mowing your lawn (watching the convention).

Day two was reflective out of necessity. We needed to scan the news outlets, interpret perspectives, and reflect on perceptions after the whirlwind 24 hours that preceded it. I start thinking about deliverance when thinking about Biden. Last night, with the bar’s television on mute, it looked like the fire in his eyes and fury in his face as he railed on in his speech seemed to scream out “Don’t forget me!” This morning, I read a piece in the Guardian, in which David Smith remarks the speech was “the culmination of a night that for Biden must have felt either like receiving an honorary Oscar or giving the oration at his own funeral”—likely a combination of both.

For as long as I, too, was a part of the millions who felt his age was a deciding (and excluding) factor, I still felt a hint of tragedy about his departure, about how, as Smith notes, “all of it shows the mercilessness of politics”—and entertainment in general—“and the mercilessness of time. How quickly the golden boy becomes yesterday’s man.” Even though Biden is a career politician, and many have gathered in the streets to convince us he’s a heartless agent of genocide, there is something to seeing an elderly person on stage have to manage the emotional weight of calculating everything they did that brought them to that point, and, with only the end left to look forward to, to comprehend one final, summative betrayal.

A quick recap of the day’s events:

We play catch-up for most of the day—and can’t catch up to the protestors at the Israeli embassy because we’ve learned it isn’t easy to track their movements, committed to communicating with each other via encrypted messenger apps as they are. We take a bus out to the Pulaski Park neighborhood in West Town, centered around a park designed by landscape architect Jens Jensen (who also delivered the nation’s first native plant garden to Union Park) and named for the Polish hero of the American Revolutionary War, Kazimierz Pułaski.

We eat at a cheap Polish dining hall called Podhalanka that reminded me of the Warsaw of the early ‘90s, when my dad took me to cafeterias in the city to experience the no-frills, egalitarian feel to “dining out” when the country was still the PRL (People’s Republic of Poland). The neighborhood was once a largely Polish enclave—Division Street was once known as the “Polish Broadway”—but Podhalanka is the only Polish business left. And on Friday, after 40 years, it shutters for good. We eat cabbage soup to rejuvenate our souls and share a batch of pierogies with a couple of Polish kielbasas.

We spend some time writing at the West Town Public Library, which sits on the ground floor of the grand Goldblatt’s Building, built in the late-Chicago School commercial style in 1915 to house the once famed department store founded by a pair of Polish-Jewish brothers, Maurice and Nathan Goldblatt.

We head to Chipp Inn, a cash-only corner dive on Greenview Avenue that dates back to 1897 for $3 beers and an opportunity to go over notes and check the news.

At 9:26 pm, we are at The Corner Bar in Bucktown, where we watch Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff step up to speak. The woman next to me, who’s probably in her late 30s, early 40s, says she was at the convention yesterday, thanks to a friend who works for a senator. Soon enough, the time everyone at the convention (not at the bar, hardly anyone at the bar is watching but O’Brien, this woman, and me) is waiting for arrives: the Obamas. It’s safe to say everyone has vivid, emotional ties to the Obamas (even if it’s simply linked to where they were in their lives when the American president was an eloquent young-ish man who represented hope and change). Yet, today, sixteen years later, I find myself slipping, like someone sitting on an ill-fitting stool, in and out of cynicism.

The circumstances of the 1968 Democratic National Convention were far more complex than this one (than any convention in recent history) and one reason is precisely because it put on public display the theater of mean-spirited, Machiavellianism characteristic of American electioneering that creates “an environment in which men cannot function in any kind of decent and humane” way. Today—and all throughout this convention—the speeches are characterized by simple, saccharine stories, using a kind of tell yourself it’ll all be okay and you’ll believe it language typically reserved for addressing children and personal crises. They are more often than not riddled with “cliches that men always use when they wish to conceal, rather than convey, thought.”

With President Obama in particular, calling Trump “the neighbor who keeps running his leaf blower outside your window every minute of every day,” is a wonderfully evocative image. But then you think, this guy makes hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of dollars to say just this kind of stuff. Then the brilliant stroke of the hand gesture juxtaposed with his facial expression while he made fun of Trump’s “weird obsession with crowd sizes” which cracks you up. And then you think of the banks and drones, oh lord, the drones, so many drones—increasingly a key aspect of his legacy.

Finally, since Biden was effectively forced to step aside, everyone has been applauding his incredible courage and commitment to the American people by “putting his country before his ambition.” But it’s so clearly a large swath of influential people gaslighting themselves to gaslight the world into believing a completely different narrative. Yes, “we do not need four more years of bluster and bumbling and chaos.” But when was the last time we weren’t submerged in a quintessentially American dose of bluster and chaos?

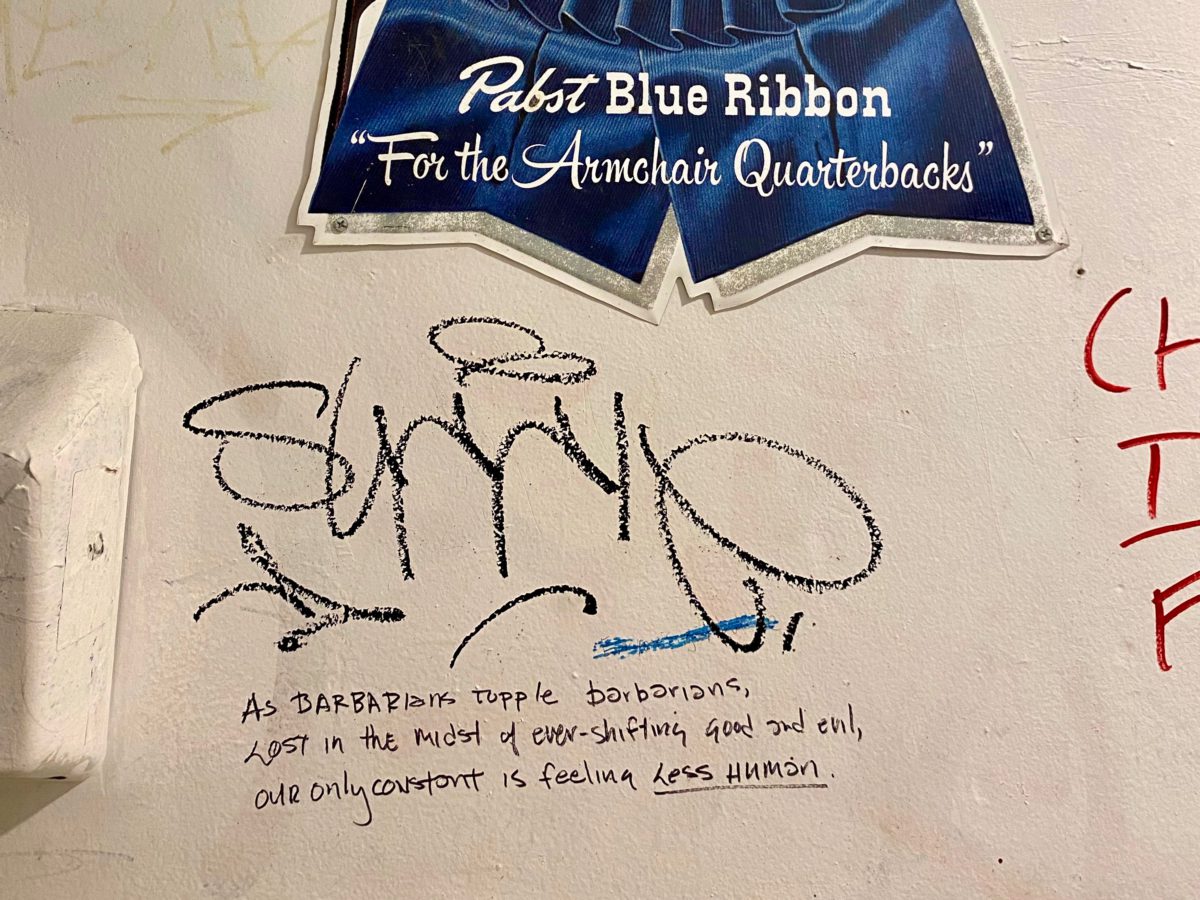

George Reedy ends his foreword to The Twilight of the American Presidency with a clarion call: “…one of the few historical principles in which I still retain faith is that an inadequate government will either fall or resort to repression. There is no reason to believe that the United States is exempt from the forces of history.” I get up to hit the head while most of us at the bar sing along to the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time.” On the wall above the urinal I read in all-caps black Sharpie: “As barbarians topple barbarians, lost in the midst of ever-shifting good and evil, our only constant is feeling less human.”

Sky O’Brien: Wednesday, August 21th, 2024

There’s no point getting upset about it. The ghoul just doesn’t know how to articulate himself. At least he can hump the air in front of the Christians. At least he can perform ten jumping jacks and run in circles around the pro-Palestinian protestors. At least he can dance. One day, with enough practice and a bit of pizazz, he might even learn to talk.

I am going to be optimistic. I am going to keep my faith in the First Amendment. I am going to keep standing outside the United Center, where thousands of Harris supporters are lining up to attend day three of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and I’m going to tell myself that the people protesting around them must be protected at all costs.

Like the ghoul. While it is not necessarily clear what he is protesting, his presence is charming, even affable. I don’t need to dwell on the particulars of his message. By his very nature, dressed in a skin-tight onesie that covers his body and his face with the graphic print of a gray human corpse, it is possible that he has simply come to the United Center to protest an historically troubling injustice: Death. He has brought a friend. Look, the ghoul is having a conversation with a woman dressed as an anime character. She has purple hair and is flying the flag of Hezbollah. Now she is flying the red flag of communism.

To join the fast-moving line into the DNC, a Harris supporter must pass the ghoul and the anime character, but they can ignore them by looking the other way. Ignoring the pro-Palestinian protestors takes more ambition. Standing next to the line, just before the first security checkpoint, the protestors have brought megaphones, and they’re using them with the same energy and composure that the Christians, just over there, are using theirs. “There’s blood on your hands,” a pro-Palestinian protestor says to the people in line. He’s wearing a red Landback flag like a cape. He continues: “Children are being murdered with weapons paid for by your tax dollars.” Harris’s supporters are blessed with hands, and they use them to cover their ears.

The message from the Christians is more subdued. “Attention, Democrats,” says a middle-aged man in a yellow fluorescent hoodie and long white socks. “God is getting ready to unleash his wrath on this nation, and we are not ready for it.” He says a lot more, but it turns out I can’t hear him. For a violinist has arrived, and so have a couple of ex-con Trump supporters, and now there’s a content creator yelling “We here at the DNC in Chicago baby let’s get it!” in front of a camera. He yells it about ten times before he’s happy. Luckily, the Christians have placards, so I don’t have to hear what they’re saying to receive their message. From left to right, I read: “The wrath of God abides upon the children of disobedience”; “Abortion is murder”; “Homo Sex Is Sin”; and “Trust Jesus.”

A man with a camera and a “Make America Great Again” hat has arrived. Without delay, he walks to the line of seated women campaigning for congressional candidate Tamie Wilson, all of whom are holding their own placards with worrying messages like, “A woman’s place is in the house, the senate, and the oval office.” The MAGA man wastes no time introducing himself: “Are you offended by this hat?” he says, pointing to his nice red hat, and holding his camera so it gets his face and the face of the woman he’s talking to in frame. Before he can hear the woman’s response, the MAGA man is distracted: The ghoul, full of life, is doing the worm on the asphalt.

While the ghoul is doing the worm on the asphalt, I talk to a guy who works for a “small news company.” I’ve been watching him film the arrival of congressmen and congresswomen and other special guests who get to cut the main line into the convention. Judging by the way he runs up to them and asks them about such things as genocide and weapons embargoes, he’s not applying for a job. During a dry stretch of VIP arrivals, when the only things to look at are the ghoul and the anime character sucking an imaginary penis in front of the Christians, I ask the guy what he thinks about everything happening in front of us. “Hezbollah is responsible for the death of US servicemen,” he tells me, and I find it absolutely impossible to determine what side he’s on, if he’s on a side at all.

I’m relieved when a man asks me if I want to buy three Harris-Walz 2024 pin-back buttons for $10.00. “Everyone needs a button,” he says in such a friendly and despairing tone that I almost reach for my wallet. But I have been standing here too long. I have been waiting for something to happen. Two blocks away, in Union Park, hundreds of protestors under the banner of the Coalition for Justice in Palestine have been rallying and preparing to march on the DNC once again. Sosnowski and I wondered if I’d find them here, breaching the fences of the United Center and resisting the thousands of police officers cordoning the streets.

When I walk away in search of Sosnowski, who left a little while ago to charge his phone, the ghoul is doing push ups in front of the Christians, the man with the MAGA hat is smoking two THC pens at once in front of the content creator’s camera, and the small party of pro-Palestinian protestors is reading the names of children killed in Gaza. Meanwhile, Harris’s supporters continue to arrive, streaming into the United Center for another night of fanfare, past the police, past the cameras, and past the nine or ten Ukrainians on the corner, all of them silent, all of them holding signs that say, “Victory for Ukraine, Victory for Democracy.”

Marius Sosnowski: Wednesday, August 21th, 2024

“See a crowd. I feel the mixture of tension and curiosity that is always the signal of something happening, and I hear shouting and see police cars.” —Mavis Gallant, Paris Notebooks

A line of police vans along Ogden Avenue. Cruisers spread out, lights blazing, blocking intersections. But what’s really striking is the police cordon, two rows deep, from Ashland Avenue at Maypole to Washington as it curves along the park and spills into Ogden. It is 7:53 pm, the sky is pale blue with the last dashes of sunlight receding to the west. O’Brien and I slow down and finally halt, curious and expectant.

The first bulwark we catch while walking north on Ashland is made up of the bicycle brigade. Suddenly, they mount in that particular way of theirs and ride off one-by-one, an ever-lengthening black and blue snake, onto Washington Avenue. North of Washington along Ashland a line of foot soldiers in their blue shirts and high-visibility vests stand at the edge of the sidewalk, another row of bicycles just behind them parked along the curb. In the park, the Palestinian flags continue to wave and dance and the chants are now, after a solid five and half hours, more of a low steady hum, hardly louder than the general buzz of the crowd.

It is not a massive gathering, but it’s not exactly small either. Maybe a hundred, a couple hundred tops. We stop on the sidewalk opposite Maypole street to talk to a couple of photographers just when the line of foot cops are called to attention and told to move out, south down Ashland, and east onto Washington. One of the photographers is flying solo, without a badge, while the other has his official press credentials as a representative of The Chicago Crusader, a local African-American weekly since 1940. All around us the clicking sound of bikes in motion.

We shoot the shit about where we’re from—the freelancer originally from Modesto, the Crusader a Chicagoan—and the Crusader warns us to have our wits about us if we’re not wearing press passes when things get heated. “The police’ll push you in with the others when it’s time to disperse. Bunch of journalists got locked up last night.” The march started around 5:00 p.m. and headed down to the United Center again, a couple blocks to the southwest, before returning to the park to continue rallying. I ask if there’s a curfew, and they say no, no curfew, so I ask about the double stacked bulwark. “It’s to pack everyone into the park,” the freelancer from Modesto says. Like herding. I ask if anything’s been heated, and they say not really, no violence or pressure from either side. (When we first approached, the freelancer looked like he was catching up with a buddy, a police officer.)

Eventually we part company and continue up Ashland to the L station, where we’ll catch a Pink line train into the Loop. Just before the stairs stands a grip of police officers who seem to be resting, joking, laughing. Someone at the bus stop is filming with their phone, yelling vitriol at a man in a chainmail, medieval battle costume, more or less in Palestinian colors. The cops shake their heads and laugh and another photographer on his bicycle says, “I’ve had enough weirdos for today.”

We first arrive at Union Park at 2:39 pm, after a hearty lunch at Al’s # 1 Beef in Little Italy and a train ride to the park where we overheard some college-aged people from SDS (Students for a Democratic Society, UIC and Milwaukee chapters) in protest dress (keffiyeh, mask, combat boots…) talk about recent events (“…he came away with bruised ribs…”). Everyone is amassing in the baseball dirt that’s surrounded by the bleachers where there’s a large banner and a podium.

O’Brien moves closer to the center of the flag-waving. It’s mostly Palestinians, who chat in Arabic. The men here are all well-built, and in their CJP (Coalition for Justice in Palestine) high-visibility vests and keffiyehs they look like soldiers. The air is anticipatory and somewhat tense around certain members of the press. One man with a gigantic flag walks around chanting “Free Palestine!”, occasionally speaking in Arabic with the CJP guys. I break from the scene and talk with some people at the RCA (Revolutionary Communists of America) table standing at the corner of Washington and Ashland. At:

3:16 pm, I’m sitting at the bleachers watching the crowd grow as people continue to file into the park from all directions, and different rhymed chants go out over the P.A. The police are all along the perimeter. I learn from a local that this is an unpermitted gathering, unaffiliated with Monday’s coalition, but one that is Palestinian-oriented—Chicago has one of the largest Palestinian populations in the country—with mosques helping bus in participants from the suburbs.

3:21pm, a troll with a large American flag breaks in and marches about the park in strange circuits, in and out of the group yelling “I wanna see this flag! How about the flag of our country?!?” Some pro-Palestinian protesters start following him with their flag. He makes it into the thick of things, just beside the podium and stops. He is surrounded. “How about flying the flag of my country?!?” he shouts. “This is my country and I want to see my flag!” “Fuck you and fuck your flag!” someone yells out.

“Please! Listen to your marshalls!” the P.A. roars, then conceivably the same in Arabic. “Do not follow the agitators! Please! Listen to us! Do not follow the agitators—that’s what they want you to do!” More Arabic. He’s outnumbered and outgunned but he’s damn defiant. He’s a Black man in a black suit with black sunglasses being followed by a few young white guys who have their phones out to record. Every so often another batch of pro-Palestinian protesters are goaded into following him, flags waving, and the whole things starts again. For someone who hates flags, I’ve never hated flags more than this.

3:40 pm I’m at the east end of the park, by the basketball courts. There’s a couple of pickup games and some kids shooting layups. Shades of Hey hey LBJ how many kids did you kill today? from the loudspeaker: “Genocide Joe is his name! Killing children is his game!” “Killer Kamala you can’t hide! Everyday a neighborhood in Gaza dies!”

3:56 pm I’ve regrouped with O’Brien. At the eastern edge of the baseball diamond a camera crew sets up while protesters continue to gather around the stage. Hundreds at this point. The reporter holds his microphone and practices his baseball swing. A few times. Good form.

We move through the crowd again and spot a man a couple dozen yards away shuffling along with a cardboard sign that reads “Help the Homeless.” For the two or three minutes I track him I don’t see anyone acknowledge him or his cup.

4:29 pm. Almost two hours of nonstop chanting. Their voices don’t seem to tire whatsoever. Helicopters circle overhead. Fringe groups at the park’s edges. The American flag man is standing near the RCA table—which has moved closer to the action—and it looks as though they’re having a civil conversation.

4:41 pm we walk to the United Center. I spot three Black men with black t-shirts that say “ExCons4Trump.”

4:45 pm. At the corner of Madison and Paulina everything is effectively cordoned off by police. Cars come and go to drop off DNC attendees. Badge and ticket holders—well-dressed in suits and dresses—file into a gated entryway on the north side of Madison. Police and security by the barricades handle all movement. A gathering of three or four pro-Palestinian protesters have set up a bullhorn directly next to the gates where DNC-goers wait in a slow-moving line. They have a bed sheet that says “Blood on your hands.” One of them lists out the name and age of a dead child, then the two standing either side holding the sheet chant “There is blood on your hands!” This will go on. Every now and then another one of them, with his own bullhorn and a “Landback” flag, will call out a few people in particular, or make conversation like, “You can be Black or brown and still support genocide! I know, it’s wild right?”

At the southwest corner of the intersection, someone plays a tenor horn along to a boombox playing popular hits by Stevie Wonder, Gotye, Earth, Wind & Fire, etc.

The DNC attendees are a diverse crowd, mostly Millennial and Gen-X-aged. Many of them are very good-looking and put together in a way that betrays their income bracket. The men all have serious faces, like they have a lot of investments; the women like they have a lot of important contacts. It’s almost a texture—or lack thereof—the rich seem to have, the smells, the anti-aging products, the sheen on their clothes. Out of black SUVs emerge sleek beings who exude a put-togetherness that would be almost beguiling were it not so haughty and inhuman.

4:55 pm a large, black Cadillac Escalade that is very poorly parked, blocks part of the crosswalk, and will not move. The driver and his partner stand by each taillight, hands clasped behind their backs. An OEMC officer yells at them: “Move your car! You can’t park here!” They say something to her and she makes a disapproving face. She goes to talk to a cop. The cop approaches the two men and again a close conversation takes place. His expression is one of reluctant acknowledgement. Another five minutes passes. I’m standing right by it. A woman and two children approach the Escalade and the door opens. It’s Rosario Dawson, accompanied by a bored-looking man who is not Corey Booker. She puts on a facemask and they are ushered into the central, “VIP” entrance, through barricades that are manned by two guards and three police officers, one in full combat gear.

5:07 pm, not four feet from us, marches in Senator Raphael Warnock through the center entrance flanked by a couple of officers in combat gear, a couple of men in suits trailing behind. The man with the bullhorn hops away from the three listing out the children and tries to get in Warnock’s way. There is a swift response from all forces. “Yo bro! You can end the genocide today! Come on, bro!” He is stopped at the barricades and he continues to call out to Warnock while security glower and tell him “get back in front of the gates”; how swiftly I spot hands grabbing ahold of the wooden batons.

5:09-10 pm Monday’s Christians arrive with the “Jesus Will Vomit You” sign, “Homo Sex Is Evil,” “Abortion is Murder,” and other Eternal Damnation signs. They set up a large P.A. system and get to work. I also notice there is a person with rainbow-colored piñata-textured tights who has been playing very strange, weepy music on an amplified violin. The L roars along behind us with regularity. Multiple helicopters above us now. The cacophony has grown to impressive proportions, itself a form of oppression.

5:17 pm the ExCons4Trump guys arrive. They get into a heated, yet civil, debate with a Black guy who has a DNC badge. The DNC guy is from Texas, and he tells them he knows all about oppression. The ExCons are from Chicago, and they know all about oppression. Views are exchanged, diatribes traded, platforms debated.

The leader of the ExCons says “Now I don’t give a flying fuck about either party. My interest is the fall of America, period. Do you hear that? The fall of America, period, and Trump represents the best opportunity to bring about the end of this system that has been oppressing us for centuries.”

The Texan responds by asking what he thinks about the impoverished, the undereducated, those who have no access to healthcare, the trans brothers and sisters, the disenfranchised youth for whom the Republican party’s entire platform is a threat, for whom Donald Trump would be a tragedy. They ask where he gets his news from.

5:31 pm the debate behind me rages on. A little later, a young white guy slowly creeps up to listen and the leader of the ExCons spots him—“Hey did Obama win by news or social media?” “Uh… social media?” the white guy says. “Social media! See?!”

5:46 pm. I am not cut from the same stuff I had initially thought I was. I feel woozy and out of sorts. My head is killing me—the P.A.’s will not stop, the music will not stop, the helicopters, the trains, the pissing contest of perceived pain playing out in this theater of chaos. Everything in America is converging in Chicago in an atonal symphony out of the darkest nightmares of a Béla Bartók and Steve Reich love child.

O’Brien meets me at a bar at 1515 Monroe street where I have learned two things: One, Chuck Schumer does not drink but everyone in his gang loves espresso martinis; and two, Bernie Sanders loves Outback Steakhouse, so much so he apparently called a former aide who lives in Chicago to help score a last minute table for a large group. I learn this from the bartender who is one of those wonders that brings everyone seated at a bar into one loose conversation. The DNC is on and it’s odd to know we watched most of those people walk into the building.

O’Brien is worn out too, I can see it all over his face. “The thing about these things,” he says, “is they’re always building up, and just when it feels like something’s about to happen, it diffuses.” But there is a relentless onslaught of stimulation. And it must be the bonds of partisanship, or ideological loyalty, or intense identification that keep these things afloat on a psychic, or otherwise purely adrenaline-infused level. It is a marathon that, were it not so tragic, or so comic, or so absurd from every angle, would be a feat of human strength riveting to watch.

Much later, under the cloak of another brilliant night, the sounds of sirens will continually break up the buzz and hum of the incandescent city streets near the Loop while tourists and couples and Chicagoans will gently stroll the lakeside. We take in Grant Park and try to picture the masses we witnessed multiplied by over 10, all over it, between its trees and benches and lanes, with a pressure and mutual fury so intense that pressed bodies would burst through plate glass windows. An American tragedy. Meanwhile, at the DNC, Coach Walz will tell a packed stadium, “We’re down a field goal, but we’re on offense, and we’ve got the ball. We’re driving down the field. And, boy, do we have the right team.”

Sky O’Brien: Thursday, August 22nd, 2024

On stage at the DNC, Eva Longoria is talking about energy. “The energy tonight isn’t just here in Chicago,” she says to the thousands of Harris supporters gathered inside the United Center. “It’s all across the country.” Suddenly, the blue screen behind her fills with eleven live streams from states like Wisconsin, Georgia, and Philadelphia where Harris supporters are hosting their own viewing parties of the DNC. “Say hello,” Longoria says to the DNC audience in front of her, and what happens is this: the audience in front of her wave their flags and Kamala banners at the audiences across the nation, and the audiences across the nation wave back. All of Harris’s America, it seems, is waving at itself through the bright blue screen.

What would make this moment even brighter is a nice chant, something fresh that everyone can say together, and Longoria gives one a go: “She se puede!” she yells, riffing on the Spanish “sí se puede” (“Yes, we can”). Everyone does their best, but the words fall flat. Luckily, there’s a Republican in the room. Adam Kinzinger, a former Illinois Republican representative, is bemused when he takes the podium: “I never thought I’d be here,” he confides. “But listen,” he says, smiling at the crowd, “you never thought you’d see me here, did you?” Everyone finds this very funny. Everyone laughs, in that kind of relieved way that people laugh when they survive a near-death experience. And when Kinzinger says, very seriously, “I’ve learned something about the Democratic Party, and I want to let my fellow Republicans in on the secret: the Democrats are as patriotic as us. They love this country just as much as we do,” the crowd finds its voice: “USA!” they chant. “USA!” “USA!” The USAs are loud, but you can just hear Kinzinger’s nervous little laugh, as if he’s remembering the people in front of him are not, in fact, Republicans.

Earlier in the day, I’d had a nervous little laugh of my own. Unconvinced that we needed to hear another “Free, Free Palestine” in the streets, Sosnowski and I decided to visit the Art Institute of Chicago. After a communal experience of 20th Century American art, we split up, and I found myself upstairs walking through the rooms of Medieval and Renaissance art. After looking at a couple of Virgin Marys, I stopped in front of Giovanni di Paolo’s paintings of St. John the Baptist, who famously said Christ was just around the corner. There, in one painting, I saw Salome kneeling in front of her dad, Herod, asking him if he wouldn’t mind chopping off St. John’s head. The way di Paolo had painted Herod, he looked a little dopy, and upset, as if he had a rock in his eye and he was trying to wink it out. It was the painting next to it, titled, The Head of Saint John the Baptist Brought before Herod, that made me laugh, not at the sight of John’s head on a golden plate, which looked presentable, but at the way di Paolo had painted the king: he had both hands in the air, he was recoiling, and he looked miffed, even anguished, as if he didn’t know why there was a head in front of him.

“And they,” Kinzinger continues on stage at the DNC, “are as eager to defend American values at home and abroad as we conservatives have ever been.” What he means, and what he makes clear over the next seven or eight minutes, is that Harris is a conservative. “Some have questioned the stance I’ve taken,” he says. But the answer, he says, is simple: “I know Kamala Harris shares my allegiance to the rule of law, the constitution, and democracy, and she is dedicated to upholding all three in service to our country. Whatever policies we disagree on pale in comparison with those fundamental matters of principle, of decency, and of fidelity to this nation.” Then: “Listen, to my fellow Republicans, if you still pledge allegiance to those principles, I suspect you belong here, too. Because democracy knows no party. It’s a living, breathing ideal that defines us as a nation. It’s the bedrock that separates us from tyranny. And when that foundation is fractured, we must all stand together, united, to strengthen it.”

Everyone in the United Center stands. In a few minutes, when Kamala Harris takes the stage, they’ll stand again. Everyone would probably keep standing, but it’s only polite to take a seat when the Vice President is speaking, and that’s what they do as she talks about “advancing our security and values abroad” and ensuring “America always has the strongest, most lethal fighting force in the world,” all of which certify conservatism’s new color: blue.

Marius Sosnowski: Thursday, August 22nd, 2024

“Give me Liberty to know, to utter and to argue freely according to my conscience, above all other liberties.” —John Milton

The last day of the convention. The coronation ceremony is all that remains, the moment Vice President Harris will say, “on behalf of everyone whose story could only be written in the greatest nation on Earth, I accept your nomination to be president of the United States of America.” Reflect on the feeling one gets in the knowledge that the matrix of global finance is disinterested in everything but profit and proliferation, programmatically monomaniacal like a virus. There is one last cumulative march on the DNC for Palestine, but neither O’Brien nor I feel up for it. The continued juxtaposition of the world outside the United Center with the one inside does a number.

When we start off into the city this final time, our mood is quieter, more pensive, the cicadas are playing their song on cue on another warm, remarkably clear day. I compare myself to a glass of fizzy water left on the dining room table of an empty house. The Art Institute of Chicago is the only tonic. We decide to walk there from the River North neighborhood after lunch at Schneider Deli.

It is a busy Thursday, with people shopping, working, traversing to and fro, and tourists filling the streets to the sounds of cars and trucks and horns and the smells of restaurant kitchens and alleyways and exhaust fumes and hot pavement. The architecture of Chicago is so renowned it has its own style—two even (the Chicago School and the Second Chicago School). O’Brien points out the “Corn Cobs” of Marina City. I notice a remarkable Moorish Revival auditorium that once could have been a house of religious worship but is, fittingly, a Bally’s casino. San Francisco is colorful but really it’s the white, gleaming city on the hill; Los Angeles is the tan of the Mojave basin and the Warner Bros. lot laced in smog’s foul pewter; Manhattan is the gray of its proprietary stone; Brooklyn is ruddy-brown; and New Orleans is the loamy, earthen hue of bayous and cypress. But Chicago, when you mix up its red brick, limestone, charcoal steel, and rust, Chicago is hard slate.

We turn onto Michigan Avenue and trek southward along the Magnificent Mile, an opulent thoroughfare linking the Loop to the Gold Coast of the Near North Side. O’Brien wants to show me the Chicago Tribune tower in particular, but it is easy to get distracted. He describes the Tribune tower’s defining feature—an assortment of tiny chunks of building materials from the wonders of the world and other historically significant edifices that are incorporated into the lowest levels of the 463-foot, 36-story, neo-Gothic hulk. I spot an elaborate mix of architectural styles across from me, with three priests—or soldiers?—in a gothic or Assyrian style at about middle height; a little bit lower a frieze depicts a tall, Osiris-like ruler overlooking a busy scene of horses and tigers and soldiers and chariots. “That?” I ask. “No, that’s Michael Jordan’s steakhouse,” O’Brien responds, referring to the steakhouse in the lobby of what is, in fact, the InterContinental Hotel, originally built as the Medinah Athletic Club in 1929. But I can see now, just across the street, a glorious and imposing neo-Gothic tower of limestone and glass.

Up close, the Tribune Tower looks like a climber’s paradise, a chunk from the Dome of St. Peter’s in Rome protrudes here, a stone from the Great Pyramid of Giza for your foot there; a small chunk to place your hand from Angkor Wat; a grotesque from the houses of Parliament; and here, a different texture, a block from the Old General Post Office in Dublin. There is a brick from Wrigley Field that, with a swish of yellow, looks like a hot dog, and above it a Fleur-de-lis from Notre Dame. We stand in Pioneer Court and admire the Chicago Tribune sign for a few minutes while the swirl of people go by, taking selfies and videos.

Just before the DuSable Bridge, I hear a gentle kind of music drifting in—something electronic and sanguine that sounds like vibraphones and other synthetic sounds—that I assume is meant to be soothing but is kind of unnerving, as though someone from Burning Man were dragging windchimes along your body. We turn and see an RV for Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.,’s campaign parked in the little driveway to Pioneer Court, “@Kennedy24BusAcross America” emblazoned across the side, “The Remedy is Kennedy” on the doors. It slowly inches forward and the hippie behind the wheel waves at all of us. Serendipitously, the sleek, gunmetal blue, all glass 100-story Trump tower, with his name slapped across the front, like all his towers, in massive chrome, looms behind. Couldn’t you almost picture it, in mad, fever dream America: a Trump / Kennedy ticket?

We cross the Chicago River and come to the corner of East Wacker Place. Designed by the Burnham Brothers (sons of renowned Chicago urban planner Daniel H. Burnham) and built in 1929 to house a major chemical company, the flat black granite base, the dark green and gold terracotta bricks, and the gilt accents of the intoxicating Carbide & Carbon Building is to me the most remarkable example of the Art Deco style, the glittering realization of the dream. The Chrysler Building is a marvel, yes, but this is something else entirely. Los Angeles’s Richfield Oil tower was magnificent (although it was much shorter and has long since been demolished), as is Manhattan’s American Radiator Building, both clad in all-black. But the Carbide & Carbon, shimmering here in juniper green like snakeskin from the sunlight reflecting off the glass surface of the citizenM hotel tower across the street, is the apotheosis of the American Art Deco skyscraper, so much beauty in the service of the sinister. These are immovable mirrors, intractable snapshots of states of mind throughout time.

Almost to the Art Institute, we hear the familiar chants for a Free Palestine, then make out a row of police and the dancing, bloody hands of cardboard Netanyahu. The protesters, some two or three dozen strong, are compressed into the opening of an alleyway adjacent to the Chicago Cultural Center. Nobody really stops. A few cars honk. We walk to the Washington Street end of the neoclassical structure—full of intricate relief work and ornamentation in an Italian Renaissance style—and read it is closed for a DNC event. I try to simply look through the window and am told tersely it is closed, to step back. “We’re not political agitators,” I tell them affably, “mere architecture aficionados,” and I try to point the lobby mosaics out to my co-correspondent. “I’m just saying if you get too close they”—meaning the cops three yards away—“are going to get involved.”

We go through a security checkpoint with metal detectors to enter Millenium Park and walk over to the Art Institute. There is no line.

American Art 1900-1950. Nighthawks did not travel to the Whitney for Hopper’s retrospective last year. The emptiness is even more stark up close, the details in the mundane objects more striking, the reflections in the windows across the road from the diner echoing the loneliness.

There are paintings by Peter Blume, Kay Sage, Norman Lewis, Arthur Dove, Archibald Motley, Georgia O’Keefe, Walter Ellison, Marsden Hartley; the recognizable forms of modernist painters are layered in mystery, ambiguity, vibrancy, and fantasy. I tour the halls piqued by vulnerability. I can’t place exactly why. The thousands of chants, thousands of bombs? The thousands-upon-thousands roar of applause? It’s a strange time for a first visit to Chicago, and strangely comforting to visit this museum, as if a sprawling complex filled with priceless, often ill-begotten art could somehow provide me with the unquestioning embrace my nerves have asked for.

From 1900-1950, I go further back. To the reassuring, clean lines of a Shaker sewing desk. To the ghostly portraits of my beloved Whistler, compact and gleaming. From there I pass through the arts of the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine worlds—those remarkable transmissions across the ages using only form for language—to the Chagall Windows. When Chagall worked on the America Windows for the United States bicentennial in 1976, Israel was still in the wake of the Yom Kippur War; the movement to settle the West Bank, through Gush Emunim, still nascent. On March, 30, 1976, local Arab leaders imposed a general strike to protest the land grabs, henceforth commemorated as Land Day. In 1977, when the windows were gifted to the Art Institute of Chicago, Israel’s center-left Labor Party lost for the first time in its history to the populist, arch-conservative Menachem Begin and his Likud.

Chagall’s hypnotizing stained glass panels tell the story of America through music, painting, literature, architecture, theater, and dance. At the bottom of one of the last panels, a menorah gleams under a figure seemingly in oration. I think of the Yiddish theater, and of my Polish-Lithuanian great-grandmother’s humor, her tragi-comic, earthy expressions, like “Man plans, God laughs” (Człowiek się męczy, a Bóg się śmieje). I feel bathed by Chagall’s blue and somehow delivered. “To me, stained glass is the transparent wall between my heart and the world’s,” remarked Chagall. “It must come alive through the light it receives.”

Does my lover feel what I feel when he comes near?

My heart beats so joyfully

You’d think that he could hear

Wish I knew if he knew what I’m dreaming of

—Debbie Reynolds, “Tammy”

So how to close off this dispatch—this string of dispatches? It is much easier to deal with inanimate objects than with the murky, used bathwater of human motive, human behavior. We stop by the Hilton for a drink and a snack. Our server asks us if we’re going to the DNC watch party at Soldier Field. Without actual plans for the Harris acceptance speech, why not? At dinner in River North, in the shadow of the Merchandise Mart—once the largest building in the world—we learn Soldier Field is beyond capacity.

Back at the hostel, I fill a tupperware container with ice, grab a Coca-Cola from the vending machine, and crack open a pint of Jim Beam. We listen to the speeches, we watch the sea of rapturous faces, waving American flags, note the vertical “Kamala” signs dancing wildly, like all the signs during these four long days, and admire the neatly compiled “key points” compiled for every speaker, like “Son of Latino immigrants” and “Growing up, dreamed of becoming an ESPN anchor.” Hunter Thompson’s famous words from Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas spring to mind: “There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning,” and I try to imagine what that must have felt like. Si monumentum requiris, circumspice (“If a monument you seek, look all around”).