Editor's Note: With Brazilians facing a vital second round presidential election at month's end, we thought it appropriate to present the following dispatch from Rio de Janeiro. Our correspondent, whose intimacy with the Marvelous City goes back to childhood, offers the following impressions of Rio under Bolsonaro, captured earlier this year during his most recent trip back.

[drop-cap]

The last time I was in Rio de Janeiro I found myself at the Sambadrome Marquês de Sapucaí taking in the samba-enredos of what cariocas justifiably call “the greatest show on earth.” I watched as the samba schools paraded in a spectacle of the senses—joyous, alive, and oblivious to the pending pandemonium of the virus. Foreigners typically notice the sexual overtones in the performances, missing the politically charged themes and lyrics, like “A Verdade Vós Fará Livre” (“The Truth Will Set You Free”) by the Mangueira school which told the story of Jesus Christ in a contemporary Rio slum. In an open jab at President Jair Messias Bolsonaro, its verses denounced “Messiahs holding guns.” Another school, the União da Ilha do Governador, sang of the unity of mankind before life and mocked “opportunist discourse, greed, and hypocrisy.” Fused to the 4 a.m. beat of a hundred thousand hearts, and downing a healthy dose of vodka Redbulls, I believed that the Brazil I had known as a child lived on. I believed that the election of Bolsonaro had been a regretful, albeit temporary, lapse in judgment.

Two years later, strapped in my seat as the A330 approached Galeão airport, I lusted for a soundtrack. The entertainment system had a paltry selection of Brazilian music. From the album Toquinho Cantando - Pequeno Perfil De Um Cidadão Comum, I clicked play on “Alegoria Das Aves” (“Allegory of the Birds”). Outside my window the morning sun lit the forested mountain peaks and the vast metropolis below. I was coming home to the city of my mother tongue—the city of poetry, of syncopation, of the melancholic smooth tones of Bossa Nova. The 250-ton aluminum bird touched down to “Entre a Loucura E A Razão” (“Between Madness and Reason”).

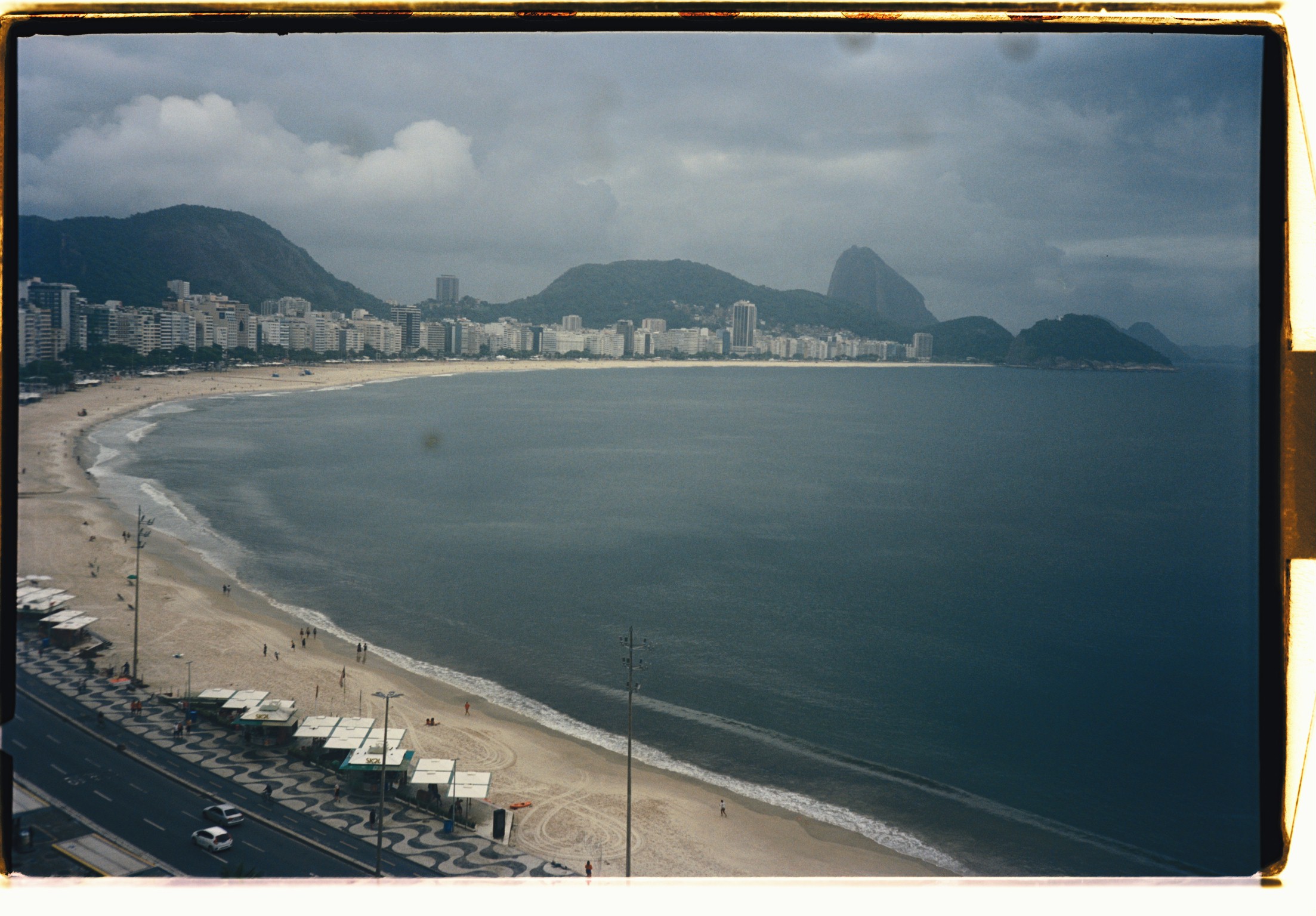

I ordered a fried egg breakfast at an understaffed hotel in Copacabana and eavesdropped on a family behind me. The fleshy matriarch pulled out a blister pack of pills while her young daughter scooped up a sugary pudding. A despondent-looking husband and the child’s impassive grandmother looked on.

“Does anyone want some?” the mother said, as she pressed a pill into her own hand.

“No.”

“It puts me in a good mood. Don’t you want to be in a good mood?”

She washed the pill down with a watered-down orange extract.

Pan-pan. Bromazepam. Clonazepam. Some form or other of pam. Once upon a time, this kind of medication was a stigma, but Brazil has risen to become the largest consumer of clonazepam—which is used to treat anxiety, panic disorders, and seizures—in the world. The 80% spike in sales during the pandemic came atop a long-term trend. Brazil is now the world leader when it comes to anxiety disorders. Whether this is a consequence of addiction, politics, or the constant fear of violence is up for debate. Likely, it’s a blend of all three. But pills eliminate neither crime nor hunger.

...I believed that the Brazil I had known as a child lived on. I believed that the election of Bolsonaro had been a regretful, albeit temporary, lapse in judgment.

Outside the hotel, skeletal figures roamed the streets. Mothers slept with their children on the sidewalk under fig trees decorated with orchids. At the tourist stomping grounds along the Copacabana and Ipanema beaches there was no peace—every minute a beggar passed through disguised as a seller. Children begged for a bite to eat outside of the butecos. Inside, people downed savory petiscos with copious amounts of beer, and, as their waist measurements testified, in ever greater quantities.

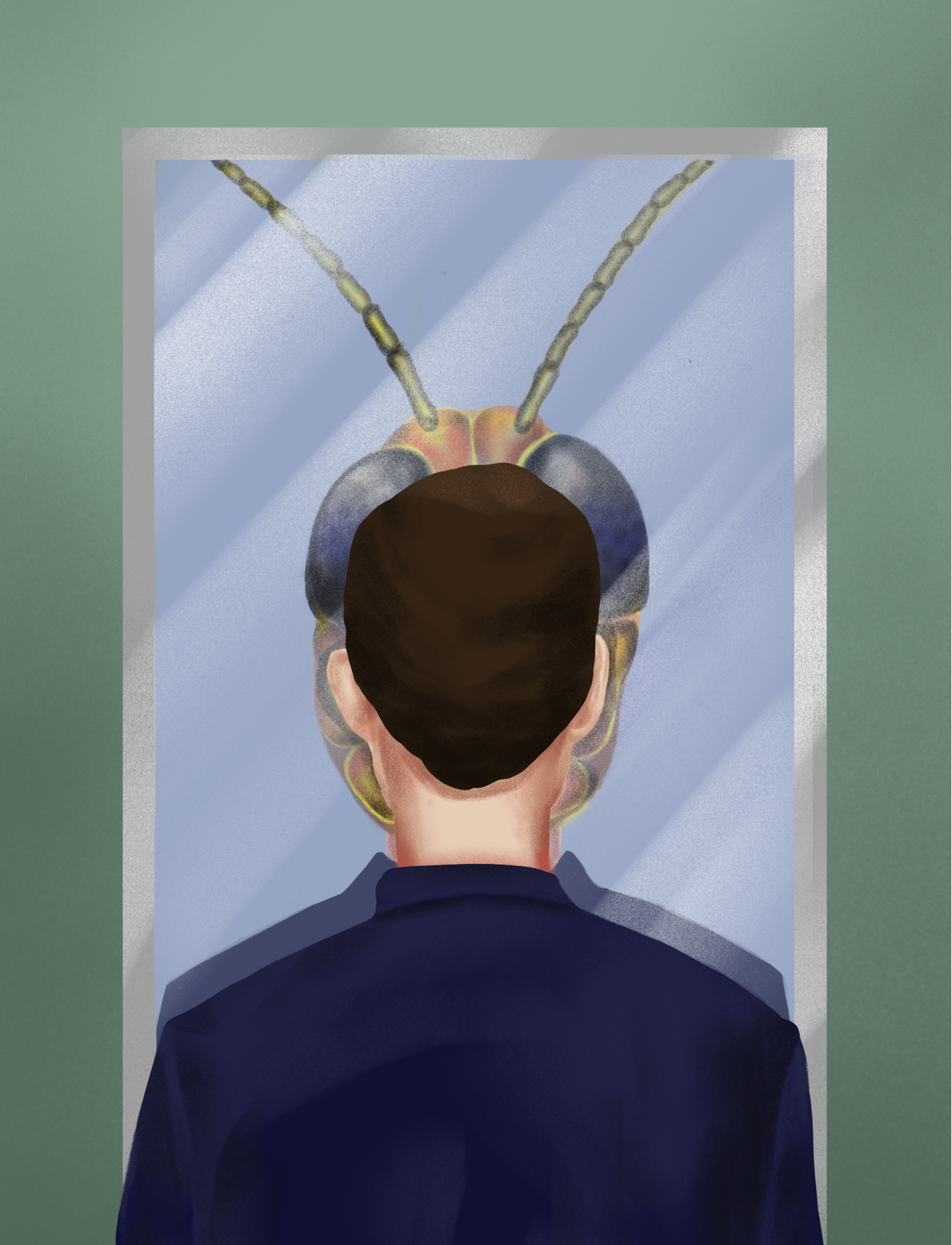

In my room I turned on the news. I was taken aback when a reporter pointed to a chart and declared with pride that for the first time in twenty years the Republic had exported more commodities than anything else combined—51% to be precise. From an industrialized nation to a commodity provider, so much for order and progress. The pandemic was coming to an end, but I felt as if I had returned to Rio in a broken time machine, and the past I had landed in was a dreamlike parody. I was no longer sure I could trust my senses or my memory. The country seemed corrupted by a latent sadomasochistic impulse.

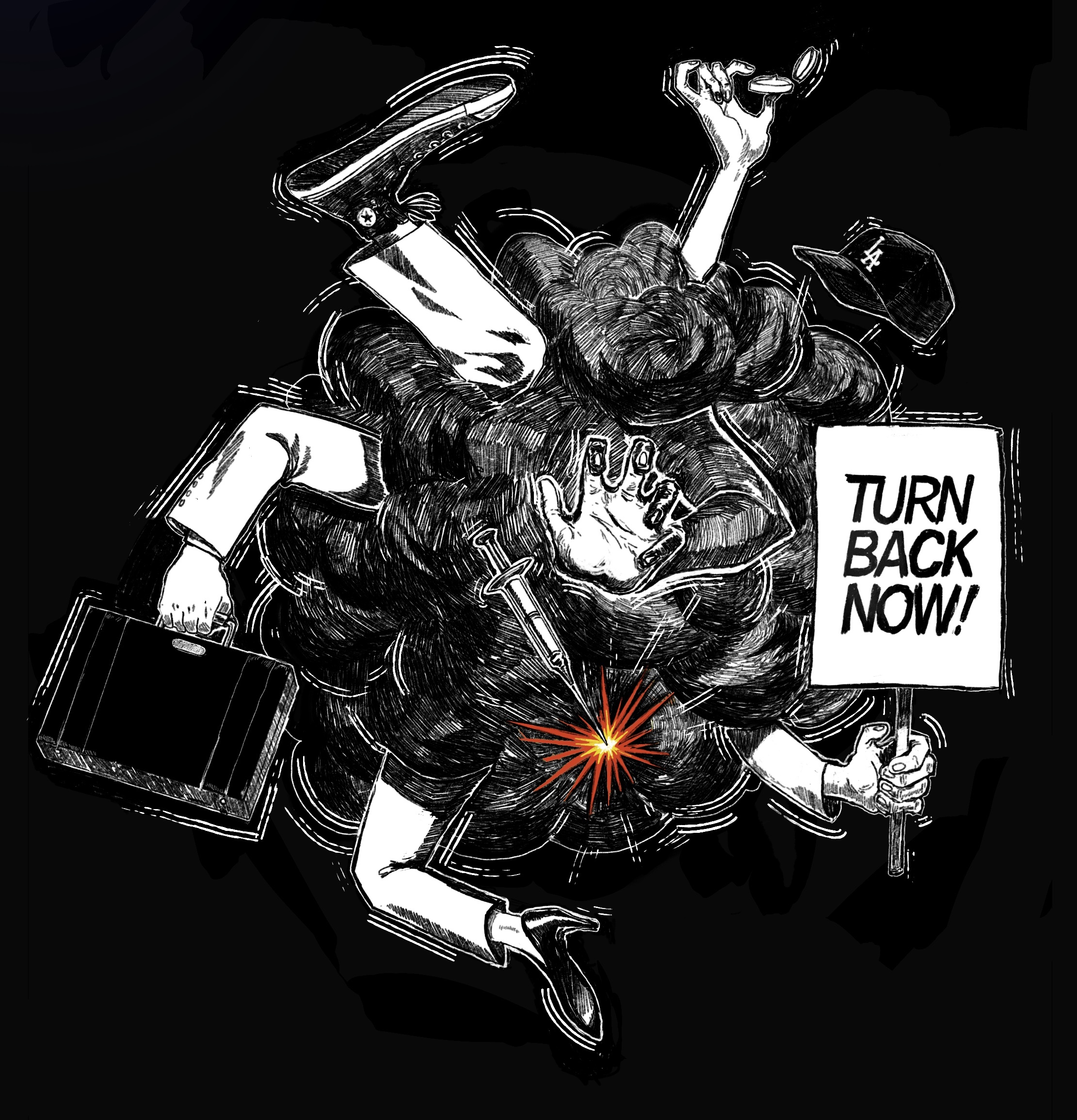

I spent the days bolting across upper- and middle-class bairros in worn down Ubers. The cars’ tires seemed ready to peel off and, for lack of a seat belt, I held on to the handles above the window. Everywhere I saw a potential fanatic Bolsonarist waiting to enter into a shouting contest, waiting to boil over and finally put their shooting range experience into practice. I stayed quiet.

Uber was the cheapest way to get around. Back in 1994 the Brazilian Real used to be even with the dollar. In 2011 it was 2:1. Now I could buy five Brazilian republics for the price of one American president. Five empires for a horse. Inflation was a problem in the 90s, but this newer trend was a reflection of capital flight—a loss of hope. Built in the 1950s, Brazil’s capital, Brasilia, had been modeled on an aircraft taking off. Rapid industrialization suggested imminent prosperity, but the coup in 1964 put a stop to that. The 2000s seemed to rival that sentiment of boundless hope. In 2009 the Economist famously announced “Brazil takes off.” If so, it flew directly into the impeachment of Dilma Rouseff seven years later. “Brazil is not a serious country,” De Gaulle is reported to have said, but it is unclear whether it was De Gaulle or the Brazilian ambassador he was meeting with who uttered these words. Faced with so many aborted takeoffs, Brazilians have perpetuated the myth in regular outbreaks of self-doubt.

The threat of hurtling out of an Uber window at 100km/h was palpable, but widespread crime brought the reptile brain to life. As comfortable as a soft linen dress shirt and a pair of dapper sunglasses may have been, style makes you stand out in a country where class markers are best saved for the inside of a private chopper. To survive in the Marvelous City you have to do as the cariocas do: don’t stand out, and don’t trust anyone. Sometimes even that isn’t enough. Late at night in a bar in Barra da Tijuca, a safe area close to the beach in an upper middle-class neighborhood, I was having a drink with a lawyer when he pointed out a man in a blue hoodie with thick leather gloves. The man seemed to be waiting for something. Only one type of person wears a hoodie and gloves in the tropical summer. The house where I had lived as a child was within walking distance. So too the constructivist school where I first learned the alphabet. As I imagined what it would be like to be hit by a stray bullet, we moved to the bar next door. The lawyer left to inform the police. When the cops arrived, the blue hooded man was gone.

Thinking that museums might provide some comfort, I made my way to the Museum of Tomorrow, designed by the Valencian starchitect, Santiago Calatrava. Opened in 2016 in anticipation of the Rio Olympic Games, the hopeful edifice looks like a gigantic futuristic liferaft, sited north-south on an old pier at the edge of Guanabara Bay. There was a distinct lack of vegetation and the heat was infernal. The surrounding turquoise pools were filled with rust from the iron ore that blows from the shipyard across the bay. In early 2022, the theme of the main temporary exhibit was “Amazonian Futures.” Despite standing meters from a ticket booth, the only way to buy a ticket was through my smartphone. The website did not accept my foreign card. On a five-meter placard the logos of the exhibition’s main sponsors glared white on denim blue. Apparently Shell and Bayer were proud defenders of the future of the Amazon. I turned on my heel and trekked away across the hellish heat.

Soon I found myself in a stately refuge. MAM, the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art, a 1950s modernist concrete structure designed by Brazilian Affonso Eduardo Reidy, remained a temple to the hopes of that era. Here was a markedly different symbolism from that of the Museum of Tomorrow. A lush garden rested behind the majestic structure: a small oasis open to all in the feverish city heat.

There were more shelters to be found. In central Rio, old areas had welcomed new patrons. At Bafo da Prainha, old Brazil met a progressive mindset. In shorts and t-shirts, people of every forward-thinking persuasion gathered around flabby wooden tables, foldable chairs, and sunburned plastic stools. Women with colorful hair made out as a man in his thirties sold pins stamped with anti-fascist themes and anti-Bolsonaro dreams: In the upcoming election, they would certainly vote for the return of Luis Inacio Lula da Silva. Around this crowd stood the façades of eclectically restored buildings from the turn of the 19th century. I only visited Bafo da Prainha once, and my night was cut short by a torrential rain that scattered the crowds and inundated many of the roads leading out.

Some days later I found another sanctuary nearby. Halfway to the top of Santo Cristo, an old hilltop neighborhood in the port region, was Bar do Omar. Renovated by a business savvy anti-Bolsonarist who made a point of selling beer called “Lula Livre,” the bar had a spectacular view of the city. On the way up the Uber driver thought he had entered a favela, by reputation and the connotative steep incline. Aesthetically it was not far from that of hilltop neighborhoods in Lisbon.

By then the Hunga Tonga eruption had made its way to Brazil. A dramatic tropical sunset turned purple indigo and Russian violet. Inside the bar, a spray-painted mural showed the former president Lula with a beard of flowers. Among the brimming life sat known local politicians of the broader left. Every once in a while, someone stopped to take a selfie. The speakers blasted leftist oldies louder and louder as the night progressed. After the bar closed, a dozen Uber drivers canceled upon seeing the pickup point. We had to reassure them that it was safe.

As the omicron variant began to threaten daily life in Rio, I packed my bags. On the way to the airport, we passed a car that had burst into flames on the other side of the highway. Close to the terminal, traffic slowed. A group of military police holding automatic rifles signaled every car to slow down. The rifled cop raised his barrel straight at the driver’s isofilm covered window ahead of us. The cop took a step back. The windows rolled down. His squad peeked in and let the car pass. Our turn. Our lights came on and the windows buzzed down. The bullet path crossed each one of us as they scanned our faces and finally let us through.

As a child, I had a neighbor who was murdered. He had a mansion on our street. Whether it was his or his lover’s, no one can agree, even after all these years. But he was killed—gunned down on his motorcycle on the way to his girlfriend’s. His nickname was Maninho and he was a criminal. His brother, Bid, was killed in 2020 in a similar trap. Now, on my way out of the country, I heard that Interpol had arrested the brainchild of Bid’s assassination in Colombia. I wondered if anyone had ever caught Maninho’s killer. As I stood in the check-in line, two detectives in short sleeved shirts and jeans, badges firmly hanging from their necks, approached the serpentine formation. One of them held some papers. I looked back at them as they scanned everyone in the line. Like a child I toyed with the idea that they were after me—a superspy on the run. They remained for a while, and then left.

The plane took off and a heavy rain commenced. From a window seat I watched the wind roar against the wing. Lightning flashed every other second in the distance. Ten thousand feet, twenty thousand, thirty thousand and we were still sailing through an anchor gray sky, the wingtips only visible in flashes. The plane veered west, away from the Atlantic and further into the country. At thirty-five thousand feet, still nothing but a choppy ride and darkness. To think that the sky could hold so much water at such altitude. Kilometers of water ready to plummet towards the ground. I imagined the deluge ahead. After a couple of hours, we turned east again and as soon as we passed the bay where Cabral first made landfall, the sky cleared and the seatbelt signs went dark. I shut my eyes and slept. I do not remember my dream. It was all quiet. Three weeks later Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine.