In AD 1000 the Aurelian walls of Rome, built to guard and protect a glittering million-city in the 3rd century, encircled a sprawling wasteland with a population of about 25,000. Riotous and dissolute, the millennial Romans lived amid surroundings for which the word “surreal” might have been invented. Colossal wrecks like the baths of Caracalla and the Colosseum itself towered above the dismembered statues of dead gods and defunct emperors, while innumerable “shapeless and enormous fragments” overawed the hovels of the living. As Gibbon puts it, “The city descended from the hills to the Campus Martius.” The Forum was an enclosure for pigs and oxen. Visitors cautiously navigated past the dung heaps and debris that choked the streets of the former “mistress of the world.”

The city’s past, as it existed in the minds of the Romans, was as jumbled as the cityscape. Pilgrims were told of how after the Flood Noah and his sons Jason, Japhet, and Camese had voyaged to Italy and built upon the seven hills, and pointed to wondrous things like the uncorrupted body of the giant Pallas, slain by Aeneas—sights which made them shudder, “the heroes of the old city being the demons of the new,” as E. R. Chamberlin writes in The Bad Popes (1969). The history of Rome, as it had been told by Polybius, Livy, Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius, was effectively lost, replaced by a fantastic farrago of Virgilian, mythological, and biblical elements. If, as we are told, a time traveler from Augustan Rome could easily have found his way around old Rome, though appalled by its conditions, far more bewildering would have been the Millennium’s geopolitical arrangements—a world turned upside down.

After a prolonged time of troubles beginning in the mid-2nd century, in which the whole edifice of Empire was shaken by disunity, “barbarian” invasions, and an interminable war with Persia (in 260 the luckless emperor Valerian was captured and kept captive for life by the King of Kings, Shapur I), Rome righted itself under a new and more adaptable power elite, which by 350 prided themselves for living in the Age of Restoration. With the new class in charge, the mystique of Empire was adapted to Christianity in the East, and lived on in the Latin West even after its “fall” in 476, when Augustulus Romulus, the youth reigning in Ravenna, was deposed by the German commander, Odoacar, and sent off to a luxurious exile on the Gulf of Naples.

The past changes more than the present, as Robert Lowell once said, and the distant past changes more radically than the recent. The Late Antique World, c. 150-750, took on a new aspect during the 20th century, especially during and just after the First World War, which aroused an interest in the rise and fall of past empires during the Age of Dictators in Europe, leading up to the Second World War; and continuing during the “long twilight struggle,” as John F. Kennedy called the Cold War. Was there a figure in the carpet?

In Medieval Cities (1925), the great Belgian historian Henri Pirenne maintains that the Roman Empire had “one outstanding general characteristic: it was an essentially Mediterranean commonwealth.” Aging, it became even more of a maritime empire. Rome, the old capital, was inland; Constantinople, the new, was a seaport. (So was Ravenna, although its harbor eventually silted up.)

In the sixth century the emperor Justinian and his formidable consort, Theodora, had presided over the Reconquista of Italy, Africa, and Spain from the Goths and other Germans. While the Romaioi in Constantinople might boast that the Mediterranean was once again mare nostrum, “our sea,” Pirenne argues that it had never really ceased to be a Roman one and would remain so for another century. The ancient Greco-Roman commonwealth lived on in the material realm of law and trade, and flourished in the spiritual: missionaries dispatched from Marseille and Italy brought the Christian gospel to heathen Ireland and fallen-away England.

“The Empire was far from becoming a stranger to the lost provinces. Its civilization there outlived its authority.” Justinian’s reconquests were too far-flung to be maintained, and prophecy told of a last emperor to come before the Judgment Day. But at the beginning of the seventh century, thoughtful observers in the City, as Constantinople was known, might reasonably have expected the commonwealth to endure for another thousand years.

It is still disputed whether the Muslim commander, Amr, ordered the burning of [Alexandria’s] famous library, or merely the destruction of its book-copying industry, because the Koran had made other books superfluous.

Who in the City could have anticipated the rise of an armed prophet in the Arabian desert who would unsettle all the known world? As Philip Hitti writes in his History of the Arabs (1951), anyone who had the audacity to prophesy such a thing “would undoubtedly have been denounced as a lunatic. Yet, that is exactly what happened.” In his lifetime, Muhammed had pacified and united the peninsula; he had also anticipated a universal Islamic domain, an all-encompassing House of Peace. In the century following the Prophet’s death in 632, Muslim armies would spread Islam’s dominion west to the Pillars of Hercules on the Atlantic and east to the frontier of China. Not coincidentally, (even providentially to the faithful), their earliest conquests were at the expense of Byzantium and the Sassanid Persian Empire; these perennial rivals had waged a hundred-year war, concluding in 628 with the utter defeat of the Persians, having meanwhile exhausted and enfeebled both.

In 628 the emperor Heraclius and the Persian Kavadh II were among the princes of earth who received a letter from Muhammed, who announced himself as the “Prophet of God,” bidding them to convert to Islam for the sake of their earthly kingdoms and immortal souls; other recipients included the rulers of Ethiopia, Oman, and Egypt. Heraclius coolly dismissed, and Kavadh II angrily berated the Prophet’s messenger. More thoughtfully, Tai-shung, the reigning Tang emperor of China, gave the Prophet’s emissary a polite reception, and encouraged the construction of a mosque in Canton (now Guangzhou), which still stands.

In the Middle East, for centuries Byzantine territory, the end of antiquity came with cataclysmic abruptness. The Monophysite Christian majority opened their gates to the invaders. “The overtaxed, persecuted heretics made no attempt to preserve the Imperial dominion,” Sir Steven Runciman writes. “In Syria and Egypt alike they welcomed the change of masters, considering the theology of Islam closer to their own than that of Chalcedon. Only Alexandria resisted.” The siege lasted fourteen months, during which emperor Heraclius never sent relief; and when it ended, the “last stronghold of Hellenism,” had fallen. It is still disputed whether the Muslim commander, Amr, ordered the burning of its famous library, or merely the destruction of its book-copying industry, because the Koran had made other books superfluous.

“Though they had no intention of destroying [Alexandria], they destroyed her, as a child might a watch,” E. M. Forster writes. “She never functioned again properly for over 1,000 years.”

Constantinople was menaced by Muslim arms as early as 667, and endured a harrowing siege in 717-718. But the Theodosian walls held, the Arabs froze and starved in the Thracian winter, and the Empire harassed them with Greek fire, Byzantium’s version of napalm. In the West, Islam’s conquests looked about to be extended from Spain beyond the Pyrenees until the Arabs were repelled by the army of the French prince Charles Martel, at the Battle of Tours in 732. In a famous passage, Gibbon imagines an alternative history:

A victorious line of march had been prolonged above a thousand miles from the rock of Gibraltar to the banks of the Loire; the repetition of an equal space would have carried the Saracens to the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland: the Rhine is not more impassable than the Nile or Euphrates, and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without a naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.

Such a catastrophe might have been averted, but the essence of the ancient regime—which was based on sea power—was gone. Encircled by Muslim conquests, what had been the Roman Empire’s inland sea had become part of Islam’s vast domain, and the waters of the Mediterranean, which had been free of piracy under the long Pax Romana, was at once given over to corsairs, as they were now called. In any case, the effect was forever to disrupt age-old patterns of culture and commerce, as Pirenne tells:

Their fleets sailed [the Mediterranean) in complete mastery; commercial flotillas transported the products of the West to Cairo, whence they were dispatched to Baghdad, or pirate fleets devastated the coast of Provence and Italy and put towns to the torch after they had been pillaged and their inhabitants captured to be sold as slaves.

In contrast to Islam, which had become expansive and cosmopolitan, the Latin West was forced for the first time to rely on its own resources. The Frankish Empire, hitherto marginal, became “the arbiter of Europe’s destinies.” In the space of a page Pirenne gets to the essence of the famous thesis he would elaborate in his posthumous book, Mahomet et Charlemagne (1937), and epitomize as: “Charlemagne, without Muhammad, would be inconceivable.”

For all of its decline and fall, Rome remained a prize, a destination, and place for history to be made. On Christmas Day, AD 800, in St. Peter’s, the grandson of Charles Martel was crowned emperor of the West by Pope Leo III; having intended to crown himself at some opportune time, Charlemagne was startled by Leo’s proleptic gesture, but accepted the obeisance hitherto given only to the emperor in Constantinople. Unfortunately, its new overlords in Gaul were too far away to secure Rome from Muslim incursions.

In 846, launching from their base in Sicily, Saracen raiders sailed up the Tiber to Rome, where St. Peter’s on Vatican Hill, unprotected by Aurelian’s wall on the opposite side of Tiber, was looted of its treasures. Arab traders trooped their captives in ports like Taranto, where Bernard the Monk claimed to have seen 12,000 enslaved Italians being herded to a waiting fleet for shipment to Africa.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, the papacy had become a battered trophy for Rome’s aristocratic families to contend for. The suspiciously short reigns of elderly nonentities alternated with the stormy ones of young scions. John XII, elected to be the vicar of Christ in 954, at the age of sixteen, was a headstrong, libidinous youth, who lived up to the legendary vices of his family, the Theophylacts. His great-grandmother Theodora, had her lover, the Bishop John of Ravenna, installed as Pope John X, having previously secured her influence by providing her teenage daughter, Marozia, as a mistress for the Bishop’s recent predecessor, Sergius II. After Sergius’s death she married Marozia to a soldier of fortune, Alberic, marquis of Camerino, who was lionized after leading a decisive campaign against the Saracens, who had now advanced within forty miles of Rome, and were collecting tolls. With this danger removed, the Romans could now devote themselves to their customary intrigues.

Grown to formidable maturity, Marozia became known as the senatrix of Rome—not only the mistress and mother of popes (her illegitimate son by Pope Sergius II would reign as Sergius III)—but also the murderer of her mother Theodora’s lover, John X, who in 928 was seized and either starved or strangled in the dungeon of Castel Sant’Angelo (Hadrian’s tomb). Alberic disappears from the scene, perhaps to resume a life of crime, freeing Morazia to marry her lover Hugh of Provence—a potentially world historical match, considering the youth and pliability of her son the pope, who had it in his power to name them emperor and empress of the West. Inconveniently, Morazia had a younger son, Alberic’s namesake, but Hugh intended to blind him, following the custom that Italy had adopted from Byzantium of disabling a family member who stood in the way. Instead, Alberic the younger roused the Romans against the couple and, true to family form, arrested Morazia and consigned her to the castle’s dungeon for life. His half-brother, Sergius III, was relieved of temporal power, which Alberic exercised for twenty years as prince of Rome.

As he lay dying, the prince summoned Rome’s aristocrats to St. Peter’s tomb and made them swear a great oath that they would recognize his son Octavian, as his worldly heir, and, when the office became vacant, successor to the papacy as well. Having also inherited his father’s rivals and enemies—Berengar of Lombardy was closest at hand—the pope-king appealed to Otto, the Saxon prince who had mastered most of what had been Charlemagne’s empire, to become his protector, promising him what had been Charlemagne’s crown as a reward. Otto I was crowned at St. Peter’s on February 2, 961, marking the formal beginning of what became known as the Holy Roman Empire, of which Voltaire would say it was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire, and yet would endure for a thousand years. In May 996, his pious grandson Otto III, though fully expecting to be the last emperor, and eager to abdicate to Christ, dispensed with formality; and, when the papacy became vacant, he astonished Rome by simply appointing his cousin Bruno to reign as Gregory V in the short interval, as he expected, before the end of the world.

While the Latin West figuratively sat in darkness, Byzantium, the richest and most populous city in the world, and the Islamic capitals of Abbasid Baghdad and Moorish Cordoba in Spain(al-Andalus) literally blazed…

At the Millennium the dynastic feuds that consumed Italian prelates and German emperors were like back-alley escapades compared to the history unfolding in the vast dominions that otherwise encompassed their known world. “There are two empires,” wrote the Patriarch in Constantinople, “that of the Saracens, and the Romans (meaning the Greeks) who hold between them the entirety of power in this world, shining like twin torches in the celestial firmament.”

While the Latin West figuratively sat in darkness, Byzantium, the richest and most populous city in the world, and the Islamic capitals of Abbasid Baghdad and Moorish Cordoba in Spain(al-Andalus) literally blazed; the former preserving some of the glamor of the Arabian Nights, the latter (by modern standards) a cynosure of tolerance, sanitation, and night lighting. A presumably devout yet cosmopolitan intellectual elite kept these capitals and Cairo, Bukhara, and Samarkand in correspondence. Algebra, chemistry, Arabic numerals, and Aristotle were invented, refined, or preserved. Over the horizon, just out of Europe’s ken, was a Chinese empire vaster, more populous, more prosperous, and far more scientifically advanced. Yet, it was in the eleventh century that Europe became engaged in what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., blithely calls “the adventure of entering and altering nonwestern societies,” which would last almost another thousand years.

Sources:

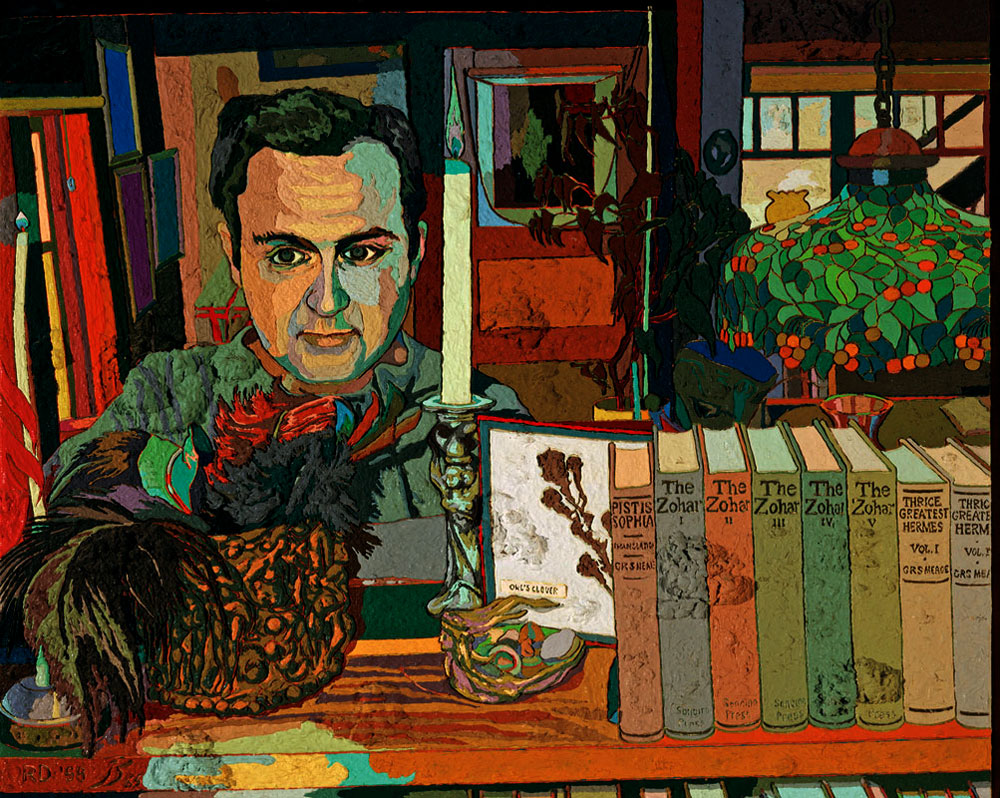

This essay is the second in a series. These are the books that were on my desk as I was writing this installment.

Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. J. B. Bury text, 1898.

Rodolfo Lanciani, The Destruction of Ancient Rome: A Sketch of the History of the Monuments. London, 1899.e

Henri Pirenne, Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade, trans. Frank D. Harvey. Princeton, 1925.

Steven Runciman, Byzantine Civilization. London, 1933.

Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs. London, 1951, fifth edition revised.

E.R. Chamberlin, The Bad Popes. New York, 1969.

Ferdinand Lot, The End of the Ancient World and the Beginnings of the Middle Ages, trans. Philip and Mariette Leon; 1931; rpt. New York, 1961.

Peter Brown, The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150-750. London, 1971.

Archibald R. Lewis, Nomads and Crusaders, A.D. 1000-1368. Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989.

John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries. New York, 1989.

Tom Holland, Millenium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christianity. London, 2008.

Michael Kulikowski, The Tragedy of Empire: From Constantine to the Destruction of Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA, 2019.