Byzantium’s Lonely Crowd

You will not find new places, you will not find other seas. The city will follow you. And you will grow old in the same streets, in the same neighborhoods; in these same houses your hair will grow white. It is always this city you will reach.

-C. P. Cavafy, “The City” (1911)

…And therefore I have sailed the seas and come /

To the holy city of Byzantium.

—W. B. Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium” (1927)

THE ROMANS OF CLASSICAL ANTIQUITY, from the age of Augustus to the reigns of Trajan, Hadrian, and the Antonines, abided in the Virgilian promise of an empire without end, but the Byzantines always knew they lived on borrowed time. A popular version of the Christian apocalypse told of a 1000-year Empire, of final days and a last emperor—a prophecy that, in the event, came true, but with a heart-catching fifth act.

Constantine the Great having inaugurated his New Rome on the site of ancient Byzantium, 11 May 330, it was not unexpected that the Empire would endure past AD 1000, a date which quickened doomsday expectations elsewhere in Christendom. At the millennium, Constantinople was the most opulent and populous city in the Western world, ruling a compact and defensible empire in Asia Minor, the Balkans, and the Aegean, having survived sieges, famine, plagues, and miscellaneous catastrophes since its foundation. In the mid-20th century the world-famous historian Arnold J. Toynbee addressed the mystery of how Byzantium survived when other medieval regimes did not by declaring the whole thing was an illusion. The Greek Empire, he argued, actually died in 602 when the decent but parsimonious Maurice was deposed by a brutish centurion, Phocas, best known for his ghoulish innovations.

“It was Phocas,” quoting John Julius Norwich, “who introduced the rack, the blindings and the mutilations which were to cast so sinister a shadow over the centuries to come.” Hitherto, the Empire had not been particularly cruel by the standards of the day; certainly not as gruesomely imaginative in this department as it now became. Toynbee, who started out as a Byzantinist, maintained that only a “ghost” of the Empire was revived by the low-born emperor Leo III (reigned 717-741), who routed Arab invaders by land and sea, only to throw Byzantium into confusion and turmoil with his iconoclasm. The gigantic revenant that he left behind stumbled along for another three centuries until the battle of Manzikert in 1071, after which Byzantium was an empire only by courtesy.

Back in the 1920s, H. G. Wells had explained the gigantic civilizational reversals of fortune in the 7th and 8th centuries that almost overwhelmed Byzantium in the racialist terms then in vogue:

A thousand years before, the Aryan-speaking races were triumphant over all the civilized world west of China. Now the Mongol had thrust as far as Hungary, nothing of Asia remained under Aryan rule except the Byzantine dominions in Asia Minor, and all Africa was lost and nearly all Spain. The great Hellenic world had shrunken to a few possessions around the nucleus of the trading city of Constantinople, and the memory of the Roman world was kept alive by the Latin of the Western Christian priests. In vivid contrast to this tale of retrogression, the Semitic tradition had risen again from subjugation and obscurity after a thousand years of darkness.

In the Decline and Fall, Gibbon pauses in the 7th century to give a gloomy preview of what is to follow:

From the time of Heraclius, the Byzantine theatre is contracted and darkened; the line of empire, which had been defined by the laws of Justinian and the arms of Belisarius, recedes on all sides from our view; the Roman name, the proper subject of our inquiries, is reduced to a narrow corner of Europe, to the lonely suburbs of Constantinople; and the fate of the Greek empire has been compared to that of the Rhine, which loses itself in the sands before its waters can mingle with the ocean.

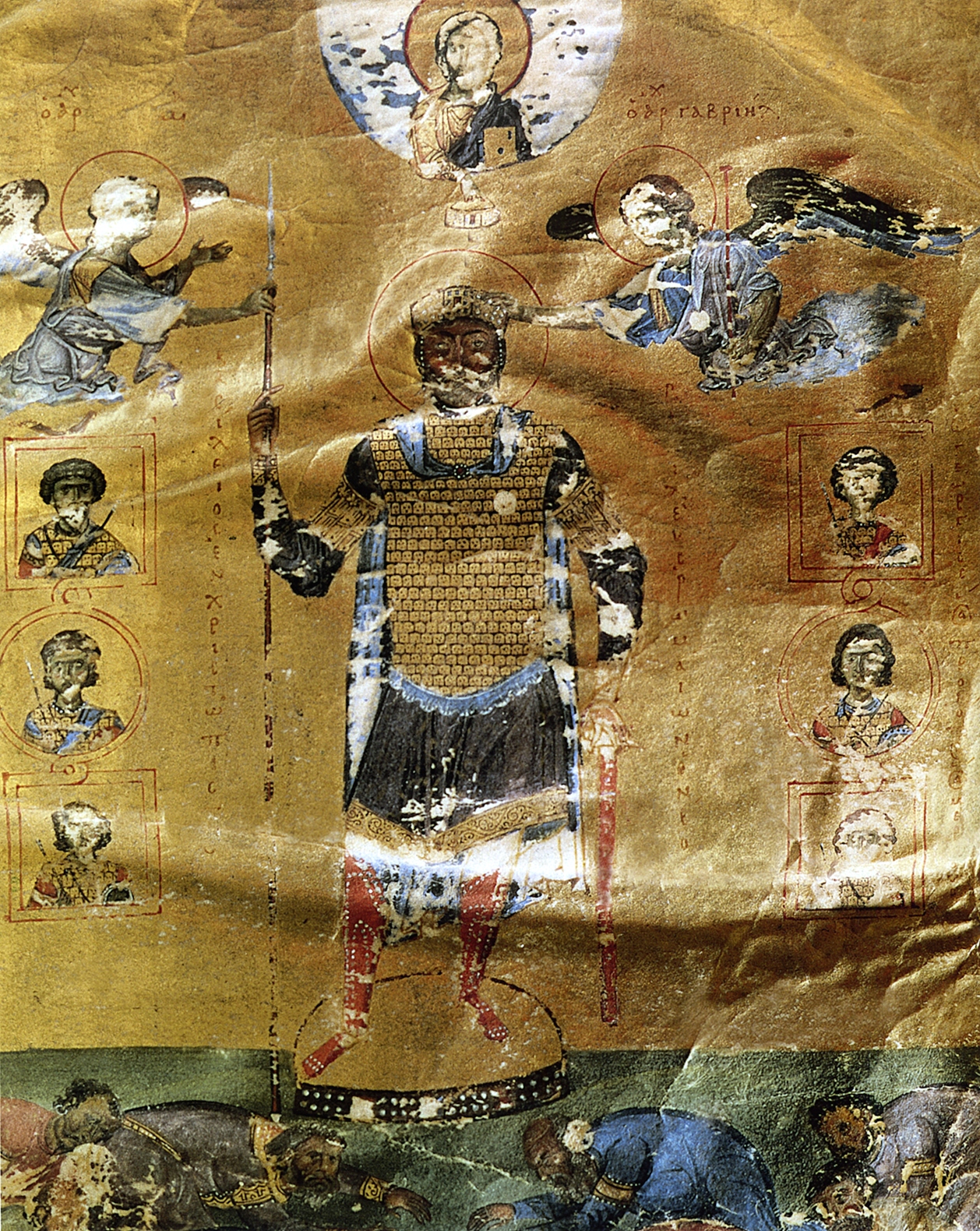

But riverine analogies are doubtful in human affairs, even—perhaps especially—when deployed by a genius like Gibbon. In flesh and blood the Empire endured, and in the fifty-year reign of Basil II (976-1025), it glittered again and grew. Born in the purple, Basil was a philistine compared to his forebears, his grandfather Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, the “Scholar-Emperor,” and great-grandfather Leo the Wise. Physically unimposing, uninterested in art or theology, and apparently indifferent to sex, Basil was a military genius who vastly enlarged on the triumphs in the Arab-Byzantine wars that had begun in his father’s reign with the recovery of Crete, after 136 years. Confronted with the latest hostile arrivals to the northeast, he became known to history as Bulgaroktonos, “the Bulgar-Slayer”—although his most famous dealing with the Bulgars was not slaying but blinding 15,000 captives and, sparing one in a hundred as guides, sending them home: legendarily, their king dropped dead at the sight. The Bulgar-Slayer was impatiently mounting an invasion of Arab-occupied Sicily when he died in 1025, unexpectedly leaving an empire at peace, as Romilly Jenkins writes in Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries (1966):

As far as the eye could reach, both west and east, the sky was serene and unclouded. Storms were gathering below the horizon, but who could foretell this? Far off in Transoxiana, east of the Aral, things might be unquiet, but the eastern frontier was splendidly fortified. In South Italy the Normans had shown their mettle, but they were no more than a handful, and as yet submissive to Byzantium. Mutterings could be heard from enslaved Bulgaria, but surely Basil had not spent fifty years for nothing in settling that problem? The conclusion seemed to be that no extraordinary efforts need be made to foster and strengthen the military arm.

Constantinople’s quarrelsome, riotous, and enterprising citizenry prospered behind huge, apparently impregnable walls. While preserving the arts and letters of antiquity for another day (it was the “Macedonian Renaissance”), the Empire remained the bulwark of the crude, ungrateful kingdoms of the Latin West. Even Gibbon concedes, “An historic light seems to beam from the darkness of the tenth century.” By comparison, “the cities of the West had decayed and fallen; nor could the ruins of Rome, or the mud walls, wooden hovels, and narrow precincts of Paris and London prepare the Latin stranger to contemplate the situation and extent of Constantinople, her stately palaces and churches, and the arts and luxury of an innumerable people.”

The arts of mosaic and painting glorified the church, while in Byzantium’s factories were manufactured the silks and brocades, the gold-, silver-, and enamelware which were for sale in a mile-long shopping district, partially lit at night. In literature Latin was a lost cause, but scholarship advanced the recovery of Greece’s classical past: Platonism (of a sort) was revived, and poetry from Homer on was collected in the immortal Greek Anthology. The most compendious account of the Empire’s provinces (themes) was assembled by that most studious autocrat, the emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus; its dynastic history was chronicled by the courtier, encyclopedist, sometimes eye-witness Michael Psellus in his Chronographia (usually translated as Fourteen Byzantine Rulers).

Always Gibbon comes back to his melancholy theme, the “Solitude of the Greeks.” The Byzantines considered the “barbarians,” such as the Slavs and Avars who harassed them in the North, to be scarcely human; the “more polished” Arabs spoke a difficult language and practiced an alien religion; their Christian brethren in the West were ill-mannered. The multitudes of Constantinople were a lonely crowd who had nothing to say to anybody else, and nothing they wanted to hear. “Alone in the universe, the self-satisfied pride of the Greeks was not disturbed by the comparison of foreign merit; and it is no wonder if they fainted in the race, since they had neither competitors to urge their speed nor judges to crown their victory.”

Yet, what a realm they inhabited, or believed they did! It was this millennial Greek Empire, not the rougher Empire of late antiquity, that was rediscovered and celebrated in 20th century art, literature, and historiography—a “rediscovery” epitomized in the gilded décor of W. B. Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium, ”the escape story of the poet from death into the “artifice of eternity”:

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enameling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

The multitudes of Constantinople were a lonely crowd who had nothing to say to anybody else, and nothing they wanted to hear.

FROM his drab work clothes to his indifference to art or heirs, Basil II was, as says John Julius Norwich, “deeply un-Byzantine”; he never married and died childless. Constantine VIII, his younger brother and successor, was deeply Byzantine in the prejudicial sense of self-indulgence and casual cruelty. On his death-bed Constantine was persuaded to decree the marriage of his daughter Zoe, a virgin of 50, to an elderly senator who—to abridge a long story—had a brief reign and suffered a suspicious death, immediately followed by the empress’s overnight marriage to a handsome youth who came from from Paphlagonia on the Black Sea. The teenaged brother of an influential court eunuch, Michael IV, as the boy became, ruled capably and campaigned bravely, until his early death from complications of epilepsy and dropsy. For thirty years or so, “the indefatigable Zoe,” as Gibbon calls her, ruled through husbands and favorites, some of them pressed on her by the court, others perhaps mere whims, while an over-ambitious patriarch successfully pursued a schism with the pope in Rome; by popular demand she was eventually joined on the throne by her detested younger sister, Theodora, a nun, who outlived her.

While Byzantium was indulging these dynastic dramas, the Seljuk Turks, prodded forward by more volatile Mongols, were advancing in Anatolia. In 1071, the emperor Romanus IV Diogenes met them in battle in Manzikert, was defeated and captured; he was ransomed under humiliating terms, but the Empire never recovered. In a day Anatolia was lost, and Byzantium ceased to be a great power.

IN the rational 18th century, Byzantium got a bad notice from Gibbon, hundreds of pages long, its conclusion: “In the revolution of ten centuries, not a single discovery was made to exalt the dignity or promote the happiness of mankind.” Nothing if not sweeping; and in the moralistic 19th century, W. E. H. Lecky delivered a yet more thunderous dismissal in his History of European Morals (1869):

Of the Byzantine Empire the universal verdict of history is that it constitutes with scarcely an exception, the most thoroughly base and despicable form that civilization has yet assumed… There has been no other enduring civilization so absolutely destitute of all the forms and elements of greatness, and none to which the epithet mean may so emphatically be applied. The Byzantine Empire was pre-eminently the age of treachery. Its vices were the vices of men who had ceased to be brave without learning to be virtuous… The history of the Empire is a monotonous story of the intrigues of priests, eunuchs and women, of poisonings, of conspiracies, of uniform ingratitude, of perpetual fratricides.

“The language is such a western Crusader of the twelfth century might have held, and often in fact did hold, about Byzantium,” the English Byzantinist Romilly Jenkins retorted a century later. “It is the outcome of the deplorable strife between Eastern and Western Christendom which begat in the West a long-standing hatred of Byzantium, still plainly discernible in the pages of the historians Gibbon and Voltaire, and of the novelists Walter Scott and George Eliot.”

Into the first half of the 20th century, a period which witnessed the geographical high noon of European empire and the nascence of the American, multicultural Byzantium—with its African, Macedonian, and Armenian emperors interspersed among the Greek, its simple qualifications for participation in its public life of speaking Greek and professing Orthodoxy, its magnificent devotional arts, its military and technological feats (“Greek fire”), and diplomatic dexterity—remained the great historical Other to the modern nationalist and ethnocentric West. Especially before the First World War, Byzantium’s blood-stained imperial cult, in which battles of succession routinely ended in the blinding and mutilation of the loser, and, no less, its sophisticated bureaucracy were alien to the ruling classes’ overall muscular Christian idea of themselves in Paris, London, and New York—the lowest blow struck by Theodore Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1912 was calling Woodrow Wilson a “Byzantine logothete.”

The scene changes after the Great War, which disillusioned its survivors and the younger generation alike. It was not coincidental that correcting the philistine Victorian prejudice against Byzantium became the cause of a cadre of brilliant young British philhellenes, most famously, Robert Byron, Steven Runciman, and Patrick Leigh Fermor. They were part of a privileged lot, mostly born in the reign of Edward VII, who (Byron and Runciman at least) would later comprise the gang of Bright Young Things chronicled and satirized by Evelyn Waugh in his early novels Decline and Fall and Vile Bodies and, later, romanticized in Brideshead Revisited. Their inheritance was Empire, which, as surely as Byzantium’s prophets had told their contemporaries, they were destined to lose.

Enabled by their “entitlement” in 20th century Britain’s much briefer imperium, the philhellenes advanced an historical enterprise going back to George Finlay, Lord Byron’s comrade in the Greek War of Independence.

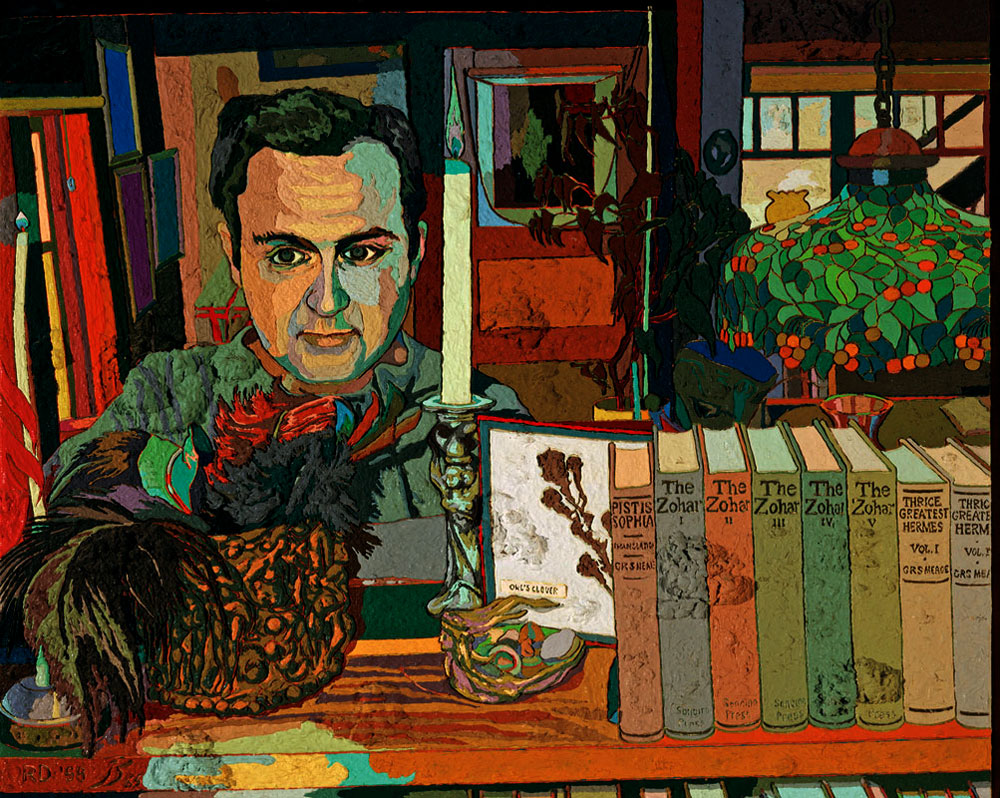

After graduating from Merton College, Oxford, Byron (no relation to the poet) made his first journey to Greece in 1925, driving across Europe to Athens with two friends, sustained by chicken in aspic and other provisions from Fortnum & Mason, a journey recorded in a novice book Europe in the Looking-Glass. His second voyage was a pilgrimage to the monasteries at Mount Athos which is told in The Station (1928), a small classic. The Byzantine Achievement followed in 1929, The Birth of Western Painting in 1930; the latter’s subtitle testifies to the range and ambition of Byron’s studies and travels by this point: “A History of Colour, Form, and Iconography, illustrated from the Paintings of MISTRA and MOUNT ATHOS, of Giotto and Duccio, and of EL GRECO.” Later travels took Byron to Russia, where he was revolted by Stalin’s police state, and Tibet; to Persia and Afghanistan, which gave him the materials for his masterpiece, The Road to Oxiana (1937), of which Paul Fussell says in Abroad (1980) that it is to travel writing between the wars what The Waste Land is to poetry and Ulysses to the novel. Heirs of empire: Byron’s companion on the road was Christopher Sykes, son of the diplomat Sir Mark Sykes, who negotiated the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement, which secretly divided the Middle East between Britain and France during the First World War. In spite of being a horrible snob, or likely because of it, Byron was one of the few English intellectuals who detested both Stalinism and Nazism without any period of gullibility or forbearance for either. A friend of the future novelist Nancy Mitford, he accompanied her sister Unity—who idolized Hitler—to the last Nuremberg rally in 1938. “These people are so grotesque,” he predicted, “if we go to war it will be like fighting an enormous zoo.” Byron died at thirty-five in 1941, when his troopship was torpedoed by the Germans off Cape Wrath in Scotland.

Steven Runciman, who published Byzantine Civilization in 1933, lived long enough to collect all manner of glittering prizes—honorary degrees, bestsellers, a knighthood, and streets named for him in Bulgaria and Greece—during a career industriously pursued until his death in 2000. Not for need. “Riches,” he said in late life, “should be the reward of hard work; preferably, of forebears.” An inheritance from his grandfather, a shipbuilding magnate, freed him to pursue a life of “private” scholarship; as a younger son, he was spared from the family business.

A studious child who read French at three, Latin at six, and ancient Greek at seven, Runciman grew into a gilded youth, who wrote to his parents in perfumed green ink, absent-mindedly earned a first in history at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was photographed by his friend Cecil Beaton with a parrot on a ringed finger. In later years he boasted of being “the first, and only, pupil” of the great J. B. Bury, whose writings, beginning with improvements and amplifications of Gibbon’s footnotes and culminating in a two-volume history of his own, helped rehabilitate the Empire in the eyes of modern scholars, now tenured in the once rough-hewn West. Although impressed by the undergraduate’s skills as a linguist, Bury warned him that “Byzantine studies were far too difficult for any innocent youth to undertake.” Undeterred, Runciman wrote a well-reviewed biography of the usurper emperor Romanus Lecapenus which won the attention of Bloomsbury, and, well reviewed, launched him on his long career. On his first trip to Greece in 1924 he was ravished by Monemvasia, the old commercial Byzantine stronghold on the Peloponnesus, counterpart to spectral Mystras, the subject of one of his last books, published almost 70 years later.

The almost equally long-lived Patrick Leigh Fermor is better known to the general reader, and led a more obviously adventurous life. In December, 1933, aged 18, he set out from Holland to Constantinople (not Istanbul, he specified), traveling on foot, sometimes horseback, at a leisurely pace, enjoying the adventures and gathering the impressions that would take him 40 years to put into print. (“Laziness and timidity,” he explained when pressed to explain the long delay.) As a commando during the Second World War, Leigh Fermor parachuted into Crete, where he spent two and a half years on a mountain-top disguised as a shepherd and, with the local resistance, helped organize the kidnapping of a German general. Like Runciman, Leigh Fermor found his way to Byzantium through the Peloponnesus, where the Empire breathed its last enchantments. After the war, he and his wife Joan designed a house at the remote southern tip of the Peloponnesus, which became a literary destination for literary travelers like the great James Campbell and the setting of his classic book about the region, Mani (1958).

Enabled by their “entitlement” in 20th century Britain’s much briefer imperium, the philhellenes advanced an historical enterprise going back to George Finlay, Lord Byron’s comrade in the Greek War of Independence. Long outliving his world-historical friend, Finlay, staying on in Athens, wrote a multi-volume history of Greece between 1843 and 1861 including two books on Byzantium; lightly regarded in his time, they have been respectfully resurrected. The Yugoslav scholar George Ostrogorsky’s classic History of the Byzantine State (1940), addressed to scholars, appeared in English in the mid-1950s, while the English captivated a larger audience with their bright chronicles. By the time Romilly Jenkins was writing the Imperial Centuries in 1966—in the splendor of the Harvard research institute at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., a world center of Byzantine studies—the Empire had gained a new allure and renewed pertinence.

In 1965, reviewing Sir Steven’s The Fall of Constantinople, 1453, Gore Vidal observed:

During the last forty years the attitude of the West toward Byzantium (best expressed by Gibbon) has changed from indifferent contempt to a fascinated admiration for that complex and resourceful society which endured for a thousand years, governed by Roman Emperors in direct political descent from Constantine the Great at the juncture of Europe and Asia into the New Rome. When the Western Empire broke up in the fifth century, Constantinople alone maintained the reality and mystique of the Caesars.

In 1961 Vidal was at peace with the Kennedys (except for Bobby), having shared a stepfather with Jacqueline Bouvier and supported Jack’s presidential race. In a dispatch to a London newspaper about the new Augustus of the West, he provided a curious detail: “Over the years I’ve occasionally passed books on to him, which I thought would interest him (including such arcana as Byzantine economy).” Really? But if the Cold War was turning out to be “a long twilight struggle,” as JFK later and famously said, surely there might be lessons from the Empire in its 1000-year struggle, which continued even as the Greeks grew ever lonelier and their lives more shadowy.

At midnight on the Emperor’s pavement flit

Flames that no faggot feeds, nor steel has lit

No storm disturbs, flame begotten of flame,

Where blood-begotten spirits come

And all complexities of fury leave,

Dying into a dance,

An agony of trance,

An agony of flame that cannot singe a sleeve.

Isolation was no longer splendid. The darkness surrounded them.

Sources:

John Julius Norwich published Byzantium in three volumes from 1988 to 1995; the masterful abridgement listed below is recommended to the reader who might hesitate to spend the time required to read 1200 pages in what Lord Norwich calls “the strange, savage, yet endlessly fascinating world of Byzantium,” without a preliminary reconnoiter.

Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. J. B. Bury text, 1898.

Rene Guerdan, Byzantium: Its Triumphs and Tragedy, trans. D.L.B. Hartley, preface by Charles Diehl. 1957, rpt. New York, 1962.

William Holden Hutton, Constantinople: The Story of the Old Capital of the Empire. London, 1900.

Romilly Jenkins, Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries A,D. 610-1071. New York, 1966.

Herbert J. Muller, The Uses of the Past: Profiles of Former Societies. New York, 1952.

John Julius Norwich, A Short History of Byzantium. New York, 1997.

Steven Runciman, Byzantine Civilization. London, 1933.

H. G. Wells, A Short History of the World. 1922; rpt., edited with notes by Michael Sherborne, with an introduction

by Norman Stone, London, 2006.

Gore Vidal, “President Kennedy,” London Sunday Telegraph, April 9, 1961; “Byzantium’s Fall,” The Reporter, October 7, 1965. Both are reprinted in United States: Essays 1951-1992. New York, 1993.