"The big joke on democracy is that it gives its mortal enemies the tools to its own destruction." —Josef Goebbels

"This ain’t really a life, ain’t really a life, ain’t really ain’t nothin’ but a movie…" —Gil Scott-Heron

In the days before the election of 2024, I took a bus from New York to Philadelphia, to doorknock for Kamala Harris in a swing state. The Harris campaign was organized, disciplined, and focused, dispatching volunteers from all around the country and beyond—the authoritarian threat that Donald Trump represents has focused minds across all borders—to neighborhoods all over the city.

In training, we were given a cringe-inducing script to read on canvassed doorsteps (“I’m talking to folks in your neighborhood about Vice President Kamala Harris because she’s just like us…”). We were told we could discard this script, and we did.

Over several days, I worked shabby but comfortable middle class areas, suburban streets of imposing brick houses, gentrifying neighborhoods of young professionals, and slum areas in which decaying row houses stood among the garbage and broken furniture on their porches. Houses in all of these neighborhoods had internet doorbells. The campaign had already blanketed the city. Some of these citizens were being knocked for the fifth time.

Although the polls were reporting a close race, it seemed inconceivable that Harris could lose: that the only president in American history to have attempted to stay in power after losing an election, an obviously personality-disordered sociopath bent on revenge against the democratic institutions he had not been able to defeat four years ago, a thug and an enemy of the rule of law, could be returned to office. Surely Americans have more respect for our history and political values – indeed more respect for ourselves as citizens and human beings – than to allow this? Indeed, the volunteers were uniformly fired up: “She’s going to win, there’s no doubt.” A canvassing captain told me that women would put Harris over the top. “The number one Google search this week was, ‘Will my husband know how I voted?’”

This was sociologically disturbing but electorally encouraging: are the polls missing these armies of women voters, afraid to be overheard expressing their support for Harris? I was skeptical. My own Google search of Google searches did not confirm this anecdote. We wanted to believe it.

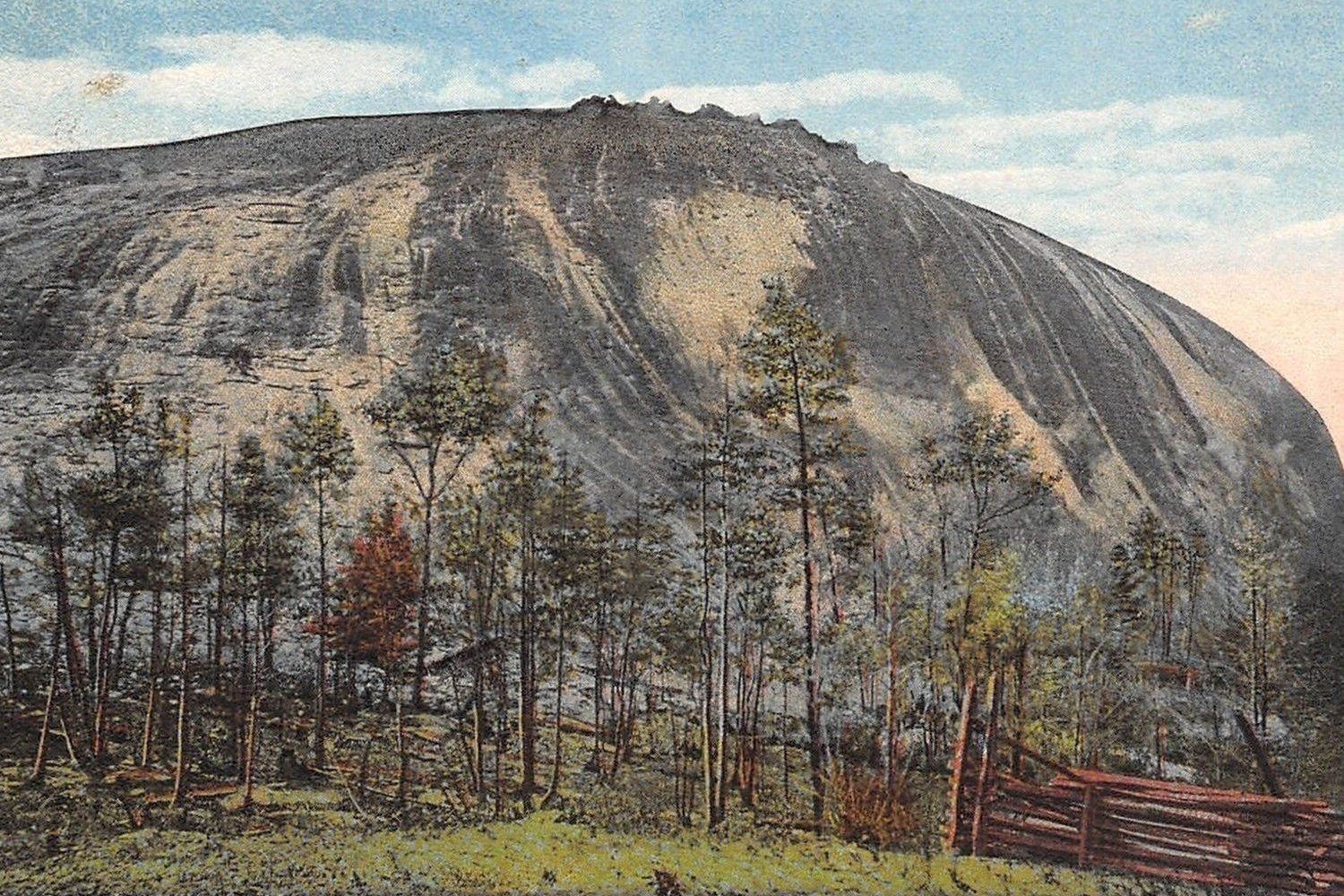

And yet, one quiet bright autumn morning, the sun shining down through the trees on a street planted with Harris signs, wind swirling the fallen leaves on the lawns, a sense of doom found me. A Trump restoration seemed all too plausible, with all of its implications: the end of the Republic, of the rights of citizens, of a stable world order, fed to the fires of a mass hallucination.

We’ve always had strange men among us, men who believe that it is their destiny to rule the world. Most of us avoid these people, as they go about an isolated existence, mumbling to themselves of enemies and conspiracies that only they can vanquish. Sometimes their lives will erupt into acts of savage violence, directed against themselves or others. Much more rarely, such a man—a failed artist, say, or a failed seminarian, or a failed real estate developer—will find himself on a stage, with thousands of people screaming his name.

Following the November 5th vote, there are any number of explanations for the normal candidate’s loss. Inflation, racism, Ukraine, misogyny, Gaza. The need of the rural working class to be “seen,” the cultural sidelining of men. Trans women in women’s spaces. It all seems as surreal as it does irrelevant. The American public voted to reinstate the one president in the nation’s history who refused to leave office after losing an election; who has displayed nothing but contempt for law, custom, and propriety. He won all of the swing states. And a plurality of the popular vote, constitutionally irrelevant but of great importance to the perception of legitimacy. It is a tremendous humiliation for a nation that aspires to be a nation of laws.

Donald Trump, in office or on the campaign trail, is not like any other American president. It is not the incompetence that sets him apart, the proud know-nothing refusal to engage the facts of the world; we’ve had presidents like that before, notably a string of failures prior to the Civil War. We’ve had corrupt presidents, dishonest ones, vicious ones.

What makes Trump unique as a political leader is his malignant narcissism, the vortex of his psychological need that makes him the sole reference point of political administration. Other presidents lied out of political expediency, out of fear, to protect allies or henchmen, to avoid responsibility. Other presidents were corrupt as an opportunistic sideline, or out of nepotistic indulgence. Other presidents broke the law because they found it in the way of their policy goals.

For Trump, the corruption, the lies, the lawbreaking are the policy. They are central to the existential meaning of his leadership, which is to exalt his infallibility. They are his claim to control reality itself, much as a Sharpie pen, in his magical hand, could control the course of a hurricane. His personality is inimical to the institutions that have evolved to protect American democracy, not merely the formal constitutional protections of rights, but more importantly the informal conventions and protocols that democracy absolutely depends on: a politically insulated Civil Service, a mechanism for investigating wrongdoing in the executive branch that sidelines officers serving the executive, judicial review of presidential actions. Respect, forbearance, and an assumption of good faith between political parties. A military scrupulously separated from politics. The tradition of a gracious concession following an election loss. Cooperation and collegiality between an incoming and outgoing president, even when they are rivals from different parties; and political silence from ex-presidents.

Trump has undermined and attacked every one of these conventions, and in a second term he will attempt to destroy them. It’s not that he rejects the premise behind them; it’s not even that he doesn’t understand that premise. It’s that his disordered personality makes it impossible for him to understand it. The rituals and performances of public life exist to feed his narcissism. He insists on massive military parades, in defiance of American military tradition, because he imagines they proclaim his personal strength; and banishes disabled veterans from the event, because their visibility “doesn’t look good for me.” His only criterion for analyzing the bizarre QAnon conspiracy theory is that “they like me very much.” Trump in office did not have policies, and did not understand nor respect the policy-making process. He had narcissistic whims; usually whims that played on his deep need to appear to be “strong,” as a weak man conceives of strength.

In international relations, “I like people who like me.” Trade policies, geostrategic imperatives, human rights positions, political freedoms—all of these are less important than a leader who “says nice things about me.” To Trump, foreign policy springs from personal relationships among leaders and depends on other leaders’ praise for him – an orientation that opens obvious opportunities for gains by authoritarian states at American expense, on the trivial cost of a bit of flattery.

A generation ago, it would have been impossible for such an obviously damaged person to be taken seriously as a presidential candidate. Over the last 30 years, we have increasingly lived in a social media environment that has invited us to create, share, and voyeuristically consume a common digital life. It is not so much that Trump’s narcissistic approach to the presidency has been normalized, although it has; it is that solipsistic self-reference has eaten the larger culture, in an omnipresent twilight of “influencers,” cultural activists, conspiracists, and fame junkies fed by radicalizing algorithms seeking eyeballs for the next sponsored video. Our politics has less and less connection to any actual reality. We put ourselves on display 24/7, and the confessional style in public life is as normal as loud cell phone conversations on public buses. We are all narcissists now, and the destructive narcissism of the leader reflects and magnifies the aspirational narcissism of his devoted followers. Like all systems built on spectacle and cruelty, the unraveling of democracy has a performative aspect that feeds popular enthusiasm for the most flamboyant strongman.

Such a moment has produced a leader who came to public attention as the host of a reality show in which he was portrayed as a masterful businessman, sharp, decisive, and competent. None of this was true; Trump made terrible business decisions in real life, got into unmanageable debt, and declared bankruptcy six times, leaving his hapless investors, employees, and contractors holding the bag. But the show created its own narrative, and played to the audience’s most base and bullying instincts—and would have pushed things further, had its star been allowed to. Trump wanted to pit a team of black contestants against a team of white ones. This impulse predicts much about the nature of Trump’s campaigns—and of his behavior in office.

A radical, destabilizing oligarchy at the head of a pixel-drunk mob has seen the opportunity in a world in which the idea of respectable public media is no longer associated with fact-checkers and gatekeepers, Artificial Intelligence is being deployed against democracy, and the far right has been hammering on conventions of pluralism, truthfulness, and respectful disagreement since the days of Newt Gingrich in the mid-1990s. Its program of tribalizing and demonizing politics, while deploying an alliance with both informal and corporate post-truth media, has not only turned politics into a blood sport. It has turned politics into entertainment. It is telling that not only does the truth now not matter to many; it is admitted and acknowledged not to matter. The point is the tribal performance of a political identity.

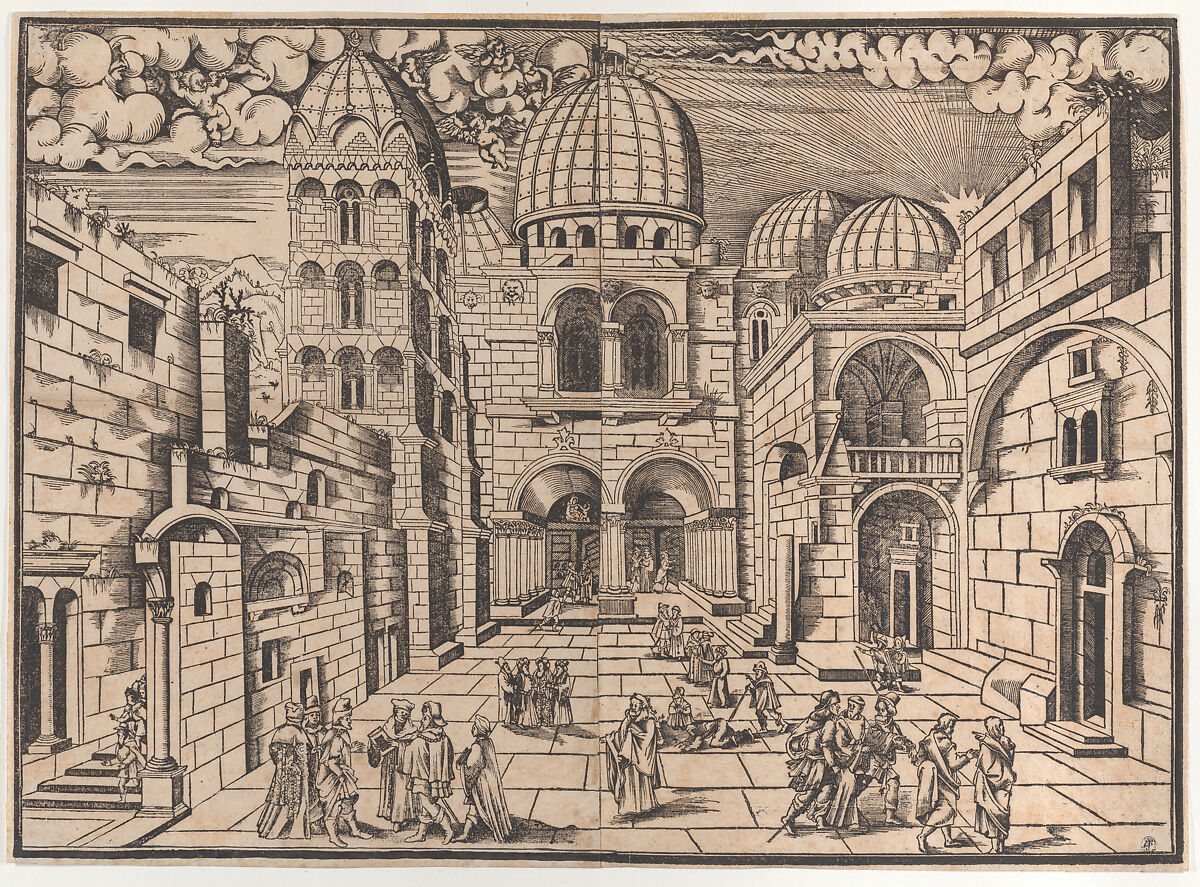

I can think of democracies that were crushed by authoritarian neighbors. I can think of egalitarian societies that succumbed to an oligarchic elite, and of reforming monarchies that were swept away by totalitarian revolutions. I can think of societies that offered some broad degree of political autonomy to their citizens and institutions that were hijacked by ambitious dictators who consolidated power. What I cannot think of in history before now is an established, longtime democracy, with strong democratic institutions and an historic if imperfect dedication to the rule of law, in which a broadly enfranchised electorate voluntarily voted to enthrone a person who aspires to be a dictator.

If Trump has his way, the vast administrative apparatus of policy-making, of institutional review, of rules and regulations and laws—the necessary insulation of power in a democracy—will be jettisoned in his war on the “deep state”—which is to say, the process-based foundations of democracy that diffuse and check power. Whereas in his first term Trump believed only in ignorance that the American president held unfettered power, he now knows what he needs to do to actually achieve it.

The system is much more fragile than we had assumed. There were multiple opportunities for a healthy democracy to assert itself against Trump’s narcissism. The Republican Party could have taken seriously the traditional role of political parties as gatekeepers, blocking Trump from the nomination in 2016 and 2024. The Senate could have acted honorably and convicted Trump when he was impeached in 2019 and especially in 2021, when the magnitude of his assault on the Constitution was beyond any doubt. The justice system could have moved much more quickly to charge and convict him on election fraud and insurrection charges. The states could have refused him access to their ballots as an insurrectionist. And, of course, the people could have valued democracy enough to vote against him.

None of these things happened. Instead, the Supreme Court held Trump above the law.

Where might we as a nation go in the course of a second, much less restrained Trump presidency? The political culture is moving very fast, in all kinds of ways. One of the reasons that a trial of Trump’s serious crimes—who cares about hush money paid to a porn star?—was so important for the nation was that a demonstrated duty to impartial justice would have served to shore up our institutions. That’s not going to happen now. Instead, our public servants who have demonstrated the highest degree of integrity in attempting to prosecute Trump may well be targeted by the corrupted power of the presidency. We are now fully exposed to the coming hurricane of venality, incompetence, corruption, and authoritarianism, and we should be prepared.

Americans have been smug about our leadership of the free world since 1945, and after 1989 we got used to thinking of liberal democracy as the inexorable trend of history. But there was nothing in its very brief timescale that warranted such a projection. Maybe it was just the most temporary of blips, presaging nothing more than a quick reversion to normal autocracy.

I’ve always known that there will come a day when the United States is no longer a democracy, and a day when it no longer exists. But until recently, I never thought these things could happen in my own lifetime.