“Madero has unleashed a tiger; let us see if he can control it.”

-Dictator Porfirio Díaz on Francisco Madero’s setting off the 1910 Mexican Revolution

In his compendious The City in History of 1961, Lewis Mumford singled out the importance and uniqueness of the “University City,” and in his supportive photograph flashed on the city of Berkeley with its University of California to drive home his point: “The most essential role of the city …—that of enlarging and transmitting the cultural heritage—is now being performed chiefly in university cities, of the order of Berkeley.” The University holds a key position: “For the school sprang from the Greek polis’ margin of leisure, and in the opening age, paideia, or education in the fullest sense, … will become the essential business of life.”

A mere three years later University of California President Clark Kerr followed up on Berkeley with his Harvard lecture on The Uses of the University, in which he highlighted the university as the modern equivalent in its multifarious functions to the classic city, just as the college campus town had been to the town. This city should be henceforth titled Ideopolis and would brew vast new cultural, artistic and intellectual progeny that the university alone was capable of supplying to modern life through its role as a Multiversity.

Almost immediately, unresponsive critics—many being university undergraduates who had engaged in civil rights action in the American South—lashed out against this student-unfriendly vision of the university to set off the Free Speech Movement (FSM) of 1964. From that moment on “Berkeley” became permanently associated with the accusatory cognomen—and celebration—of “Radical.” Over thirty-odd years later and despite fundamental changes at the university itself as well the surrounding city of Berkeley, such “radicalism” has remained so strongly associated with Berkeley that fictional Mafia boss Tony Soprano could but harshly forbid (as only Mafioso dons can do) daughter Meadow from ever contemplating attending such a cesspool of radicalism.

As ever, Tony was prescient in his raw sense for reality. After all “Berkeley” had been invented by Californians for a civic site that remains the only world-historical example of a full-sized city or urban space named after an eponymous hero culled from the annals of formal Philosophy (there has never been a Greek Platoville, French Descartesburg, or even Chinese Confuciusopolis). The philosopher whom the city fathers meant to celebrate was the scandalous George Berkeley, and his eighteenth-century message was “Immaterialism”: strictly speaking, ladies and gentlemen, Matter does not exist, reality consists either of Perceiving or Being Perceived, in short, it is through and through “Spiritual.” It is an outlook that, however coincidentally, is mirrored by hosts of Berkeley “crazies” (“Berserkeley”) who have shaken the contours of the ordinary or conventional reality enjoyed by the rest of us mortals dwelling in this city that squarely faces the Golden Gate and opens out into the largest ocean of the known universe, this “Athens of the Pacific” destined to adjudicate, however clumsily and self-righteously, all critical ideological currents between East and West.

The Berkeley protest example went on to unhinge a host of other campuses and urban centers across the globe. There were a number of commendable practical results—elimination of the traditional university in loco parentis being a common and overdue benefit. What is however difficult to grasp from the outside is the Experience itself, about which the participants found themselves—as in the case of True Love—generally inarticulate (Berkeleyan Michael Rossman coming closest in his efforts to formulate the Ineffable). It is something that participants to the joli Mai of Paris 1968 or, for that matter, the Velvet Revolution of 1989 Prague similarly flunked at.

Almost immediately, unresponsive critics…lashed out against this student-unfriendly vision of the university to set off the Free Speech Movement (FSM) of 1964. From that moment on “Berkeley” became permanently associated with the accusatory cognomen—and celebration—of “Radical.”

Philosopher Martin Heidegger once defined the polis itself as “the site, the Da in which and as which Da-sein as historical is, the history-site… from which History Happens.” If Da is to be translated as “openness” (as Heidegger had the right to insist from his English readers), then we have a meaningless—but not pointless—definition urging us to contemplate the openness that necessarily belongs to the authentically historical. Whatever the cavils about Berkeley between the FSM in 1964 and the People’s Park demonstrations of 1969 (which incidentally came up with the first use of “green” through Girl Scout uniform flags for forthcoming expressions of environmentalism), something “extra”-ordinary had clearly transpired along its lanes and avenues.

No big surprise then that the psychedelic, or more properly “psychonautic,” revolution also burst out of Berkeley during this very period. There, in Thomas Pynchon’s one great novel The Crying of Lot 49, goes Oedipa Maas crossing the Berkeley campus circa 1965 to negotiate that tremblingly taut line between campus revolutionaries and a burgeoning LSD-soaked intuition. It seems a far cry from Emerson Elementary and Berkeley High graduate Thornton Wilder’s concoction of his prototypal Our Town in 1938, ostensibly located in New Hampshire but really all about the quiet streets and pathways of a remembered Berkeley. Yet both after all share ruminations on death and ghosts of sorts—that Other universe which psychonauts above all ache to access. To help the cause Berkeley even put up a factory (across from the present Totland children’s park) to churn out Owsley Stanley’s fabled LSD pills (“Owsleys”), and over the course of a half-century Berkeley native Alexander Shulgin ran a dizzying set of psychedelic doses in his magical lab, highlighted by his synthesis of MDMA into the therapeutic and rave-club superstar Ecstasy.

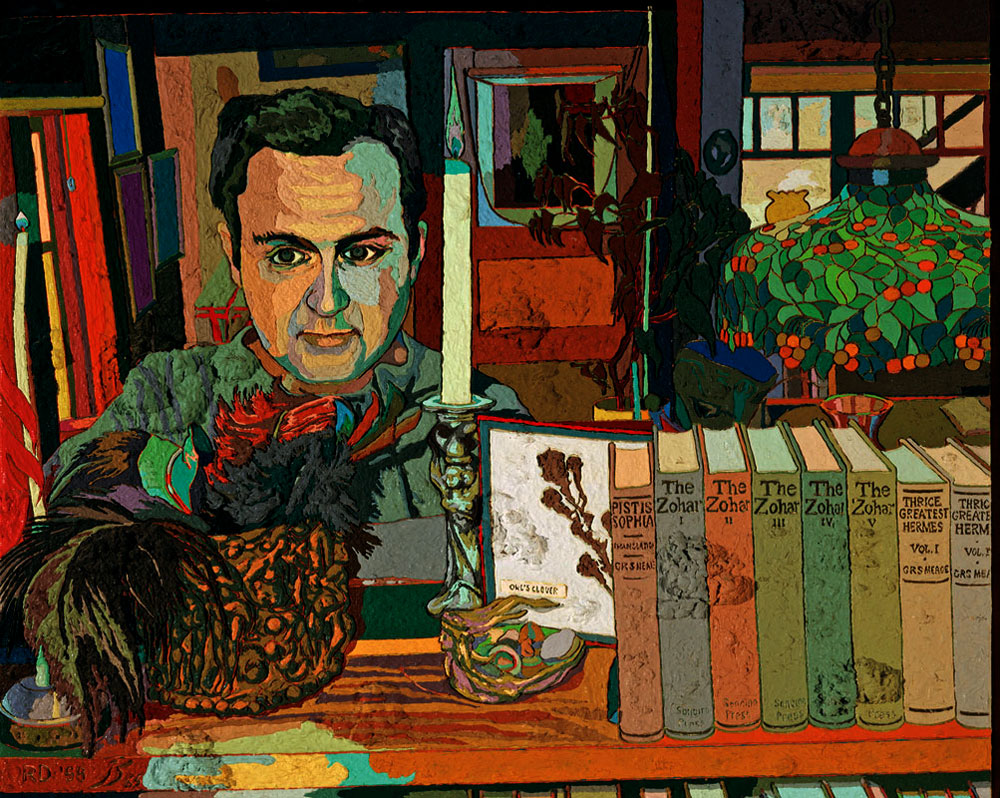

In the course of which young Terence McKenna arrives on the FSM campus in 1965 and shortly thereafter first smokes the super-powerful psychedelic DMT in 1966, perched, as Erik Davis glosses in his informative High Weirdness, to take on “the radical subversion of reality itself.” Later in 1985 McKenna in Berkeley meets José Argüelles, at that time a San Francisco State professor in art and cultural history before graduating to the future Mayanist prophet Valum Votam, where they concoct the grand idea of an epochal cosmic transformation in 2012, presumably according to the Mayan calendar (and perhaps the I Ching). Of course they were right: the Singularity, first announced by L.A. novelist Franz Werfel in his 1945 masterpiece Star of the Unborn and later cribbed by a host of futurological louts, has indeed always been taking place (have a glance about you when embarked on a psychonautic voyage); but from an “autochthonous” Berkeleyan perspective, so what?

Of course more “serious” events presaging the total destruction of the Earth have chosen Berkeley for their toxic cradle. Thanks to physicist Robert Oppenheimer, Berkeley was key to the creation and detonation of the atom bomb through the Manhattan Project that Oppenheimer not only directed but also specifically sited on Los Alamos, over—you guessed it—Native American ancestral lands. Oppenheimer may have repented his involvement in time, but his colleague Edward Teller, pushing on to the fatal splendors of the hydrogen bomb, would later await word of the fatal experiment in the basement of the University of California geology building: “the sound waves took twenty minutes to carry the message under the Pacific and arrive in Berkeley.” After all it had been on the Berkeley campus that while the chimes rang out “like the music of the spheres” for the first time the conversation of these technoscience giants had turned to the “idea of man-made suns.”

Preferring to sound the story of Berkeley in a more benign key, the Beat Movement, now an irremovable cultural kidney stone in intellectual history, experienced perhaps its gentlest moments in the floral vales of Berkeley backstreets. A cottage on 1624 Milvia Street once nestled Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, and Jack Kerouac to ponder Buddhist profundities and Tantric erections. Kerouac’s reminiscent The Dharma Bums captures a mood which, however fictionalized, does retain some of that “flowery” flavor, as Kerouac biographer Anne Charters has described Berkeley (in his most famous treatise even Mexican author Octavio Paz had to acknowledge “la bellezza de Berkeley”). Temporarily envisaging Berkeley as a possible home for himself and his mother, and even renting an apartment on 1943 Berkeley Way, Kerouac ran one day into Neal Cassady to pass on to its hero a first copy of On the Road, thus perfecting the Best Buddy storyline. Alas, only a storyline, given both Cassady’s and Kerouac’s later rapid descents into meaningless deaths.

More positively instructive are the narratives of science-fiction masters Ursula Le Guin and Philip K. Dick—at least for a while. Both 1947 graduates from the same Berkeley High class without knowing of each other, Le Guin and Dick went on to reframe the interrelated genres of science fiction, fantasy, and space opera, Le Guin carrying through an imposing oeuvre of fictional and philosophical writings right to her death, while Dick eventually devolved into a long paranoid fix (in the Orange County of his day no less) punctuated by images of reborn Roman villains and Christian fugitives, of which he was presumably one. Still, the years 1968-1969 witnessed some of their best productions in charting worlds bearing the broadest of speculative possibilities, not excluding Le Guin’s razor-sharp glimpses into emerging gender, ethnic and racial futures.

[Charles] Keeler’s “Simple-Home” philosophy, conceived in friendship with organic architect Bernard Maybeck…set forth the characteristic Berkeley aspiration to domestic comfort, functionality, environmentality, and a strong dose of Spirituality.

Appropriately for some such utopian/dystopian spirits the “New Age” proper naturally found eager adherents among a generation or more of Berkeley Seekers. Besides the occasional presence of such New Age publishers as Shambhala Press, which brought out Tantric Buddhist texts at a time of the Dalai Lama’s visits to the Buddhist Nyingma Center, a bevy of presumably enlightened visitors—from EST guru Werner Erhard, who had been turned on to Martin Heidegger’s philosophy by Berkeley professor Hubert Dreyfus to Rajneesh and his orange-garbed acolytes floating down from Rajneeshpuram in Oregon to the money mammaries of the Bay Area—kept aflame the long-standing Berkeley flirtation with Convenience, both spiritual and material, going back perhaps all the way to Charles Keeler and his Hillside circle in North Berkeley. Keeler’s “Simple-Home” philosophy, conceived in friendship with organic architect Bernard Maybeck—whose student Julia Morgan flocked the hills and city of Berkeley with many a sturdy example of redwood craftsman—set forth the characteristic Berkeley aspiration to domestic comfort, functionality, environmentality, and a strong dose of Spirituality. Not to ignore cuisine and drink either: Berkeley’s “gourmet ghetto” came to star Alice Waters’ forays into a distinctive California cuisine at her celebrated Chez Panisse restaurant, while around the block, in conjunction with Berkeley’s introduction of coffeehouses and expressos to the United States Alfred Peet launched the first Peet’s coffee shop at Vine and Walnut. Supporting such Berkeleyan flavorings there is even a distinctive Berkeley signage around town cultivated by designer David Lance Goines that one might provisionally dub “Berkeley artisan craft.”

A world center for academic publishing, Berkeley prodded one UC Press editor Ernest Callenbach to etch out in his self-published Ecotopia a first exercise in ecological sustainability. The environmentalist constrictions his utopia imposed were meant for Berkeley’s primarily white residents, but Callenbach graciously allowed its Black constituents a longer period in conspicuous consumption as a concession to cultural catch-up. To be sure, Callenbach’s Berkeley has been touted as the Californian “Capital of the Upper Left,” bastion of a resolute progressivism which, while not risking the kind of sophisticated Marxism of Critical Theory that the last of the Frankfurt School, Leo Löwenthal and his long-standing Berkeley reading group, encapsulated, has remained sufficiently “left” to merit its notoriety as the most liberal city on the planet (incidentally rejecting Donald Trump by 95-3% in 2016 and 93-4% in 2020). Thanks to its reputation and incidental amenities Berkeley has long offered facilities and support for people of disabilities with its Center for Independent Living, and it has ranked as a preferred locale for widely diverse gender lifestyles.

Back in 1954 however, my neighbor Gene Tarrant sought far and wide for a home for him and his wife Mary in the Berkeley hills; without success, notwithstanding friendly smiles of avoidance. Eventually he settled for a home on 2327 Edwards Street in Berkeley’s flatlands in a section called “Poet’s Corner.” The morning after he and Mary moved in, a hostile mob with quiet menace waited for them outside on his lawn. Having risked a full Pacific stint as Pearl Harbor survivor and warrior, Gene simply dismissed them out of hand; they never showed up again. Gene went on to start the first Berkeley neighborhood committee, for which Edwards Street has been more lately named after him and Mary.

Gene’s home lies some three blocks from the apartment where U.S. vice-president (and possible future first woman president) Kamala Harris grew up. She recalls the area as “a close-knit neighborhood of working families” where “people believed in the most basic tenet of the American Dream.”

Now which one is that?

Berkeley continues to beguile. Berkeley continues to frustrate, cozily transgressive, unrepentantly open-minded: the Polis where, as Heidegger once framed it with his coyly alliterative German: “History Happens” (die Geschichte geschieht).