I am learning to live in history.

What is history? What you cannot touch.

—Robert Lowell, “Mexico” (1967-68)

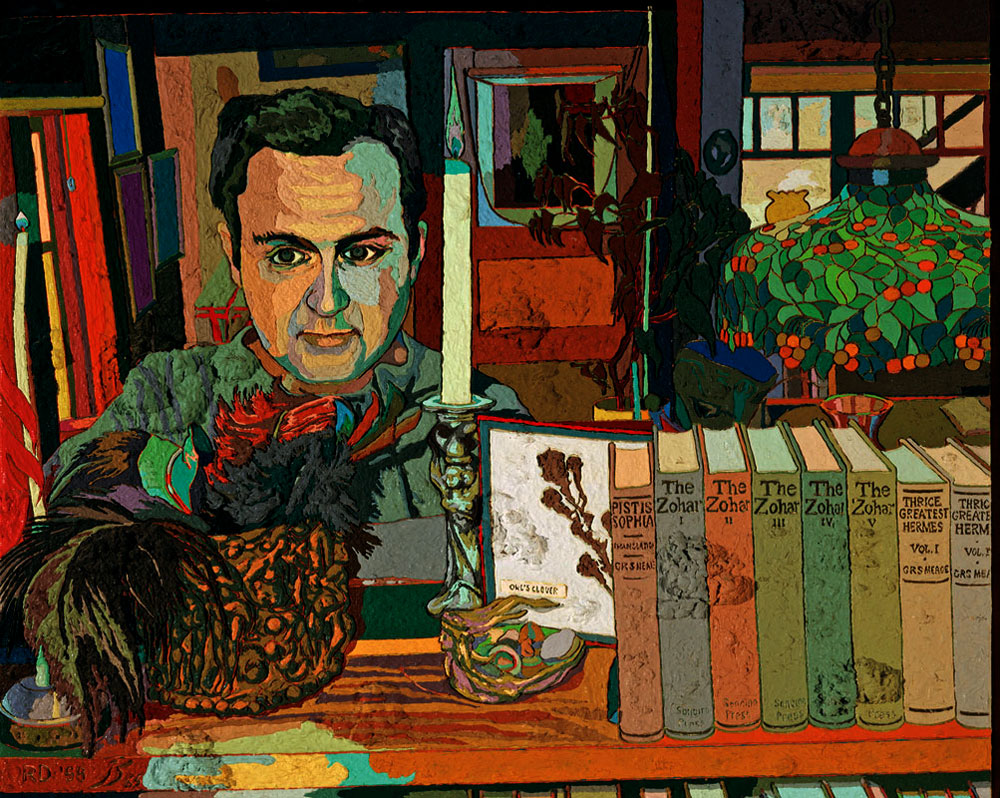

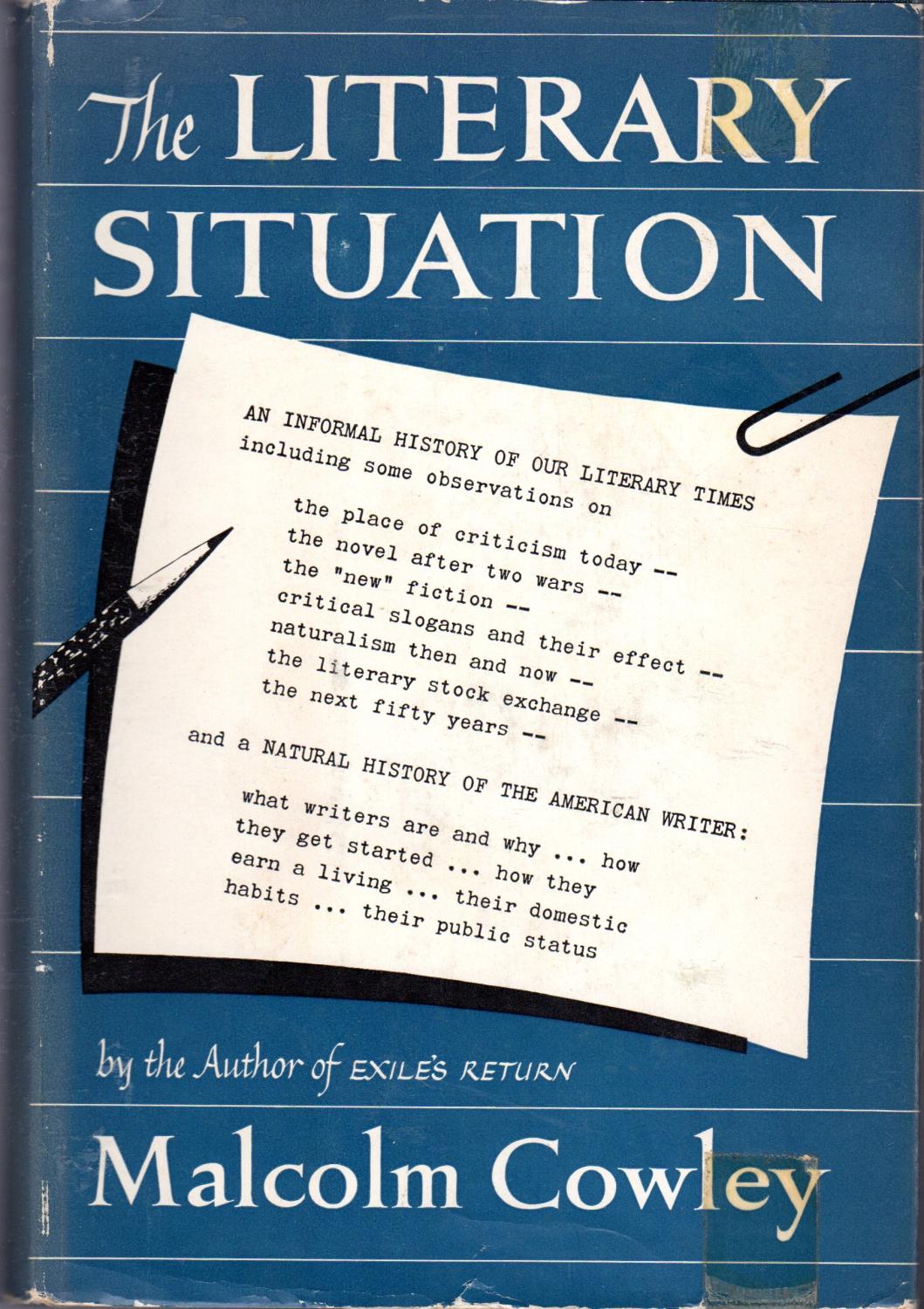

IN JULY 1954, THE NINTH SUMMER AFTER THE WAR, Malcolm Cowley was winding up The Literary Situation, his appraisal of life and letters in the U.S. at the mid-century, with a look to the future. The chapter was titled “The Next Fifty Years in American Literature.”

A poet in his youth, Cowley dropped out of Harvard during the Great War to volunteer as an ambulance driver for the French army. In the 1920s, he joined the pilgrimage of his Greenwich Village cadre to Paris, where, fellow voyager of Hart Crane, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Dos Passos, he edited little magazines and consorted with Dadaists. With the publication of Exile’s Return in 1934, Cowley emerged as the leading chronicler of the Lost Generation, a role he maintained until his death in 1989.

After a Popular Front phase in the ‘30s, when he was editing the back of the book at the New Republic, Cowley began a legendary association with the Viking Press in the ‘40s, scouting talent and editing volumes for its Portable Library. His introduction to the Portable Hemingway (1944) presented readers a Hemingway for the ‘40s—not as a keen-eyed naturalist transcribing the world, nor as a brawny adventurer, school of Jack London (although Cowley bolstered that myth himself with a heroizing piece in Life magazine), but as a writer whose closest kin were Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville, “the haunted and nocturnal writers, the men who dealt in images that were symbols of an inner world.” It was a startling reappraisal of a figure who had been world-famous for decades, yet would become standard. (Hemingway told his friend Colonel Buck Lanham that Cowley was the best critic writing in the U.S.) In 1946 Cowley published the Portable Faulkner, a well-timed intervention that helped rescue the novelist from near oblivion (the Nobel Prize committee took heed).

The Literary Situation briskly takes account of the pretensions of the New Critics (“The New Age of the Rhetoricians”), the paperback revolution (“Cheap Books for the Millions”), the war novels, and other up-to-date matters. An extended “Natural History of the American Writer” traces the species from childhood pursuits to earnings, dress (dark shirts and gray flannel were typical), work habits (including smoking) and domestic habitats, which for the “average” writer would be somewhere within a hundred miles of New York. Since 1931 Cowley and his wife, Muriel, had lived in a converted barn in Sherman, Connecticut, sixty miles from Midtown Manhattan, America’s Grub Street.

In 1954 the most turbulent part of the immediate Postwar had passed. The air was clearer, saner. China was “lost,” the Russians had the bomb (something Harry Truman never expected), but even so the fever dream of McCarthyism was breaking up: its alcoholic eponym would be censured by the Senate in the next year. Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic Party’s once-and-future candidate for president and no firebrand himself, conceded that “moderation is the spirit of the times.” It was thus in a becalmed season that Cowley surveyed the American scene with an eye to the vast changes that had occurred in the last half century, had accelerated during and just after the war, and now seemed to be settling into a pattern unexpectedly bland and desperately decorous. Some broad observations:

Demographic: “The population of the country had doubled in my lifetime: the increase was from 76 million in 1900 to 151 million in 1950…. In proportion to the total population there were more women in 1950, when they first outnumbered the men; there were more persons over sixty and many more white-collar workers, while the numbers of farmers and miners had decreased absolutely as well as relatively. More of the new Americans were living in Michigan, Florida, Texas, and on the Pacific Coast, where the population had been growing faster than elsewhere in the country; all four regions, but especially California, were playing a larger part in literature. In some of the prairie states, the population wasn’t growing at all.

“In almost all the metropolitan areas”—there were 168, as defined by the Census, each boasting at least one city with a population of 50,000 or more—“the suburbs were growing faster than the cities, many of which were standing still.” Unlike anomic urbanites, “The new Americans lived outside the city in communities where they knew their neighbors by name and tried to win their approval. ‘People like people,’ said William Levitt, ‘that’s been our experience,’ speaking for himself and his brother.”

It was also the Levitts’ experience—literally, their prejudice—that white people didn’t want Black people for neighbors. Levittowns—the archetypal postwar “developments”—were effectively closed to African-Americans. (Hispanics and Asians barely figured on the scene outside the Pacific Coast and the thinly populated Southwest, but they would have been unwanted too.) But then, the genteel Progressive Era streetcar suburbs from Ditmas Park in Brooklyn to the Elmwood District in Berkeley were in practice no less exclusive.

Some time in 1948 the balance in what had been an urban nation since 1920 subtly shifted, as the percentage of Americans living in cities of 100,000 or more was outnumbered by those living in the spreading suburbs; the national ambience was going from thronged city streets to tranquil suburban lanes. As opposed to the jarring inequality of the city, material life in the suburban nation was strikingly egalitarian.

“Everyone seemed to be middle class and literate, no matter his trade,” Cowley reports of a season spent in Seattle in 1950. “We lived on a street lined with picture-windowed houses that were owned, not rented, by business people, skilled mechanics, and college professors. The milkman, the dry cleaner for the neighborhood, and the cleaner’s wife were college graduates, as were many of the taxi drivers. There was no longer the gulf that threatened to open in the 1920s between the white-collar classes and men in overalls.” To the contrary, the white-collar worker had slightly fallen in status and prosperity, while “manual workers had risen, both socially and economically; often they had moved into the same streets as the white-collar people and were driving bigger cars.”

Physiognomic: “The physical type was changing along with the social character. Americans were taller than their parents of the same sex, with broader shoulders, deeper chests, narrower hips, and longer legs. Though quicker and more agile, they seem to have less physical endurance; they didn’t excel in marathon races or cross-country skiing.” The rising generation walked less because they were driving cars more; for exercise, or so Cowley says, apparently from observing his son Robert’s friends, they liked a short speedy swim followed by sunbathing on the beach. “One pictured a new race built like herons, with slender legs not designed for walking or climbing, but merely for standing in shallow water.” These notes are more school of Strabo than Darwin, but they don’t stray too far from the empirical mark; people were growing taller and were differently built; and thanks to the new aluminum-based deodorants they even smelled different from their sweaty forebears, or so Gore Vidal maintains somewhere.

Climatic: “The climate was changing, though no one knew how long the process would continue.” This was prescient. In 1946-47 Europe endured the coldest winter since the Middle Ages. To the amazement of botanists, forests were springing up in the bombed-out cities. Wolves were seen on the road from Rome to Naples. But while Europe was enduring the big chill, New York City experienced a historic heat wave. Truman Capote wrote of an August day when “the heat closed in like a hand over a murder victim’s mouth, the city thrashed and twisted.” Along with the television set, the inexpensive window air-conditioner was just about to become a familiar domestic appliance, but the toils of summertime in the city still sped the exodus to the chiller suburbs.

Digitally enhanced photograph of Times Square, Manhattan, New York, July 1949, in the middle of an historic heatwave. Courtesy Shorpy.com

Environmental: “The land itself was changing as its inhabitants were redistributed around the metropolitan centers and along the radiating superhighways. Away from the highways and summer resorts, broad sections of the country were poorer and emptier than they had been in 1900.” An improved “standard of living” came at the cost of environmental degradation. What was once prosperous farmland, as in Westchester County, New York, had been paved, condemned, and excavated to build housing tracts or light-industry, or converted into “airfields, golf links, parking-lots, drive-in theaters, and automobile junkyards.” Along with the despoliation of the landscape came the exhaustion of natural resources: “part of the price for winning World War II had been the iron ore of the Mesabi Range.”

Hibbing, Minnesota, a town of a few thousand set in the Mesabi (a district, not a hilly or mountainous place) had been one of the busiest extractive sites in the world during the war. “Again, let me allude to the tranquility, the remote sylvan calm of this area,” John Gunther wrote in his mammoth survey, Inside U.S.A. (1947). “Then reflect that this is the essential heart of the steel industry of the United States.” Hibbing’s distinguishing feature was an open pit proudly advertised by locals as “the biggest hole ever built by man.” Here, Robert Allen Zimmerman, familiarly Bobby Zimmerman, later Bob Dylan, born in 1941 in neighboring Duluth, moved with his family in 1947 and grew up, amid the greenery and the slag.

“He felt he didn’t fit in, not in Hibbing,” Echo Star Helstrom, the girl from the North Country, told his first biographer, Anthony Scaduto. “I remember, during the time we were together, he would drive down to Minneapolis and come back and tell me how great everybody was down there. ‘Everybody’s with it, down there,’ he’d say. ‘It’s so different from Hibbing. They understand.’”

Few spans in American history have received such mixed notices as the years from 1945 to c. 1974, although in view of what followed, some historians have taken to calling this interval the golden age, or in France, “the thirty golden years.” It was a time of distant conflicts, widely diffused prosperity, and declining inequality, but also, especially at the start, of “containment”— psychological no less than geopolitical.

One historian’s Proud Decades is another’s Dark Ages. What might be called the disputed years begin at the beginning, V-J Day, August 14, 1945. Popular chroniclers, even historians who offer more complex takes elsewhere, reflexively recall V-J as joyous, even “ecstatic,” although it was surely not that for everybody: not for the bereft mourning while others rejoiced. As told by Eric F. Goldman in The Crucial Decade: America, 1945-1955—the first summing-up of time and place by a respectably tenured academic—the celebration of victory over Japan roared cross-country, from waylaid trolley cars in Los Angeles, snake-dancing in staid Salt Lake City, to a night-and-day, day-and-night revel in New York City which at its peak packed two million people into Times Square; the triumphant bulletins on the New York Times building’s electric “zipper” sent up cheers that echoed from the Hudson to the East River. “Americans had quite a celebration,” Goldman recalled,

and yet, in a way, the celebration never really rang true. People were gay, so determinedly gay. The nation was a carnival but the festivities, as a reporter wrote from Chicago, “didn’t seem like so much.” It was such a peculiar peace. … And everybody talked of “the end of the war,” not of victory.

No such muted tones for Marty Jezer, almost forty years later, whose Dark Ages: Life in the United States, 1945- 1960, conjures August 14 in New York City as a contrast between the vast crowd mindlessly celebrating in Times Square—the oblivious “Squares” who might still have been mourning the big band-leader Glenn Miller, lost in a flight over the English Channel in December 1944—and the knowing hepcats jamming at the Three Deuces, “a small cavernous cellar joint on 52nd Street,” where Charlie Parker was playing.

“Who,” writes Jezer, “on that most wonderful of all summer nights, would have imagined that this black bopster genius (and not the celebrants dancing, cheering, kissing, hugging, and winding their way through tons of confetti in long, exuberant conga lines) was attuned to the future, and that his apocalyptic nightmare vision of the American dream was a vision of a world to come.” But it’s unlikely that all that many of the crowd merry-making in Times Square would find the ‘50s so nightmarish; for that matter, Bird’s repertoire in August 1945, which included “Lester Steps In,” was hardly an agonized wail, or at least doesn’t register like one now.

“Over all the victory celebrations,” says Goldman, “the fact of the atomic bomb hung like some eerie haze from another world.” As of that summer night the apocalypse had already come and gone, with details straight out of the Book of Revelations. Europe, said Churchill, was “a rubble heap, a charnel house, a breeding ground of pestilence and hate.” From Monte Cassino and Dresden, Berlin and the Baltic sea, the devastation extended across Eurasia to Manila, with the advance and retreat of vast armies leading to the greatest forced migrations in history, climaxing with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This brutal tearing at the urban fabric of the World Island was not just the background but the precondition of American supremacy, which by the end of the war had left the U.S. at the “summit of the world” (Churchill). It also confirmed New York as the “capital of the 20th century,” ultimate refuge of avant-gardes and scholars fled from Mitteleuropa, the bastion of capital in a world turning socialist, and a Mecca for the ambitious young of all nations.

But the other-directed young especially would be attuned not to ancestral voices but to their “peers,” in the flesh and in the burgeoning media of the mid-century (paperbacks, comic books, jukeboxes, movies, and so on). If their remoter ancestors had spun like tops in their colonial outposts or crushing occupations, the other-directed were like radar dishes, forever attuned to incoming signals.

James T. Patterson’s Grand Expectations: United States, 1945-1974, is a worthy chronicle of the golden age, laden with the authority of being an Oxford history: Its scope is enormous, its judgments rarely surprise or provoke. And, yet, how consistently in the Postwar was history shaped less by “grand expectations” than by expectations frustrated and disappointed!

The grandest of failed expectations from which almost all the significant others would follow was demographic. The vulgarly named “baby boom,” whose numbers would overcrowd the scene in the 1940s and seize the stage in the ‘60s, came as almost a complete surprise to everyone, including those who were busy procreating. David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd, the most famous work of sociology to come out of the ‘40s, was premised on the idea that population growth was slowing and headed to a decline. The crowd would be lonelier because it would be fewer. In this expectation Riesman and his colleagues echoed what had been the conventional wisdom among demographers—always the last to know—since Herbert Hoover commissioned a voluminous statistical study of American society, Recent Social Trends (1933), which projected that the U.S. population would peak at 150 million around 1970, if not sooner, and begin to fall. “The birth rate has been declining in the United States since 1810,” the report concluded, “hence it seems more likely that it will continue to decline until 1970, rather than becoming stationary in 1945, as the maximum [hypothesis] assumes.” That the birth rate would actually dramatically increase after 1945 and remain at a historically high level until 1964 was too fanciful even to consider.

Tracing an S-shaped curve through history, from ancient traditional societies in which birth and death rates are high and stable, to the population explosion that began in Europe in the 17th century, to the present, Riesman identifies the corresponding ideal character types. In a traditional society, character was formed by rules and routines and rituals learned in childhood and rigidly reinforced by society throughout life. Such, Riesman writes, was the case in Europe until the end of the Middle Ages, and so it remained in 1950 “among such enormously different types of people as Hindus and Hopi Indians, Zulus and Chinese, North African Arabs and Balinese.”

The extraordinary increase in population in Europe between 1650 and 1900 occurred at the same time that it was forcibly imposing its civilization abroad. Emerging during the Renaissance and Reformation was a new “inner-directed” character adapted to conquest (“exploration, colonization, and imperialism”), and novel occupational niches at home. Norms and goals “implanted early in life by the elders,” suggests Riesman, keep the conquistadors and the Mr. Gradgrinds “on course,” (so to speak) like an internal gyroscope, even when they are far from home or removed from familiar routines. Thus, Riesman might have noticed, the ideal type flourished in English literature from Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe to Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz.

The prospect of “incipient population decline,” associated with advanced industrial societies, explains a new type of American character, the “other-directed.” At mid-century the other-directed seemed to be “emerging in very recent years in the upper middle-class of our larger cities: more prominent in New York than in Boston, in Los Angeles than in Spokane, in Cincinnati than in Chillicothe”; its most conspicuous members were teenagers, a cohort only recently identified as such in the New York Times Magazine. Young and old, the other-directed were adapted to a society of consumption rather than rapacious accumulation, of leisure rather than hard labor. But the other-directed young especially would be attuned not to ancestral voices but to their “peers,” in the flesh and in the burgeoning media of the mid-century (paperbacks, comic books, jukeboxes, movies, and so on). If their remoter ancestors had spun like tops in their colonial outposts or crushing occupations, the other-directed were like radar dishes, forever attuned to incoming signals. The exemplar here was Holden Caulfield, who in his fictional life would have been a contemporary in the “real” lives of John Updike, Susan Sontag, Philip Roth, and Leonard Michaels, all born in 1932-1933. Holden’s teenaged Midtown Manhattan odyssey in Catcher in the Rye is exactly dated to the winter of 1950.

Riesman, let it be noted, was not so far off in his anatomy of the changing American character; what he got wrong was the numbers, and that would make all the difference, beginning with the signals sent and received in the country of the young.

The last year of the war and the first year or two after was like a month of crazy Sundays. As Norman Mailer, author of The Naked and the Dead, later romanticized,

The life of the nation was intense, of the present—as a lady said, “That was the time when we gave parties that changed people’s lives.” The Forties was a decade when the speed with which one’s own events occurred seemed as rapid as the history of the battlefields, and for the mass of people in America a forced march into a new jungle of emotion was the result.

In the great anaphoric rush of Ginsberg’s “Howl,” the “best minds of my generation”—by which he meant not the highest IQs but rather the most ardent spirits—are those

who created great suicidal dramas on the apartment cliff-banks of

the Hudson under the wartime blue floodlight of the moon

& their heads shall be crowned with laurel in oblivion,

and, a few lines and years later:

who threw their watches off the roof to cast their ballot for

Eternity outside of Time, & alarm clocks fell on their heads

every day for the next decade.

The one who threw the wristwatch—“because we are all living in Eternity now”— was Louis Simpson, the poet, translator, critic, and literary historian. Jamaica-born to Scottish and Russian parents, he was part of the Columbia University literary cadre of ‘40s, had a harrowing war, and like Ginsberg did some time in the madhouse before commencing his career. Meanwhile, the dream factories in Culver City and Burbank were turning out movies with titles like Tomorrow Is Forever and Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, Till the End of Time, and From Here to Eternity.

The Postwar begins by confounding “conventional wisdom” (John Kenneth Galbraith’s useful phrase, not yet coined). Everyone from the New York intellectuals like Delmore Schwartz, who anticipated the novelties and sensations of another Jazz Age, to the Republican politicos (and not a few conservative Democrats), who fondly believed that with the magus-like FDR out of the picture the New Deal would be repealed, to the demographers who got it wrong—all had something to rue.

The never-New Dealers took heart from a widespread presentiment that the nation’s political and social center of gravity was about to be restored to the Midwest, where it belonged. FDR’s unprepossessing successor, the “accidental” Harry S. Truman, was himself a son of the Middle Border who, despite repeated failures in the private sector, retained the prejudices of a small-town businessman. Coming after FDR, Harry Truman would be, Alice Roosevelt Longworth predicted, like a glass of milk chasing a dose of Benzedrine. From the strike wave of 1946 and the war scare of ‘48, through the witch-hunting (encouraged by his attorney general’s infamous list of alleged subversive organizations), the atomic-bomb-rattling, and the Korean War in 1950, Truman’s administration turned out to be one of the most nerve-wracking in modern history. If the majestic FDR had seemed equal to anything history threw at him, Truman, as the young John Updike said, gave the impression of an unnerved riverboat gambler. Yet, Truman was elected president in his own right in 1948, despite a three-way-split in the Democratic Party; the New Deal was (modestly) enlarged, under Truman and his Republican successor, Eisenhower, a politically canny general promoted out of obscurity during the war by FDR.

“There was never a time in American life when private life was so much more attractive than public life,” Cowley sums up. Not so paradoxically, the prevailing egalitarianism was not inconsistent with hedgerows and high fences for those who could afford a place in the country, since the schools and the television set were setting the standards for instruction and entertainment. Inevitably, Tocqueville makes an appearance, having perceived a century before “a sort of enormous pressure of the mind of all upon the individual intelligence.”

Rather than resuming the glitter and excess of the ‘20s, “the first and (perhaps the only) modern decade,” according to the historian John Lukacs, the ‘50s restrained excess and shunned display. “It was characteristic of the Jazz Age that it had no interest in politics at all,” Fitzgerald said, conclusively. But the Jazz Age was a society of spectacles, the greatest since Rome in the first two centuries AD, when, above and beyond the gory contests in the Colosseum, the Romans indulged a passion for drama in vast amphitheaters, chorales boasting thousands of singers, and well-attended public readings that made celebrities of Tacitus and Pliny the Younger. The ‘50s in the U.S. was not without spectacle, typically sporting events; but baseball and football, wrestling and boxing were now viewed at long distance at home, while attendance in person was an atavistic thrill, most gorily at boxing matches.

Significantly, and again mysteriously, the public had begun deserting the splendiferous movie palaces of the ‘20s in advance of national TV broadcasting, as if craving the private spells that the ghostly new medium would afford them. Visiting L.A. at mid-century, the Spanish philosopher Julián Marías was amazed by the limitless sea of houses. “When one is in a residential area, for miles around there is nothing other than homes,” he wrote with evident horror. Yet he needed only to wait for night to peer into the picture windows to see the phosphor glow that connected them. Only apparently turned in on themselves, the houses were little domestic monads linked by the “preordained harmony of television.”

In 1960 Norman Mailer had a different sort of epiphany in Los Angeles while he was covering the Democratic convention for Esquire: the revelation of charisma. A day found him waiting for the arrival of Jack Kennedy on a balcony of the Biltmore Hotel opposite Pershing Square, in L.A.’s notional downtown, “the three-hundred- and-sixty-five days-a-year convention of every junkie, pot-head, pusher, and queen.” The candidate arrives in a convertible, observed by a scrum of television cameras. Mailer writes:

One saw him immediately. He had the deep orange-brown suntan of a ski instructor, and when he smiled at the crowd his teeth were amazingly white and clearly visible at a distance of fifty yards. For one moment he saluted Pershing Square, and Pershing Square saluted him back, the prince and the beggars of glamour staring at one another across a city street, one of those very special moments in the underground history of the world.

Having wondered why the convention seemed so depressed, Mailer realized it was because the Democrats were preparing to nominate a candidate with the aura of a movie star, “and the consequences of that were staggering.” But this mysterious stranger, as Jack Kennedy remained at this hour to most Americans, was destined to be not a movie idol but a television star, and television is a greater mystery than the movies. It is possible to speak of “the whole equation of pictures,” as Fitzgerald does in The Last Tycoon: there is no such calculation for television. But if television was a “cool” medium, per Marshall McLuhan, Jack Kennedy was “positively glacial” (Gore Vidal).

How vivaciously this then dawn-fresh, now lost time is captured in Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: Chapters from the Sixties (1988), and from the perspective of one of those uncanny children and knowing adolescents who people the other-directed fiction of the Postwar. After thirty years, Dream Time still reads convincingly as a mid- century Pilgrim’s Progress to some sort of enlightenment as it proceeds from “Once upon a time in the suburbs” to Mendocino, San Francisco, Berkeley, and an unnamed beach and mountain (Tamalpais?). Along the way, allegorical places, people and things: “The Paradise of Bourgeois Teenagers,” “Acid Revolution,” “The Myth of the Birth of the Hippie,” “Amerika, Amerika,” “The Great Fear,” and “Land’s End.”

In the beginning, in the ‘burbs, “the nine-year-olds stood on the playground talking about Hiroshima.” Their fathers and uncles had been in World War Two; logic compelled World War Three, but pending its missile-borne fury, the future beckoned. “The future was going to be fun,” O’Brien writes, “and American kids were going to have the most fun of all. There would be telephones with picture screens. People would live on the moon under bubble domes. Electronic ramps would glide noiselessly into vast siloes. Everything would be shiny and in bright colors.”

In advance of the bubble domes on the moon, families could live in “glassy houses” on earth. Growing up in the prosperous suburbs was a succession of “big green lawns,” perfect for a child’s star-gazing. “In their life-time men would walk on Mars. They could hardly wait.” As the decade turns, movies set in Italy (La Dolce Vita; Two Weeks in Another Town) promote a Europeanization of American sensibility, exciting to young and middle-aged alike. O’Brien:

Presiding over this shift in manners was the Janus-faced John F. Kennedy. While in one aspect of his being he was unleashing military “advisers” in Vietnam and the CIA at the Bay of Pigs, in another he was simultaneously exemplifying the newborn version of hedonism, consorting with movie actresses and playfully manipulating the erotic shadings of his own public image, as if to say, “I am what you want to be.” … Only President Kennedy suggested the possibility of an American lover capable of competing with Alain Delon or Marcello Mastroianni.

The president’s television address giving “advance notice of the possible erasure of the world” during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 intrudes not only on regular programming but on the romance in which he is starring. It is abject to be waiting in line for a movie when the end of the world is at hand, to be “so submissive, so humiliated.”

When Kennedy is assassinated a year later, the generations compact that the party must, desperately, go on. In Greenwich Village, Bob Dylan, most famous for the civil rights anthem “Blowin’ in the Wind,” is becoming an oracle, his albums searched for revelations, like the Beatles’ and the Rolling Stones’. “Ours is indeed an age of extremity,” Susan Sontag writes in “The Imagination of Disaster,” an essay about science fiction movies. “For we live under the continual threat of two equally fearful, but seemingly opposed, destinies: unremitting banality and inconceivable terror.”

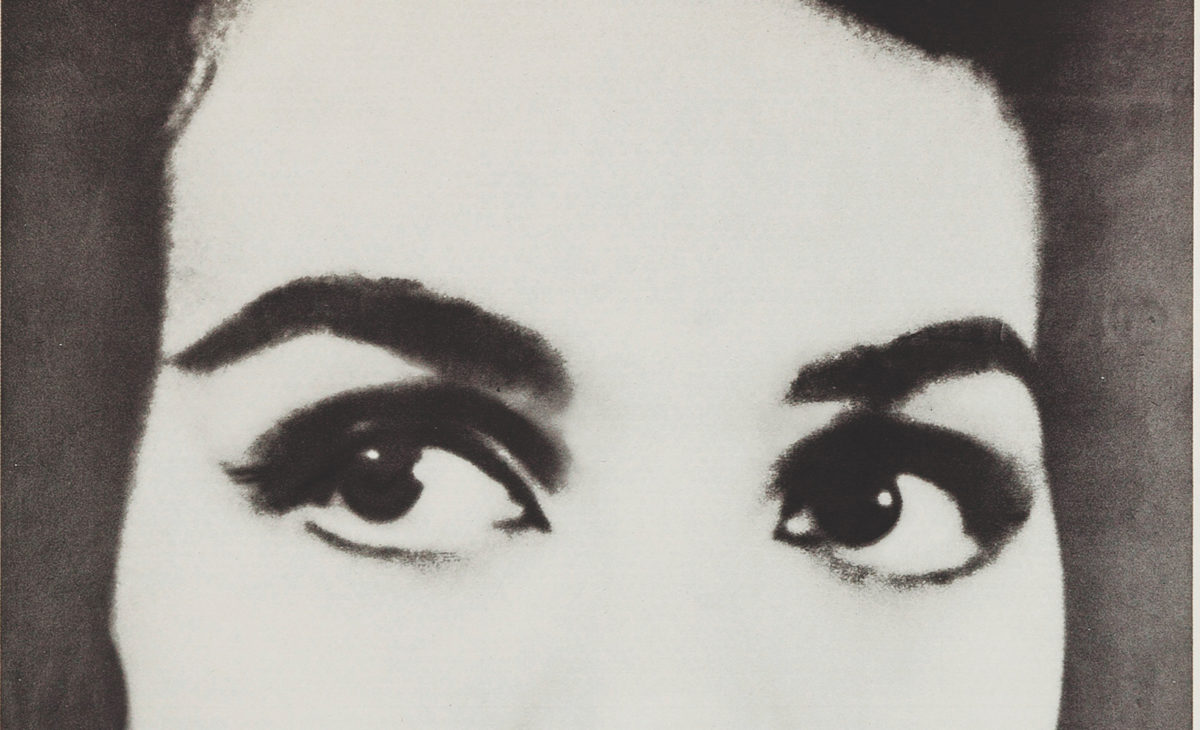

The Postwar has been framed in terms of generations and media, the rise and fall of the New Deal order, the rise and fall of great powers, the American Century, the Jewish Century, the long 20th century and the short 20th century. In the U.S. the movement for Black civil rights, coinciding with decolonization abroad and Cold War tensions at home, demands to be seen in all of the long perspectives; and among the writers who were engaged in the movement, everybody knows James Baldwin’s name. Nobody broadcast on more frequencies.

In Harold Norse’s Memoirs of a Bastard Angel (1989), we encounter Baldwin in Greenwich Village during the war, when his steadiest job was clearing tables at the Calypso café, and nobody knew his name. He despairs when his first novel is rejected. “Look at me! Just look! What do you see? I’m queer, ugly, and black! What future can I possibly have?” These despairs would be short-lived, however. In his second volume of essays, Nobody Knows My Name (1961)—coming on the eve of his celebrity (Another Country would be released the following year)—Baldwin writes,

I had tried, in the States, to convey something of what it felt like to be a Negro and no one had been able to listen: they wanted their romance. And anyway, the really ghastly thing about trying to convey to a white man the reality of the Negro experience has nothing whatever to do with the fact of color, but has to do with this man’s relationship to his own life.

Later, in the years of Baldwin’s great fame, an envious friend tells him, “‘You’ve got it made.’ Jimmy reaction’s was one of horror. ‘What do you mean I’ve got it made?’ he exploded angrily. ‘I’m still black!’ He might have added, for it was equally true, ‘I’m still gay.’”

During his visit to the Bay Area in spring 1963, Baldwin, on a haunting drive around the cool gray city—recorded in the documentary Take This Hammer by the poet, filmmaker, public radio and television pioneer Richard O. Moore—declares there is “no moral distance” between Birmingham, Alabama, where Martin Luther King, Jr., and the SCLC cadres are at this moment confronting Bull Connor, and San Francisco, where “urban renewal” was desolating the Fillmore District. By then, Baldwin’s essays were appearing in the New Yorker, his novels and collected essays were published in hardcover by prestigious Knopf and in ubiquitous paperbacks by Dell, and television producers were discovering how entrancing his hooded eyes and eloquent gestures were to the camera. The mass market in print and the mass audience in television galvanize the civil rights movement, actually enable it.

The 1965 Oxford Union debate between Baldwin and William F. Buckley, Jr., was one of the legendary rhetorical confrontations of the Postwar, and one which the Oxford Union and posterity has declared Baldwin the winner. Back in Berkeley, in 1963, Richard Moore, who introduced the debate on “educational” television, calms Baldwin down for a radio interview in his house on Oregon Street by drawing him a bath and opening a bottle of Johnny Walker Black.

By 1965 the Postwar was happening in California, most tumultuously at the University of California, Berkeley, where the administration was still registering the shock of the Free Speech Movement. In Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Oedipa Maas is coming

through Sather Gate into a plaza teeming with corduroy, denim, bare legs, blonde hair, horn rims, bicycle spokes in the sun, bookbags, swaying card tables, long petitions dangling to earth, posters for undecipherable FSM’s, YAF’s, VDC’s, suds in the fountain, students in nose-to-nose dialogue. … this Berkeley was like no somnolent Siwash out of her own past at all, but more akin to those Far Eastern or Latin American universities you read about, those autonomous culture media where the most beloved of folklores may be brought into doubt, cataclysmic of dissents voiced, suicidal of commitments chosen—the sort that brought governments down.

All that followed of student revolution—a Childhood’s End moment—grew stronger with resistance against the draft (by strict definition the widest spread modern form of slavery), was divided and animated by disputes about strategy in the civil rights movement, by allegiance to the Kennedys, by drug habits or the lack, by elective affinity with the Beatles or the Stones, or Dylan.

A moment comes, O’Brien testifies, when sheer eventfulness and drug-related epiphanies open a transit into eternity. “It is still early 1967. In fact, it’s beginning to seem as if it will always be early 1967, as if such things were now really ready to melt into the new timelessness.” Meanwhile, the biggest event on Earth was the top-down “cultural revolution” in China.

“Is it possible that during the dark night of our empire’s defeat in Cuba and Asia the American story shifted from cheerful familiar farce to Jacobean tragedy—to murder, chaos?”

Gore Vidal

Sober historians deplore the journalistic superstition that history occurs in decades—which, however, history in the 20th century tends to encourage: 1918-1919, end of World War I; 1929, the Wall Street Crash preluding the Great Depression; 1939, World War II (1941, Pearl Harbor). In 1950 the Cold War turned hot in Korea, seeming to confirm the pattern that continued in the “tranquillized Fifties” (Lowell), followed by the riotous ‘60s; and “we did have a sort of consciousness of living in the ‘Sixties’ while they were still going on,” Christopher Hitchens concedes in Hitch-22. “But the Seventies were only the Seventies because they had to have a name. Nullity and anticlimax appeared to close in on all sides.” It took a few years for the walls of the city to stop shaking.

Nicholas von Hoffman wrote of January 20, 1969, that if Nixon had ridden to his inauguration on a horse-drawn gilded carriage the sense of restoration couldn’t have been stronger. But the antiwar movement actually crested during the invasion of Cambodia in spring 1970, and Nixon’s presidency was consumed by Watergate, whose congressional investigation entailed many alarming revelations about the earlier Postwar.

“Is there something our rulers know that we don’t?” Gore Vidal asked in the pages of the New York Review of Books in 1976. “Is it possible that during the dark night of our empire’s defeat in Cuba and Asia the American story shifted from cheerful familiar farce to Jacobean tragedy—to murder, chaos?”

The voters had by then replaced the unelected Gerald Ford with decent Jimmy Carter, whose modest portion of charisma would be unequal to his misfortunes. Reagan’s two terms (“It’s Morning Again in America!”) did constitute a restoration of sorts but more Louis XVIII than Charles II or Napoleon III; now there was a nullity at the center. Channeling T.S. Eliot, Joan Didion would title her account of the Reagan White House “In the Realm of the Fisher King.” Mikhail Gorbachev inadvertently presided over the liquidation of the Russian empire in what Americans called Eastern Europe. The Cold War ended punctually in 1989-91, with the breakup of the Soviet Union. The events inspired Francis Fukayama’s famous essay on “The End of History,” a subtler thesis than is usually conceded.

Malcolm Cowley, who lived throughout this entire span, and might even have heard of the rumor of history’s end before he died, didn’t in the end venture anything as provocative about the future of American or world literature as George Steiner in his essays “A Pythagorean Genre” and “In a Post-Culture,” or Lionel Trilling writing on adversary culture. Rather by the bye, he conceded that printed literature might come to be written and read only by scholars, and the public might read “picture books,” and consume tape-recorded stories, or dramas and serials for television, “or the new medium that will come after it,” all of which were common expectations at the time, and have been, usually in disappointing ways, perfectly fulfilled, according to McLuhan’s perception that the “content” of any medium is another medium. We have enjoyed since the Postwar a second “golden age of television,” which consisted of episodic dramas recapitulating night-time soap operas, and are now supposed to be enthralled by cinematic “universes” based on comic books from the 1930s and ‘40s. As an old-fashioned person of letters, Cowley hoped in his heart that the future of American literature would belong to another great innovator like Hemingway or Faulkner: “the lesser but talented men and women surrounding him will arrange themselves into a new configuration, like iron filings around a magnet.”

California fulfilled Cowley’s expectations of playing a larger role in literature, in part because of his own efforts, most famously shepherding Kerouac’s On the Road into print. The Beat movement’s anni mirabili were 1955-57 in San Francisco and Berkeley, and the Beats remain the only literary movement in America that readers take any sustained interest in except the Lost Generation.

But back to the mid-century. In the teeming pages of Gunther’s Inside U.S.A., there is no more poignant statistic than the fact that after the war “a recent Gallup poll showed that more Americans would prefer to live in Kentucky than anywhere else in the union.” Kentucky! the author wondered, Kentucky, which notwithstanding the legend of Daniel Boone and the gold in Fort Knox, was the 47th state in literacy (only Mississippi was more illiterate). Kentucky, where 97% of farms had no indoor toilets, and population had actually decreased during the war. Why, then, were people going to California when they really wanted to live in Kentucky? It’s a mystery, like so much of what happened in the Postwar; something had gone wrong in the dark fields of the republic. “Whither goest thou, America, in thy shiny new car?” Ginsberg asked. Not Kentucky.

Louis Simpson, who threw his wristwatch off a roof and won a Pulitzer Prize, lived and taught for a while in Berkeley, “troubling the dream coast / With my New York face.” Here he is, in “Lines Written Near San Francisco,” at Land’s End:

Every night, at the end of America

We taste our wine, looking at the Pacific.

How sad it is, the end of America!

READING LIST

A disclaimer: In this sketch I have pilfered from my previous writings on the Postwar, but only when I couldn’t improve on the examples, quotations, or phrasing.

Sources and further reading: Louis Menand’s The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War (New York, 2021) is a monumental intellectual history of America from the war to c.1965. In his notes Menand acknowledges, among other contemporary writers on the period, W. T. Lhamon, Thomas Crow, David Belgrad, Morris Dickstein, Mark Greif, and George Corkin; interestingly he fails to mention early surveyors, once of considerable fame, such as Harold Laski (The American Democracy, 1948) and Max Lerner (America as a Civilization, 1957). Arthur Marwick’s The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, c. 1968-c. 1974) (Oxford and New York, 1998), has a span and a scope comparable to Menand’s. Eric F. Goldman’s The Crucial Decade: America, 1945-1955 was re-issued in an expanded version as The Crucial Decade—and After, 1945-1960 (New York, 1960). Other period histories are John Patrick Diggins, The Proud Decades: America in War and Peace, 1941-1960 and Marty Jezer, The Dark Ages: Life in the United States, 1945-1960 (Boston, 1982). Of the books published in the midst of things, or soon thereafter, Godfrey Hodgson’s America in Our Time: From World War II to Nixon (New York, 1976), still seems to me the most vivid.