A dispatch from the South West forests in Western Australia

One morning in July 2020 I drove three hours to the sawmill town of Nannup. I had been invited to get in the way of some loggers in a neighboring forest called Helms, one of those whitefella names for Wardandi Noongar Country. This “action” was secret and the organizer hadn’t told me where to go, but a message would come later that day. I left Perth before sunrise. A good camper, I had loaded the car with one bottle of water, a carton of vegetables (including a lentil soup mix), Pringles, and three books of nature poems, which, I reasoned, could be used as fire starters if necessary. I didn’t bother with a tent, deciding instead that I would brave the conditions of the car over the forest. The drive was pleasant. The South West is full of paddocks. I didn’t take my time.

When I arrived in Nannup I parked outside the old Hotel and walked the main street. Nannup is a small town, and like any small town in the Australian bush, it doubles to survive. The post office sells lotto tickets. The bakery sells milk. In a gift store you can buy oil paints and oil paintings, as well as toy koalas. And when it comes to hemp, Nannupians, all 1,200 of them, are spoiled: there’s a hemp farm and two hemp stores, perfect if you like your soap green and local. As I walked I kept one eye on the town’s Lilliputian buildings and the other looking for loggers. But it was a Saturday afternoon, quiet as hell, and after five minutes I wondered if I was a ghost: in a gallery and a cafe both proprietors ignored me. When I reached the All Saints Church—it’s no bigger than a bedroom—I turned around.

Days earlier I’d tried to organize a meeting with a local. Someone who could tell me about the town’s timber history. I found the number of the Nannup Historical Society and spoke to a woman with the bush in her voice, dry and brittle. After 11 years in the town, she told me, she still considered herself new. “You have to be born here to be a Nannupian,” she went on. “The community is kind and giving, but won’t give too much personal information.” Secretive, I thought, like me. She told me to be in touch when I was in town, and she’d see if anyone was around, like the old boys at the bar. But her words felt like a warning. Be careful, they seemed to say. I saved her number, but didn’t call again.

On my way back to the car I stopped at a monument of giant saw blades next to the bowling green. Inset over thick panels of wood, the rusty, long toothed blades featured etchings of old Nannup townsfolk from the years of the Great War, those who had died and those who had waited on the dying. Here they were, the pioneers of the town remembered in the tools of their logging past, a past that was still spinning through the native forest where I was about to camp. A history safely contained, hidden from the eyes and nos of the city, out of reach. Just then there was a buzz in my pocket. One of the organizers had posted the location of a meeting place, a cabin in the bush. Finally, a summons.

All of this was new to me—the forest, its lawful undoing, sleeping next to bulldozers—and I felt embarrassed that I had for so long considered myself environmentally conscious. As if sorting my trash and walking to work and having the right opinions about coal made me just.

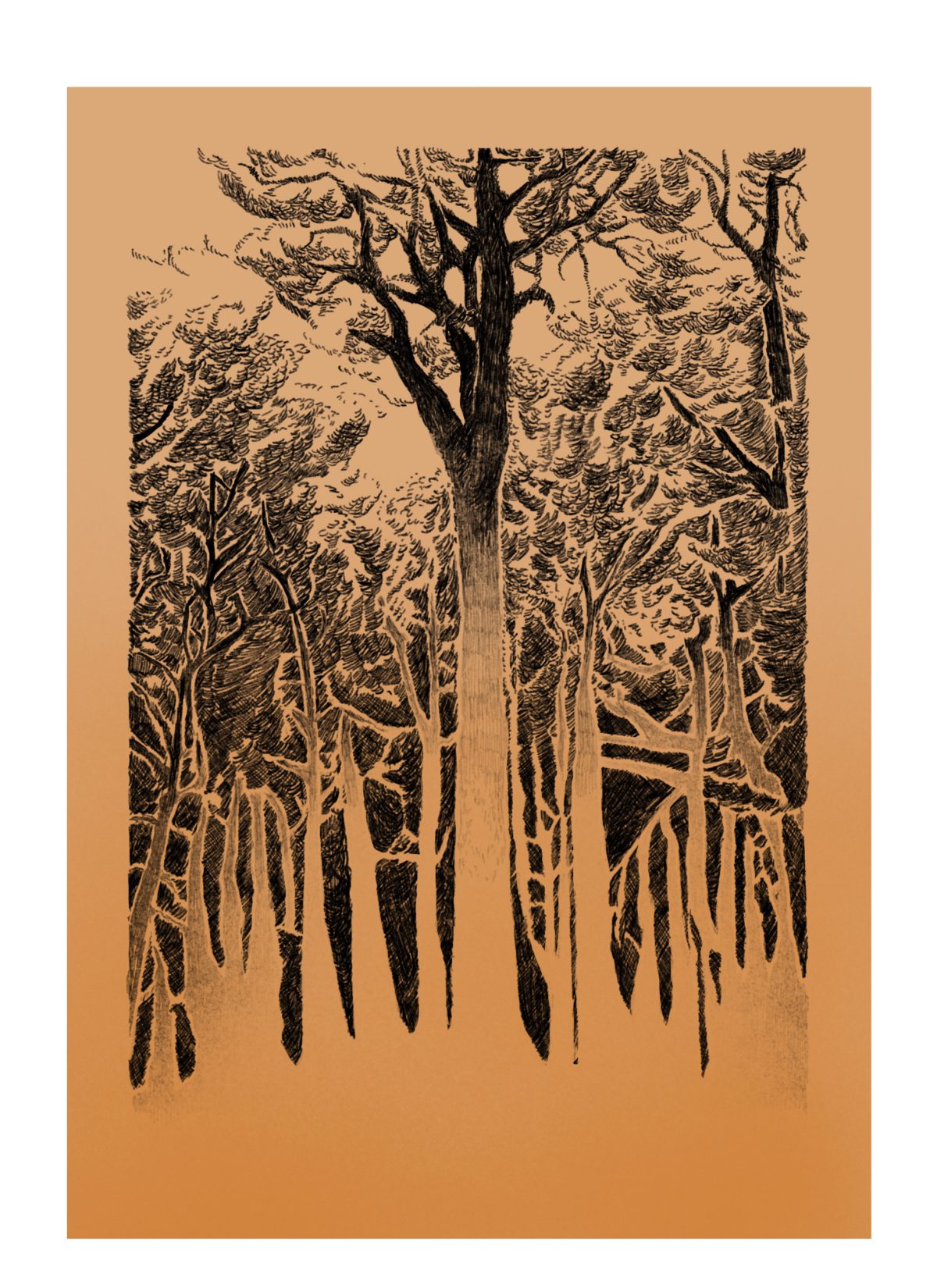

This summons began two years ago when I found the West Australian Forest Alliance outside Perth Station. They were protesting the logging of old-growth Karri trees in Lewin (Bibelmen Noongar Country), about thirty minutes south of Nannup. Karri are magnificent gray eucalypts that can reach 300 feet and host crowns the size of tennis courts. They are native to Western Australia. But thanks to a lousy definition of old-growth, they were being torn down and sold as wood chips and charcoal for a silicon smelter. The Forest Alliance had had enough. They had set up a blockade in Lewin to stop the machines. “Come and see,” they said. I got in the car a few days later.

When I arrived I found a bush camp in the ecotone between ruin and rescue. In ruin were the massive Karri logs, lying like fallen pillars, waiting for that last joyride to the smelter. The rescue effort was a few feet away near the surviving trees. In an act of defiance, the campers had repurposed the felled branches as support poles for a roof, forming a kind of bush hut. Next door was a tent filled with food and supplies, i.e. the “kitchen.” There were water tanks. A makeshift sink. Solar panels. Chairs. Even a wooden floor of salvaged scrap. People were coming and going, making tea, sitting round the fire, having a yarn. Everyone seemed in good spirits. I joined them on their strange reclaimed land.

Jess Beckerling, the convenor of the Forest Alliance, led us on a walk. “A churned up muddy moonscape,” she said of the land stripped by machines. We passed into uncut territory, almost wading through the bush. She pointed out nesting hollows. The notorious snottygobble tree. Then she stopped in front of a lowly Karri stump. It was old, black, and half buried, the remnant of a tree felled long ago. It was why they were there. Only that wasn’t really true. They were there because the West Australian government had written these stumps into law to shore up space for logging. “Where just one tree has been cut down at some time in the past 150 years,” said Jess, “that 2-hectare area of forest no longer qualifies for old-growth status. Forests with all the characteristics of old-growth are excluded on this basis.” It started raining.

It was dark when we returned to camp. Some people went home. I sat by the fire with those who stayed, listening to their stories. Everyone had their reasons for being there. Dom, the mainstay, liked the bush where no one could tell him what to do. Nathan wished the government would transition the logging industry to plantations. “Back in the day they’d come in and take the biggest, straightest tree,” he said. “Now they come and fell the whole lot.” All of this was new to me—the forest, its lawful undoing, sleeping next to bulldozers—and I felt embarrassed that I had for so long considered myself environmentally conscious. As if sorting my trash and walking to work and having the right opinions about coal made me just. But in this heyday of the Anthropocene, being just, I realized, is dirty. It’s crude. And it only works on site. I could march and shout in the city—and I’d served my time—but unless people were here muddying their boots, stinking their jackets with smoke and sweat, and surveying hollows to build evidence for their protection, the machines would keep churning. A few months later their actions would see Lewin removed from the logging plans.

I stayed one night at camp, barely any time to get a feel for the gritty activism I’d flown into. Two weeks later I was actually flying, heading back to the United States for work and love, guileless and guilty on a carbon-oozing jet plane. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the trees in Lewin, and people like Jess and Dom who had made forest protection their life. Strangely, it was there, on that contested ground zero, that I felt most at home. I stayed in touch. And when I returned to Western Australia last year, I messaged a friend at the Alliance. She invited me to an event where I heard about another forest known as Helms. A camp had been set up to protect its Jarrah trees and wildlife, but this time the police shut it down. The Alliance was planning a response. “Don’t tell anyone,” my friend said. I drove to Nannup a few days later.

I arrived at the cabin feeling lost, damned, and confused, like some kind of disaffected tourist who couldn’t remember why he’d left the hotel. Smoke was rising from a chimney. It was getting dark. What was I walking into? Inside I found three women in front of the fireplace. They were whispering, and when they saw me I couldn’t tell if they were pleased or disappointed. “Is this the meeting place for the action?” I asked. One of them nodded, invited me over, and introduced herself as Dara. She said I might like to choose a bed while the options were good. I found a dusty single by the window, set my things down, and joined them by the fire. Dara had come from Busselton. The others, Iris and Daisy, lived nearby. So far I was the only one from the big smoke.

Each of them had a vague idea of the plans for the weekend, and they filled me in as best they could. The action would begin the following afternoon, Sunday, and revolve around Dom and Mace, who were on their way down from Perth. In the evening we’d drive to the forest and set up a temporary camp. Dom, who I remembered from Lewin, would climb an old Jarrah tree in the forest and stay on a platform held up by a cable tied to a bulldozer. Meanwhile Mace would circle their arms around part of another bulldozer, interlocking both hands in a steel pipe, embracing the thing for hours. The rest of us were the support crew, the caretakers of transgression. It was expected that the loggers would find us early Monday morning. They would notify the police. Dom and Mace would be arrested. A film crew would capture everything.

It seemed like a solid plan, but listening to Iris and Daisy, I got the sense that they were a little skeptical, maybe even resentful. They’d been camping in Helms for months before their blockade was shut down, doing it tough in 47 degrees Celsius heat while much of the country was burning around them. Who were we, they seemed to say, flying in, getting our faces on TV, and flying out? I wanted to agree, and maybe they had a point, but I was so fresh that I just nodded and said, “I see.” The rest of the night passed quickly. Dom and Mace arrived late, and a few others trickled in, like Paul in his orange bus named Delilah. The next morning a group went to Helms to scout the area for machines and a climbable tree. When they returned we gathered in the cabin to strategise. The fireplace was leaking smoke.

“People have to see what’s going on,” he said. “There needs to be more outrage. More pressure, politically, and then we’ll pull something off.”

Dom came around with a plastic bowl for our phones, and for the next hour we assigned roles and talked logistics. Two “wallabies” would disperse in the forest in the morning to watch for moving machines. There was on-ground support personnel. The police liaisons. Hoisters. Cooks. A person holding an umbrella above the camera. I put my hand up for a media role, which meant I was suddenly responsible for getting vision to the press. We covered legalities, the consequences of civil disobedience, and how to talk to the loggers: “Oh, we didn’t know you were working here. Don’t mind us!” Everyone understood they were committing an arrestable offence. It was around 4pm when we left the cabin. Cold. The light fading West. We filed onto the road in a motley convoy seven cars deep. To get to the forest we had to drive through Nannup. It was still ghostly. No one saw us.

On our way we passed rich native forest, trees large and luminous on both sides of the road. If I didn’t know better, I might have thought nothing was wrong. But these roadside trees are, in the words of the West Australian poet Nandi Chinna, a “thin façade.” As she writes in Forest Family, “Behind the majestic roadside strips of jarrah, marri, and karri lie the clear-fell forest coupes scoured like gaping wounds in the landscape.” It didn’t take us long to find our wound. About fifteen minutes outside of Nannup we turned down a dirt road. We passed a bulldozer. Then another. Soon the trees started thinning. The sky grew large. The façade fell away. When our convoy slowed down I knew that we had arrived.

We left our cars and lay claim to the clearing. It was very quiet. I noticed a smell in the air, a sweat of soil, sap, and slit leaves. Waiting between two machines was a long pyre of logs, many of them marked with “CH,” a sign of their charcoal fate. A lone Jarrah stood tall above the logs, ancient and undisturbed, a consolation home for the cockatoos who nest in these parts. “Lucky birds!” someone said, wet with sarcasm. The crew had chosen this tree for Dom because it was close to one of the bulldozers. With little light remaining, and rain brewing, he went up without delay. After we hoisted his platform and anchored it to the machine, he got in his sleeping bag and swayed to bed. On the other side of the clearing Mace had been getting intimate with the other dozer, locking themselves in its arms above the blade. We raised a tarp for ourselves.

The night moved slowly. I tried sleeping in the car, but I kept waking to dreams of loggers at my window. I went back to the tarp where people were talking and Dara was cooking chips over the fire. I met a guy named Ray. He was in his sixties, fit, with short gray hair. For the past month he’d been camping here, often alone. Before sunrise he’d wake to the sound of whirring, dress in camouflage, and chase after the machines. He was filming them. “People have to see what’s going on,” he said. “There needs to be more outrage. More pressure, politically, and then we’ll pull something off.” I asked him what it was like chasing a falling forest. He told me the hardest part was leaving. He’d turn to the trees and say, Sorry. “Sorry I can’t do for you what you do for me. Sorry my culture doesn’t understand what’s important.” The loggers found us in the morning. Dom and Mace were arrested. We made the evening news. Two days later the machines went back to work.

Postscript

“Perth” is the British name for the unceded country of the

Whadjuk Noongar. So too is “Lewin,” which names the country

of the Bibelmen Noongar. “Helms” names the country of the

Wardandi and Bibelmen Noongar. “Nannup” is a Noongar word,

said to mean “stopping place.” “Jarrah” (djarraly) and “Karri”

are Noongar words. The Department of Parks and Wildlife spins

its forest management as “ecologically sustainable,” with one

objective “to protect and conserve the value of our forests to

the culture and heritage of Aboriginal people.” This objective is

unapologetically delusional.