What do we mean by “Oxford philosophy”—aka “Oxford linguistic philosophy,” “Oxford analytical philosophy”?

According to the historian of a philosophical movement that he dates from 1900 to 1960, it was all about “a terribly serious adventure” (drawing on the thoughts of physicist Ernest Nagel). Whence the title to Nikhil Krishnan’s survey of the evolution of a way of doing philosophy that, spawned in that magnificent city-state of Oxford, mother to all Anglophone academic institutions (not excluding Cambridge and the latter’s irascible infants at Harvard and Berkeley), subsequently flooded that same Anglophone academic world from the 1960s on with its priorities, prejudices, and eccentricities—and with only relatively recent hints at a final, thankful ebbing.

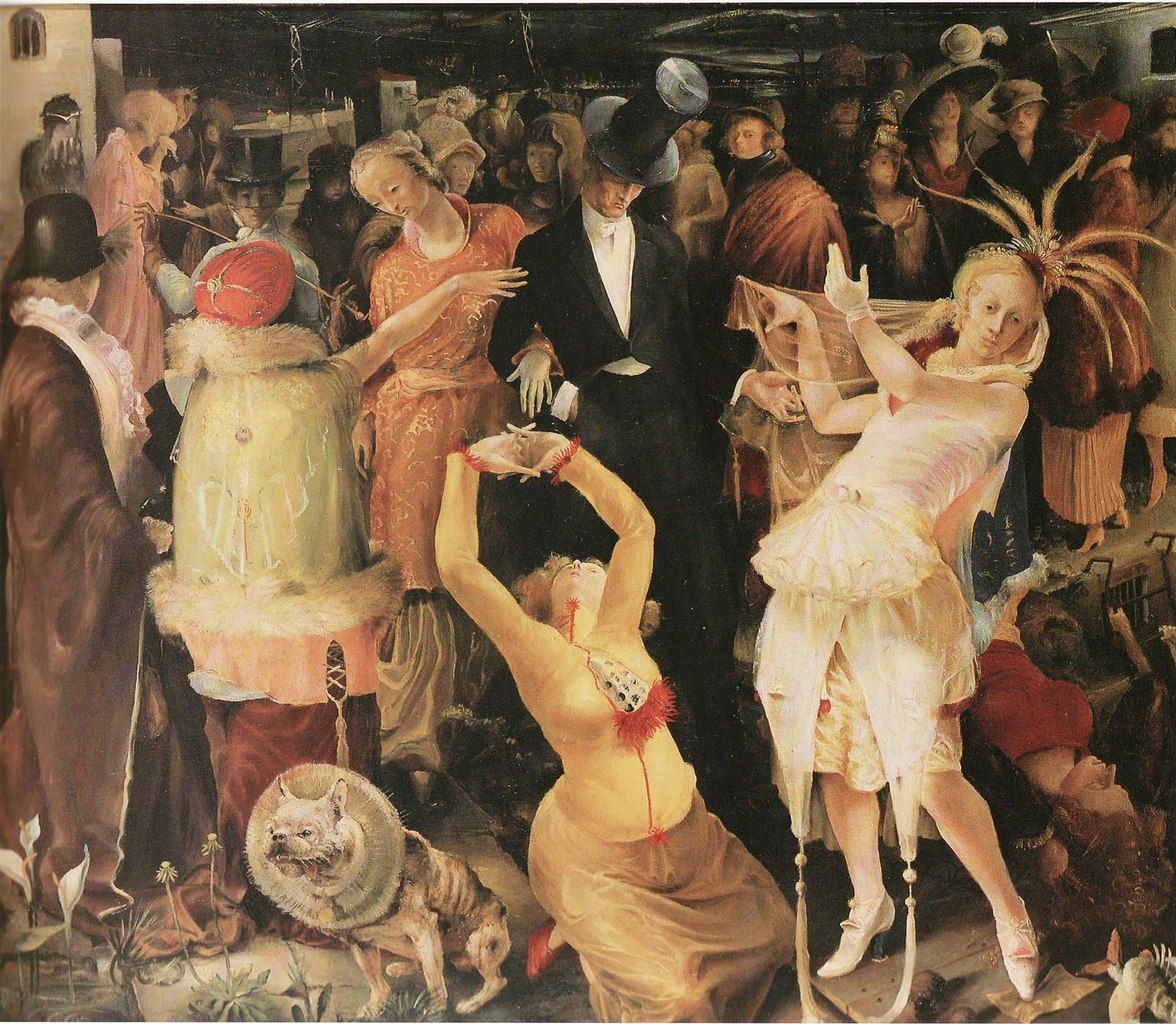

An Adventure rooted in endless intellectual flurries around the central task: “what do we mean by saying…?” Ultimately the answer, if answer there was, would be: diversity, discontinuity, discrepancy. But not before some worthy exceptions could be recorded. In handling the range and specificities of his inquiry, Krishnan candidly chooses as his “basic unit of organization” the “anecdote.” This runs the risk of splaying out a bevy of quasi-prurient tidbits. Thus the warden of Wadham College Maurice Bowra specifies as his standard for applicants: “clever boys, interesting boys, pretty boys—no shits.” Renowned German classicist Eduard Fraenkel enjoys his bit of “energetic pawing,” at least one victim, Mary Wilson (future “Warnock”), forced to undergo the humiliation of “a long series of fumblings with the buttons on her blouse.” While at Christchurch College roué A. J. Ayer avidly brings in “the booze and guests (only men allowed),” with philosophy notable Gilbert Ryle drinking “like a champion” as he downs “a pint of beer in five seconds,” even while the “discussion” rambles on along “naughty but learned epigrams in dead languages.” After all, is this not the very same moral environment in which Alice had in an earlier generation pranced through her wacko adventures in Wonderland?

An Adventure rooted in endless intellectual flurries around the central task: “what do we mean by saying…?” In handling the range and specificities of his inquiry, Krishnan candidly chooses as his “basic unit of organization” the “anecdote.”

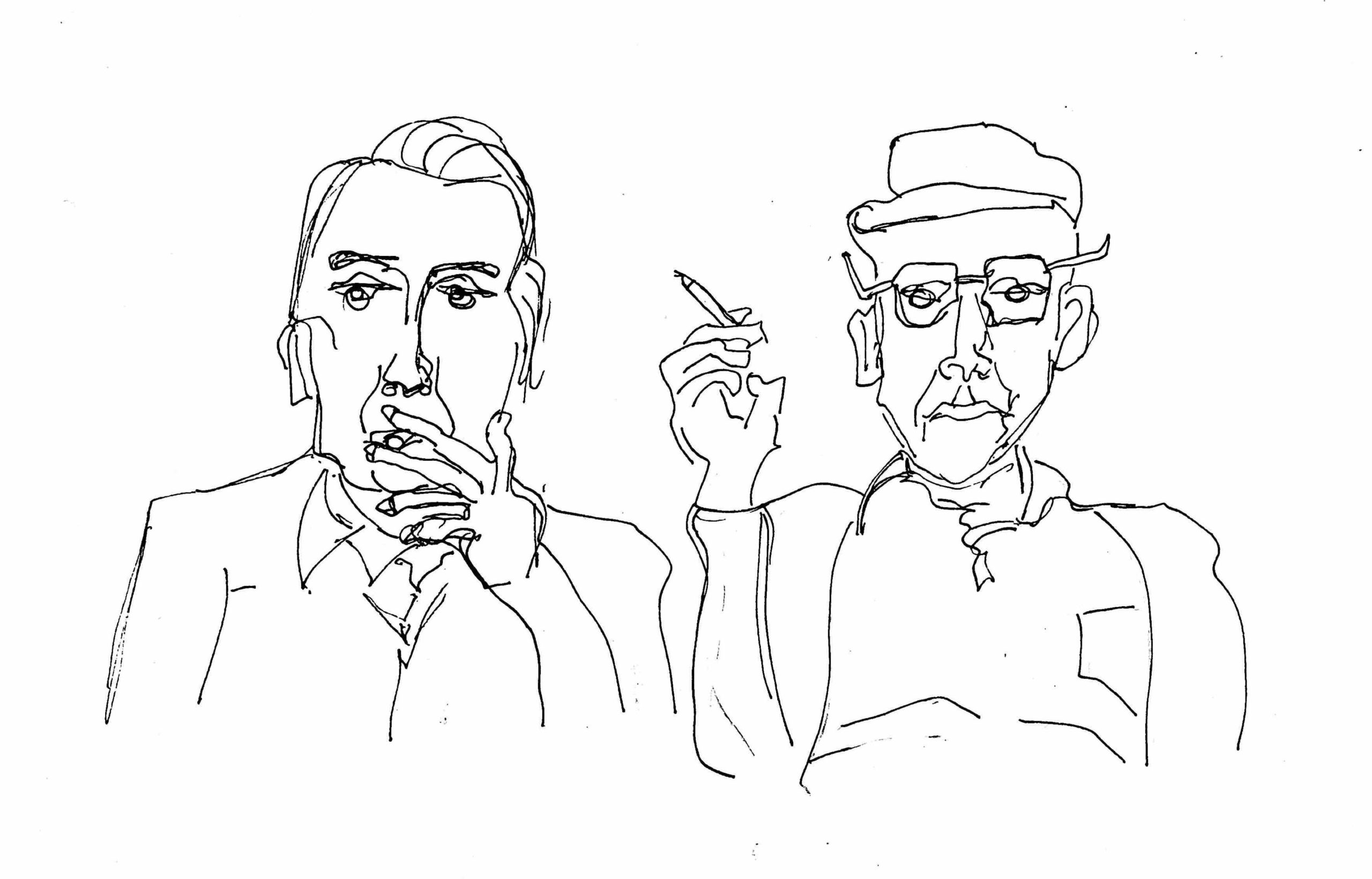

Fortunately, Krishnan is equally ready and capable of rounding out the more serious resonances of the extensive series of philosophical agons highlighting his Oxford time period: Viennese logical positivist convert A. J. Ayer taking on that imperturbable defender of Common Sense J. L. Austin, Wittgensteinian acolyte Elizabeth Anscombe reducing to epistemological rubble the ethical command theories of R. M. Hare, indeed a whole series of critiques of the Oxford school from within by Bernard Williams, Herbert Marcuse, and Stanley Cavell. Whether petty or (potentially) profound this Oxford way of doing philosophy exhilarated insiders and guests, helping to turn Oxford into “the most influential philosophy department in the world for at least ten years.”

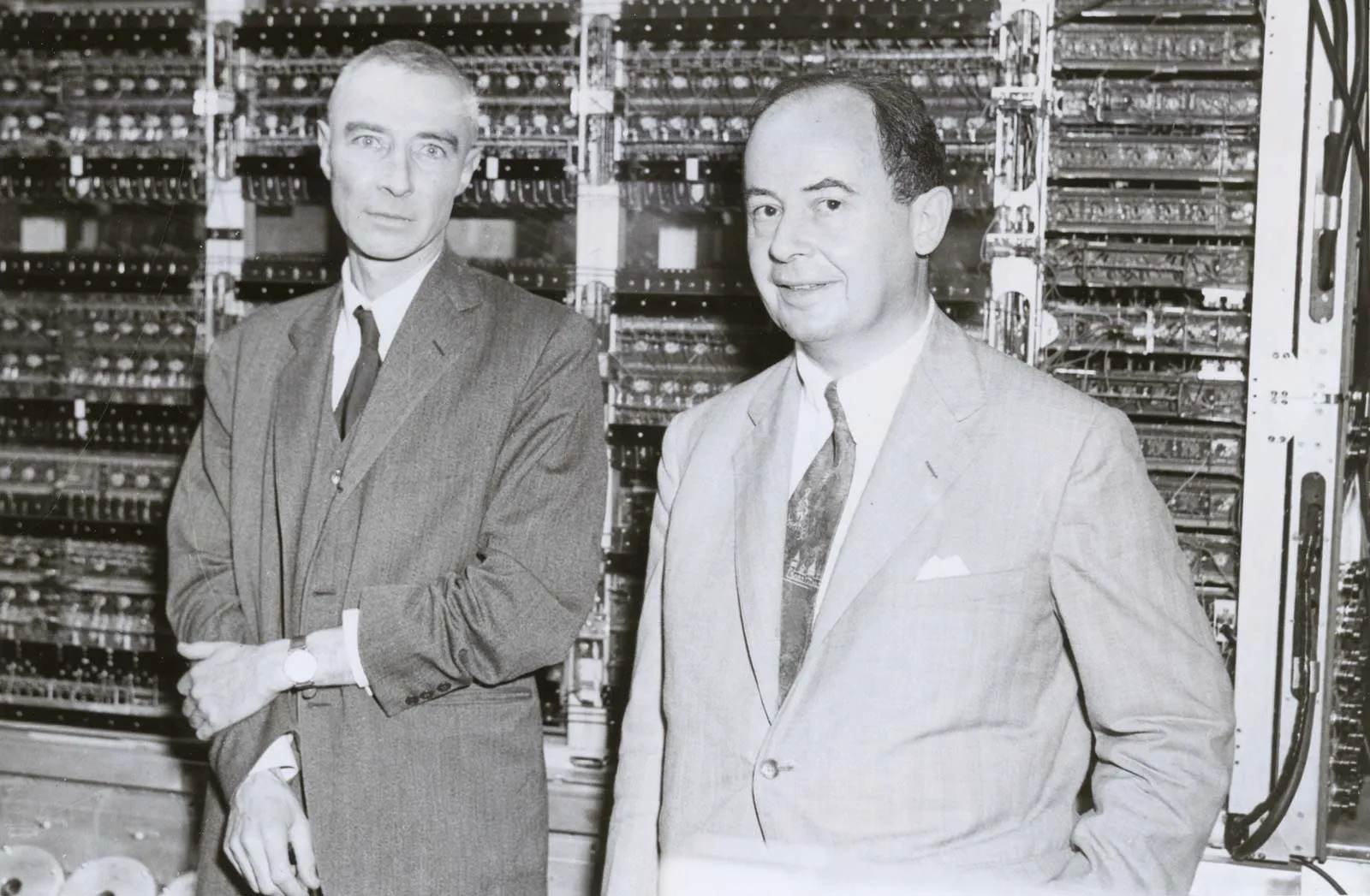

How then to frame Krishnan’s account? One necessarily begins with Krishnan’s perennial hero: J. L. Austin; indeed, Krishnan’s closing date 1960 sanctifies Austin’s unexpectedly early death. Austin, as a contemporaneous intellectual biography on Austin by M. W. Rowe more thoroughly recounts, had a remarkable career, captured in Krishnan’s narrative utilization of the twin motifs “philosophy and war.” First came the “war”: Austin’s intelligence work, particularly regarding D-Day itself, helped save thousands of lives and then helped guide Allied troops into Europe until the final surrender. He was, indeed, according to Rowe, “amongst the leading British Intelligence officers of the Second World War.” Then followed the “philosophy” as postwar Oxford absorbed the impact of Austin’s project to approach philosophical problems by applying techniques acquired through military operations—from disciplined meetings, breaking down of topics through collective attacks, to submission of extensive reports. True, over time that approach became considerably more relaxed, more “Socratic,” but Austin’s towering presence and personality sharply shaped how postwar Oxford philosophers should necessarily set about their tasks.

What then was the philosophical import of Austin’s labors? Had he lived, the most likely candidate would have been a “linguistic phenomenology” mixing linguistics, semantics, and even sound symbolism, or as fellow philosopher P. F. Strawson suggests: “a general classificatory theory of acts of linguistic communication”—all to be fortified by what might well have been, shortly before his early death from lung cancer, Austin’s likely move to the University of California, Berkeley. Is this enough to highlight Austin as the core of what became Oxford linguistic or analytical philosophy? Fortunately, Krishnan’s overview is far more generous, and other figures merit an almost comparable kudos.

Of them Gilbert Ryle stands out, if only for publishing the first book, The Concept of Mind (1949), announcing to the philosophical world the emergence of a distinctly Oxford mode of philosophizing (Austin’s immediate post-1946 contributions largely came out in later edited publications). Krishnan rummages around the point of Ryle’s rant against any philosophy still strongly stained by the Cartesian distinctions of body and mind (“the Ghost in the Machine”) before coming up with Ryle’s contribution to the discussion. All such distinctions betray nothing less than a “category” mistake: “the presentation of fact belonging to one category in the idioms appropriate to another.” No less remarkably, the book depends on the epigram for its arguments as Ryle piles them up, less to support arguments than to elicit characters “like a novel set at the village fête.”

Then there is that perpetual gadfly A. J. Ayer whose Language, Truth and Logic (1936) would drill Oxonians to entertain the sublimity of a reductionist epistemology dismissive largely of ethics, aesthetics, and especially religion. Ayer’s campaigns kept everyone on their common-sense toes, especially after he ascended in 1959 to the Oxford chair of logic when he eventually pieced together his somewhat rambling version of his favored Bertrand Russell’s philosophical pragmatics. And perhaps most significant for gender concerns, Krishnan judiciously shows how the temporary wartime conditions that denuded Oxford of its male components allowed women philosophers to flourish. Although the postwar did bring back the males and a bit of retreat, such female philosophy stalwarts as Elizabeth Anscombe, Mary Scrutton (future "Midgley"), Iris Murdoch and Philippa Foote, among others, continued to make powerful future contributions to ethical and political theorizing.

Like utilizing Cerný’s scale exercises before embarking on Mozart’s keyboard masterpieces, the Austin-Ryle combo was probably therapeutic for serving the more substantive endeavors to follow by the date of Krishnan’s 1960 closure. These included Isaiah Berlin’s provocative 1958 distinction between “positive” and “negative” political liberty, Stuart Hampshire’s 1959 robust rereading of the relations between thought and action or intention, H. L. A. Hart’s 1961 influential rejection of a command basis for law, and, most importantly, P. F. Strawson’s “wild” 1959 bid to articulate, within the severe terms of contemporary analytical theorizing, a genuine metaphysics, however “descriptive.”

Nonetheless, if the aim is to genuinely draw out the historical impact of Oxford philosophy, recognizing this advance is also to productively tamper with Krishnan’s bracketings, for it is more helpful to skip past the somewhat arbitrary choice of Austin’s 1960 death in order to extend the story all the way to the early 1970s. Indeed, Krishnan’s own preferred eight Oxford analytical classics (besides works by Anscombe, Austin, Ayer, Hampshire, Ryle, and Strawson) include two—by Iris Murdoch and by Bernard Williams—that were only published in the early 1970s. This wider span brings, in its turn, a further concern about Krishnan’s coverage. Although he does raise political events here and there, no consistent account of the story of post-World War II Britain, a power that was moving grudgingly from the decline and collapse of one of the world’s more imposing empires to a more modest membership into a larger European Union by 1973-1975, is provided to undergird what was happening to Oxford itself. In this regard Krishnan even fails to cover in sufficient clarity important changes to the Oxford world proper since his chosen 1900s. From Evelyn Waugh’s “city of aquatint” occupied by only some thousand primarily male aesthetes, through the later postwar jump in numbers driven by a massive influx of veterans, to the 1966 Franks Commission Report spanking Oxford for its furtiveness, relative neglect of research, and lack of “social justice,” the university rode squall after squall, the hurricane eye of which could only be occupied for so long by Krishnan’s cultural world.

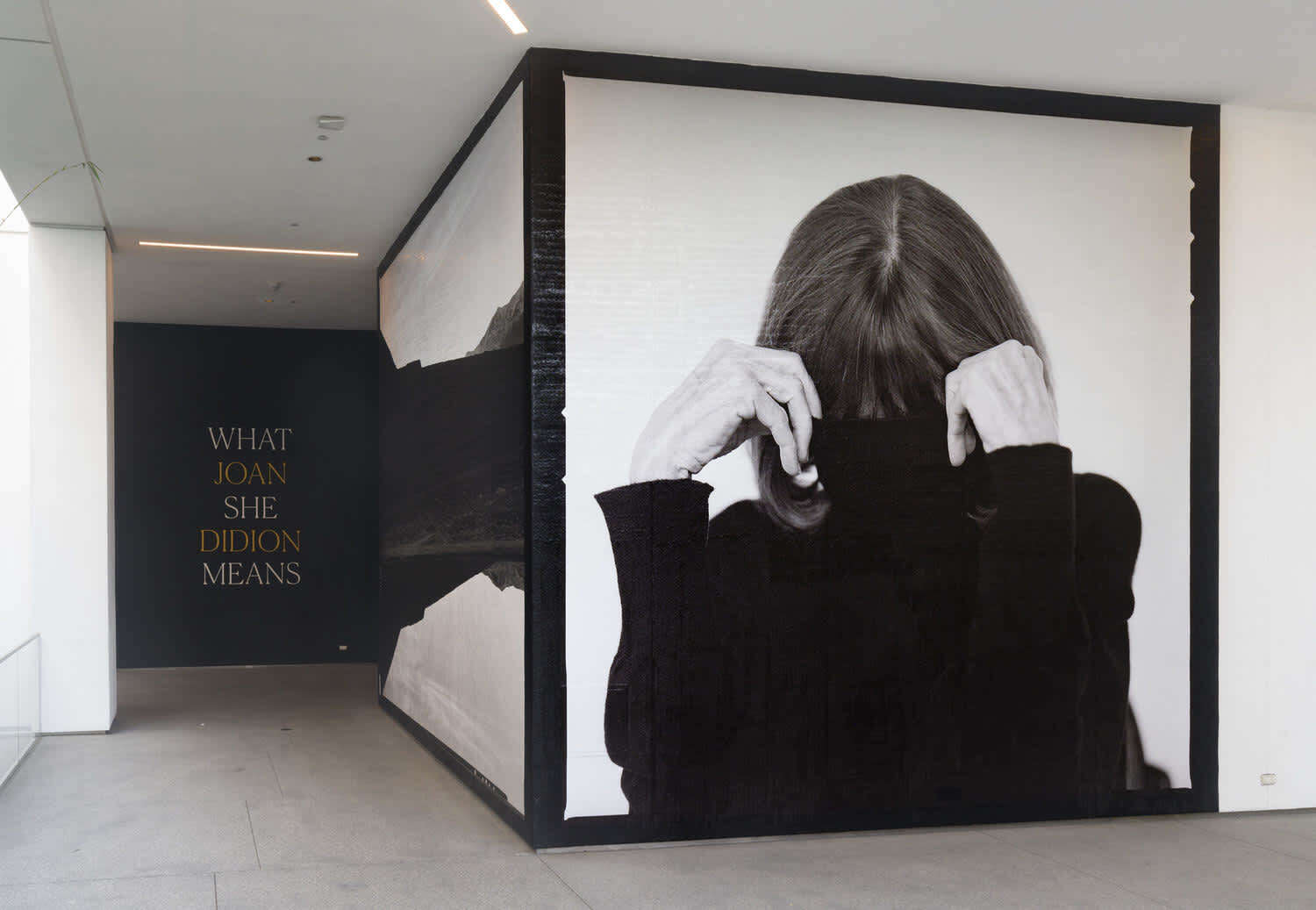

Krishnan’s account should have been more charitable to the outsider reader who may be understandably ignorant of the strange world that has been “Oxford” ever since its probable origins around 1171.... One is thrown into a world comprising a very unique compromise and contestation between something called a University and a bevy of semi-autonomous Colleges. For that matter, Krishnan’s account should have been more charitable to the outsider reader who may be understandably ignorant of the strange world that has been “Oxford” ever since its probable origins around 1171—incidentally a full half-millennium before America’s 1636 Harvard. One is thrown into a world comprising a very unique compromise and contestation between something called a University and a bevy of semi-autonomous Colleges—some obscenely rich for having themselves functioned since, as in the case of Merton College, 1264—going through changes and refashionings that have absorbed late Medieval, Renaissance, Jacobin, Enlightenment, Modern, and—perhaps surprisingly—prosperous Contemporary factors. This Ship of erudite Fools lets outsiders into only some of its idiosyncrasies—that same outsider might consult in this regard the crochety account of Sixties politics by the “anonymously” scribbled Letters of Mercurius (1970), no doubt penned by that erstwhile gossip historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, and although Krishnan’s own anecdotal report has us occasionally wandering down the High to Magdalen or Merton or Christchurch Colleges, he, or his publishers, have anyway failed to be sufficiently generous with anything like a bird's-eye map of Oxford or relevant photos of his participants. Unless the history of contemporary Britain—which after all continued to be ruled by a host of Oxford graduates as prime ministers—and something like an overview of the phenomenon of Oxford itself as a literally millennial culture is brought into play, the narrower story of what Oxford analytical philosophy was about becomes unnecessarily blurred.

In any event, there was much else going on in Oxford philosophizing, despite all the “meanings” that the analytical philosophers hoped to extract from “thought.” The proud home of Hegelianism in its previous epochs under such luminaries as F. H. Bradley (whom T. S. Eliot worshipped), Hegel never went away entirely even during analytical philosophy’s acme period. Merton College warden and Hegelian G. R. G. Mure continued to write voluminously on his Master, Oxford philosopher Anthony Quinton calling his 1965 Hegel book “the best short book on Hegel” since 1883, while Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor then followed up with his massive Hegel study of 1975, earning him Isaiah Berlin’s chair and warming it for his own successor G. A. Cohen, the intrepid philosopher of Hegel's own acolyte Karl Marx.

All in all though, Krishan shows good taste in leaving us with the brightest analytical product of them all: “if Oxford philosophy could be embodied in one person, that person was Peter Strawson.” After all, Strawson could handle the ruckus around the early-century logical debates by his nuanced handling of, e.g., Bertrand Russell’s logic through one that both recognized recent gains in logical theory and highlighted continued respect for traditional Aristotelian logic; he had no fears about refocusing on the two greatest philosophers in the tradition, Aristotle and Kant, by calling on the latter for an actual metaphysics that grounded reality firmly in bodily experience within a spatio-temporal framework; and he continued to campaign for a “realism and catholic naturalism” that could be fairly added to the great Canon. That is more than can be claimed for (some of) the others, and accords Oxford analytical philosophy a permanence that it might not otherwise entirely merit.

A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford 1900-1960

by Nikhil Krishnan

Random House, 2023

$28.99