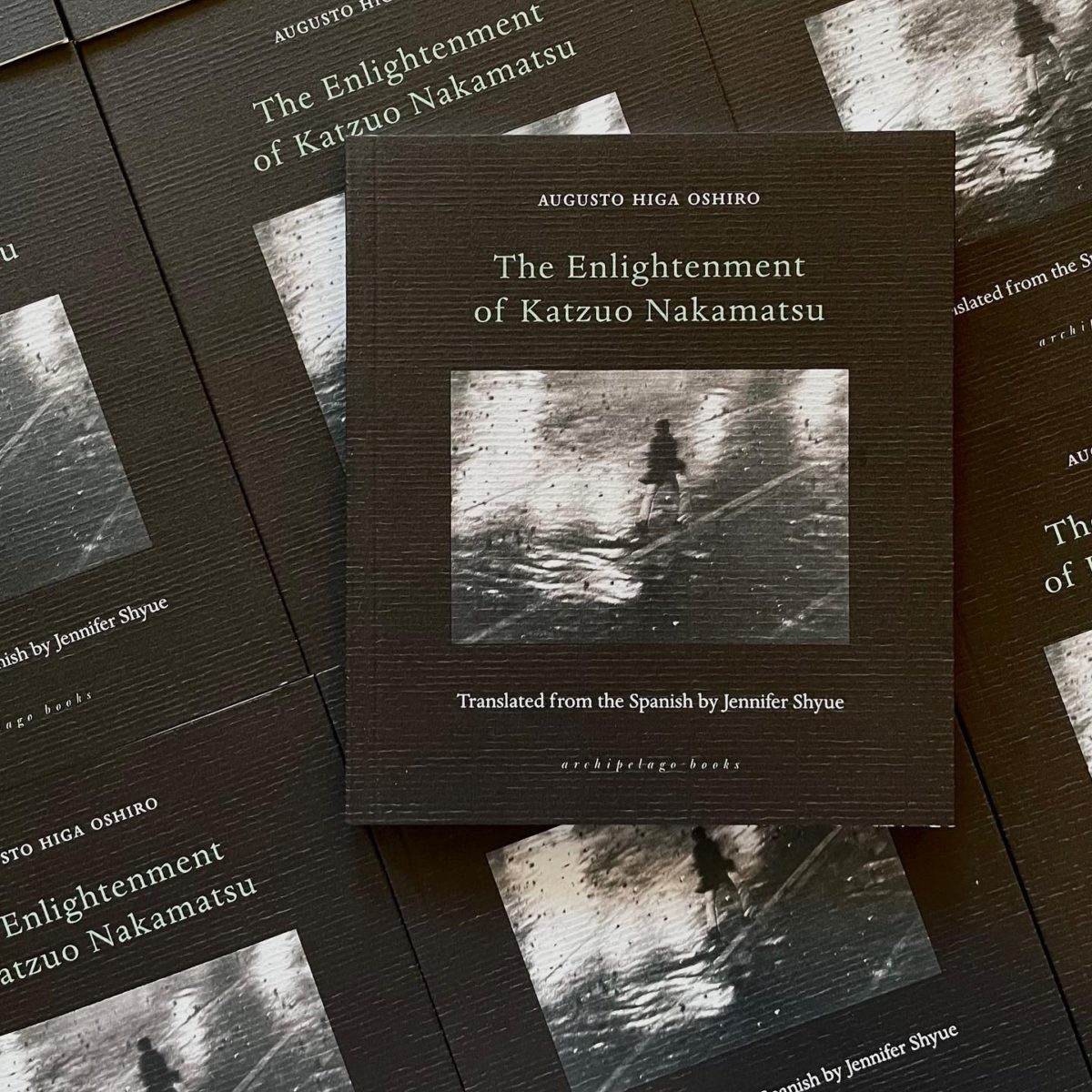

The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu by Augusto Higa Oshiro

The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu

by Augusto Higa Oshiro, transl. by Jennifer Shyue

Archipelago Books, 2023

$18.00

The end of the 19th century saw Japanese immigrants traveling en masse to Peru. Initially, they went to work in mines and on sugar plantations, but many established themselves in middle class working sectors. As the 20th century began, Peru’s Japanese community had grown to include lawyers, business owners, and respected blue collar workers. But the start of the Second World War saw a strong anti-Japanese sentiment spread across Peru, which reached its peak following the Pearl Harbor attack. Japanese businesses and schools were burnt to the ground as the United States ordered the arrest of Japanese citizens in a host of Latin American countries. Many arrestees were deported to internment camps in the US.

Augusto Higa Oshiro, the son of immigrants from Okinawa, grew up in the working class district of La Victoria, Lima in the 1950s and ‘60s. Keen to immortalize the markets and streets that punctuated his childhood, he aligned himself with the Grupo Narración, who set out to represent marginalized communities through working class Lima. The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu (La iluminación de Katzuo Nakamatsu), originally published in Spanish in 2008 and now available in an English translation by Jennifer Shyue, addresses the racial fracturing that the Nisei (second generation Japanese immigrants) of Peru suffered. The eponymous protagonist is a product of his Japanese heritage, though his ancestry is more often grounds for shame and humiliation rather than pride.

The novel opens with a 58-year-old Nakamatsu suddenly and unexpectedly overcome by a fatalism about his end of days, his “untimely lot [which] slid[e]s him to the brink of suicide.” He puts his passing up against the “larger cosmic equilibrium” and decides that his only recourse is to succumb to it. Soon he is “unceremoniously” let go from his professorship at an unnamed university “because of his age.” Without any further responsibilities, Nakamatsu drifts away from any practical concerns toward his death. He has some personal projects—a study of Peruvian Metaphysical poet Martín Adán, and a biographical recounting of Japanese families in Peru—but these remain incomplete on account of his laziness. With his ambitions drained, Nakamatsu plans his suicide and spirals into madness.

A product of his ancestor’s diaspora, Nakamatsu finds himself fractured between two worlds. His Japanese self—a considerable chunk of his cultural makeup—is entrenched. However, this facet of his identity is more often than not the root of his self-hatred; his inability to get private feelings across, his fatalism are explained away as mere “ancestral sentiment[s].” His problems are inherently Japanese, he believes, and heightened by his Nisei status. At the same time, he feels isolated from the rest of the Japanese community in Lima. Nakamatsu is disposed to “the rigour of ideas and the search for a voice of his own,” values he believes are diametrically opposed to those of his old friends and siblings. In this liminal state between self-hatred and misanthropy, Nakamatsu is left without anyone to turn to, and can only look upon himself with shame. His total resignation in the face of death comes as no surprise, given his circumstance.

Nakamatsu reminds me of Clarice Lispector’s Lóri (An Apprenticeship): both live away from home, and their emotional response to this distance fills them with self-hatred, as well as a metaphysical angst; for a person without a country, the base act of being becomes an intricate task, something that one is conscious of, something that appears teachable. Both characters are alienated from the social worlds they are in, and misinterpret their inability to integrate by neurotically positing intricate laws and practices of living that simply escape them, as if living were a skill that required book learning and muscle memory. Lóri fears it is her lot in life to be “cosmically different” and uninvolved in life. Both allow their neuroticisms to make them passengers in life. Or, as Higa Oshiro puts it himself: “raving at the margins, walled off from the world, majestic and destitute.” They are caught between worlds, without a tangible entry point to either.

As the story progresses, Nakamatsu’s self begins to unravel as he embraces an ascetic approach to his demise. The story distances itself from his perspective, emphasizing this self-abnegation; what appeared to be an omniscient third person narrator pulls the curtain back, revealing an old colleague simply reporting on his friend’s worsening condition. Additionally, Nakamatsu starts to experience auditory hallucinations, voices which at times assert themselves over our protagonist. His stream of consciousness takes a backseat as various Issei (first generation immigrants from Japan) take center stage. At times, Nakamatsu is reduced to no more than a vessel through which these ghosts recount.

Descending into madness, Nakamatsu begins dressing as one of his father’s old friends, Etsuko Untén. For Nakamatsu, Untén exists solely through dubious stories from his childhood, as well as a few old photographs (Untén had been held up as a hero during the Second World War, proudly embracing his Japanese heritage in the face of the violent discrimination the Japanese were facing in the Americas). Nakamatsu assembles an outfit based on Untén’s in an old photo: gray felt hat, dark canvas coat, tortoiseshell glasses, blue ties with pinstripes, narrow-legged trousers, and a wooden cane with reinforced handle. In his new threads, Nakamatsu also believes himself to resemble—embody, perhaps—his beloved Martin Adán. Literally and metaphorically reborn, we follow Nakamatsu’s aimless wanderings around working class neighborhoods in Lima, brushing shoulders with thugs and prostitutes. In contrast to his total passive acceptance in the face of death, this simple wardrobe change is significant. Is this Nakamatsu holding up two fingers to fate? If he is pushed toward his own death by this stoic ancestral resignation, why not escape himself in the process, amorphous and proud? Better yet, mightn’t he form a true self on the way out?

Lines can be drawn between Nakamatsu’s mimicry of his heroes and the plight of Japanese citizens in Peru. In Higa Oshiro’s own case, Japanese-Peruvians were often met with hatred on both sides (in 1990, when Oshiro returned to Japan, he experienced discrimination for being a foreigner). Thus, they lack the privilege to build a sense of self around the foundations of nationality: Nakamatsu is left to fend for himself, ultimately constructing a final identity that may ostensibly seem like simple imitation. Isolated, he sees Etsuko as emblematic of degrees of bravery that feel unattainable to himself. How might he express these feelings, if he feels that his ancestral roots don’t allow for such characters? Similarly, those feelings inspired in him by Martín Adán are unshareable; metaphysical thinking is an inherently lonely, abstract pursuit, forever butting heads with the practical world.

Does Etsuko reveal to Nakamatsu untrodden elements within himself? It might seem there is nothing authentic about this mimicry; Nakamatsu is only playing the role of somebody else to get away from his self-hatred. I, however, see this final choice, in contrast to his total resignation, as revealing and heroic: On his way out, Nakamatsu takes the chance to reinvent his sense of self, one that isn’t rooted in shame. A man without a country, he is unable to turn to his nations to pull a sense of self together. On his way out, Nakamatsu finds a sense of belonging in a sphere that is incapable of ostracization: fiction.