[drop-cap]

I watched the great Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman’s first feature, Je tu il elle (1974), for the first time on the same day that the first case of Covid-19 was confirmed in the United States. Two months later, with much of the world in lockdown, the first of the film’s three distinct sections especially resonated with me. In it, the 24-year-old Akerman (vaguely differentiated from herself in the mononymous end credit “Julie”) is alone in her room arranging and removing heavy furniture, writing a letter, undressing, dressing again, and ingesting from a paper bag some scientific bare minimum of sustenance: sugar by the spoon. More or less simultaneously, Akerman’s matter-of-fact first person, past tense voiceover describes her character’s actions, which she says span about 28 days of isolation. Far from being slow or tedious, it’s an arresting exercise of dramatic imagination in a confined space and constricted state of mind, with the determination of her movements and compositions overriding any need for narrative context. There are countless other resonances (sexual, political, artistic) and unshakable sequences over the remaining hour too, when she hitches a ride with a young trucker and spends the night with a lover. These include the trucker, in a single take, telling his twisted, melancholic life story in the grainy black of his truck cab, and then, in a brightly lit apartment, the long, sculptural love scene between Akerman and Claire Wauthion that famously ends the film.

With long haul travel and social visits of any kind off the table, there was something in those early, anxious homebound months of the pandemic that imitated the first solitary section of Je tu il elle. Your house, your apartment, your room, whatever, became all there was, and while gaining a new appreciation for having any roof at all over your head, it was against this setting that, like Akerman, you were suspended in a state of indeterminate pause, waiting and waiting. Joseph Beuys’ performance piece I Like America and America Likes Me, executed fittingly in the same year Akerman shot her film, also came to mind, although its premise of spending three days in an empty room with a coyote, while thrilling, was almost the opposite of staying indoors during a pandemic, when the danger is outside and propagated by human free will. Akerman’s other early films were fitting company too, where she demonstrated the artistic canvas she could make of a living space and the way that space could make captives of her living subjects. In Saute ma ville (1968), her very first film, she uses 10 minutes of confinement in a banlieu kitchen to build and blow up a scene of modern domesticity; in her most well-known, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), she extends that idea over 200 masterful minutes which cover three days in the life of a single mother. In between those are the structural films she made while living in New York (like 1972’s interior explorations La chambre and Hotel Monterey) and Je tu il elle.

Akerman’s other early films were fitting company too, where she demonstrated the artistic canvas she could make of a living space and the way that space could make captives of her living subjects.

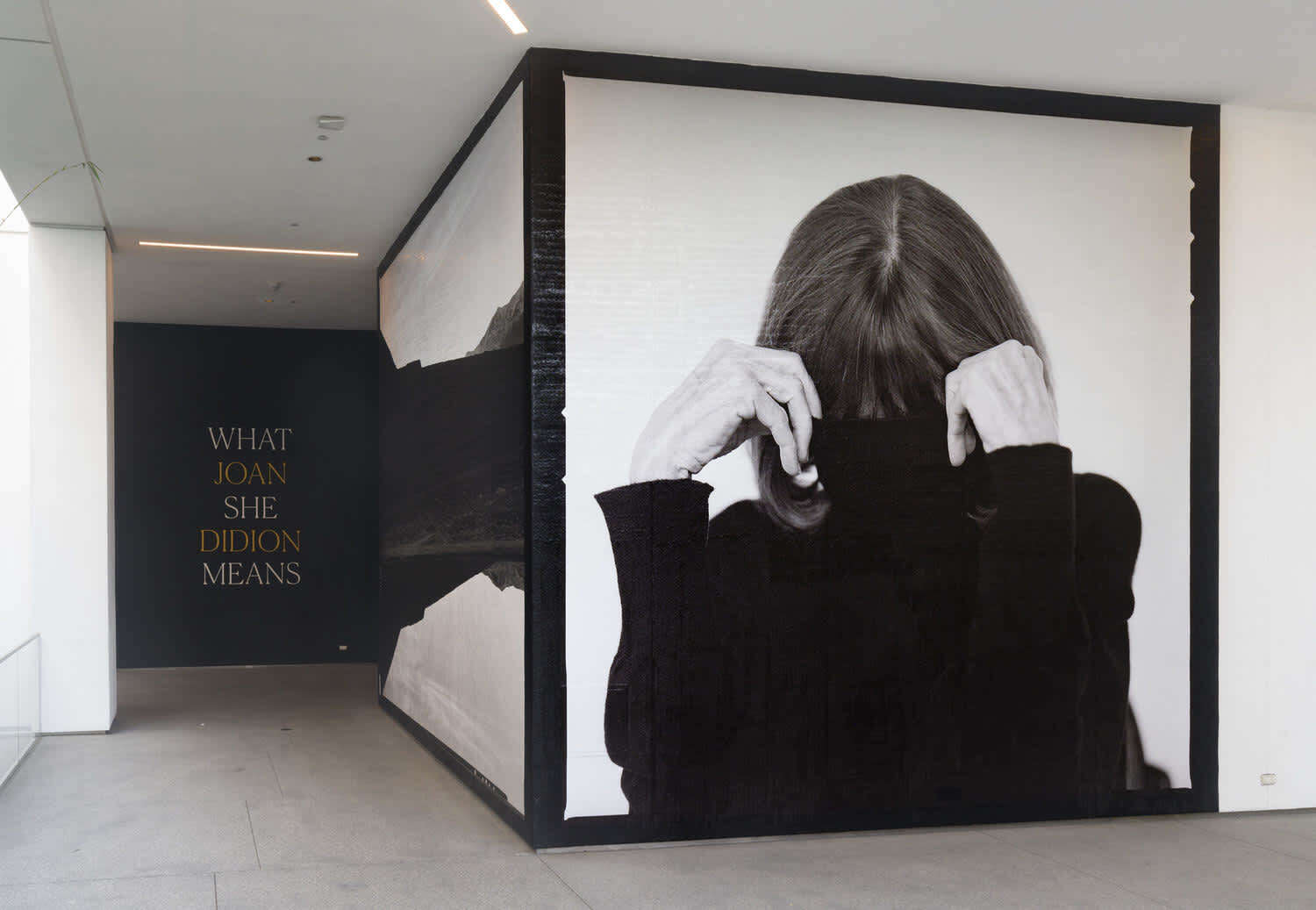

Then she turned 25. Over the next 40 years, the concerns of Akerman’s films expanded outwards from the foundations of her early films; in the very first place, News from Home (1977), the personal documentary that followed Jeanne Dielman, consists almost entirely of exterior shots of New York City and Akerman’s voiceover reading the letters she received there from her mother, a central source of inspiration in her life. Until her death in 2015, Akerman’s freedom as an image maker would allow commercial forays (1996’s A Couch in New York) alongside observational experiments in the aftermath of the USSR (1993’s D’Est) and, eventually, commissions from biennales and museums. Currently, the Marian Goodman Gallery in Paris is exhibiting two of Akerman’s rarely seen video installations that suggest yet a deeper significance in her work.

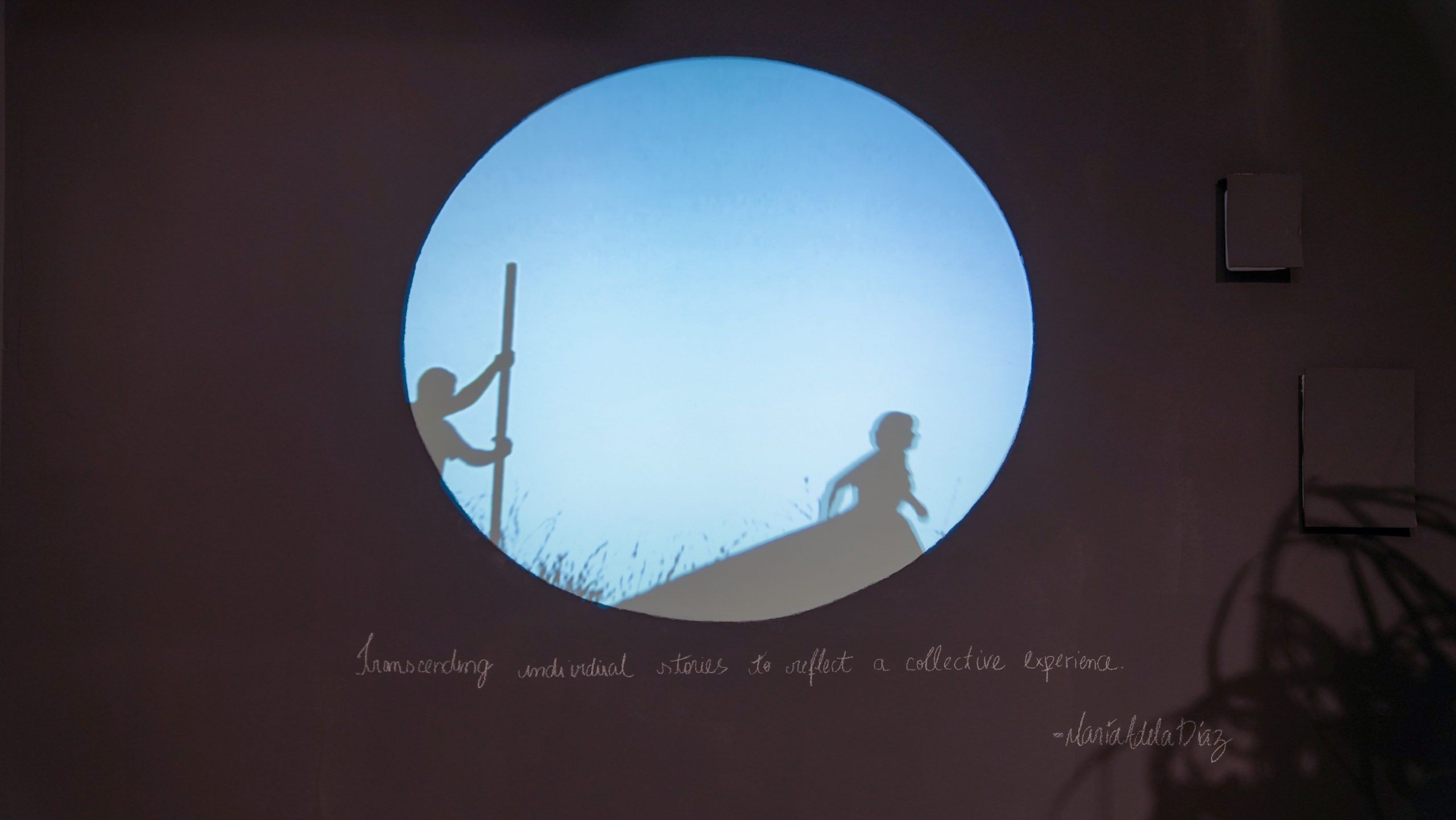

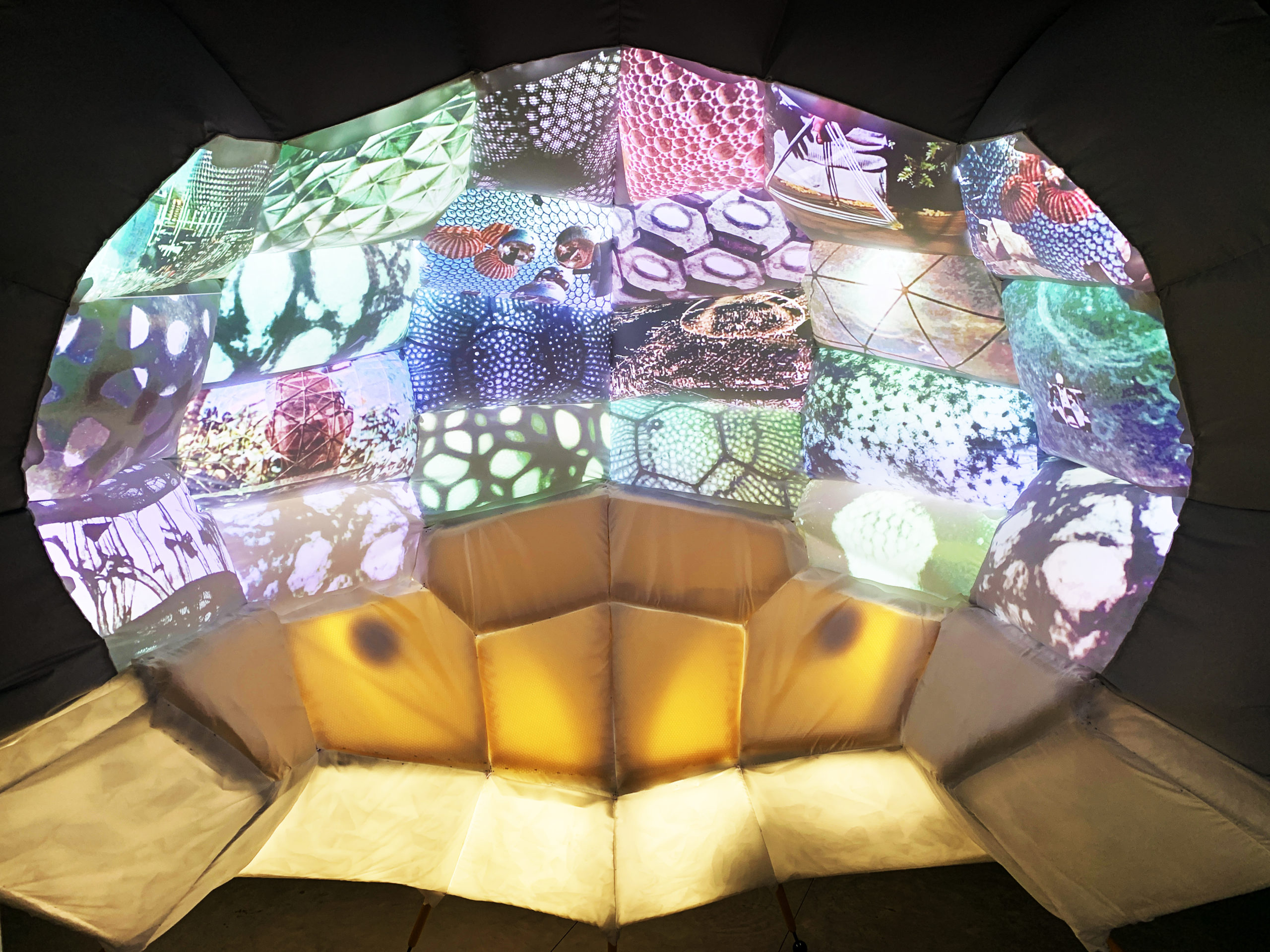

The first is Je tu il elle, l’installation (2007), in which excerpts from each of the 1975 film’s three parts (Akerman in her room, on the road, and with a lover) are shown side by side with the help of three projectors. The second installation, not exhibited in over a decade, is From the Other Side (2002), based on her documentary of the same name and year. A more radical restructuring of its companion film than Je tu il elle, l’installation, the piece spans three dark rooms and plays out on 20 screens. In the central room, you walk, like a Best Buy customer, among an array of 18 monitors arranged in rows on black, chest-high pedestals. The monitors play footage from the film, shot along the US-Mexico border, which captures with equal attention and effectiveness the borderland itself and the testimonies of the people living there—particularly those who’ve seen loved ones make or attempt the crossing north. Disturbing footage obtained from US border authorities after the film’s release also plays, showing migrants chased down in the middle of the night via cameras mounted on low-flying helicopters and ATVs.

It has been well argued that by scattering her cinema across multiple screens and giving viewers the choice of where to look, what to hear, and when to come and go, Akerman’s gallery installations put you in the driver’s seat (the director’s chair, even), liberating you from the sense that, by passing hours in front of her quieter, observational films, you’re whiling away “the time that leads toward death.” Factually, the installations are liberating along those lines by the simple token of their gallery setting, though I found, conversely, that they imparted all the more intensely the substance and themes of their film versions. In literally walking among her moving images and, alternatively, observing from a distance the visual threads of her films unspooled and juxtaposed in parallel, the cold structure of Je tu il elle is clarified as Akerman’s frantic passage from introspection to observation and, finally, connection. In the From the Other Side installation, the sorrow felt by separated families, visible through their fidgeting and their fragile composure, is felt more acutely when flanked directly by scenes of unflinching border fence and gray desert sunrise.

Altogether, the exhibition is as absorbing as seeing the original films on the big screen, and, with her work’s essential concern for overcoming alienation, it underlines the reward of encountering Akerman out in the world again.

Chantal Akerman, From the Other Side

Ran December 9th, 2021 — February 5th, 2022

Galerie Marian Goodman

79 rue du Temple

75003 Paris

Je tu il elle is available to stream on the Criterion Channel.

From the Other Side is available to stream on Amazon.