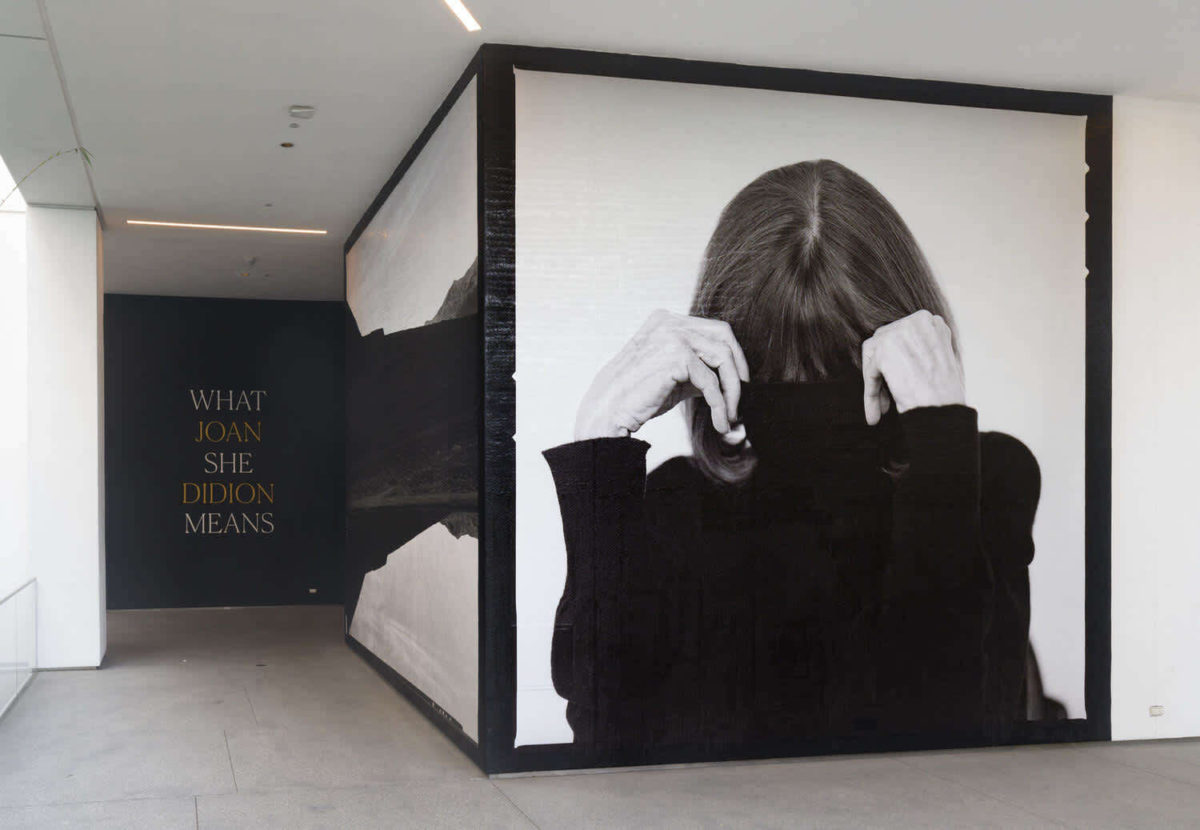

Joan Didion’s life and work at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

SILENCE IS POWER. In conversation, the persistent silence of one unsettles the other, driving the speaker to give more of themselves away as they grasp for a sense of their counterpart. In the case of Joan Didion, her slight frame and tightlipped aura made her both a disarming and formidable presence as a reporter. The woman who said, “I like to sit around and watch people do what they do,” was, after all, the writer that dubbed writing “a hostile act.” Writing, she suggested, was a performance in deception. But what worked so well for her in life—her cool, controlled approach to reflection and deflection—is taking on a curious afterlife. In her absence, we seem to be indulging our need to fill her many long silences with meaning, telling ourselves stories about Joan in order to live.

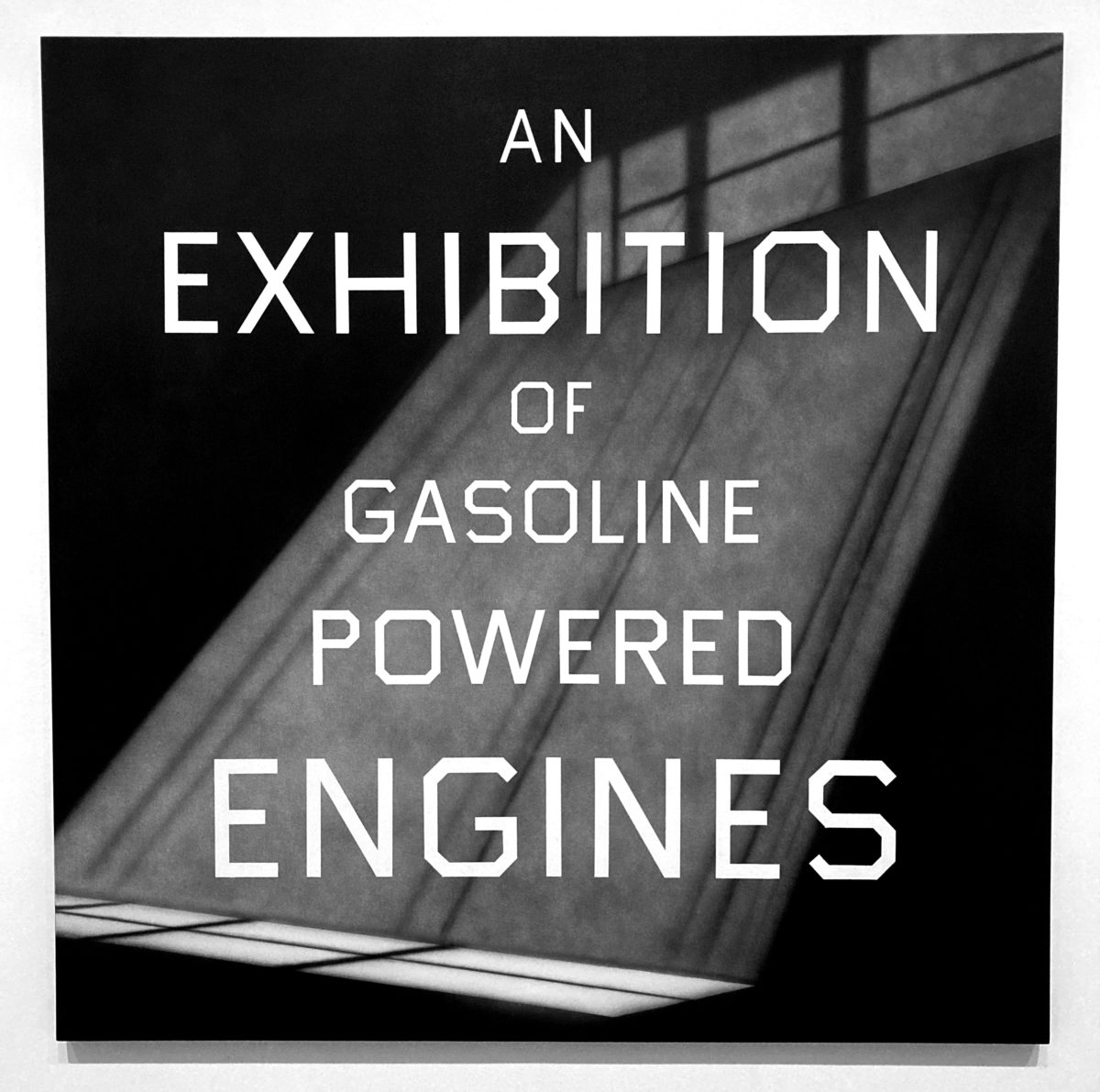

“Joan Didion: What She Means,” curated by New Yorker theater critic Hilton Als for the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, is one such tale. For Ann Philbin, the Hammer’s director, it is “an exhibition as portrait, a narrative of the life of one artist by another.” It is also a striking survey of the many nouns that make up a moment in time, a life. Featuring over 200 separate items—ranging from artworks by a wide range of mid-century artists including Wayne Thiebaud, Betye Saar, Richard Avedon and many more, to personal effects, ephemera, and mementos—the exhibition offers impressive glimpses of the landscape of postwar America, revealing just how close Didion got to the era’s defining cultural booms.

The exhibit is organized chronologically into four sections, named after her famous essays: Holy Water: Sacramento, Berkeley (1934-1956); Goodbye to All That: New York (1956-1963); The White Album: California, Hawai’i (1964-1988); and Sentimental Journeys: New York, Miami, San Salvador (1988-2021, despite the fact that both Salvador and Miami were published before 1988). Holy Water in particular furnishes the viewer with a sense of place, the landscape of extremes Didion was born into (Sacramento, 1934), made all the more urgent in our drought-ridden era. Speaking to Linda Kuehl for her first Paris Review interview in 1977, Didion reflected on her inheritance: “I grew up in a dangerous landscape. I think people are more affected than they know by landscapes and weather. Sacramento was a very extreme place… Those extremes affect the way you deal with the world. It so happens that if you’re a writer, the extremes show up.”

Maren Hassinger’s River runs through the center of Holy Water, a 7” x 89” x 358” mixed-media installation made of rope and steel anchor chain—imposing in its bulk and materiality—that, while originally evoking the chains and ropes of enslaved Africans through the Middle Passage, here doubles as an expression of California’s complicated relationship with water. Meanwhile, along one wall, Suzanne Jackson’s acrylic washes evoke Didion’s penchant for spare yet meticulous prose with vibrant yet muted violence. Als’s emphasis on a rich array of African American artists certainly enhances the show, though it speaks more to Als’s end of the dialog than Didion’s. While “Didion knew,” Als is convinced, “that America was built on exclusion: the exclusion of one class or race in favor of another,” Didion herself remained a bit more opaque on such interpretations of American history, her work built a bit more upon investigations of exclusivity.

Opportunities to “spot the Joanie” abound through yearbooks and school photos, before making way to an altar to some of her literary influences: e.g. Ernest Hemingway, Graham Greene, and Norman Mailer. It’s always striking to note how Didion counterbalanced her fragile physical presence, even her femininity, with prose that was so informed by some of the most forcefully masculine figures of 20th century literature. “Novels by women tended to be described… as sensitive,” she told Kuehl, “and I didn’t much like it.”

While the artworks throughout are both contemporaneous and thoughtful evocations or complements to Didion’s work, few are as striking as Vija Celmins’s Gun With Hand #1 (1964). Showing an outstretched arm clutching a freshly fired .38 revolver amid a landscape of dusty nothingness, Gun With Hand captures the tone that pervades so much of Didion’s musings on California, especially “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” the opening essay from Slouching Towards Bethlehem. “This is a story about love and death in the golden land,” the essay opens, “and begins with the country.… It is the season of suicide and divorce and prickly dread, wherever the wind blows.”

By the time we get to The White Album (1964-1988), the experience pivots to Joan Didion’s entry into history, a doubling of sorts where she is traversing time as a historical actor, her work and her ephemera history itself. Dividing the mid-1960s from the boom period of Didion’s cultural centrality that would follow is “Reel 77 of Four Stars,” a segment depicting waves crashing along the Malibu Coast from Andy Warhol’s 25-hour 1967 avant-garde film, projected floor to ceiling onto a partition while Nico’s ever-haunting voice induces a kind of conscious “drifting.” Between 1965 and 1972 alone, Joan—along with her husband John Gregory Dunne (himself an essential witness through his works Delano, The Studio, and Vegas)—“consciously drifted” into (and reported on) tectonic shifts in the social order of California including Haight-Ashbury, Cesar Chavez and the California Grape strike, the Manson Murders and subsequent trial, the Black Panthers, the slow but steady rise of Las Vegas as an outpost of the western id, and New Hollywood’s ushering in of film culture as epicenter of American intellectual discourse.

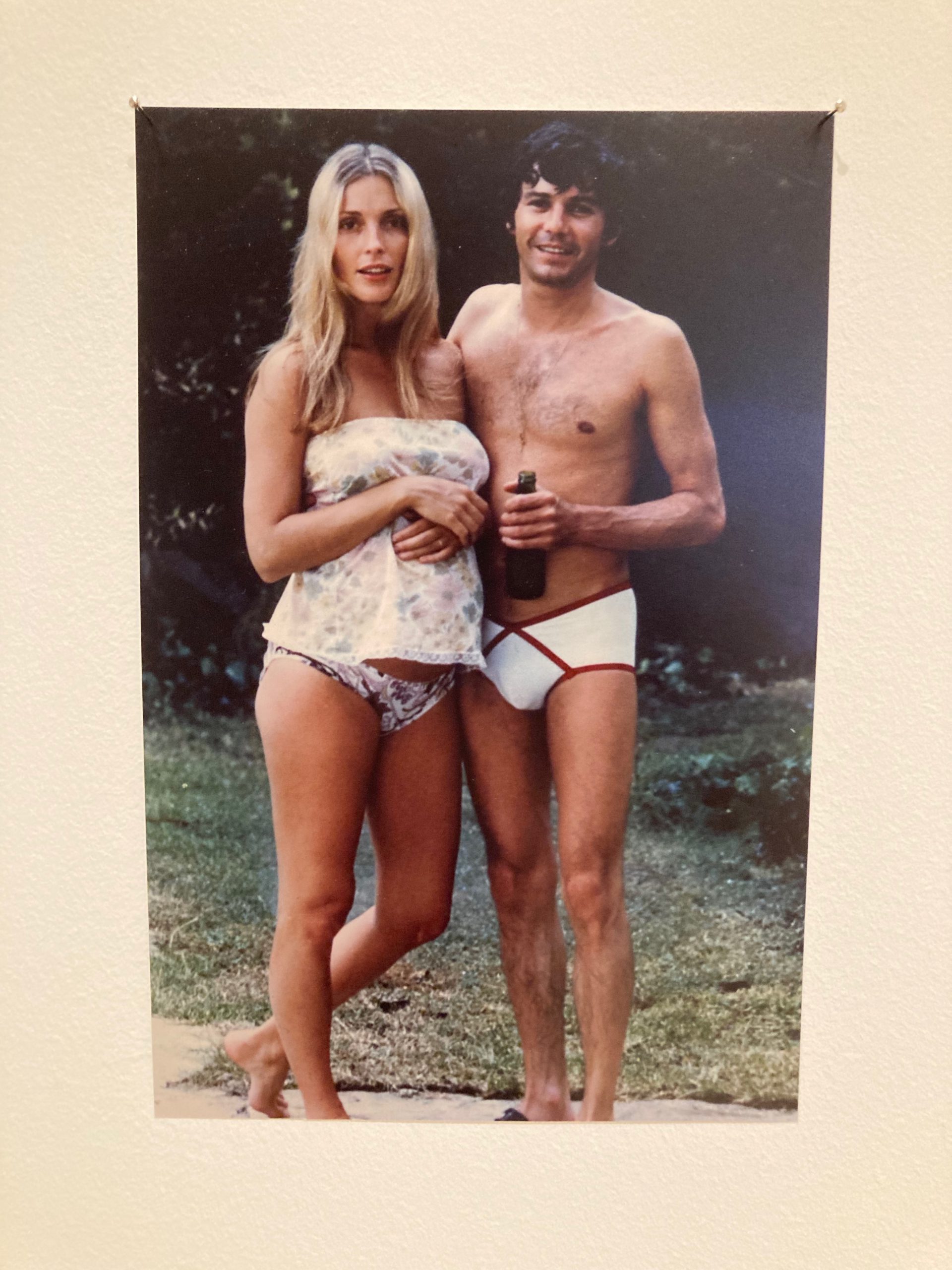

Surrounded by the overwhelming materiality of postwar American culture—a period so relentlessly documented and commodified—it’s deeply impressive to think Didion lived through it all, observed it all, and commented on it all from behind her dark sunglasses and Hermes typewriter. Of course, for Didion, “it was gold” (as she said notoriously of the little girl she saw on LSD in “Slouching”). The exhibition’s strength lies in allowing you an opportunity to feel the period for yourself (you rarely have to read the didactics because so much of what’s displayed speaks for itself). How does it feel to look at five seemingly random Polaroids—until it hits you in the gut there’s absolutely nothing random about them—of pregnant Sharon Tate lounging around poolside, sometimes alone, sometimes beside Jay Sebring? Sometimes, it feels as though history is largely a collection of mishaps fated to irremediable consequence, indeed “the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images,” as Didion suggested in “The White Album.”

The exhibit closes, somewhat lacklusterly, with Sentimental Journeys (1988-2001), the era of “Saint Joan.” Ana Mendieta’s Untitled: Silueta Series is a highlight, a haunting collection of abstract black and white photographs which Mendieta hoped would express “an omnipresent female force.” What’s clear, however, is the aura of dormancy that seemed to categorize Didion’s later years, with the exception of her two momentous losses, as though a great ship had been retired from service. There is little added weight to enrich some of the sojourns and involvements Didion embarked on during this period, although a look at the Central Park 5 is an integral highlight. Joan Didion has captivated a strikingly wide array of people, but this latter New York period does make you wonder what it meant to the Californian to be New York’s go-to Californian, particularly in an exhibition curated by a New Yorker.

Didion’s California exists exquisitely in her pages. For anyone passionate about those pages, the passion will continue. But for those more ambivalent about her cultural anointment as Saint Joan of the Golden State, ambivalences will remain. Didion said “being left alone and leaving others alone is regarded by members of my family as the highest form of human endeavor.” The nature of her work clearly refuted that, as have the circumstances following her death. Nevertheless, the mystery at the core of Joan Didion remains.

Despite the show’s “meandering chronology that grapples with the simultaneously personal and distant evolution of Didion’s voice as a writer,” we come no closer to determining which Joan— “Saint Joan” or “Fragile Joan, Mother of Sorrows” or “Cool Joan, Angel of Death”—fits best. Likely, it’s all three and more. Her work is her testament; her life amounts for less despite our unfaltering need to turn such murk into meaning. And Als’s show is a tableau haunted by the ghostly presence of a careful observer, one who followed the currents but resisted its sometimes destructive allure. “A certain amount of resistance is good for anybody,” Didion said. “It keeps you awake.”

“Joan Didion: What She Means”

The Hammer Museum at UCLA

10899 Wilshire Blvd

Los Angeles, CA 90024

11 October 2022 – 19 February 2023