The French Dispatch and Returning to Reims (Fragments)

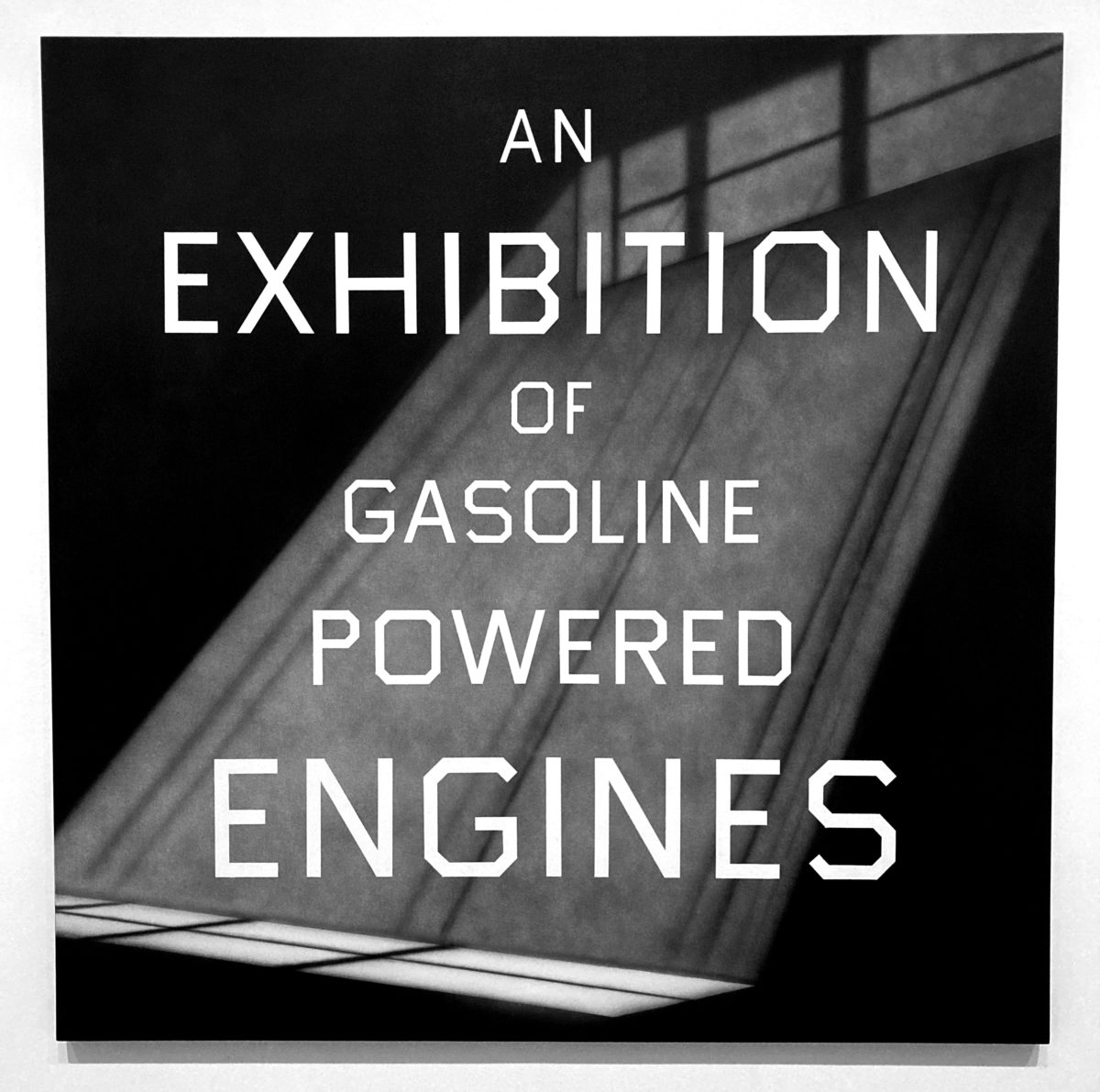

The first few frames of Wes Anderson’s new film, The French Dispatch, show an unpeopled printing plant in action, with handsome cast iron machines ushering leaves of paper here and there across an airy factory to the rhythm of a locomotive-like Foley track. We are looking at a miniature model, one of Anderson’s calling cards, and it appears just long enough for production company credits to flash overtop, opening this intricately crafted and frantically paced period-piece fiction which profiles a staff of American expat writers and the midcentury France they fashioned for the benefit of their readership back home in Liberty, Kansas. The film is presented as distinct episodes in which “factual” articles of Anderson’s creation (about the magazine’s late editor, its homebase in France, a jailed painter, a student protest, and a kidnapping) are brought to life, with the equally fictitious author of each one leading us through their work.

Jean-Gabriel Périot’s Returning to Reims (Fragments), which, like The French Dispatch, first appeared at last summer’s Cannes Film Festival, also constructs a version of France over the last century or so, with the sort of workers who are absent from Anderson’s printing plant making up the focus of Périot’s film. In it, excerpts (the title’s “fragments”) of the left sociologist Didier Eribon’s landmark 2009 book Returning to Reims are read in voice over and complemented by a masterful archival assemblage of classic film, agitprop reportage, and shaky firsthand footage to convincingly construct a telling of modern French history in which the miserable conditions of French workers and their political subjugation defy the country’s mythic charms.

The French Dispatch is playing in theaters worldwide and will be seen by millions, while, as of this writing, Reims (Fragments) will only have a limited domestic release in March 2022, though it might end up on a cinephile streaming service. The silver lining is that Eribon’s original book is readily available in an immensely readable English translation from MIT Press.

It is a testament to Anderson’s art that The French Dispatch, in its concern with the observing intellectual’s interpretation of the world around her, laced with parentheticals and sudden shifts in time and place, has more in common with the form of Eribon’s self-inquisitive social analysis of post-war France than its film adaptation. But Anderson also creates that very world into which he sends the likes of Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) and J.K.L Berenson (Tilda Swinton), and in doing so he draws from the same fount of canonical French cinema that Périot does when he slices and dices scenes of Jean Renoir, Jean Vigo, Chris Marker, Jean-Luc Godard, and others to illustrate Eribon’s trenchant reflections on working class identity and power. Périot pairs Eribon’s account of his family moving from a single furnished room in town to a new concrete housing development with segments from Marker and Pierre Lhomme’s verité documentary Le Joli Mai, an epic on the ground survey of an antsy France in the early 1960s. They document the mix of excitement, dread, and uncertainty surrounding the national transition that Eribon writes about personally, along with the degraded living conditions that preceded it. In The French Dispatch, an unromantic tour around town from Wilson’s Sazerac leads us through the same socio-spatial evolution, including a miniature model reference to the demolition of Paris’ Napoleon III-era food market for the Westfield Mall that stands today in its place.

Eribon’s book is also a memoir of growing up gay and intellectually-inclined in a particular working class milieu that vehemently despised these traits (a thread less explored in Périot’s film) and in the book’s epilogue, he writes about the importance of cultural references for fusing his personal experience and political analysis of the France that raised him:

I understood that a project like this…could only succeed if it was mediated by, or perhaps filtered through, a wide set of cultural references: literary, theoretical, political, and so on. Such references help push your thinking along, they help you formulate what you have to say. But most importantly, they permit you to neutralize the emotional charge that might otherwise be too strong if you had to confront the ‘real’ without the help of an intervening screen.

Indeed Eribon in his book, like Périot in his film adaptation, wields like a flashlight myriad signifying references, be they cultural, as stated, or sensory or material, to light a path from the local to the universal. Anderson has done much the same in his 10 feature films, and never so mesmerizingly as in The French Dispatch. Uncannily, Eribon above lays out a fine formulation of the chief characteristic of Anderson’s style (a message mediated through exacting visual reference), followed by the common criticism that his style serves “to neutralize the emotional charge” of the message. But Eribon presents that effect as the intended outcome; emotions without a referential intermediary “might otherwise be too strong.”

Is this where the chance utility of Eribon’s passage for understanding Anderson’s bewildering craft finds its limit? On the contrary, it is additionally useful: the “intervening screen” of his artistry, which stands between us and the stories his characters act out, neutralizes the force of facile (strong, or blunt) sentiments that other contemporary filmmakers of his renown aim at. Instead, Anderson’s visual style disorients traditional emotional dependencies in cinema, which can muddle our initial reception of his, but ultimately makes for a lasting attachment to the images that make it up: red tracksuits evincing fatherly love and neurosis in equal measure (The Royal Tenenbaums), fanciful pastries securing passage by prison guards and fascists (The Grand Budapest Hotel), or most recently, an assault of printed matter (maps, letters, manuscripts) flatly containing as much dynamism as the action to which it is apparently incidental.

If filmmaking is a technical process that makes an emotional impact, politics is an emotional process that makes a technical impact. The politician’s campaign appeals to our intractable attitudes about the world around us while his term in office lets him tinker with the tangible, whether the environment, borders, or the populace’s welfare and safety. Reims (Fragments) emphasizes that the politicians of the French Left gradually abdicated their responsibility to synthesize and marshal the innate hope and despair of the oppressed and exploited. Instead they became enamored with technical reforms and theories of change that saw class identity as a friction to the proper functioning of modern society—or irrelevant at best. In the meantime, the nativist right sold a simple story that immigration was to blame for all that ailed the French worker, and soon private prejudices coalesced under slogans like “Two million unemployed is two million immigrants too many!” This was in the late 1970s, a decade after “French workers, immigrant workers, same boss, same struggle” was one rallying cry of the May 68 movement.

If filmmaking is a technical process that makes an emotional impact, politics is an emotional process that makes a technical impact.

Anderson pays homage in his way to May 68, centering an episode of The French Dispatch on besuited students who kickstart a protest movement with partly carnal motivations and face off against authority over chess matches, all under the slogan “The children are grumpy.” In the historical analogue, their idealistic, hormonally spontaneous actions would be matched by a general strike of millions of French workers. Unlike the film’s other sections, this one, titled “Revisions to a Manifesto,” does not document a freshly crafted fiction as much as it leans on a popular, certainly picturesque, but ultimately omissive narrative of a historic event. It does succeed on one level as an ode to Mavis Gallant’s telegraphic reporting on the protests in The New Yorker, with Frances McDormand convincingly infusing the terse glances, gestures, and actions of her Lucinda Krementz, covering the story, with a mixed-up air of skepticism and overriding admiration. Yet little she witnesses hints at the era’s fascinating and fraught interplay of student, worker, and authority interests any more thoughtfully than a distressing 2018 Gucci ad campaign exploiting the movement’s 50th anniversary. In the past, Anderson has been capable of richly transposing even the darkest days of history, but here, giving himself a scant 25 minutes to work with, he opts to print the legend, now that the fashions surrounding it carry as much weight as the facts that came before.

As told in the film’s first few minutes, The French Dispatch folded in 1975 following the death of its editor Arthur Howitzer, Jr, (Bill Murray). Could it have continued much longer otherwise, with world-shrinking tools like television and the internet in the offing, threatening to render it all redundant anyway? The startlingly humanist conclusion to the final, and supreme, episode of The French Dispatch brings a Black gay journalist in Jeffrey Wright’s Roebuck Wright to the sickbed of an immigrant chef by the name of Nescaffier (Steve Park) and suggests the answer is yes. Or rather, it suggests that the yearning and othering that send some far away from home, that incite inquiries into the capital-F Foreign, is not necessarily to be conquered, but rather fostered into an open, sympathetic slant on the world, one that will exist above and beyond its occasional articulation in letters home or columns of a thin magazine.

And would the forces of globalization, some of which also trivialized the tradition of dispatch journalism, have further marginalized the oppressed in France, even absent the institutional Left’s capitulation and the opportunism of a despicable right wing revealed in Reims (Fragments)? Périot emphasizes the political failure that hides behind vague structural excuses when he concludes his film with a rousing crosscut of firsthand footage from the many progressive movements that march in towns and cities across France today. The sequence accelerates into an ecstatic cacophony of agitation and a cunning update of Eribon’s analysis: The people are all right, even in the face of an authoritarian swing at home and abroad—they’re only deprived of a deft hand to mesh their messages, an honest editor-in-chief to shrink the masthead and make space for the mundane and monumental alike.

The French Dispatch

Wes Anderson

107’, 2021, USA/Germany

(Now playing in theaters)

Returning to Reims (Fragments)

Jean-Gabriel Périot

83’, 2021, France

(French Release March 2022)