Editor's Note: As part of the WPA, the Federal Arts Project was terminated in 1943, after several years in which its range and funding had languished. Mostly between 1935 and 1939, the artists of the FAP created 108,099 easel paintings and 17,774 pieces ofsculpture. In New York and elsewhere, a selection of these works was exhibited in museums, community centers, art galleries, union halls, and, most often schools, in connection with the project’s art education programs. As the project was wound down and closed down during the war, the vast majority of the artworks were warehoused and subsequently discarded—auctioned off as junk or simply scrapped. The documentation of their “allocation” was lost. For more on the history andsignificance of the WPA /FAP, see Bram Dijkstra, American Expressionism: Art and Social Change l920-1950 (2003); included is an illuminating reference to a story in Life magazine, April 17, 1944, headlined “End of WPA Art: Canvases which cost government $35,000,000 are sold for junk,” and reflective of Life’s prejudice that the New Deal arts projects had been a boondoggle; it is now available online. Other accounts of the project can be found in Francis V. O’Connor, Federal Support for the Visual Arts: The New Deal and Now (1969), Robert D. McKinzie, The New Deal for Artists (1973), Andrew Hemingway, Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926-1956; Robert G. Kennedy, When Art: The New Deal, Art, and Democracy (2009). McKinzie also provides aconcise account of the Federal Art Project in Franklin D. Roosevelt: His Life and Times: An Encyclopedic View, ed. Otis L. Graham, Jr. and Meghan Robinson Wander (1985).

[drop-cap]

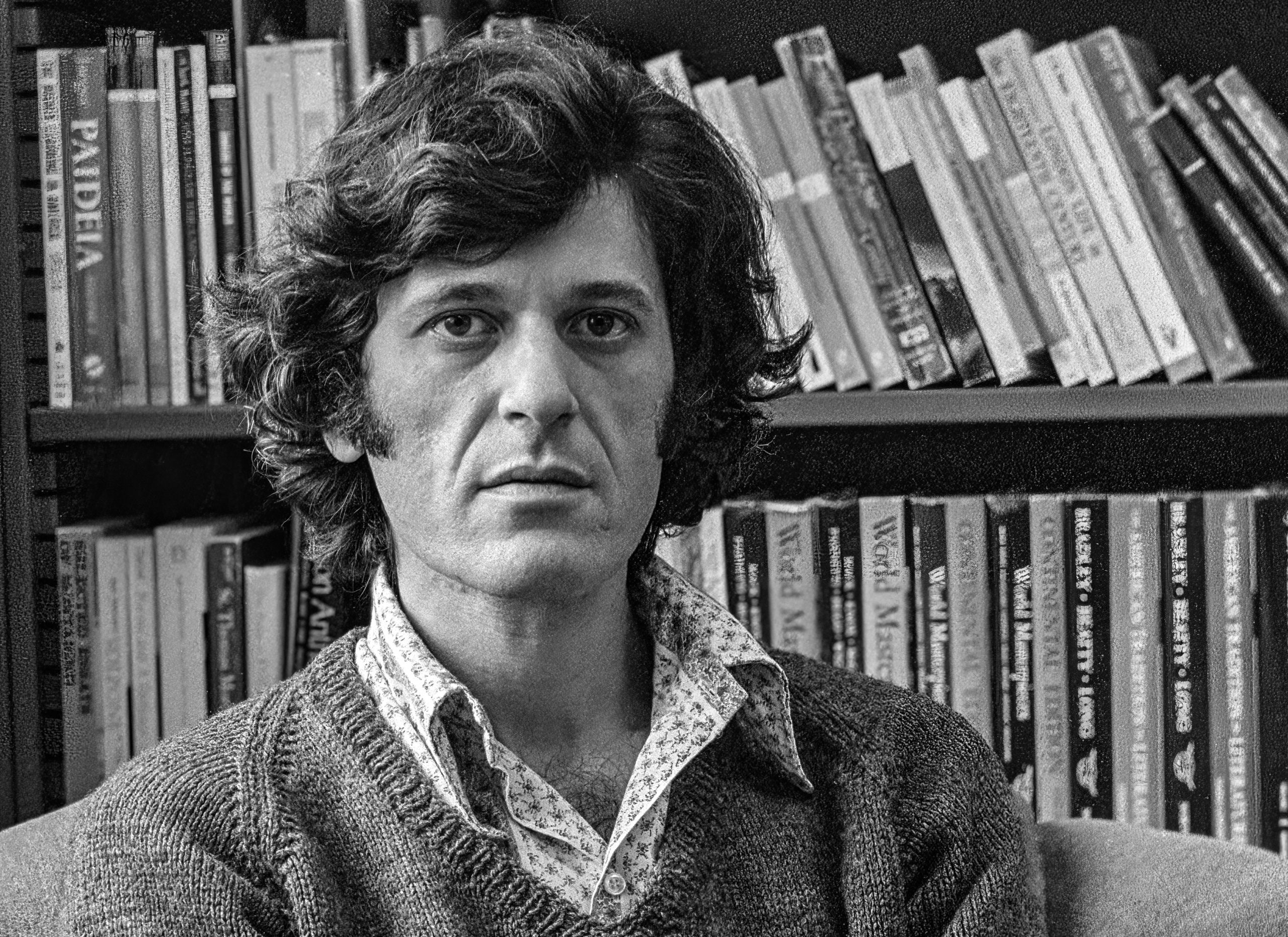

In lists of the most influential American artists of the past century—Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol, Georgia O’Keeffe, etc.—one name is sure to be missing: George Biddle. For exercising perhaps the most widespread (if improbable) impact on American art during a critical moment in its history, he should be equally renowned.

A member of the esteemed Biddle family of Philadelphia, George Biddle attended the Groton school in Massachusetts before graduating from Harvard Law School in 1911, after which he abruptly pivoted to fine art. Fueled by passion for his newfound calling and supported by his family’s wealth, he received formal training abroad in Paris and back home in Pennsylvania. After enlisting in the United States Army during the First World War, Biddle then embarked on a meandering grand tour through Spain, France, Tahiti, and elsewhere, copying the old masters and trying on various stylistic hats wherever he went. A sketching trip through Mexico in 1928, alongside the famed muralist and communist Diego Rivera, proved particularly instructive. Rivera’s integration of artistic and social ambitions through large scale mural paintings sparked a similar desire in Biddle, who likewise sought to synthesize his artistic pursuits, legal training, and public service. When he returned home, he dedicated himself to public murals and lithography, alongside oil painting, in an effort to produce art of broader social purpose.

Biddle’s travels and social conscience appear hand in hand with his creative output. Tenderly rendered depictions of villagers in India, destitute American migrants, beggars in Mexico, and American soldiers on the front lines collectively attest to his civic responsibility, artistic development, and extensive resources. Yet, Biddle might have worked in obscurity if not for his connections. As fate would have it, Biddle’s childhood friend at Groton was a boy by the name of Franklin Roosevelt, who was elected president not long after Biddle wrapped up his time alongside Rivera. Inspired by the ideas connecting labor and art that he developed on his travels in Mexico, and having heard of plans for a so-called “New Deal” in the United States, Biddle wrote his longtime friend and now-president a letter, suggesting that some help for artists be provided in the form of government sponsored commissions. More precisely, artists could be employed to “capture America,” in ways reminiscent of Biddle’s own artistic ambitions, using their talents to adorn public spaces and buildings as had already been done successfully in other countries. Roosevelt agreed, and the rest is history.

The format of the resulting government program, under the umbrella of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Federal Art Project (FAP), belies the immense impact it had on the lives of artists throughout the United States. At the peak of the program, 10,000 artists received guaranteed income in exchange for completed artworks or time spent on public commissions. This resulted in approximately 100,000 easel paintings, 2,500 murals, 18,000 sculptures, 300,000 prints, and an immeasurable number of craft objects and posters from the federal government’s $35,000,000 investment (translating to $770,000,000 in today’s money). With that kind of public investment in the arts, it’s no wonder New York City, home to countless former WPA/FAP artists (Pollock included), soon became the epicenter of an increasingly global art community in the 1940s. Yet perhaps more significant than the overall impact on the art world—and certainly more overlooked—is the influence the program had on the lives of America’s perennially disregarded creative community: immigrants, women, Black artists, and others who were now seen by the government as essential workers serving a significant civic purpose and deserving of guaranteed income in exchange for their creative labor.

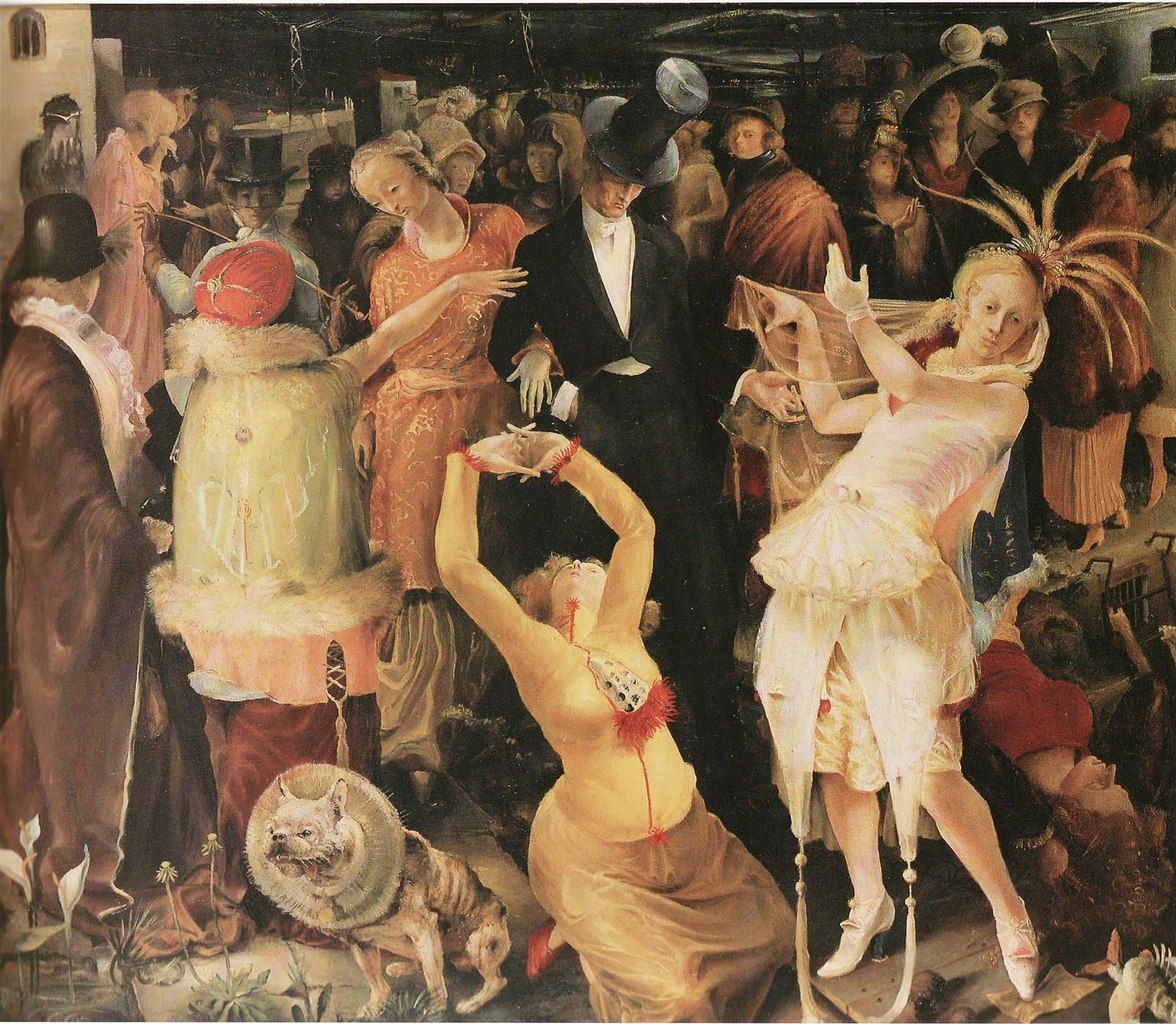

In today’s world, it is all too easy to romanticize these interwar programs as an alternative, more inclusive model of artistic production outside the hegemony of the commercial market. It is also easy to dismiss the art funded by these programs as naive, propagandistic, and sometimes overly illustrative of “American ideals” à la Norman Rockwell. Though neither view is entirely false, the reality is more complex. Review panels, public comment, and administrative procedures no doubt influenced the content of the large-scale murals and public sculpture produced under these programs. However, the easel paintings and smaller-scale sculptures sponsored by the WPA/FAP eluded much of the bureaucratic red tape; they could simply be rejected for public display. Arguably, the smaller-scale works produced under these programs more readily attest to the uncensored feelings of their creators, tasked as they were with capturing a nation amid the dust bowl, the Great Depression, and two world wars.

That certainly seems to be the case in Art for the People: WPA Era Paintings from the Dijkstra Collection, a refreshingly diverse exhibition of tender, emotionally wrought, and sometimes nightmarish oil paintings and sculptures produced in the United States between the 1920s and ‘40s, now on display at the Huntington Library in San Marino. Intimate in scope and drawn entirely from the private collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra, the show proposes a reevaluation of this often overlooked period of American art, all too often dismissed as a precursor to the innovations of Abstract Expressionism or a historical aside to F.D.R.’s New Deal. In contrast, Art for the People showcases a unique period in American art history where the typical relations between artists, patrons, and civic responsibility were momentarily altered in ways seemingly impossible to imagine today. To paraphrase Lincoln, to see this exhibition is to experience an art of and by the people, not just for them.

Art for the People proves timely in other ways. In many of the paintings, vivid psychological landscapes of gnarled hillsides, leafless trees, barren industrial wastelands, and gray skies—under which forlorn, isolated figures toil or ponder the changes around them—speak to today’s climate emergency, social inequality, and so-called “deaths of despair.” Take Fletcher Martin’s Migrant Woman (1938), wherein a woman sits on the ground along a riverbank, cradling her head with an elbow on her knee. Though the figure is still, her eyes and facial features are blurred and the fabric of her dress below the knees is marked with mud, mirroring the empty landscape around her and suggesting the toil of a long day. With a desaturated palette and loose brushwork, Martin captures a moment of recognition, introspection, anxiety, and grief, where migrant fantasies of the “American Dream” met political, social, and economic realities in a nation often hostile to their presence. The universality of Martin’s image—mirroring those coming out of today’s curbside migrant camps in New York City and refugee camps in Gaza—owes much to his restraint.

In other paintings, similarly isolated figures appear even more deprived and contorted, likewise faceless or turned away, often missing clothing, and sometimes buried in the earth. In Anton Refregier’s Plowed Under (1936), an otherwise pastoral landscape becomes a vortex of human suffering. Bent trees and pierced farmhouses twist around a large pit in the bottom half of the canvas, where a barefooted figure in overalls lies in cover, or death, amidst broken boards, discarded wheels, and other debris. Simultaneously depicting a bomb crater, grave, or trench, the painting could manifest as a harbinger of horrors to come or a final resting place in an otherwise destroyed world.

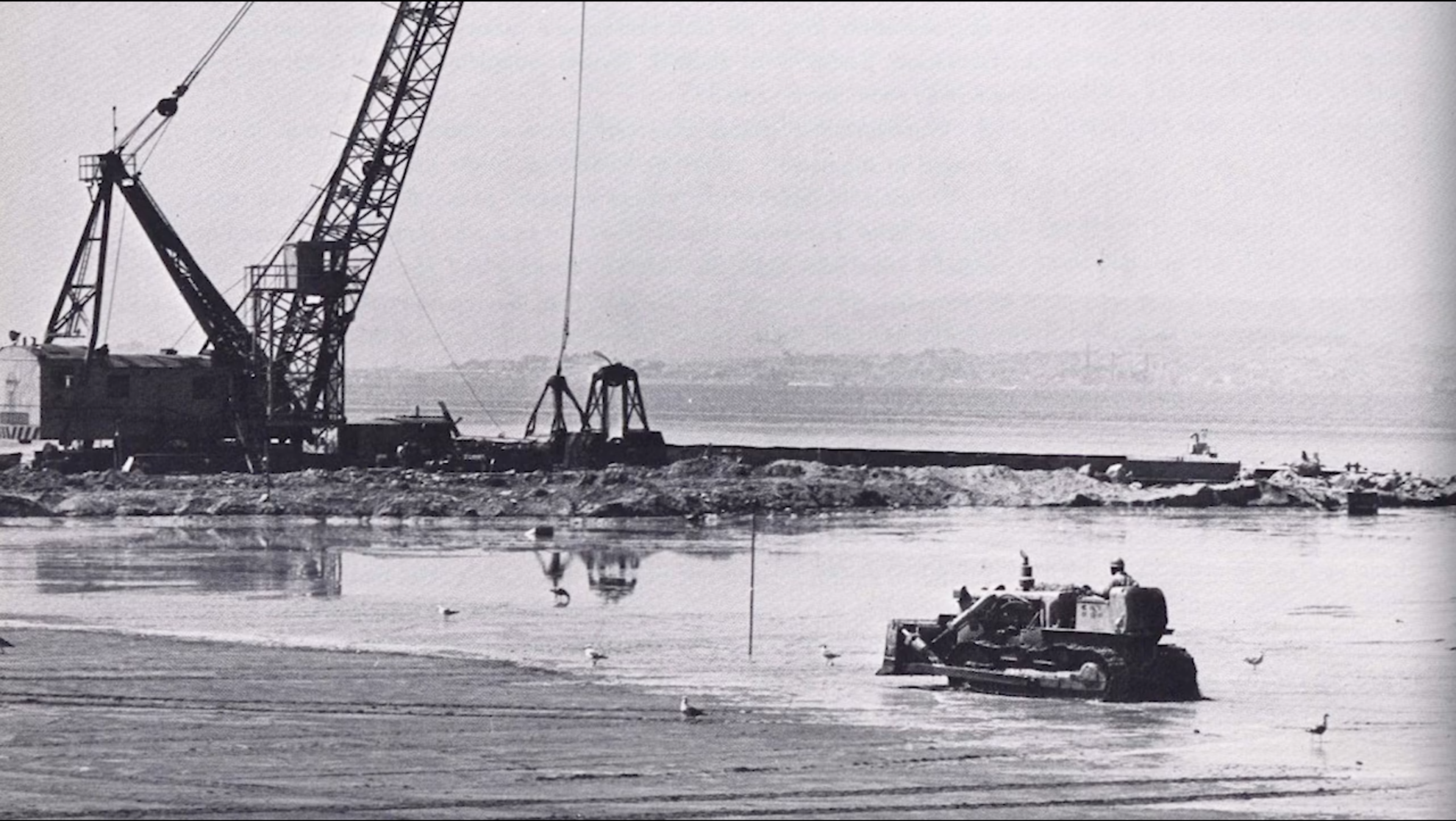

Landscapes like these make up the bulk of Art for the People, attesting as much to the show’s curation and the Dijkstra’s collection as to the social atmosphere of interwar America. Yet the common format never feels overwhelmingly thematic, and it makes the stylistic differences between artists more apparent. Nowhere does this strategy seem more intentional than in Arnold Blanch’s Rondout Creek (1932) and Earle Loran’s San Francisco Docks with Alcatraz Island (1940), both of which present industrialized waterfront landscapes along the east and west coasts. Hung side by side at the show’s earlier exhibition at the Oceanside Museum of Art, the paintings respectively highlight the changing landscapes and artistic developments of opposite ends of the United States. Blanch depicts a riverside factory complex where the only signs of life are gray plumes of exhaust, under which crumbling masonry walls, curved railroad tracks, and a dirty gray-blue sky are rendered with dabbled brushwork and a muted palette. Loran’s urban landscape is likewise devoid of people—save for a few cars, a cargo ship, and a Matissean nude on a billboard in the foreground—yet it is rendered in a much more graphic if vibrant style, abounding with green and red gables echoing the rocky coast of Alcatraz and the hilly San Francisco Bay beyond.

Art for the People showcases a unique period in American art history where the typical relations between artists, patrons, and civic responsibility were momentarily altered in ways seemingly impossible to imagine today. To paraphrase Lincoln, to see this exhibition is to experience an art of and by the people, not just for them.

Despite the commonalities and differences, the most surprising works in the show break away from these psychological and politically charged landscapes, appearing to stem from more personal and quotidian experiences. Images of a naked woman inspecting her toenails in a bathroom, a girl in a red sweater sitting on a chair, and a vase of pink peonies on a kitchen table more directly attest to the lives of their creators through the intimacy of their subject matter. At the very least, they offer respite from the show’s bleak depictions of interwar America.

The most powerful works in the exhibition appear to circumvent both trends. Case in point is Soldier, painted by Charles White in 1944 right after he was drafted into the US Army at age 26. With its subject looking upward, clutching a rifle like a security blanket against an ominous sky and placeless landscape, Soldier is a far cry from popular depictions of wartime camaraderie and heroism. By contrast, White’s painting attests to war’s loneliness, particularly for a Black man serving in a segregated military for a nation yet to experience the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. Adding to the drama is White’s ability to incorporate a wide range of reds, blues, yellows, and greens into all aspects of the painting through long, linear strokes, imbuing Soldier with a disorienting effect when viewed up close.

Here and throughout Art for the People, nothing about the WPA/FAP’s simple prompt for artists to “capture America'' seems to anticipate the power and range of the resulting artworks. The paintings and sculpture presented here are raw, intimate, and direct, capturing the suffering of the interwar years in unfiltered yet sophisticated terms. That such works are continually absent in art historical surveys is yet another reason why Art for the People is a refreshing if not incomplete project.

At the same time, I would argue that Art for the People offers a broader and more pertinent message stemming from George Biddle’s example. When privilege is shared and used to uplift those without, space is granted to make room for others; when public exposure and funding is offered to a diverse population of artists through institutional support, the art will find its own unanticipated uses. In short, the exhibition forces us to reevaluate the structures by and for which art is produced, displayed, and disseminated—and to accept that reality as an integral part of all works of art. Just as the influence of the Church cannot be separated from the art of the Italian Renaissance, it is difficult to separate the artworks in Art for the People from inclusive government initiatives in support of the arts, and from the Dijkstra collection and curatorial initiatives. Most of all, these artworks can’t be separated from the diversity and confidence of the artists, who flourished beyond the demands of the WPA/FAP to capture the pain, struggle, and beauty of a perennially evolving nation.

Art for the People: WPA-Era Paintings from the Dijkstra Collection

Ran December 2nd, 2023 to March 18th, 2024

The Huntington Library, Art Museum & Gardens

1151 Oxford Road

San Marino, CA, 911087

Catalog of the exhibition, with essays by Henry Adams and Susan M. Andersen, and introduction by Scott A. Shields, available at:

Crocker Art Museum, Oceanside Museum of Art, the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

64 pp., $24.95