[drop-cap]

Imagine a man in a stable marriage. He loves his wife, he works hard. But his wife works hard too—she’s got her own job, she keeps house, takes care of the kids. He needs a little nightly affirmation; sexual, sure, but also things like “You’re absolutely right, you’re a great guy, I appreciate you”—all the things he’d like his wife to say but can’t be relied upon to because she’s too exhausted to lie. So he turns to his “artificial intimacy avatar,” a friction-free solution to a desperate human problem, funded by his friendly, zero-liability tech firm who mines for profit all the sweet nothings and naked somethings of his every interaction.

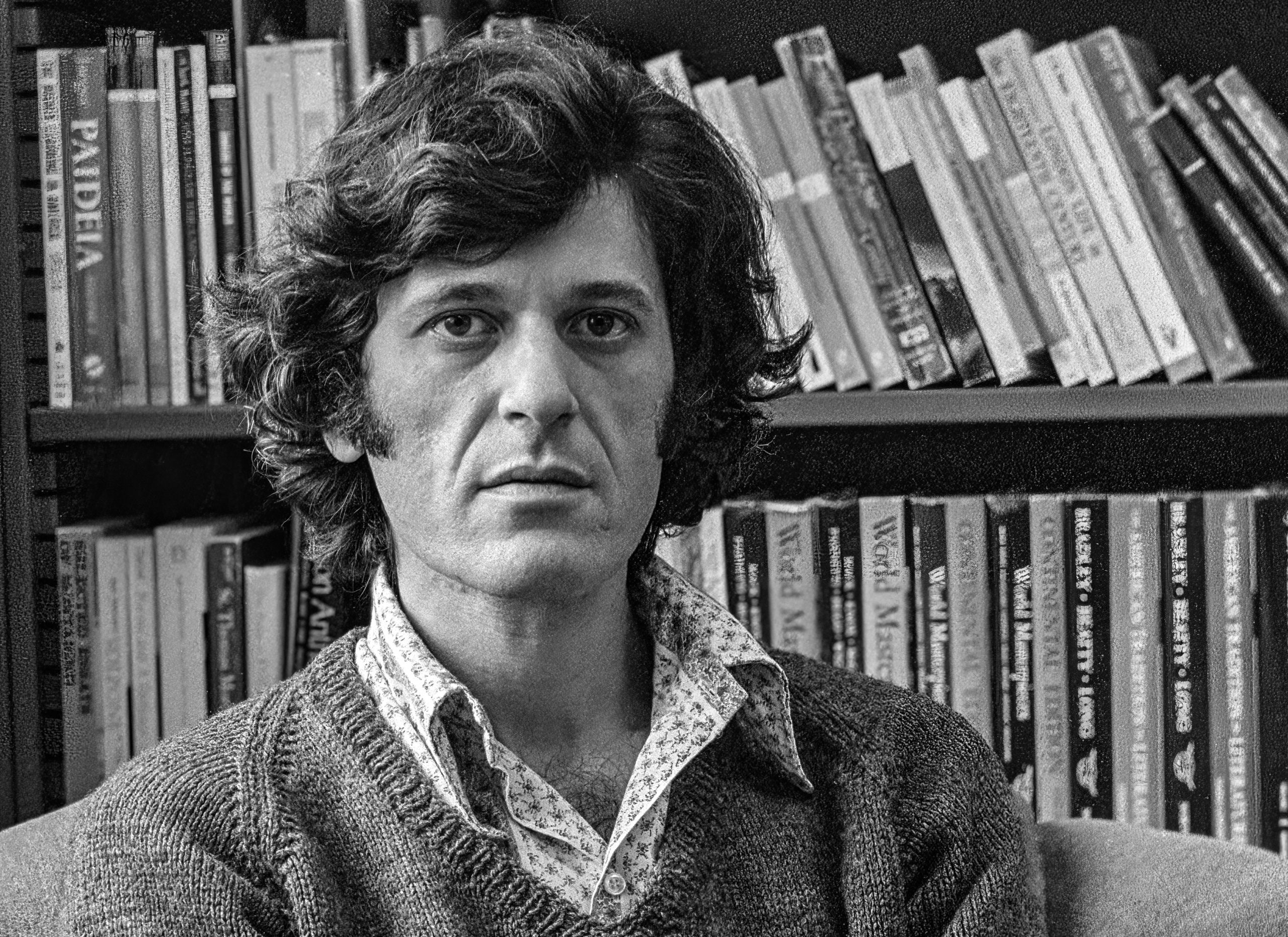

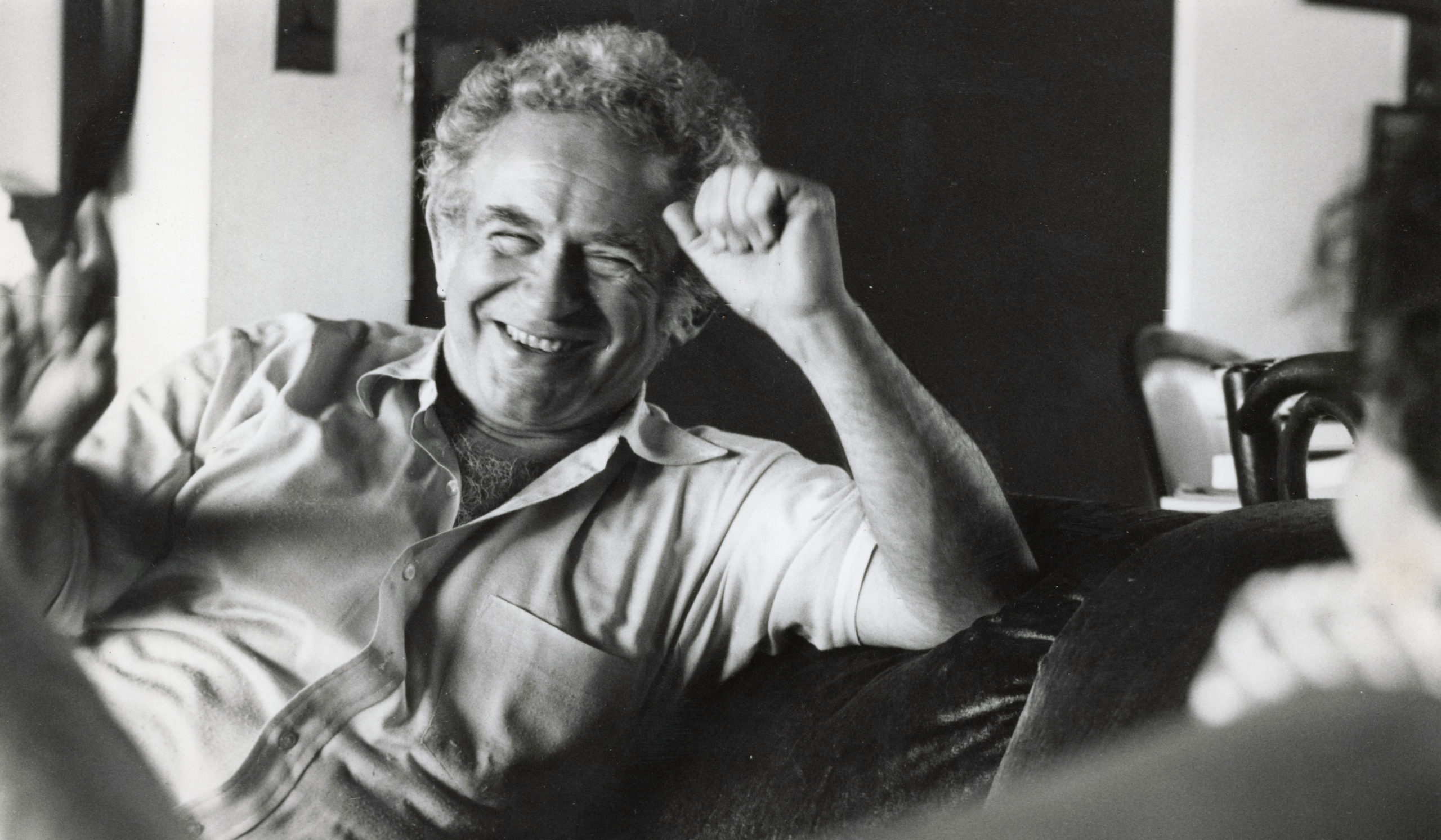

Around the turn of the last century, before the advent of emotional support avatars, Norman Mailer warned: “There is a certain passion that’s dying in American life… People are becoming less and less interested in looking at ugly problems and debating questions that are not quickly answered.… Technology has brought us further and further away from our instincts—we’re flattening out people’s spirits, we are surrounded by faces but everyone is always incredibly alone.” Since he first said these words for his PBS American Masters episode “Mailer on Mailer,” American society has moved further and further into the technological abyss. Now, a riveting documentary brings the Brooklyn literary brawler’s six-decade career as prophetic outlaw intellectual to the big screen.

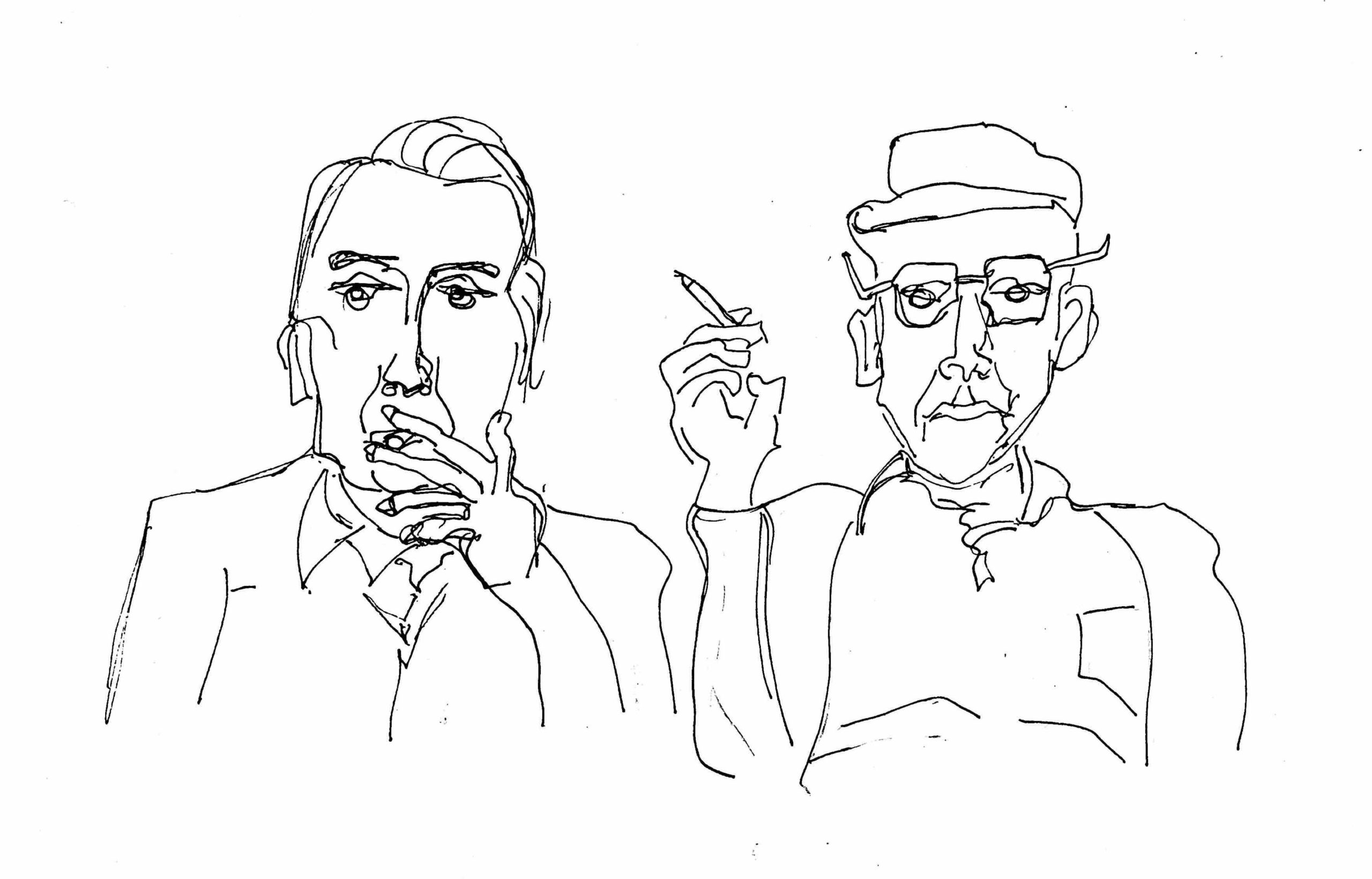

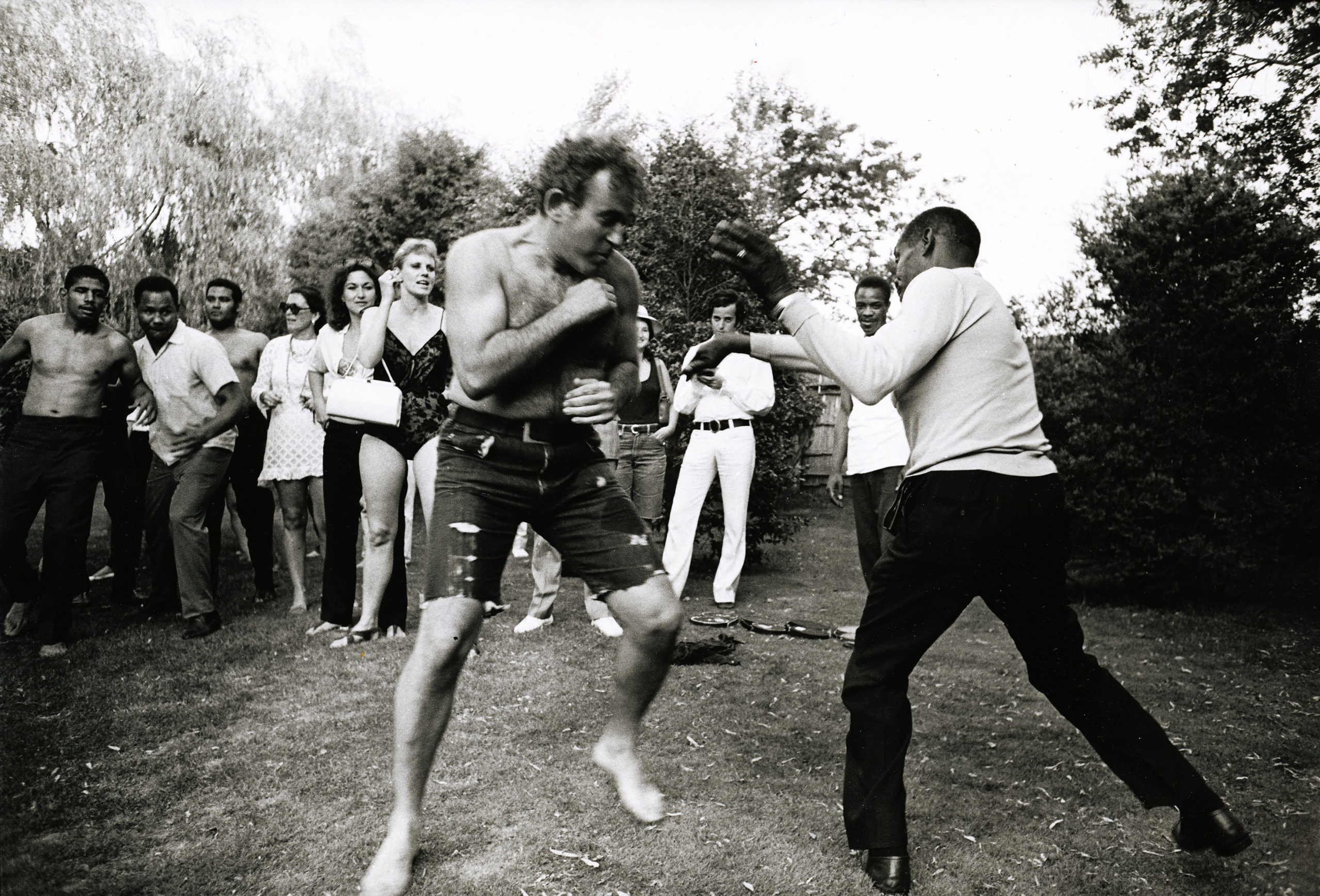

How to Come Alive With Norman Mailer (limited theatrical release July 12th, 2024), directed by Jeff Zimbalist (Pele: Birth of a Legend, Skywalkers: A Love Story), encapsulates a good deal of Mailer’s captivating life into 100 high-energy minutes. Made with the full cooperation of the Mailer family (normally the “kiss of death” for projects like these), Zimbalist and co.’s picture manages to include many of the author’s numerous messy moments—starting with the 1961 stabbing of his second wife Adele Morales, eventually detailing his maelstrom of a cinema-verité film, 1970’s Maidstone, his tête-à-tête with the Feminist movement, 1971’s Town Bloody Hall, the 1981 murder scandal involving ex-convict Jack Henry Abbott, and many, many controversies before and after. Mailer was, for good and ill, an electrifying individual and How to Come Alive offsets the static conventionality of the cradle-to-grave narrative by arranging itself around his seven guiding “rules” or principles for “coming alive”—e.g., “Don’t Be a Nice Jewish Boy from Brooklyn,” “Be Wrong More Often than You’re Right,” “Be Willing to Die for an Idea.”

“My feeling is nobody said writers had to be nice,” Mailer says in voice-over. “I’m not interested in having people think the way I think but that they get better in the way they think… We’re learning to have a false sense of what we know because of how easily the information comes.” Ever piqued and guided by Mailer’s words, what emerges is a complex portrait of a man in perpetual rebellion, battling the often violent contradictory forces in himself and the stultifying tendencies of American consumerism and recurrent moral panic. After the stunning success of The Naked and the Dead, which made him a bestseller at the age of twenty-five, he proceeded to feint left whenever he was expected to go right—like the boxers he so revered—upsetting the literary status quo with his commitment to visceral depictions of American hypocrisy, the primacy of sex and violence, and a narrative self-obsession that would eventually reinvigorate the complacency of mid-century American literature with 1968’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Armies of the Night, the apotheosis of the burgeoning New Journalism. Featured throughout How to Come Alive is cogent commentary by all of Mailer’s children, his surviving sister, his surviving ex-wives, and his many friends, fellow writers, critics, and filmmakers, including James Wolcott, Oliver Stone, Jonathan Lethem, and Germaine Greer. “Romantically reckless,” offers Gay Talese, “that was Norman.”

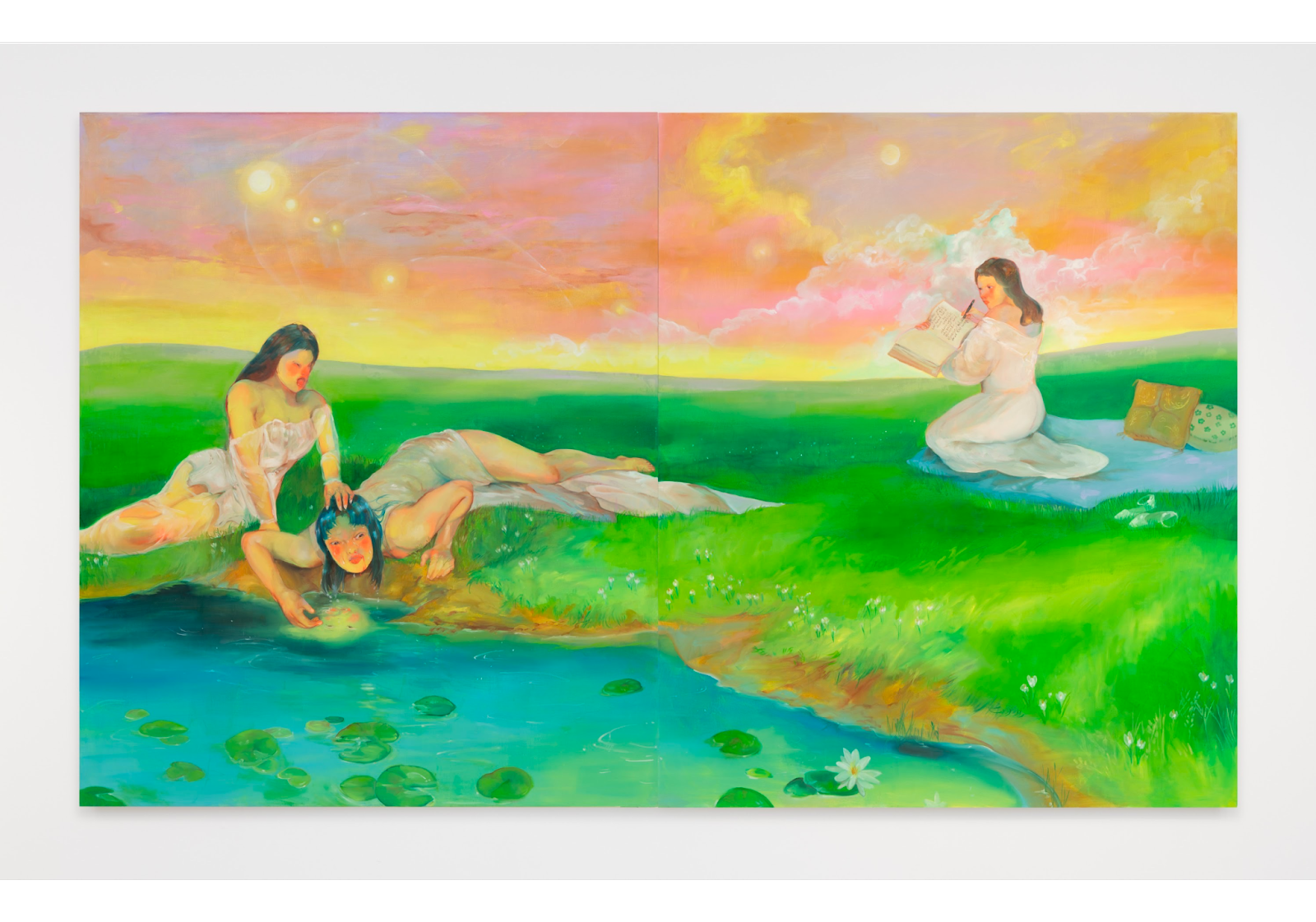

Like his writing, Mailer demands absolute engagement, and the cinema is the only place to immerse yourself to the proper degree. His thorny, often paradoxical lines of thinking simply cannot be reckoned with when one eye is on the screen and the other is on your phone while you’re spraddled on your bog of a couch. Zimbalist’s bold visual juxtapositions work very much in the Mailer vein, like when the passage of Rojack murdering his wife from 1965’s An American Dream is complemented by fireworks bursting in the night sky; while all throughout clips and stills after clips and stills (perhaps no writer in history was so exhaustingly captured on film) are deftly edited so that the twentieth century is raised to Mailer’s voltage.

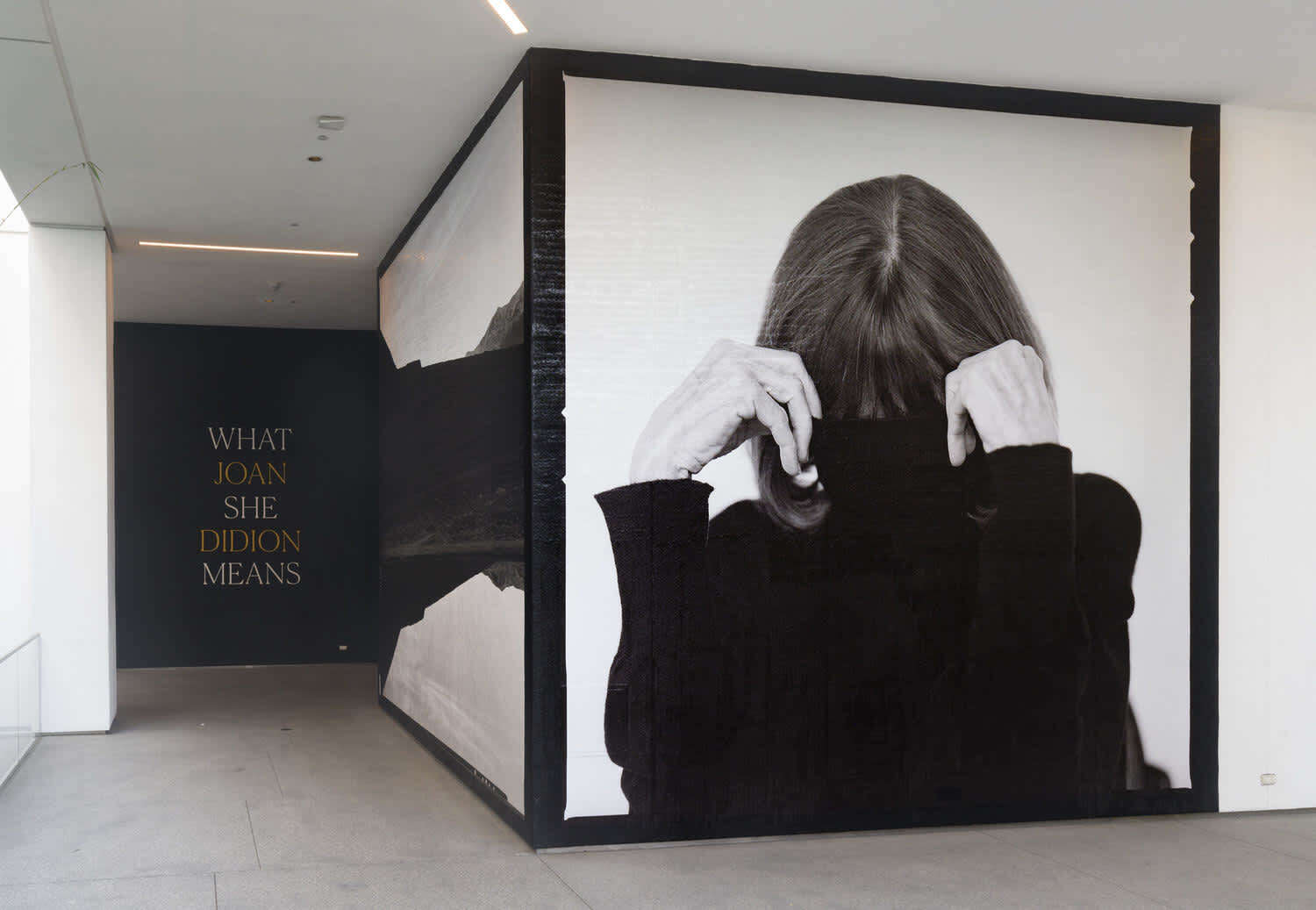

The documentary is weakest, however, as it draws to a close, when it tries to wrap its many parts into a convenient summary for our day. First, it lingers while rhapsodizing the reformed old lion, the “elder statesman of letters” who’d mellowed with age and made peace with his many sins, the darling of his massive brood. We are assured that he never forgave himself for stabbing his wife, although as an artist he had no choice but to double down (as he did with An American Dream, which he began to write less than three years later). There is little assessment of the final novels—sometimes downright shoddy, and whose compensating merits remain debatable—simply casting them as evidence of his everlasting engagement with “titanic” subjects like Ancient Egypt, Jesus, and Hitler. Curiously, there’s no mention of “The White Negro,” his highly controversial essay on the violent hipster type (which sparked a whole new uproar last year around a scheduled collection of his essays intended to commemorate his centennial; the collection was shelved). And where are the barbs from anyone even tangentially related to any of the many people he feuded with—a brand of trial by fire he practically basked in?

But as the kids gather around his deathbed and old, mute Mailer’s eyes are described as lighting up with a twinkle when he takes one last sip of rum and orange juice, you can’t help but feel moisture welling up at the lower punctums. Then comes the predictably sententious rallying cry against “cancel culture,” which, while a genuine annoyance, is an essentially lazy term at this point, and one that lends itself too easily as a sort of Frankenstein creature for the Right to animate with a farrago of the Left’s fixations and preoccupations. It’s a squandered opportunity to use the subject to make Mailer new, to wake us up with another Maileresque one-two-three punch combo. Neither Mailer—nor Orwell for that matter—would recycle a phrase as hackneyed as “cancel culture” to decry one of the many ticks clinging to the buttocks of public discourse.

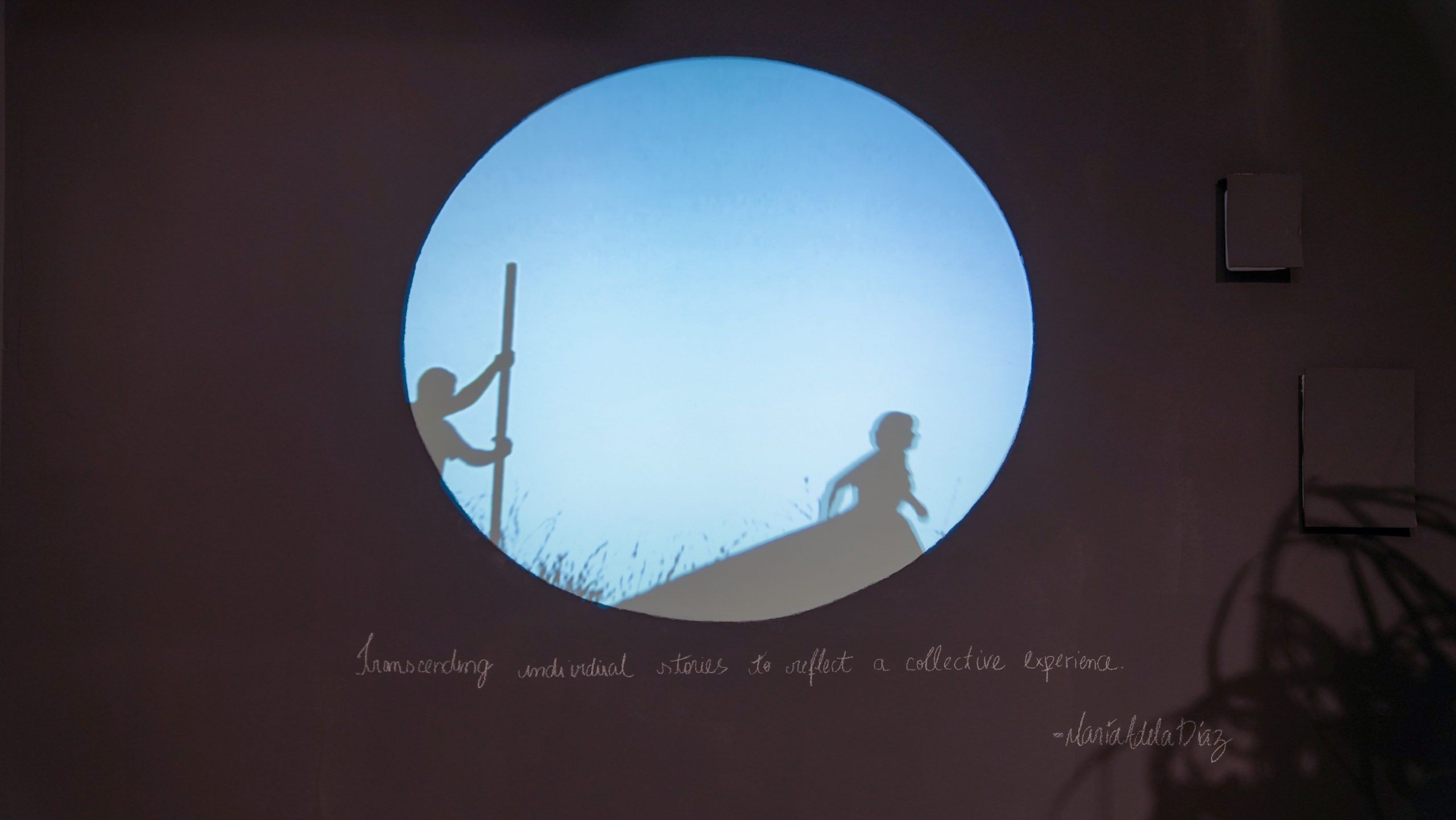

So why Norman? Zimbalist credits Mailer’s prescience of the pitfalls of modern civilization, along with his singular, unabashed courage to offer creative—if extravagant—solutions as being of singular usefulness today. Mailer repelled reductive, singular definitions and it’s his extravagance of spirit that is clearly the film’s guiding light. “I hope,” Zimbalist revealed after the screening, “it can serve as a sort of litmus test for finding the limits you’re comfortable with.” “A cautionary tale,” the subtitle reads.

In many ways, watching a film where Mailer rationalizes his thoughts and behaviors in the face of contemporary America’s onslaught of cheapness, its obsession with an almost lobotomized pragmatism that itself is a mechanical oppression, reminded me why it’s perhaps useful I have yet to “outgrow” my own anger, my unwillingness to excuse America’s inability to live up to the lofty ideals it set for itself. If you believe in them, you expect accountability. “I’ve lost respect for it,” Mailer said in a 1999 BBC documentary, “I sit there in a certain unhappiness with respect to my country. It has not become as great and as noble as I’ve wanted it to become.” And so we cannot accept indefinitely the placebo of “consumer choice” in exchange for this constant traducing, sullying, exploiting, and downgrading of democracy.

“When we just feel a dull depression, it’s very hard to love. It’s that nice mixture of love and anger that we need to come alive,” Mailer advises. And coming alive, as the film suggests, is to be instinctively aware that the business of life is not in the act of being, but in the persistent friction of becoming.

How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer

Jeff Zimbalist

102’, 2023, USA

(limited theatrical run from July 12th)