[drop-cap]

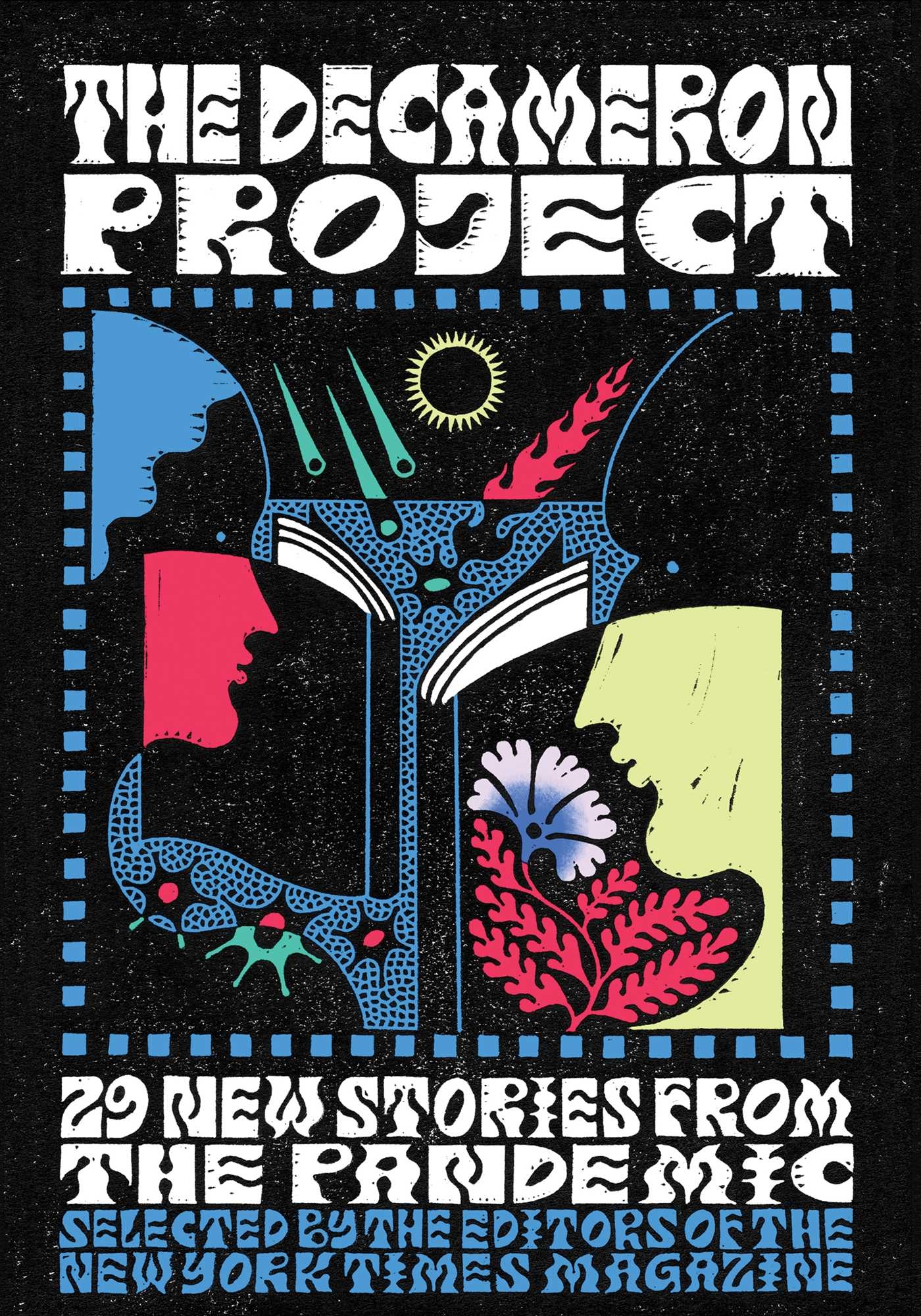

In the year 2020 millions of people got sick, went mad, and hated one another like never before. Foreseeing, or perhaps intuiting how the pandemic would unfix normalized and imperfect ways of living worldwide, the editors at the New York Times Magazine commissioned a group of fiction writers to channel Boccaccio and build stories of solace for the belabored mind. The result is The Decameron Project, a collection of 29 stories first published in the Magazine in July that remember, lament, and escape a strange and deadly contemporary moment.

The most memorable stories in this collection, the ones that mold life, not death masks out of the past year, are the strangest. At the front of the line is Téa Obreht’s “The Morningside.” Written in the folklore style of her novel The Tiger’s Wife, it begins in a distant past, “Long ago, back when everyone had gone”—where and why everyone had gone is never revealed—and tells of a mysterious woman and her dogs who live on the 14th floor of a tower. Quiet surprises—an exchange between the dogs and a macaw, the mystical ontology of the woman’s painting—move the story along to where it sighs in a somber present neither like, nor unlike, 2020. This is, after all, a tale.

While other writers in the Project render in explicit detail the precise moment in which they were commissioned by the Times (Liz Moore’s “Clinical Notes” begins with the heading “March 12, 2020”), it’s Obreht’s refusal to situate her story in or around the coronavirus pandemic, hinting only sparingly at why people are “gone” that, perhaps paradoxically, lets one see anew and from afar all that we have lost. This illusion of a break in time-space affords rest, what Kurt Vonnegut might have called a Buddhist catnap, from a tangled present we have barely outrun.

Charles Yu also avoids the scar of a specific, instantly dated time in March in “Systems,” an innovative sketch of life in lockdown from the perspective of an internet search engine. His protagonist is a collective, neurotic, afflicted “They,” (hint: all of us), who searches nonstop for people, answers, and remedies with the obsessive compulsiveness of the most ardent cyborg:

They search for things: First date ideas. Tapas bars. Tapas downtown. Wuhan. Wuhan where. Sushi near me. How to tell if he’s interested. How to tell if she’s interested. Good first date how to tell. Second date ideas. Italy. Lombardy Italy. Chinese virus. Trump Chinese virus. Coronavirus versus flu. Covid not that bad.

The humor here, like in Wu’s Interior Chinatown, is crushing, but, as the writer Rebecca Brown likes to say, “Humor orbits a dark sun,” and Wu ends up placing a mirror in front of the ways we search online and leapfrog wildly from question to question: “Why do some people say coronavirus not that bad. News sources trustworthy. Fauci. Fauci credentials. Fauci facepalm gif.” In these fast-paced vignettes question marks vanish like religions, replaced with the deadpan period of “They’s” digital syntax, a syntax of searching which the pandemic has shape-shifted into suffering.

Boccaccio most likely began writing the Decameron in 1348, not long after the onset of the Black Plague, and finished in 1352. With a handful of editors and just shy of thirty writers, the NYT Magazine made shorter work of the coronavirus pandemic, taking just four months to bring their project from pitch (March) to publication (July). Somehow they did this with enough writers from diverse backgrounds to keep BuzzFeed at bay (the collection features writers from China to Chile). But whether or not all of the writers do, as the editors say, “help readers understand the present moment” and “provide delight and consolation during a dark and unsteady time,” is uncertain. Some of the stories soar in and out of the pandemic. Some were written too fast.

And this “unsteady time” is, notably, only the early days of the pandemic. Had the Project longer to gestate through a year uncut not just with a deadly virus but also intense race consciousness and an enervating presidential election, it’s possible that a few ACABs might have sprouted in the stories, or maybe a gunslinging Proud Boy, or the never-ending knitting needles of nasal swabs. Maybe the absence of these and other “characters” is passable, even unremarkable. No text can say everything about a moment, and what the Project misses of 2020 it fills with stories that swelter in some of the enduring cultural heat waves of the past five years.

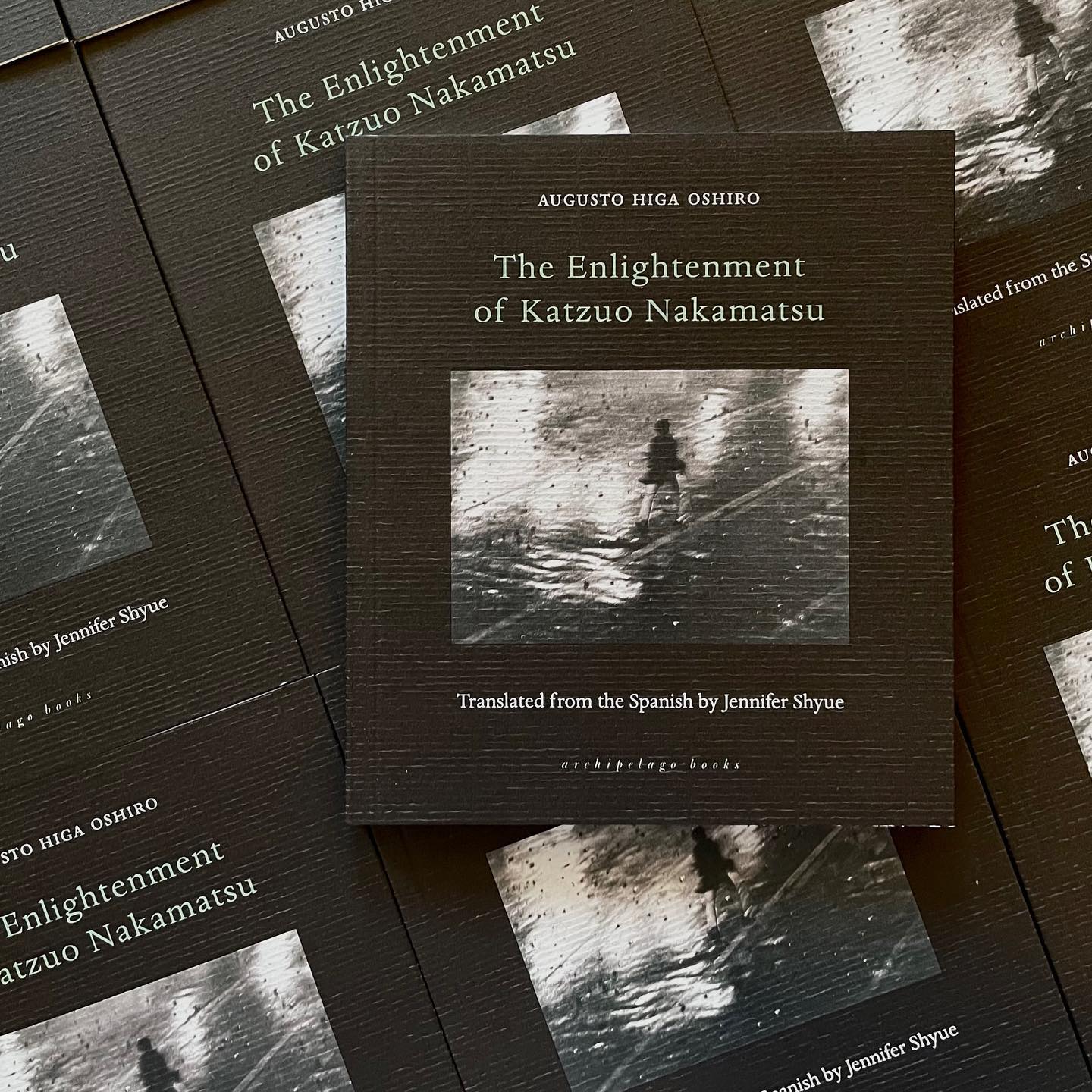

The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic

edited by The New York Times Magazine

Scribner, $25.00