[drop-cap]

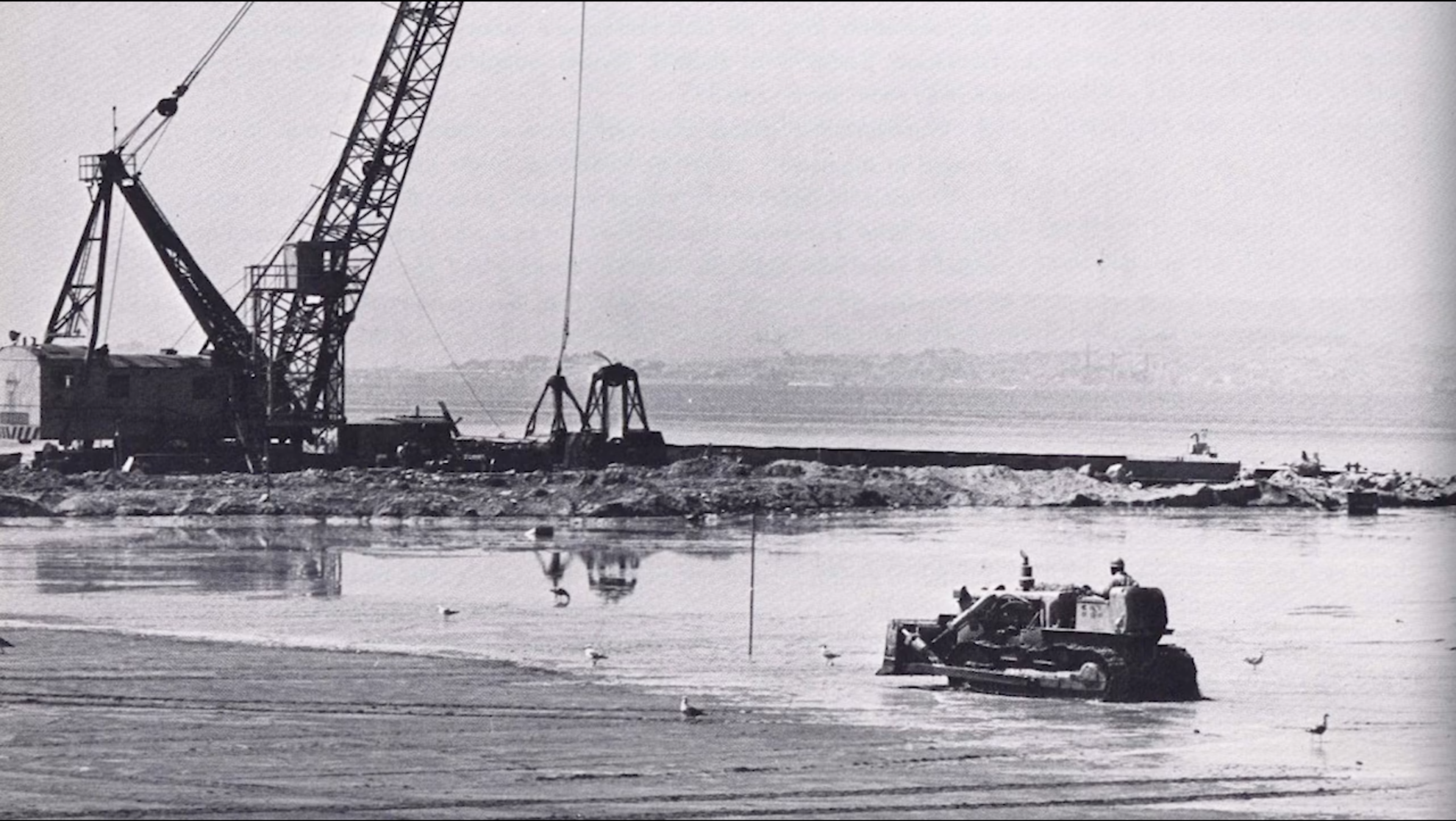

In 1961, the shores of San Francisco bay were an industrial playground of debris and dereliction. Ninety percent of its original wetlands had been destroyed, and what remained was either inaccessible or ripe with sewage. But as the population in each of the Bay Area’s coastal cities continued to grow, so too did their demand for land. Berkeley, for example, drew up a plan to submerge a further 2,000 acres, extending itself a mile into the water. At this rate of drainage, the Army Corps of Engineers complacently projected that the Bay would be no bigger than a narrow shipping channel by 2020. Everyone, it seemed, felt that the water was beyond saving. Everyone, that is, but Kay Kerr, Sylvia McLaughlin, and Ester Gulick, who, with the help of their well-connected spouses (Kerr’s husband, Clark Kerr, was the president of the University of California), friends in high places, and constituents, launched the “Save the Bay” campaign that would preserve the Bay from development.

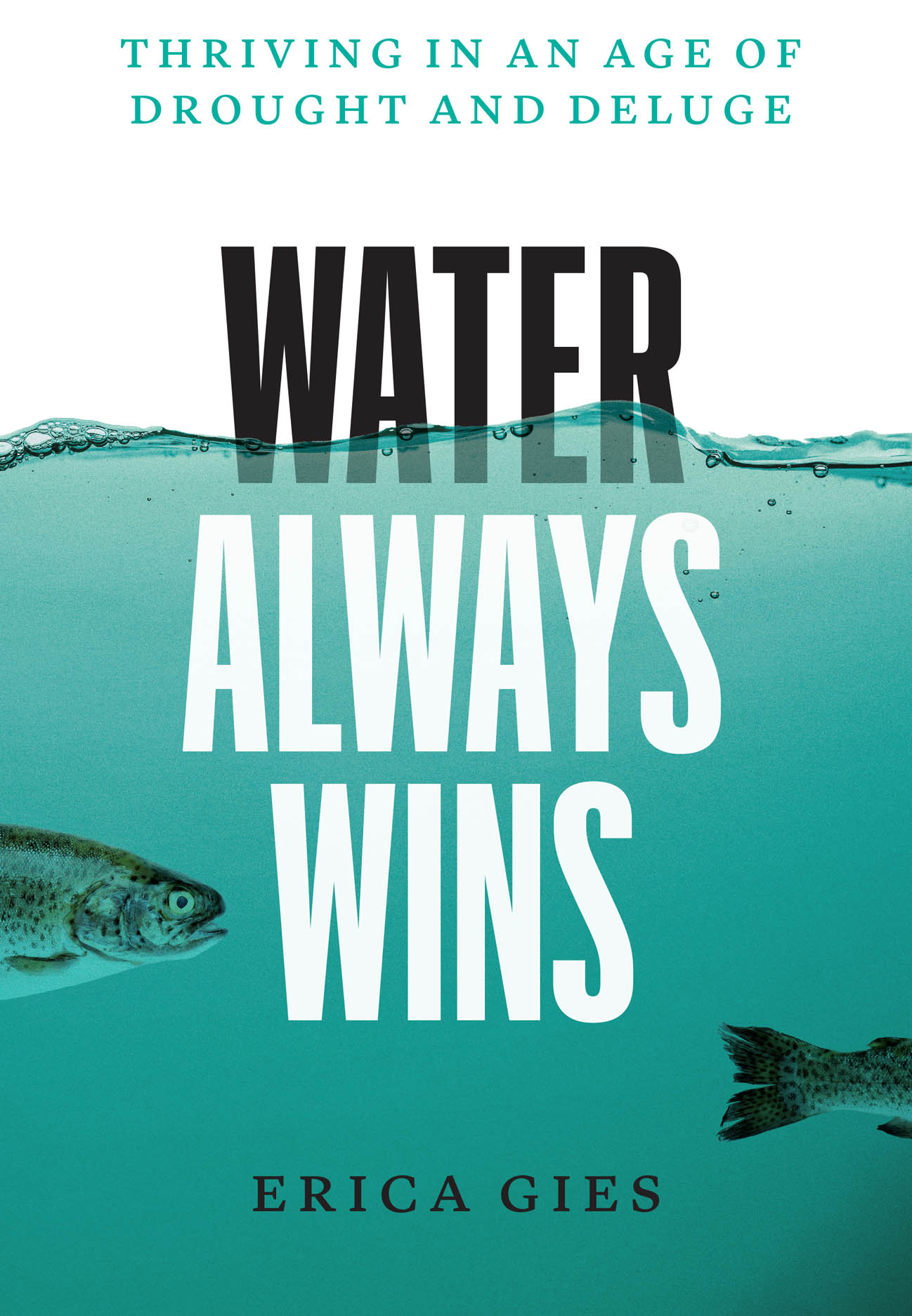

The San Francisco Bay is just one of many aqueous battlegrounds that Erica Gies, a west coast environmental journalist, visits in her new book, Water Always Wins: Thriving in an Age of Drought and Deluge. From cities to microbes, Gies guides us through the various ways that the forces of human development contest—or coexist—with forces of nature. Her book is a sort of water map that details various locations both above and below the surface where geopolitical conflict, misguided natural resource management, and poor urban planning, among myriad other human shortcomings, have led to droughts, deluge, and other calamities.

One of the waypoints on Gies’s map is Chennai, India, a coastal city that ran out of drinking water in 2019—a strange event for a city built on top of the Pallikaranai Marsh. The headlines shocked the world. But, as Gies notes, residents of Chennai were already primed to the frightening effects of water scarcity, having learned to plan their day around the few morning hours when potable tap water is accessible. Once connected to rivers, backwaters, coastal estuaries, and mangrove forests, Chennai’s years of industrial development—including impervious cement and water drainage canals to divert storm water—prevented annual monsoons from replenishing the groundwater while increasing the city’s susceptibility to destructive flooding.

Meanwhile, in the Mesopotamian marshes of Iraq (also known by biblical scholars as Eden) the Ma’dan have been struggling to maintain their traditional livelihoods amid political and developmental threats that have turned the area into a parched landscape. By building just about everything from native grasses, residents of the Al-Hammar Marsh employ a style of “amphibious housing” in accordance with the natural ecosystem. But their way of life was threatened with extinction in the 1990s when Saddam Hussein ordered the marshes to be drained, burned, and poisoned to prevent Shiite rebels from hiding there. Although the marshes have recovered to some extent, their health continues to be compromised by climate change, water diversions, and upstream dams. The viability of traditional ways of marsh-dwelling life remains in question.

Beneath these historical flashpoints, Gies digs into the science. From the microbial matter of substrate that nourishes stream ecosystems to the interconnected networks of water-retaining wetlands, she weaves us through the complexities of hydrology and the nuanced magic that happens below earth’s surface. Much of her research reveals what we cannot see—like ancient paleo valleys that help mitigate flooding, macroinvertebrates whose tunnels improve soil aeration and water flow, and microbes who create food for other lifeforms, transfer organic matter between the soil, and even aid in filtering petroleum leaks. The subtlety of these processes is perhaps the primary reason humans have found it so difficult to surrender to water—and so blindsided when water finally decides to fight back.

Gies’s solution is to develop a more harmonious relationship with water and begin seeing this powerful force as a friend instead of foe. Informed by the research of various “water detectives” (like Yu Kongjian studying “sponge cities” in China, Graham Fogg researching groundwater hydrology in the Central Valley, or Boris Ochoa-Tocachi consulting Peruvians on how to integrate indigenous traditions into modern water management) and the behavioral patterns of mother nature herself, Gies encourages us to turn away from our propensity for speed and instead embrace “slow water,” the type that sits and settles, especially in places we are quick to drain and develop.

Some areas of slow water are more aesthetically pleasing, like the lakes, ponds, and dams glossing neighborhood fliers and travel brochures. Others require a little more warming up to, like the handiwork of a beaver, whose water-filtering and habitat-providing dams usually involve an unaesthetic disarray of twigs and chewed logs. Or the floodplains, marshes, and wetlands that grant sustenance to birds and insects, spaces for interacting waterways to exchange nutrients and filter water, and time for water to trickle into the subsurface. Slow water can even exist miles below the surface in the hyporheic zone, also known as the “liver of the river,” responsible for modulating surface-level water temperature, oxygenating water, and filtering and decomposing waste. Gies is quick to qualify that slow water isn’t always pretty, but maintaining its health is essential if we want to keep things from getting ugly.

The consequences of draining and developing land prone to “slow water” hit especially close to home. California is still recovering from a recent spate of atmospheric rivers that uprooted venerable trees, overwhelmed infrastructure, and devastated communities. Overdeveloping the California coast brings its consequences too. Gies warns that by 2100 rising sea levels will displace between 190 and 630 million globally. Ironically, the destroyed marshes the Bay Area rests upon would have been prime candidates for keeping up with sea level rise. Restoration projects are underway, but the marsh needs room to grow, and the space it wants is occupied by urban infrastructure, such as the Google and Facebook campuses.

Restoring our relationship with water also means acquiescing to water’s memory, which is far more reliable than our own. It’s easy to forget, Gies tells us, that iconic landscapes like the oak woodlands of California’s Central Valley used to be wetlands, drained and diked to provide water for the state’s agricultural production, or that what is known today as the Corn Belt used to be a swamp. In the Midwest, generations of drainage have ingrained such a commitment to modern methods that when the Army Corps of Engineers tried to restore habitat through levee removal, they were sued by local residents for attempting “military hydrological complex projects.”

As with any battle, finding a more mutually beneficial solution to our water woes won’t be easy. But, as Gies and her counterparts stress, the best way to live with water is not to fight it. Whether we acknowledge it or not, “water still wants to flow its innate path,” and it’s up to us to decide if we want to continue getting in its way.

Water Always Wins: Thriving in an Age of Drought and Deluge

by Erica Gies

University of Chicago Press, 2022

$26.00