“There is more than one kind of freedom. Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don't underrate it.”

-Aunt Lydia, The Handmaid's Tale

[drop-cap]

In the future, everyone will be politically correct, climate-conscious vegans. And everyone will like it.

No one will have a choice.

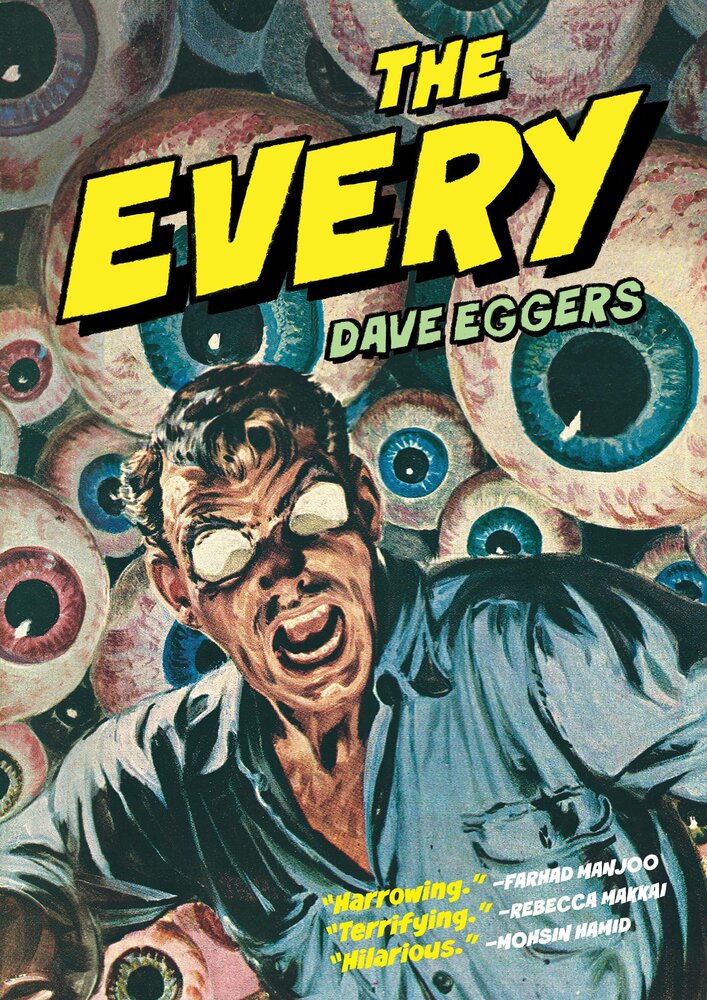

This is the promise of the Every, the eponymous corporation at the center of Dave Eggers’ new novel. A sequel to The Circle (2013), The Every picks up five years after the tech giant of the first book acquires an e-commerce juggernaut known only as “the jungle.” Combining the businesses of Google, Apple, Twitter, Facebook, and, yes, Amazon, Eggers frames the Every as Frankenstein’s tech monopoly, lumbering into the future as the literary townspeople watch in horror.

We follow Idaho-born Delaney Wells, one-time forest ranger and daughter of local grocers. Her Sisyphean goal: taking down the Every from the inside. With help from her friend Wes, a programmer, Delaney embarks on a mission to seed the company with ideas so ludicrous, so outrageous, that the general public will be forced to collectively cancel their one-stop-shop for everything online. Mae Holland, the impossibly naïve, Kool-Aid-drinking protagonist of The Circle, returns as CEO.

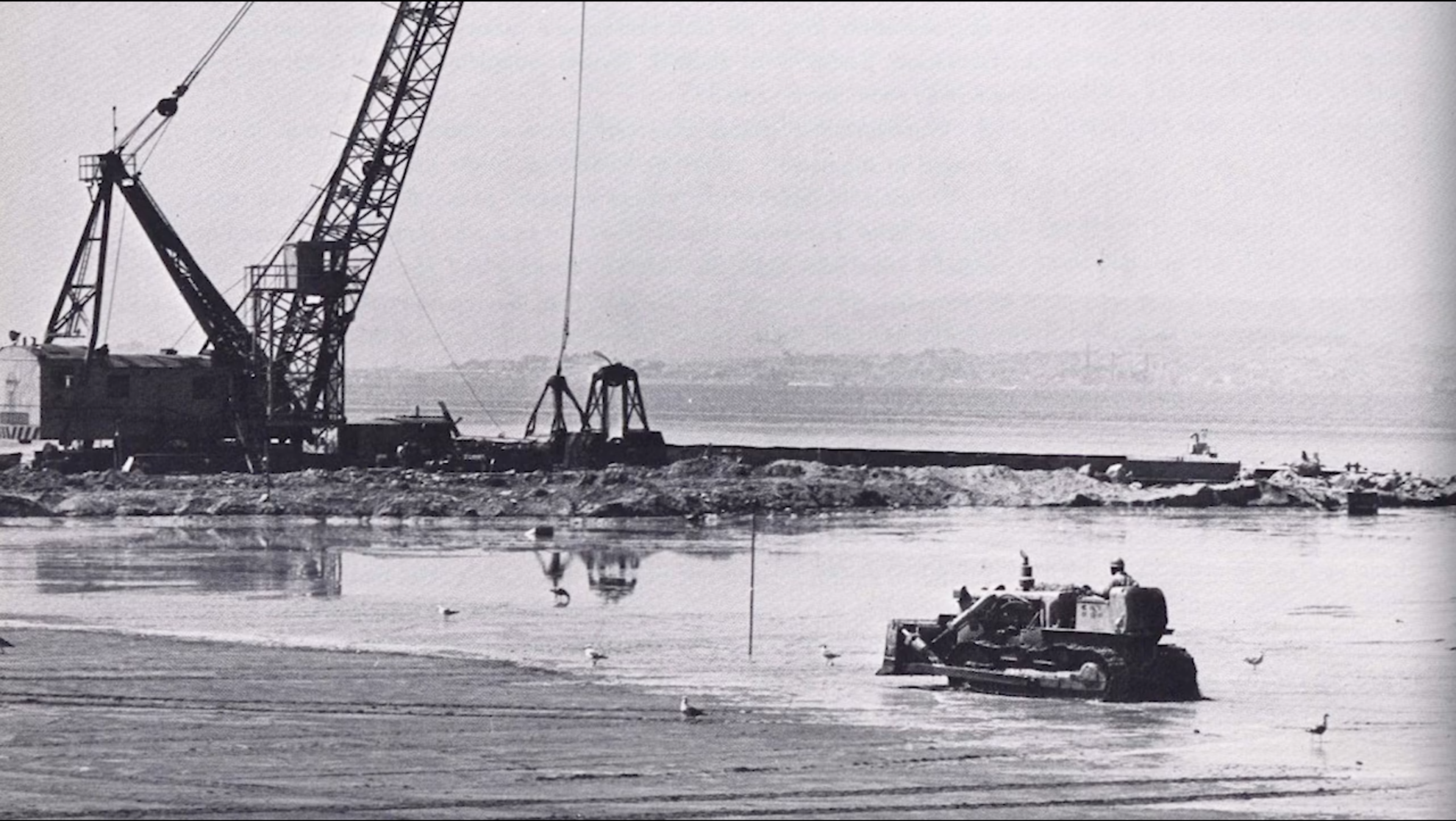

Safely isolated from the rest of the Bay Area on Treasure Island, the Every campus comes off like a deranged, corporate-sponsored B.F. Skinner experiment. Twitchy employees rely on notifications to guide their thoughts. Lucite podiums dot TED-talk-friendly auditoriums. Security stops all single-use packaging at the door. Lycra, for some reason, hugs every crotch.

Lacking a coherent plan, Delaney’s efforts as wannabe agent provocateur mimic the meandering plot. She and Wes nudge on the info-apocalypse one laughably toxic idea at a time, without really changing anything.

But the novel shines in its doublespeak-laden descriptions of Every services, aided by the author’s command of California English and his scorching contempt for the tech world. Although the dialogue-heavy demonstrations occasionally slump into familiar op-ed musings, the sheer scope of app-derived unhappiness elicits morbid fascination, much like the viral videos of police brutality the Every servers host.

In The Every’s Foucauldian nightmare world, every purchase, every song, every dietary choice, is burdened by the judgmental gaze of millions. It’s a culture where individuals linger on every word, assessing whether it might cause offense to someone, somewhere. Where the most innocuous actions become unabsolvable hate crimes. Where trackers enforce “eyeshame” on errant glances.

An encyclopedia of all-too-believable industry euphemisms dot the book. Employees aren’t fired; they’re deëmployed. Consumers aren’t spied upon; they’re de-anonymized. Ideas aren’t suppressed; they’re de-elevated. Breathless lists of absurd products highlight the author’s themes:

There’s FaceIt, an algorithmic ranking of a person’s attractiveness. TruVoice, a text and speech filter that eliminates offensive language. Friendy, a tool that rates your friendships. And Concensus, an app that puts everyday choices to a vote. Perhaps most disturbingly lifelike is Samaritan, a network for reporting objectionable behavior, resulting in an overall “Shame Aggregate.”

Delaney eventually realizes the truth: nothing goes too far. There are no limits to the public appetite for surveillance. No bounds to the desire for behavioral regulations.

In The Every’s Foucauldian nightmare world, every purchase, every song, every dietary choice, is burdened by the judgmental gaze of millions. It’s a culture where individuals linger on every word, assessing whether it might cause offense to someone, somewhere. Where the most innocuous actions become unabsolvable hate crimes. Where trackers enforce “eyeshame” on errant glances.

Following a disastrous off-campus trip to see elephant seals mate, an employee coins the term “Impact Anxiety,” attempting to describe his fear of the “impossible to justify” consequences of practically any real-world encounter—on both the environment and his own delicate psyche. Delivered in a baby-blue kilt over a bodysuit, his presentation plays to comedic effect. But Impact Anxiety reflects a pernicious form of self-subjugation. And the actual services satirized by The Every promote it.

When Mark Zuckerberg implies that sharing is the only way to make the world a virtuous whole, the language he uses turns that performative submission into empowerment. But unlimited sharing also invites endless comparison. Endless comparison builds limitless opportunity costs into every choice, turning previously sheltered decisions into sources of potentially infinite regret.

Those who’ve come of age under Zuckerberg’s dominion understand this well. Simply living becomes a performance to an unseen audience. Incessant, crowdsourced moderation becomes self-censorship becomes empowerment, understood here as liberation from “bad” behavior.

In The Circle, Mae blithely notes that, with millions watching, “you perform your best self.” The Every follows this logic to its surreal conclusion: the abolition of privacy, on moral grounds.

Although it’s cliched to compare dystopian novels to Nineteen Eighty-Four, in the case of The Every, with its ad absurdum extrapolations, the comparison is apt. Indeed, the focus on surveillance capitalism Eggers began in The Circle almost demands it, reliant as the first novel is on pithy axioms reminiscent of the Ministry of Truth. But The Every’s subtext is a more insidious one. It concerns our collective acquiescence to dogma.

In fact, The Every’s closest antecedent—more than the works of Orwell—may be The Handmaid’s Tale. Margaret Atwood’s 1985 exploration of America’s fascist shadow self addresses many of the same anxieties as The Every, but through the lens of the religious right, instead of militant vegans who find privacy tantamount to child abuse. In both, vocal, well-placed minorities impose their fanatical standards on the American public. Both emphasize the impossibility of escape when millions comply, afraid of being on the “wrong side.” And at their heart, both examine the evils inherent in moral crusades, while asking what causes—if any—are worth the trade-offs.

Ask yourself: which of our ideals supersedes the others? Life? Liberty? Safety?

Are animal products ethically indefensible?

Should stay-at-home orders be made permanent to avert climate catastrophe?

Would mandatory domestic surveillance prevent abuse?

Posturing on social media—signaling everything from identity to ideology—flourishes because participants know everyone is watching. Validation creates a feedback loop, drawing further engagement and conformist self-performance. That the same goes for schadenfreude hardly needs telling.

Eggers’ characters inevitably couch these questions within the language of human rights. And when these rights are framed as incompatible with privacy, as in the anti-abortion rhetoric that inspired Atwood, debate becomes impossible. The intrinsic virtue of “protecting” humanity precludes any genuine discussion.

The Every traces how our actions online, far from being the atomized, rational choices of economists, further the narratives of the loudest and most outraged without substantive debate. Its insights stem not from the surveillance of Big Brother, but from mob surveillance, and the orthodoxies it imposes. Posturing on social media—signaling everything from identity to ideology—flourishes because participants know everyone is watching. Validation creates a feedback loop, drawing further engagement and conformist self-performance. That the same goes for schadenfreude hardly needs telling.

Eggers tucks these vexing topics in with amusing, meta-referential asides. But the book would be funnier if it didn’t feel so real. With a few changes and another tacked-on subtitle it could be sold as non-fiction.

By the novel’s third act, the Every is well on its way to becoming the Only. The only retailer. The only news source. The only platform. Delaney pitches her endgame, conceived as the only way to save the world from itself: autocratic techno-communism, built from the e-commerce subscription model. Complete control over production and distribution, using personalized data, would assign an “all-encompassing Virtue Rating” to each consumer. Products and services would be allocated accordingly.

The use of the term “virtue,” which brings to mind the well-intentioned excesses of performative cancel culture, should not be understated. And the echoes of China’s Social Credit System are obvious. But seeing unrestrained, “consumer-centric” capitalism arrive at the same destination gives one pause.

It’s hard not to see our own complicity. How many of us would gladly see discourse fenced into tidy Overton windows, social media scrubbed clean of references to critical race theory, or problematic transphobia? We vilify others’ behaviors. Crave validation from those we’ve never met. Desperately seek lives free from all we disagree with.

A sudden shift to Mae’s perspective presages the novel’s grim conclusion. The final pages culminate in a soliloquy fit for Orwell or Atwood:

Where there had been din and disorder there would be the quiet hum of a machine that saw all, knew all, and knew best—that was committed to the perfection of people and the salvation of the planet.

That we form the gears of this machine is left unsaid.

Four out of Five Atwood’s.

The Every

by Dave Eggers

McSweeney's, $28.00