“I guess you’d say / I’m on my way / to Burma-Shave”

—Tom Waits, “Burma-Shave," 1977

[drop-cap]

“What do we care? Anywhere we choose." Those are the fated words of Frank Chambers in The Postman Always Rings Twice, James M. Cain’s 1934 novel about a drifter who turns up at a roadside diner-service station on the outskirts of Los Angeles and shacks up with the proprietor’s wife. Although Postman masqueraded as a hard-boiled tale of adultery and punishment, sultry currents of resentment, restlessness, and disastrously fulfilled wishes bubbled just underneath. A sensational bestseller, The Postman Always Rings Twice was a critical success that seemed to expose some long-suppressed primal truth about the American character.

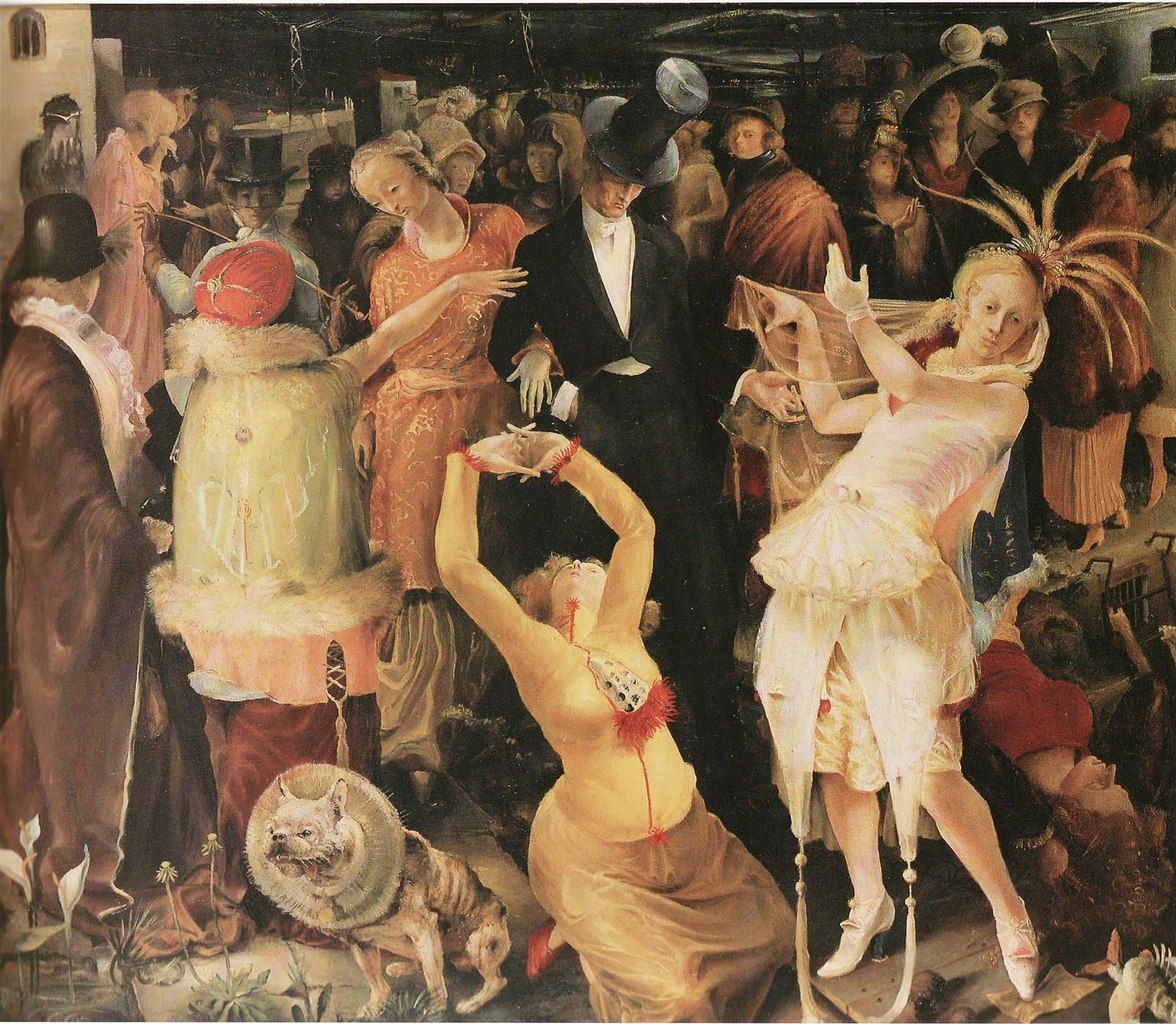

It was the midpoint of the Depression and a number of Americans, including the no-longer-young like Frank Chambers, were still feeling confined by their circumstances, despite the results of the 1932 presidential election. Many of them longed for some sort of retribution, and if they couldn’t get it—escape. And escape they got. Radio thrust the disembodied voice into homes, where words floated in air like biblical pronouncements. Comic books brought ironies to life in swatches of primary colors and exclamation points. And the newspapers, in their notionally no-nonsense style, reported on a new

type of violent criminal: the roving bank-robber. Tales of Dillinger, Bonnie & Clyde, and the FBI’s Most Wanted list foisted big personalities and small towns into public consciousness. Everyday, as it shattered another limit imposed by time and space, America grew just that little bit smaller.

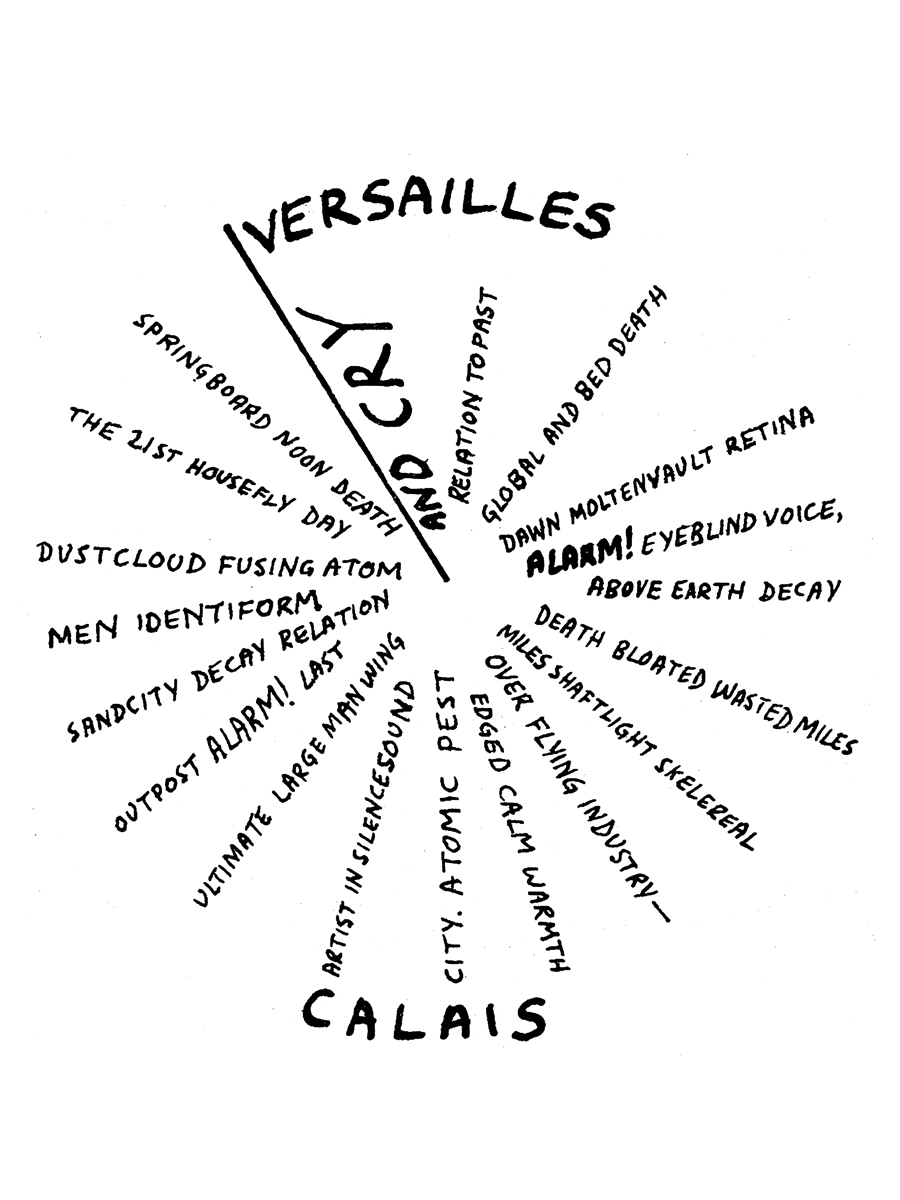

A growing array of colorful, gimmicky signage battled for everyone’s attention, hawking products and perspectives to anyone with eyes to see and ears to hear: WALK A MILE FOR A CAMEL; NEW FORD V-8; FREEDOM, OPPORTUNITY, PRIVATE ENTERPRISE, REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY—IT’S THE AMERICAN WAY! As the decade marched on, the experience intensified, forcefully mounting like a locomotive huffing and puffing to mechanical hoofbeats, hisses and whistles and static and chatter, Fireside Chats over the airwaves like Artie Shaw, Delta blues, and The Shadow; from the motormouth buzz of Howard Hawks to the syrupy fuzz of Clara Cluck, more and more a deluge of stuff, love songs and dance halls, typewriters, telegrams, and telephone calls, Argosy, Black Mask, and Popular Western, while candybars, hosiery, and aftershave-filled diesel trucks crisscrossed Works Progress Administration bridges all aboard that train of that swell of that coming American BOOM!

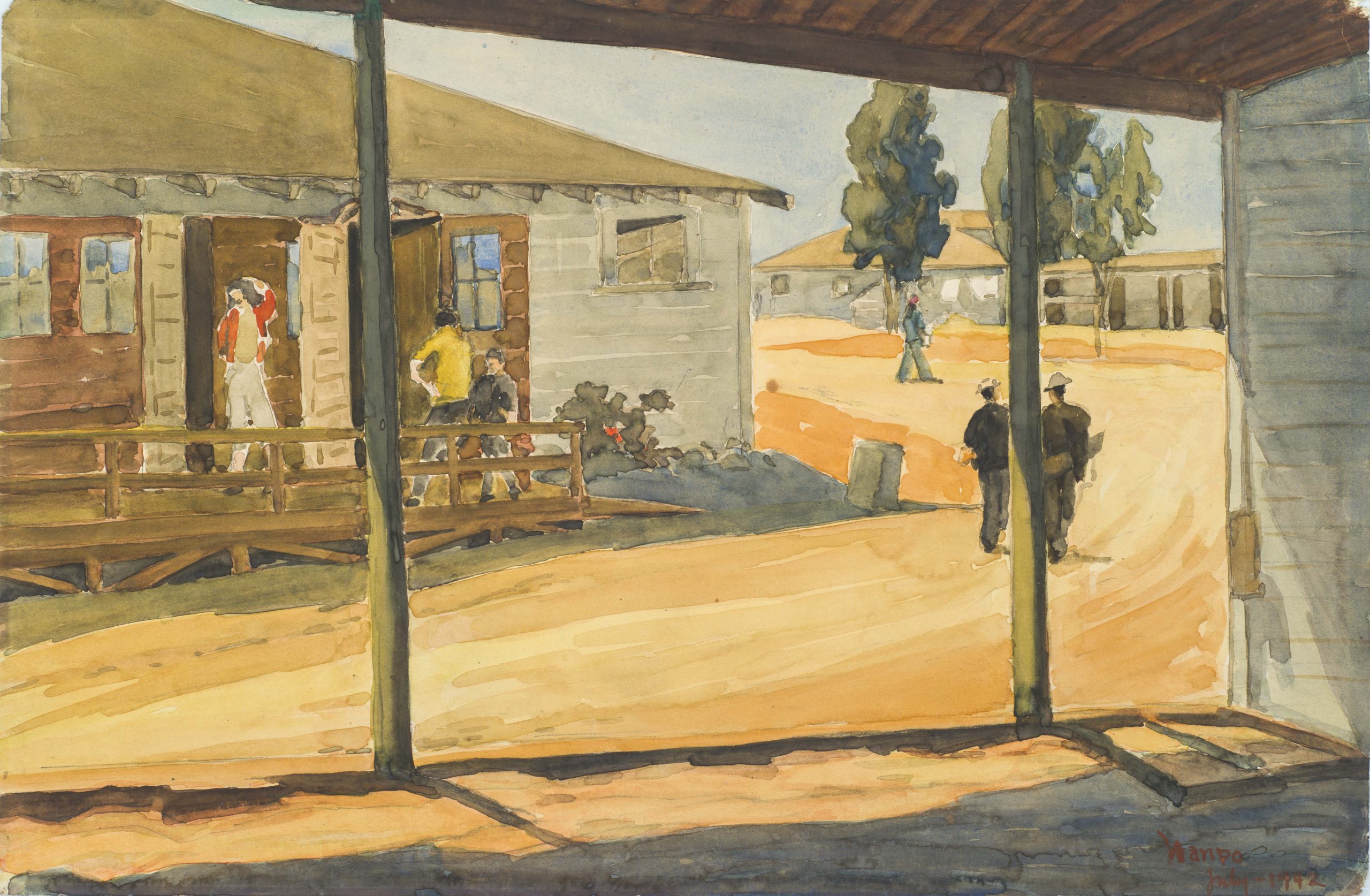

Edward Joseph Ruscha IV was born in the vast flats of Omaha, Nebraska, in 1937—the same year as Batman and Look magazine. The Ruschas moved to Oklahoma City when little Ed was four. His father, Ed Sr. (born in Missouri, whose father was born in Missouri, whose father’s father was born in Missouri), worked for the Hartford Insurance Company. In Ruscha’s words, Ed Sr. “made very little money, but he had a modest expense account and a company car,” and once a year the family would go on a road trip. Regular drives into John Ford country, Monument Valley, the Grand Canyon, cactus plants, gnarled boulders, Redwood trees, California. “We never went east.”

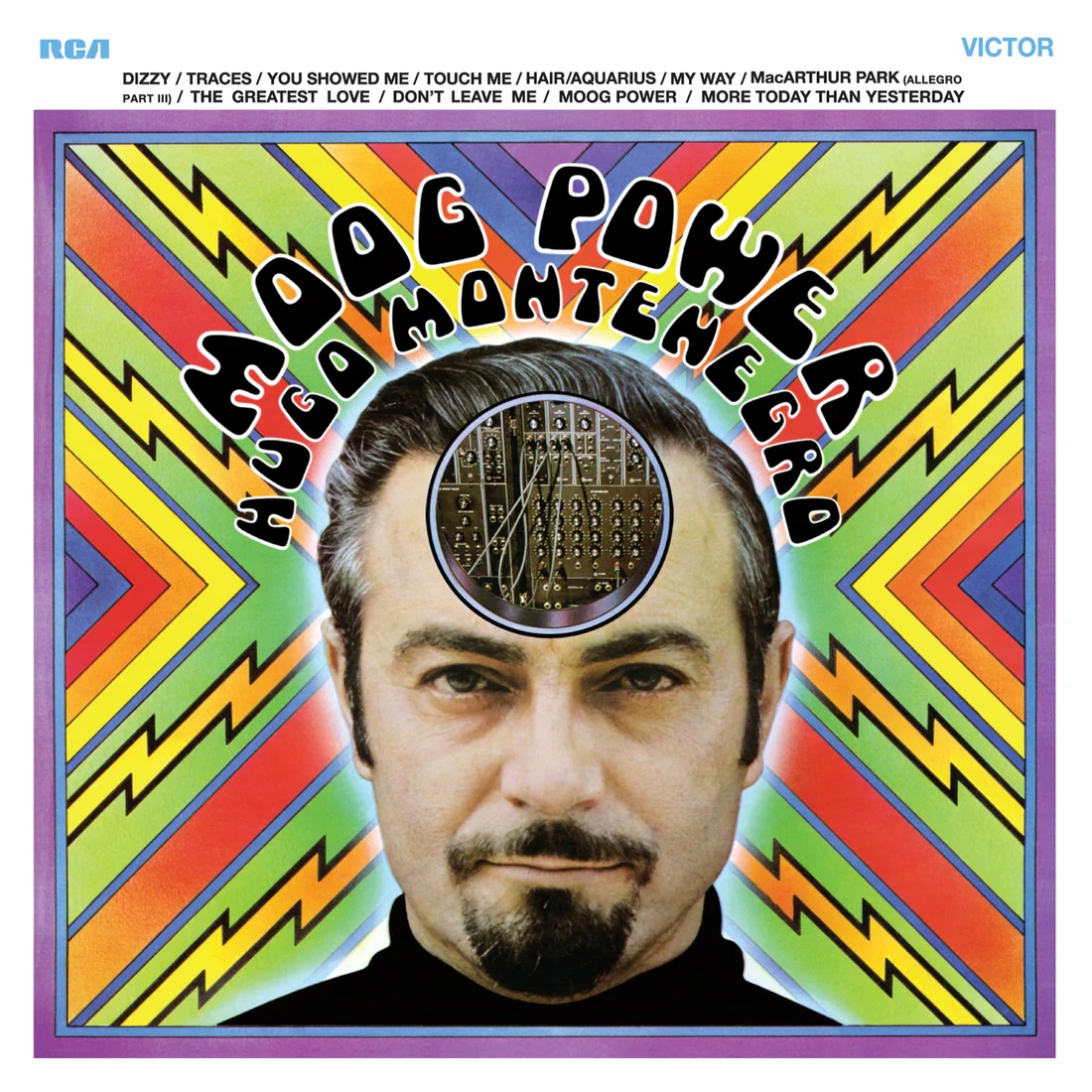

Ruscha grew up Catholic and was drawn to the aesthetics of indoctrination—the vestments, the incense, the painted stations. He also drew cartoons, inducted into the practice by a neighbor kid two doors down who kept the whole history of Dick Tracy in a tin box. In 1954, at the age of 16, Ruscha hitchhiked across the country for the first time. The Eisenhower ‘50s were an age of unchecked abundance, characterized by a swarm of prospering Americans—desperate only two decades ago—hitting the Interstate Highways for the newly-risen suburbs with a hankering for white-picket fences and Pontiac Catalinas. The clothes were better, the food more conveniently packaged, and the cars were—like Gothic cathedrals of yore—the supreme creations of the era. By 18, Ruscha was determined to become a commercial illustrator and applied to the illustrious ArtCenter College of Design in Los Angeles. Along with his close friend Mason Williams (a folk and country-singing guitar player), he packed his belongings into a 1950 Ford sedan and left Oklahoma City in 1957 along Route 66, burning quarts of oil all the way.

Ruscha was not accepted to ArtCenter. Instead, he enrolled at the Chouinard Institute (now CalArts) down the street from MacArthur Park and moved into a small apartment he shared with three other artists on Sunset Place, off Hoover. At Chouinard, Ruscha’s courses in fine art emphasized spontaneity and gesture, while his design courses fostered precision and balance. The dueling forces of art and commerce quickly ushered in potent juxtapositions of high and low in his work, and he soon developed a hyper-precise style that aligned with the blossoming lushness of pop music—everyday experiences, highly produced.

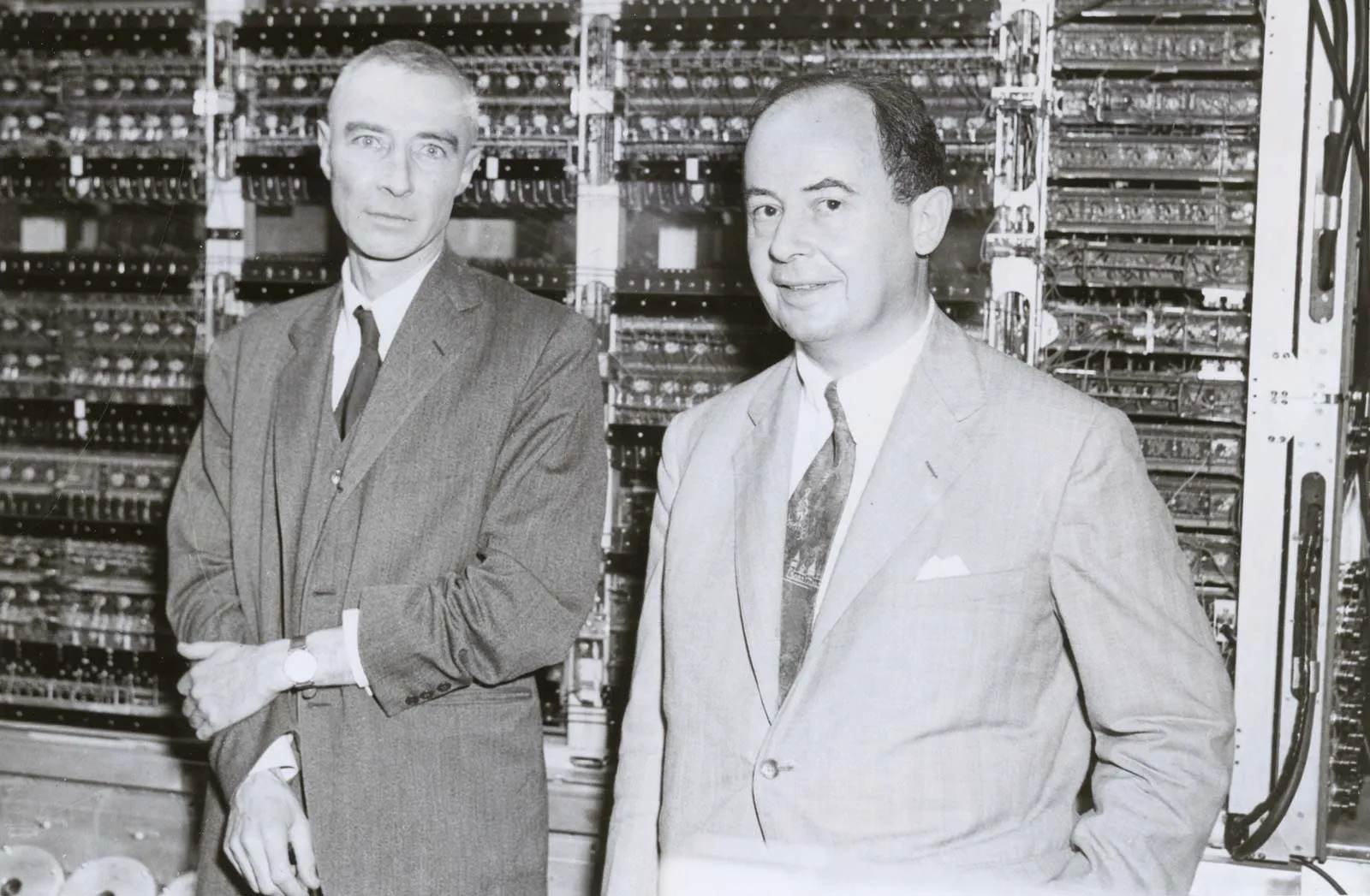

For those less interested in blind consumption, postwar America’s rapid ascent was stultifying, and Postman’s Depression-era restlessness only intensified. The Beat movement, whose poetry and fiction was hellbent on expressing the alienation and struggle for some kind of spiritual connection in a conformist, consumerist society, would dive two-footed into a fomenting subculture, documenting its coast-to-coast romps through mythopoetic, bebop-infused language that flowed out as a sort of listicle for more primal, kinetic experiences—jazz clubs, dive bars, soda pop, fast cars. In California—the land the atom bomb built—these confluences found footing in the growing netherworld of Assemblage.

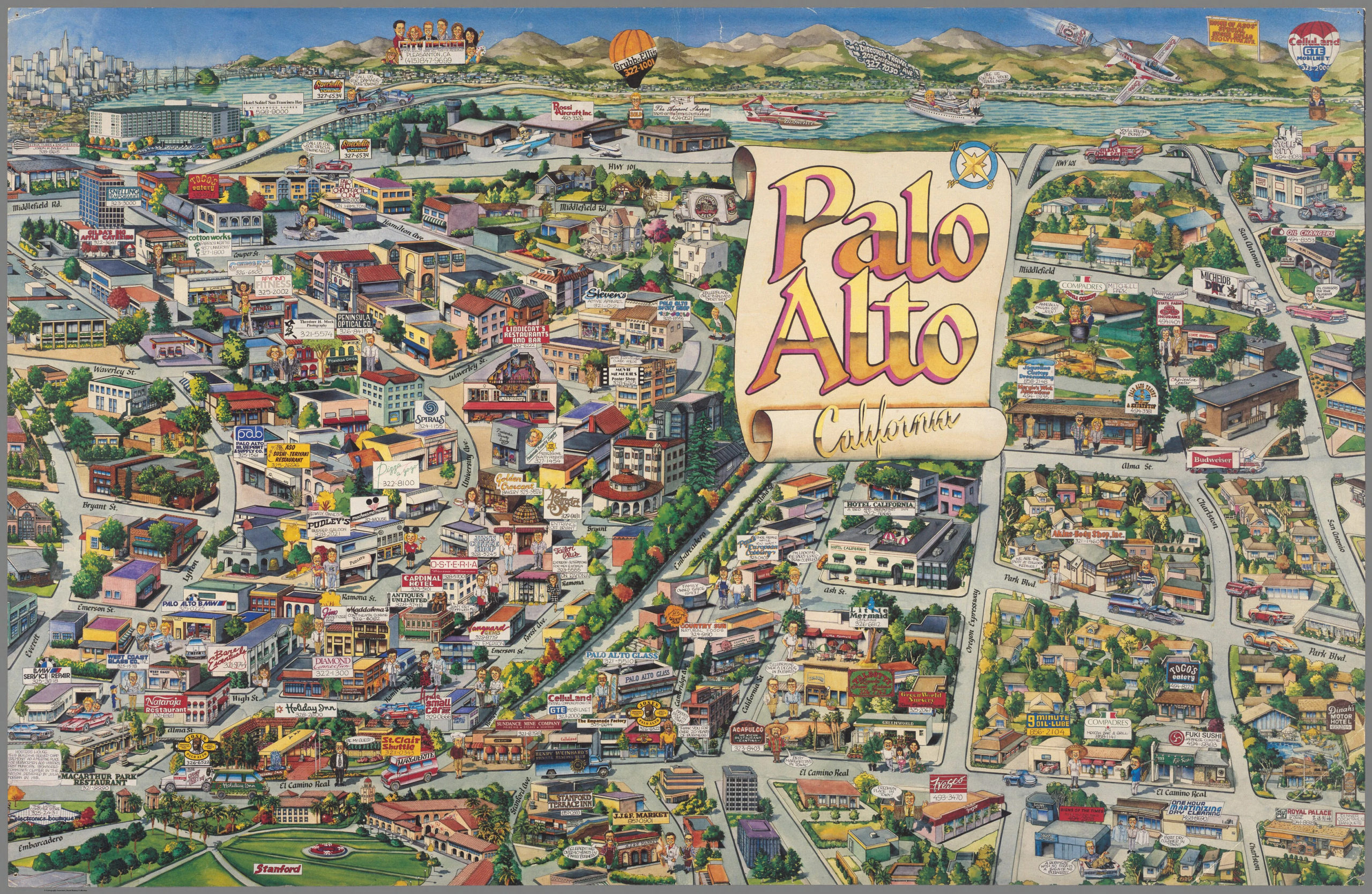

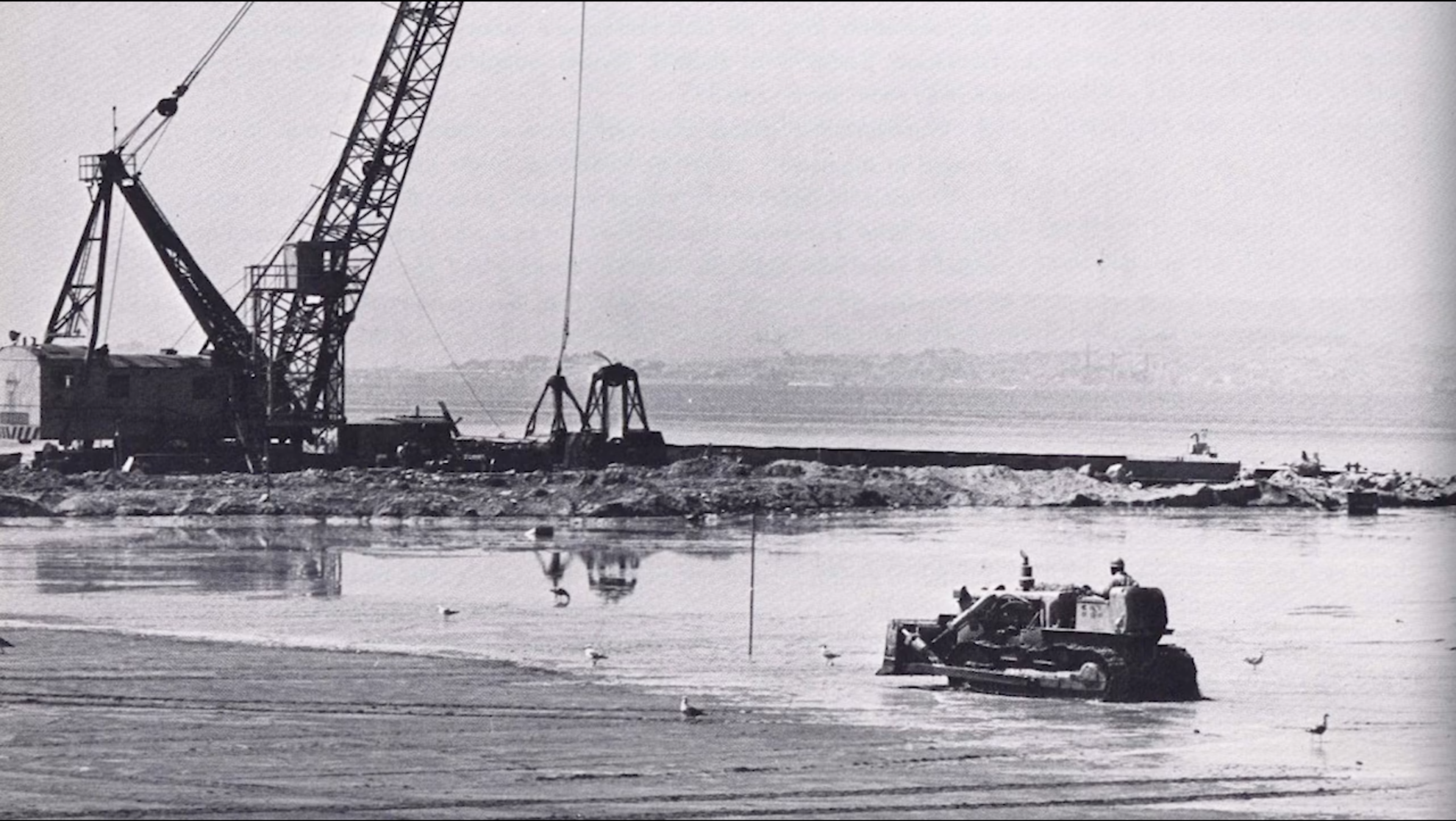

Perhaps buoyed by its victory over the Axis powers, the United States had shed the baggage of its Anglo-European inheritance like a kid freshly 18 handed a new set of car keys. Just blow. As the ‘50s gave way to the ‘60s, American art grew increasingly self-referential. Consumer products, popular culture, and—its seductive shadow—outlaw culture, were now prime subject matter for artists everywhere invigorated by these high-low confrontations. Between 1954 and 1963, Ruscha too sharpened his attention to everyday objects, like signage and roadside architecture, through his almost compulsive road trips. Relentlessly documenting his experiences in drawings, jottings, and photographs, he worked toward a representation of the vernacular of the American West, one that was defined—from landscape to marketing copy—by spareness.

In 1961, Ruscha embarked on a month-long tour of Europe. He photographed everything that grabbed his attention. Here was an American artist not as vassal but as tourist with a camera, merely remarking how, say, European speed limit signs were circular rather than square, how their cars too were rounded where Detroit’s were rectilinear. His profile began to rise around this time, thanks to works like 3223 Division (39’ Ford) from 1960, 5 Cents and Actual Size from 1962, and his participation the same year in key showings of the burgeoning West Coast and Pop art scenes—specifically Walter Hopps’s shows at the Ferus Gallery on La Cienega Blvd. and “New Paintings of Common Objects” at the Pasadena Art Museum. But 1963 is the year of Ruscha’s ascendancy.

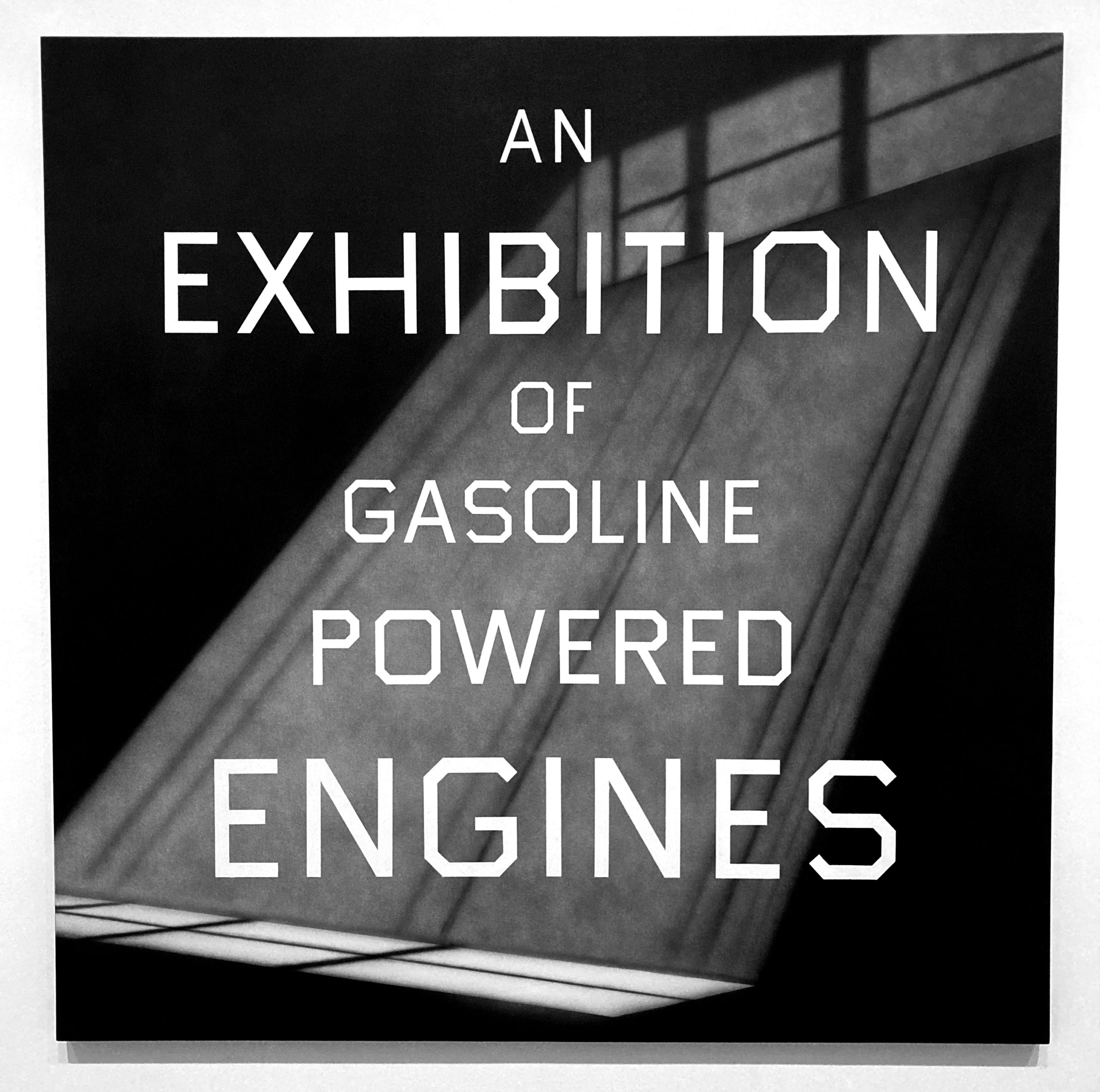

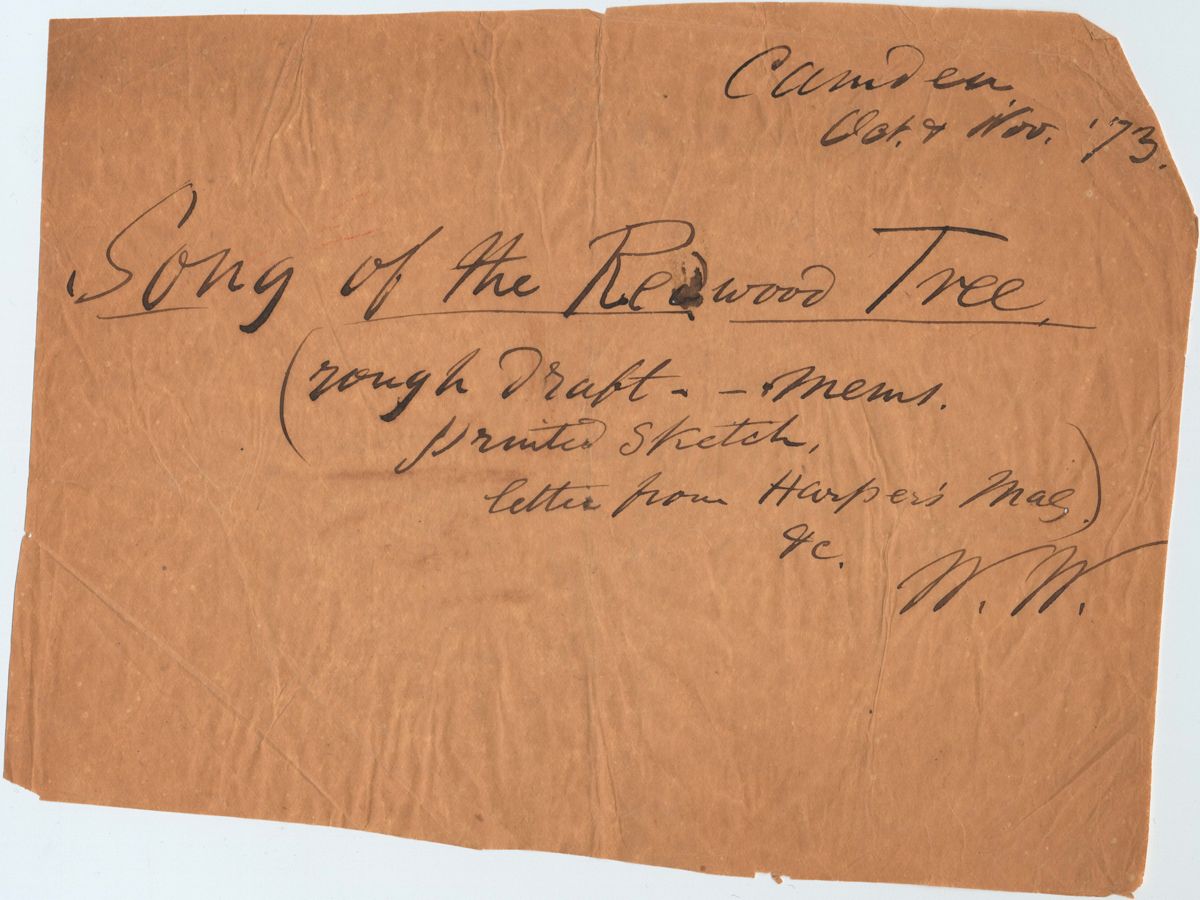

In ‘63 alone, Esquire would publish two of the New Journalism’s seminal texts: Terry Southern’s “Twirlin’ at Ole Miss,” a jocular exploration of racial tensions in the South under the cloak of a college baton-twirling competition; and Tom Wolfe’s “Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby,” a journey into Southern California’s Kustom Kulture—hot rods, tattoos, and masterful metal flake paint jobs (a movement that had seeped into Ruscha’s world through the works of peer Billy Al Bengston). Dennis Hopper, one foot in the Method world of James Dean and Marlon Brando, another in the exploding West Coast art scene, would hit the road with his 35mm Nikon and capture everything from Hells Angels at a diner to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March on Washington. And Ruscha, having traveled up and down Route 66 between Oklahoma City and LA for years to visit his parents, would publish arguably the first modern artist book: Twentysix Gasoline Stations. Twenty-six (because he liked the sound of the words) stark, black-and-white photographs of service stations from Los Angeles to OKC to Groom, Texas, plainly captioned with name and location, granting the work a “factual kind of Army-Navy data look,” as Ruscha described it. According to Johanna Drucker in The Century of Artists’ Books, the photographs “combined the literalness of pop art with the minimalist [ironies] of repetitive sequencing”; most importantly, however, they set the blueprint for his most famous works: the Standard Station series.

Relentlessly documenting his experiences in drawings, jottings, and photographs, he worked toward a representation of the vernacular of the American West, one that was defined—from landscape to marketing copy—by spareness.

Debuting in 1963 with Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, the Standard Station series depicts, in a range of flat, impeccable colors, a Standard gasoline station that slashes the canvas diagonally in half through a dramatic use of perspective. They are large, and disorienting when viewed at scale. “It has to be called an icon,” Ruscha deadpanned to Paul Karlstrom in the early 1980s, speaking to the word’s Christian meaning. “That gas station had a polished newness that I just had to paint.” It’s a series he would continue to paint in endless variations until 2011, one that helped cement Pop art as the dominant art movement of the moment, and further launch California (specifically Los Angeles) into the artistic mainstream. Having introduced his stark, Soviet Constructivist-inspired use of perspective in 1964 with Norm’s, La Cienega, On Fire—which set his all-night hangout aflame—the Standard Station paintings and screenprints encapsulate the American West as a tale of scale, migration, and heavy industry, all at once.

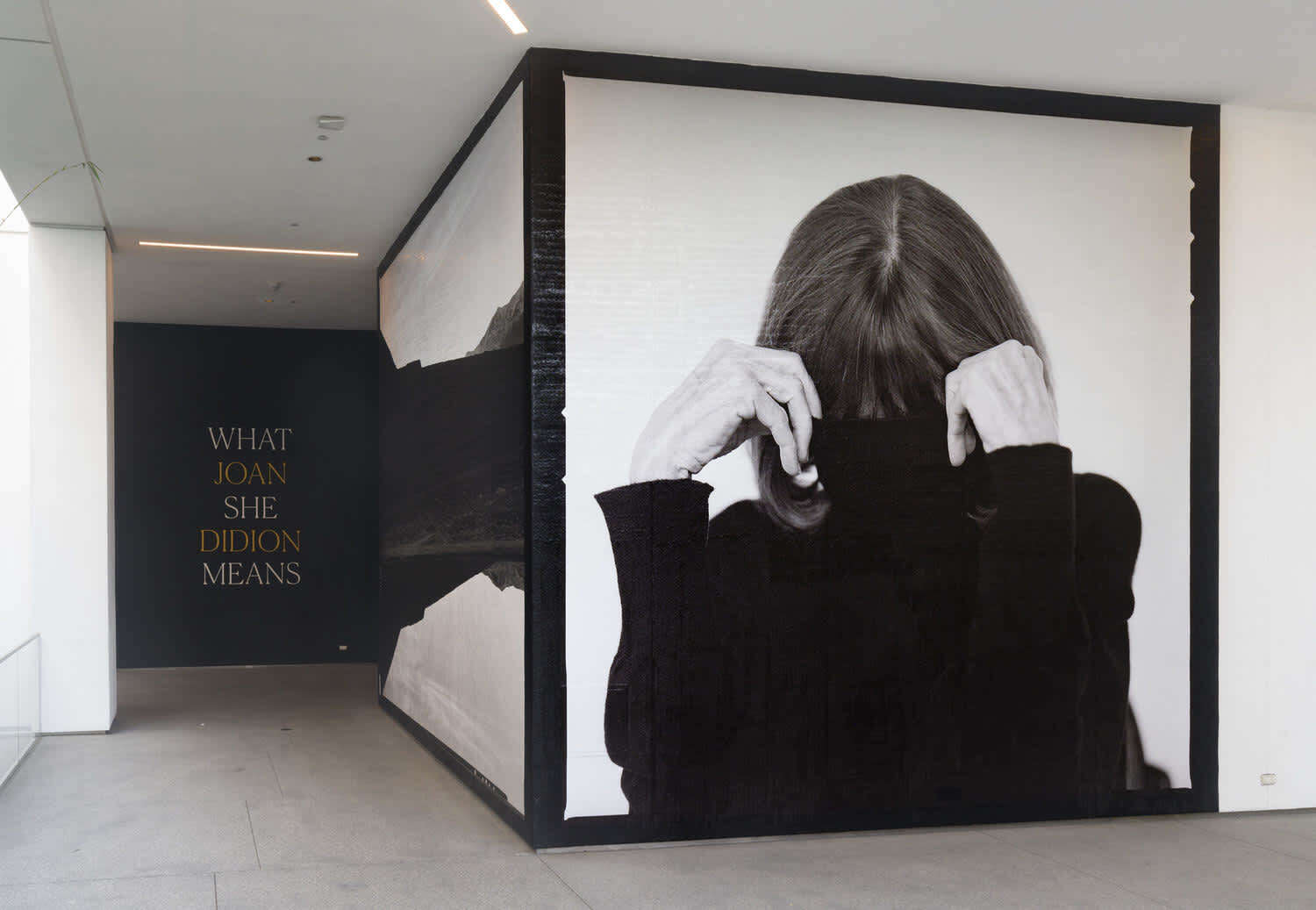

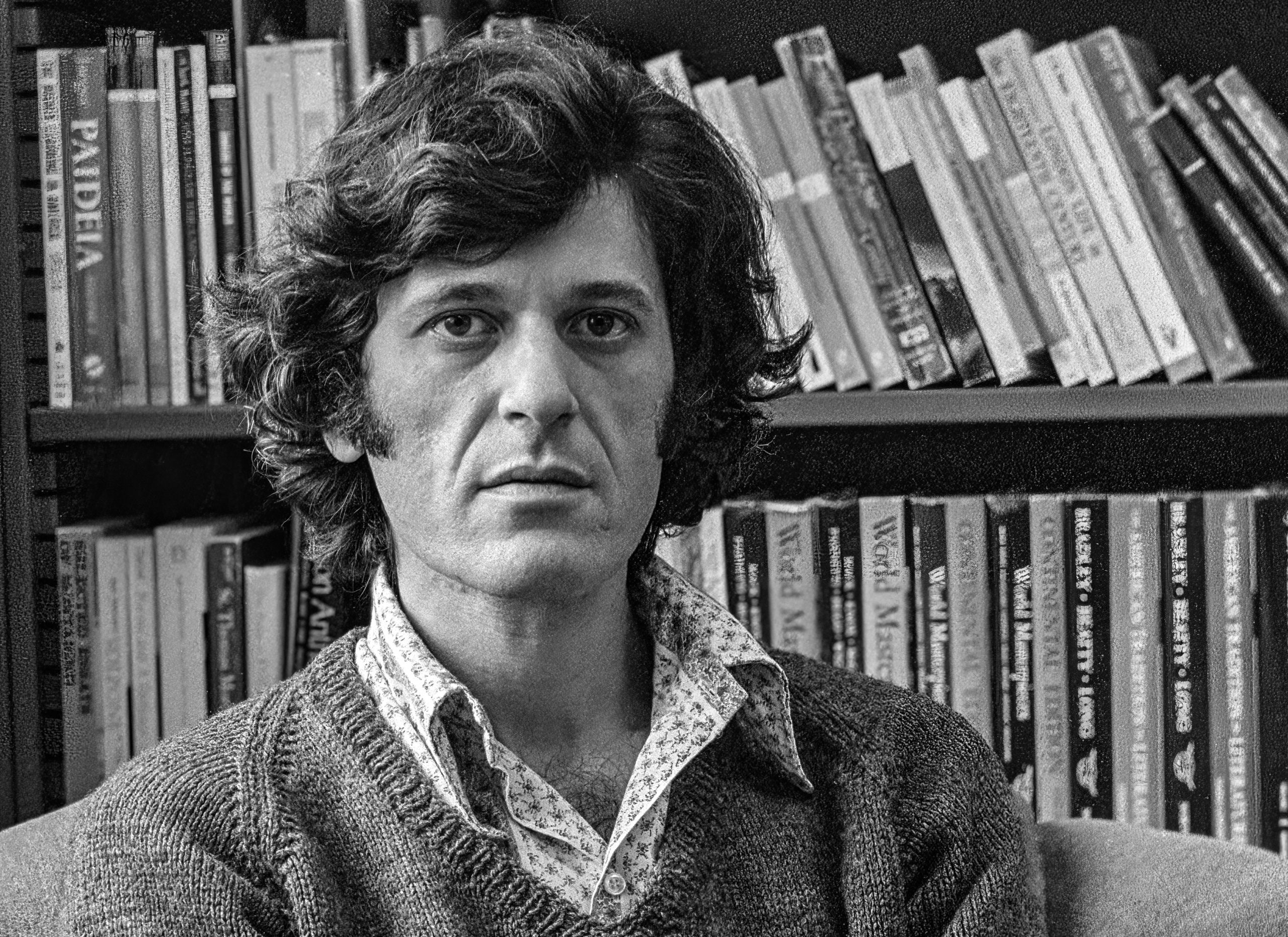

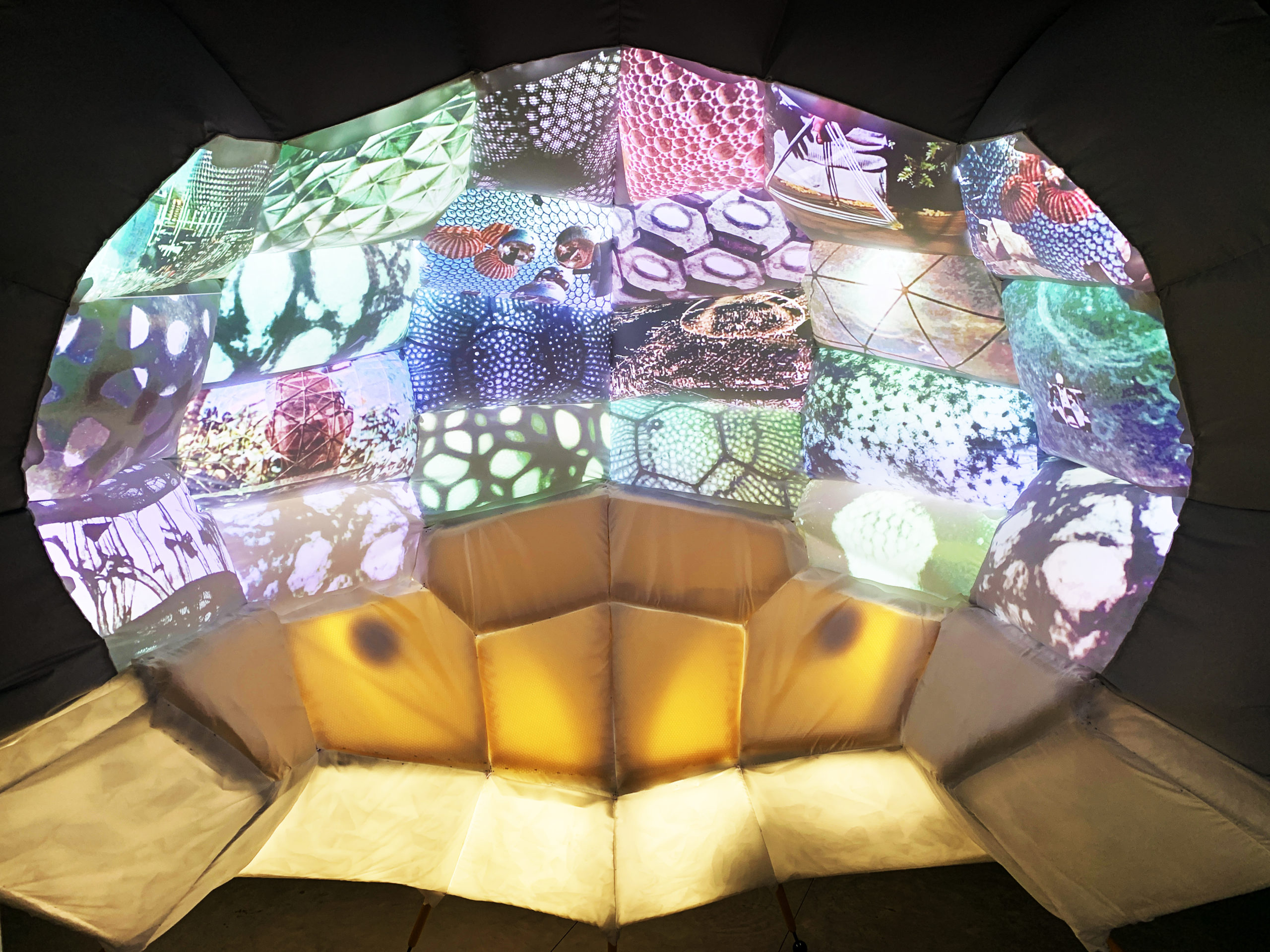

Ruscha’s six-decade (and counting) career of depicting the defining features of modern American society—consumerism, pop culture, the commercial landscape, the American English language—was on display in “ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN,” his first cross-media retrospective in over twenty years. Starting out at the Museum of Modern Art New York before heading to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “NOW THEN” featured over 200 works—including paintings, photographs, drawings, and artist books—to spotlight Ruscha’s understated yet indefatigable dynamism.

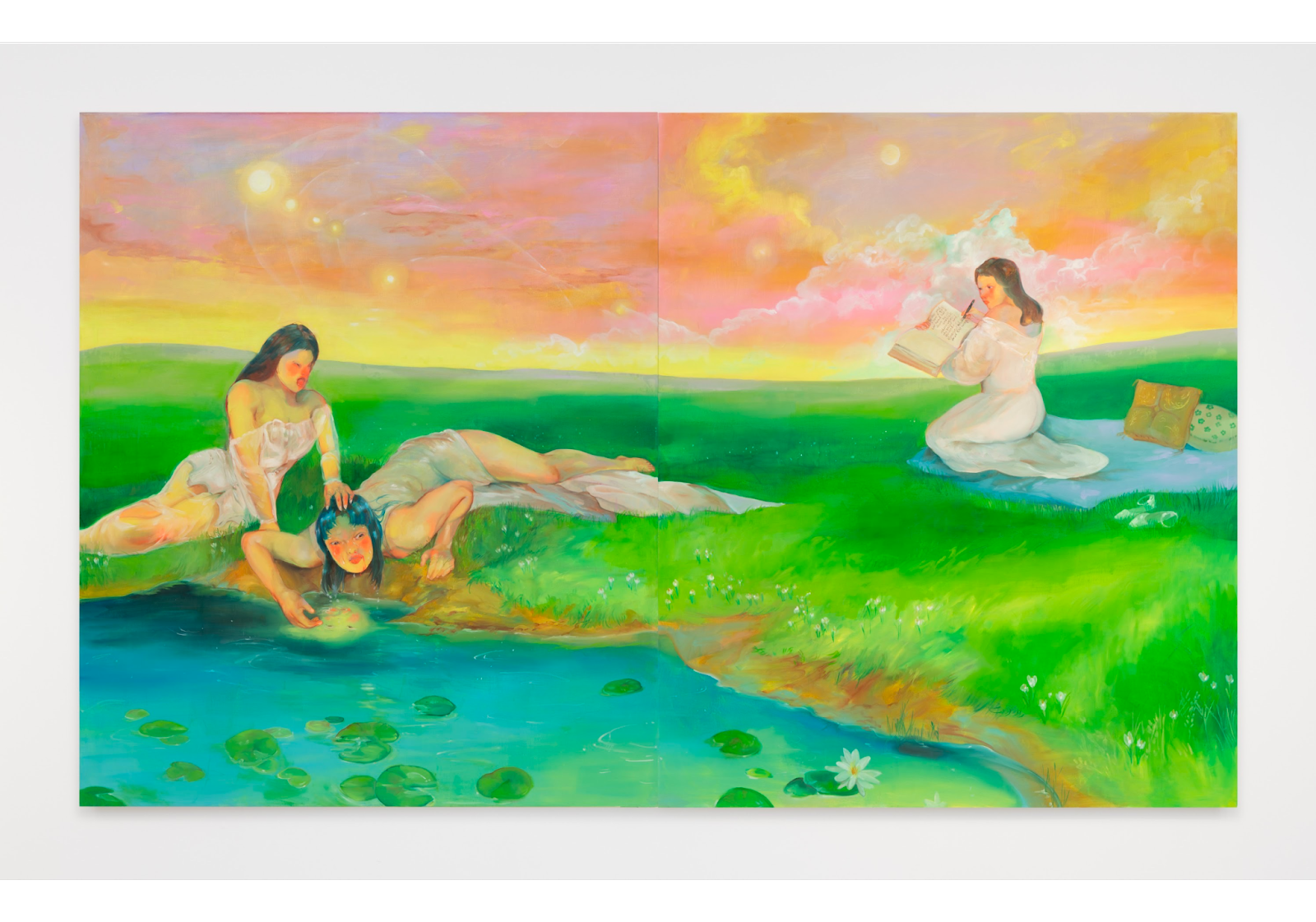

Pairing mediums as diverse as gunpowder, chocolate, and blood with evocatively droll titles like “Two Sheets with Whiskey Stains,” “Pepto Caviar Hollywood,” and “I’ll be getting out soon and I haven’t forgotten your testimony put me in here,” Ruscha’s body of work captures something quintessential about the American experience that is almost as intangible as electricity itself, as full of discordant vitality as Frank Chambers. His pieces are both a part of and a comment on the postwar explosion, a heady time when even the limits imposed by the laws of nature seemed no match for the boundless enthusiasms of American capitalism. They are also snapshots of that moment when the United States—and particularly California—each came into their own, the crest of a vital, if only momentary, monoculture.

And yet Ruscha, whose life seems to embody and incriminate something terminal about the American West, filters his America through a lens only California—with its wicked ironies—could provide. In his landmark study, The Invention of the Western Film, Scott Simmon identifies the West’s long-held cruel politics of space: “Empty land is there for the taking.” Ruscha sets his darkly comic vignettes in a setting imbued with that kind of force, and he pokes fun at it, at the absurdity of it.

In 1964 he paints Hurting the Word Radio (#2), where he disfigures letters with metal calipers on a sky blue background reminiscent of a Technicolor western. In 1967 he publishes Royal Road Test, a forensic investigation of a typewriter destroyed along Highway 91, 122 miles southwest of Las Vegas. In 1973 he paints the word EVIL in his own blood on a blank, crimson background. Empty space always appears stalked by violence. Intrigued by oblique perspectives and ironic juxtapositions, he is almost preternaturally disposed to dialectical expression, to identifying, in direct imagery, the contradictions invigorating the land abutting the Pacific. He’s called the brilliant sunsets of the West “anonymous backdrops for the drama of words.” Words. Perhaps, having lived through the ballooning century of stuff, Ruscha’s secret message—the key to that tattered, traveling copy of Popular Western hidden throughout his works—is this: “Words live in a world of no size.”

ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN

Ran April 7th - October 6th, 2024

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

5905 Wilshire Blvd

Los Angeles, CA 90036