IF, AS MARSHALL MCLUHAN OBSERVED in the mid 20th century, “the wheel is an extension of the foot, the book is an extension of the eye, [and] clothing, an extension of the skin,” then what, in the early 21st century, is the nature of our relationship to our most intimate contemporary instrument, the computer? Rather than an extension of one part of ourselves, the “personal” computer (desktop, laptop, tablet, phone) feels like nothing less than an extension of our whole selves.

While the pernicious side effects of social media are being scrutinized in what passes for public conversation, the computer itself has assumed a more concealed state, touching everything we do, but conceived as an incredibly routinized, almost banal, part of our everyday lives. If, however, the computer is viewed not as ordinary, but extraordinary, something beyond a tool, its impacts on our thinking and acting begin to reveal their true nature. Although commonly misappropriated as a mere “tool,” a key difference to note in this reframing is that the computer is in actuality not in the same category of technology as the wheel or the written word, which can both be conceptualized as tools since they serve very specific functions through very specific means. Rather, the computer is a collection of various tools, or, a machine. This condition alone creates a tangle of questions and implications in any attempt to understand not only how it is used, but how its use affects us.

Marx’s critical understanding of the emergent machines of his time, from looms to locomotives, reflects the relative simplicity of the mechanical assemblages themselves, especially when compared to the computer; nonetheless, his diagnosis of their effects is still relevant today:

In handicrafts and manufacture, the worker makes use of a tool; in the factory, the machine makes use of him. There the movements of the instrument of labor proceed from him, here it is the movements of the machine that he must follow. In manufacture the workers are the parts of a living mechanism. In the factory we have a lifeless mechanism which is independent of the workers, who are incorporated into it as its living appendages.

Prior to Capital, the machines were understood as nothing more than a sequential evolution of simple tools, at most combined in marginally more complex ways. Conversely, Marx observed that the difference between a tool and a machine is much more than a new arrangement of existing hardware; instead, it is a fundamental reorientation of the relationship between ourselves and the material world around us. In other words, what we work on works on us.

Isolated to a contextual use inside the factory, the machine that Marx scrutinized affected a small amount of the population compared to today’s ubiquitous, “personal” computers and devices. An important translation of this idea to modern life, though he was writing exactly one century later, is McLuhan’s exponential thesis that “Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication.” While 19th century machines were imposingly physical, the ones of McLuhan’s era were increasingly psychological; today of course, ours are almost entirely digital.

More so than the unending abundance of “content” communicated by tech companies, the computer and the rapid acceleration of its transmission has drastically transformed our collective understanding of ourselves and society around us. As a tangential footnote, one recalls Hannah Arendt, in The Human Condition (1958), remarking on the speed-induced warping of our scalar perception in a newly globalized world:

The fact that the decisive shrinkage of the earth was the consequence of the invention of the airplane, that is, of leaving the surface of the earth altogether, is like a symbol for the general phenomenon that any decrease of terrestrial distance can be won only at the price of putting a decisive distance between man and earth, of alienating man from his immediate earthly surroundings.

Though not placing us “above the earth” per se, our world of the personal-digital inversely removes us, even if only cognitively, from the material world directly around us.

Notwithstanding the rapid evolution of other technologies from the 18th century onward, there can be little doubt that we live in a thoroughly digitized world, our daily experiences are mediated as deeply, if not as widely, through the digital as the material. In many cases, the two are indistinguishable; most of the physical material we interact with houses the infrastructure necessary to execute the various digital interfaces consuming our attention. But while all white-collar workers, and even most workers in the service industries, rely on computers to complete their tasks—add that children are nonchalantly handed tablets as a means of learning and distraction almost from the womb—there exists a group of practitioners who have a distinct form of material knowledge that is especially susceptible to the powerful forces of technological rapidity: artists and designers. While such epistemology has become mainstream, with scientists and writers stumbling upon the idea of learning outside the brain, this form of knowing is one that artists and designers have been privy to for centuries. No modern treatise depicts this reality better than chemist-turned-philosopher Michael Polanyi’s The Tacit Dimension (1966).

Tacit knowledge is less concerned with proposing a problem a priori, which seeks a solution that neatly fits within the original boundaries—a framework which our digital society so heavily relies on. […] Maintaining that these other spheres have as much, if not more, to offer society than science and technology, Polanyi draws parallels between the sciences and the arts, in that both can engage us in active seeking and discovery.

Born in Hungary in 1891, Michael Polanyi pursued a polymathic career the like of which is now almost inconceivable. Initially developing several novel experiments and theories in various branches of physical chemistry, he worked in government, contributed to economic theory and eventually, through a chairship in the social sciences at the University of Manchester, arrived at philosophy. In 1962, Polanyi presented a series of lectures at Yale University, marking his transition from a decorated career in science to one in philosophy. Through an intimate understanding of scientific knowledge and discovery, Polanyi offered the insight at the heart of his preceding work, Personal Knowledge (1958): “We can know more than we can tell.”

In The Tacit Dimension, Polanyi spends less time focusing on what science and technology bring to our understanding of knowledge, than on how artists and other “creative” practitioners already work through similar ontological processes by means of their own special forms of making and thinking.

Rejecting the simplistic version of positivism (the belief that all knowledge can only be understood, and verified, through the “facts” of the experienced world), Polanyi instead asserted the clout of literature, the fine arts, and other “non-scientific” pursuits, emphasizing “the pressure exercised by literary and artistic circles is notorious.” In other words, while science and technology were continually creeping into all parts of society, Polanyi instead sought the arts as a place for better understanding our deepest forms of knowing. In chapter three, “Society of Explorers,” Polanyi meditates on the creative acts of seeking and recognizing problems:

Yet, looking forward before the event, the act of discovery appears personal and indeterminate. It starts with the solitary intimations of a problem, of bits and pieces here and there which seem to offer clues to something hidden. They look like fragments of a yet unknown coherent whole. This tentative vision must turn into a personal obsession; for a problem that does not worry us is no problem: there is no drive in it, it does not exist. This obsession, which spurs and guides us, is about something that no one can tell: its content is indefinable, indeterminate, strictly personal.

While some of these “bits and pieces” might have origins in familiar material, Polanyi argues that they are pointing toward that which is not yet known. Further, the intimation of a problem is a significant act in and of itself. If taken as a basis not only for knowing but also for acting and subsequently being, this assumption has far reaching consequences. Polanyi continues:

Indeed, the process by which it will be brought to light will be acknowledged as a discovery precisely because it could not have been achieved by any persistence in applying explicit rules given to fact. The true discoverer will be acclaimed for the daring feat of his imagination, which crosses uncharted seas of possible thought.

Tacit knowledge is less concerned with proposing a problem a priori, which seeks a solution that neatly fits within the original boundaries—a framework which our digital society so heavily relies on. In Polanyi’s view, artists are more akin to the explorers who set out with some understanding of where they might be going, content to encounter the unexpected, folding those unexpected things into the very direction and processes of the expedition itself. For the explorer, this might be never-before seen flora and fauna taking precedence over the original aims of material extraction; for the artist, an accidental smudge on the canvas can turn into the focus of the piece itself.

Maintaining that these other spheres have as much, if not more, to offer society than science and technology, Polanyi draws parallels between the sciences and the arts, in that both can engage us in active seeking and discovery. Because of its dependence on binary functions, in this context it is nearly impossible to make a “mistake” on a computer, begging the question: Are there any spaces of truly free discovery in the digitized world?

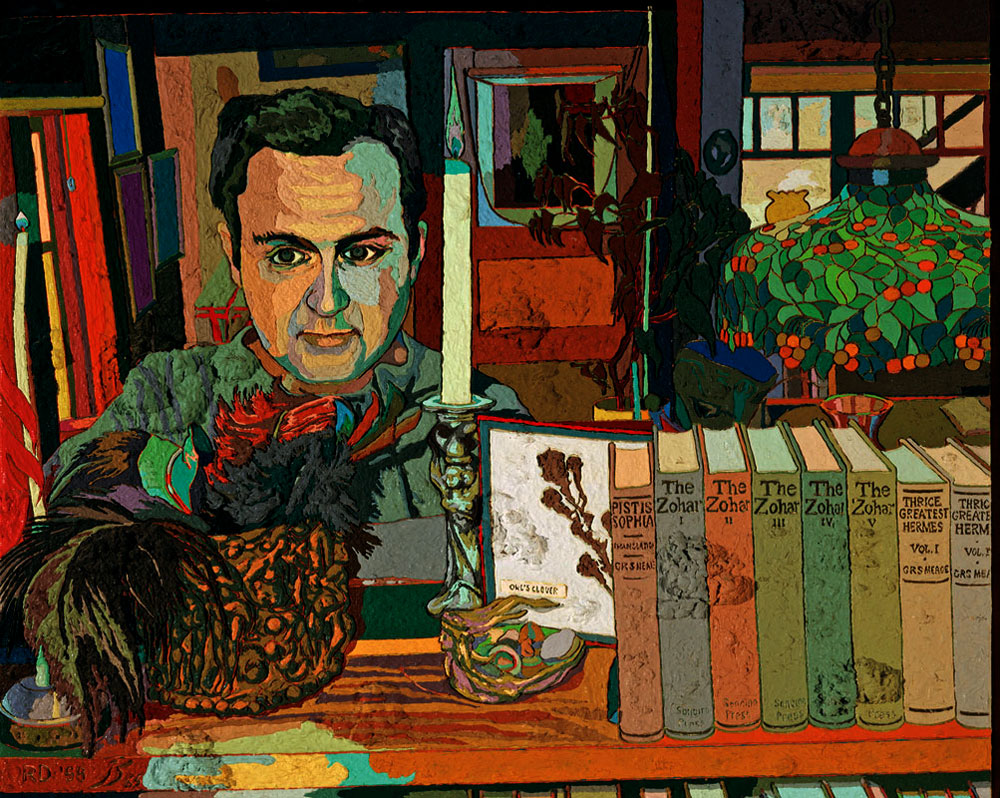

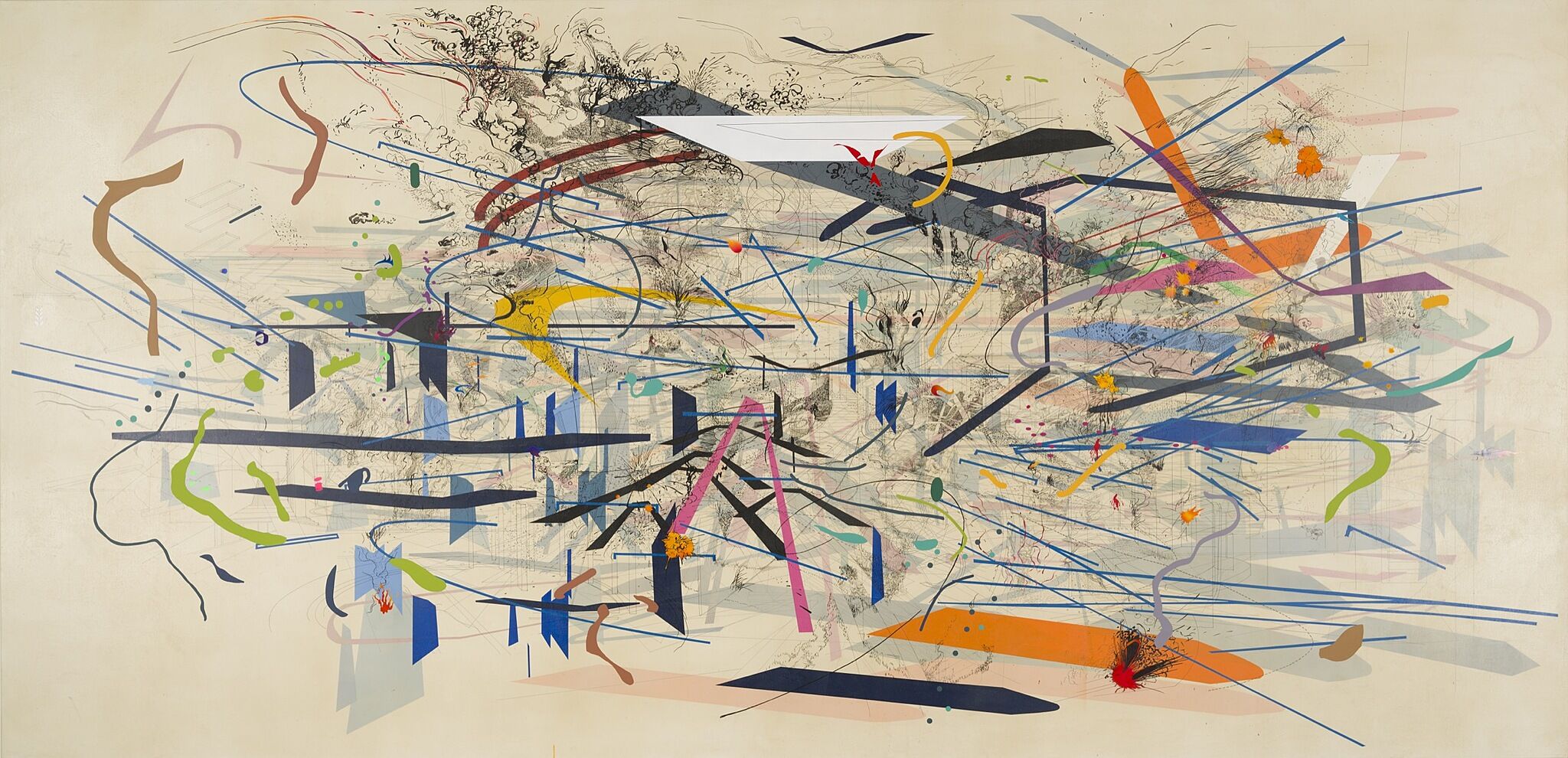

On display at a recent mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum, Julie Mehretu’s gargantuan canvases—and her deliberately slow exploration of them—offer a portrait of an artist who has developed a creative process that is reliant on, but definitively not subservient to, the digital. Included in the show are videos of Mehretu’s meticulous construction of the paintings, not dissimilar in scale to muralists plotting their “canvases” on the sides of urban street-walls. Building upon layer after layer of digitally transcribed elements of architecture in pieces like Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts) (2012), the collision of existing conditions generates spaces and forms upon which the artist can project their own vision into the sampled background.

More concretely, Mehretu’s most recent work, such as Haka (and Riot) (2019), begins with photographs of migration detention camps which, while scaled to sizes well beyond immediate recognition, still generate a willful and incredibly rich examination of the crisis. This “opacity,” as described by Mehretu—or an unwillingness to explicitly reproduce the photographs themselves and instead utilize them as a stratum for further exploration—subverts much of the precisely transmitted information technology is keen on piping to its users. Contrasted by the digitized world around us, with its promise of “radical” transparency through unfettered access to unlimited content, Mehretu’s deliberate and intentional winnowing of such inputs is a model of more than just an alternative mode of artistic practice: It is a re-orientation of daily life.

As a practicing architect who also writes and draws, I have taken inspiration from Mehretu’s formal expression, as well as her slow dance with technology, a process which offers a necessary pause from the speed at which information is both ingested and shared. Herbert Marcuse suggests what creative acts might look like outside the hegemonic nature of imposed technology:

The tension between the ‘is’ and the ‘ought,’ between essence and appearance, potentiality and actuality … permeates the two-dimensional universe of discourse which is the universe of critical, abstract thought. The two dimensions are antagonistic to each other; the reality partakes of both of them, and the dialectical concepts develop the real contradictions.

In this case, the “is” is the concrete, instructive reality of the act, or the direct subject matter. Conversely, the “ought” is the aspirational or suggestive character. A contradiction inherent in drawings made exclusively through the computer, unlike those Mehretu creates, is that although they can achieve hyper three-dimensional qualities on screen, in some cases even mimicking something closer to four-dimensional space because of the accelerated spatial and temporal viewpoints privileged to the user, the resultant drawing is a “one-dimensional” product, only indicating what “is,” and abdicating any notion of what “ought” to be.

My drawings, on the other hand, seek to avoid engagement with these types of flat lines, the likes of which constitute the one-dimensional quality Marcuse is wary of. This happens primarily through the use of manual means, the most simple and direct way to disengage with technology. Even though I use a projector as an underlay to trace source material, this in itself subverts the speed of the digital, since it would be much faster not only to avoid translating the material through a projector, but also to draw the lines within the computer itself. Instead, expanding the “distance” between the video and the screen creates an opportunity to find something that I might not quite understand, or, in Polanyi’s words, know but can’t say.

My drawings are typically of the world around me, seen through the slowing down, or the expansion, of various patterns of movement. Both the material constraints—that of paper rather than screen—and the intentional deceleration of my experience of the content itself expand my opportunities for new discoveries and accidental occurrences. Drawing in this form can also be seen in terms of Marcuse’s “Great Refusal,” a direct rejection of that which is.

While it’s easy to admire a virtuosic talent like Mehretu, the odds are that most of us identify more with Marx’s “Struggle Between Worker and Machine” than with the life of an internationally acclaimed artist, whose honors include a Berlin Prize and a MacArthur Fellowship. Digital nihilism appears like a fulfillment of the utopian promises of tech, but the reality is a workforce—and a population at large—being consumed by the promised technology, like the machines of Marx’s time: an absolute grip on our attention, the commodification of data, and a surveillance of the habits that create our identities.

For the most innovative cultivators of our material world, artists, the picture hardly feels more hopeful. Instead of spending our days crafting the next canvas, or contemplating new media to use, most of us must struggle to fit these moments into the specialized working lives that allow us to support independent creative pursuits. Even if we are able to do so, the proliferating digital landscape means that with each piece of new technology or software, the attention required to manage it consumes yet more of our mental bandwidth, leaving artistic practice feeling even more like an afterthought.

Although the digital revolution has led to an increase in efficiency of production for artists and designers, whether working for themselves or someone else, it has also profoundly distanced them from their actual productions. Complicating this remoteness from the “craft of making” is a corporitizing of the various technologies and tools used in so-called creative industries. Just as the 19th century factory worker was alienated from the means of production because the machinery was owned by someone else, so too the artist is alienated from the new-found digital means of production. Today, a handful of colossal corporations develop and own key pieces of software, thus enabling them to dictate the precise nature of how designers do their work.

The fact is, for many of us avoiding the computer simply isn’t an option—it’s too intertwined with every aspect of our lives, not just in the ways we communicate but also in how we see and act. It’s quite tempting to romanticize an age of grand ideas and narratives living through paper, a comforting form of bookish escapism. But it’s too late to pretend we’re still living in a world held exclusively by the machinery of Gutenburg.

When these issues are translated to society at large, from how news media has become thoroughly atomized to how social media is affecting the development of social patterns in young people, claiming any source of agency feels nearly impossible. One thing that is possible, within our agency, is to become more careful observers, more aware of how we can slow dance with the machine, not only following, but dictating the pace ourselves. If we seek to make the computer an extension of us, rather than we an extension of it, we must continually examine our relationship, determining, for ourselves, where we fit between the material and digital. The meaning is the medium.