[drop-cap]

In July 1975, Ed Ruscha recalled a dream in which he drove out west and moved into an apartment in Los Angeles. “I pulled into Hollywood off a palm-lined street and tucked my car under an apartment house overhang carport whose front end featured 3-D show-card slash script letters that spelled out ‘SWANK.’” It didn’t happen exactly that way, but the Nebraska-born, Oklahoma City-bred artist did, like many design practitioners working in the mid-1950s, move to Los Angeles and find a creative Mecca. This westward push led to the first survey exhibition of Pop art, held at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962. Curated by Walter Hopps, “New Paintings of Common Objects” featured Ruscha as well as fellow canonical Pop artists Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

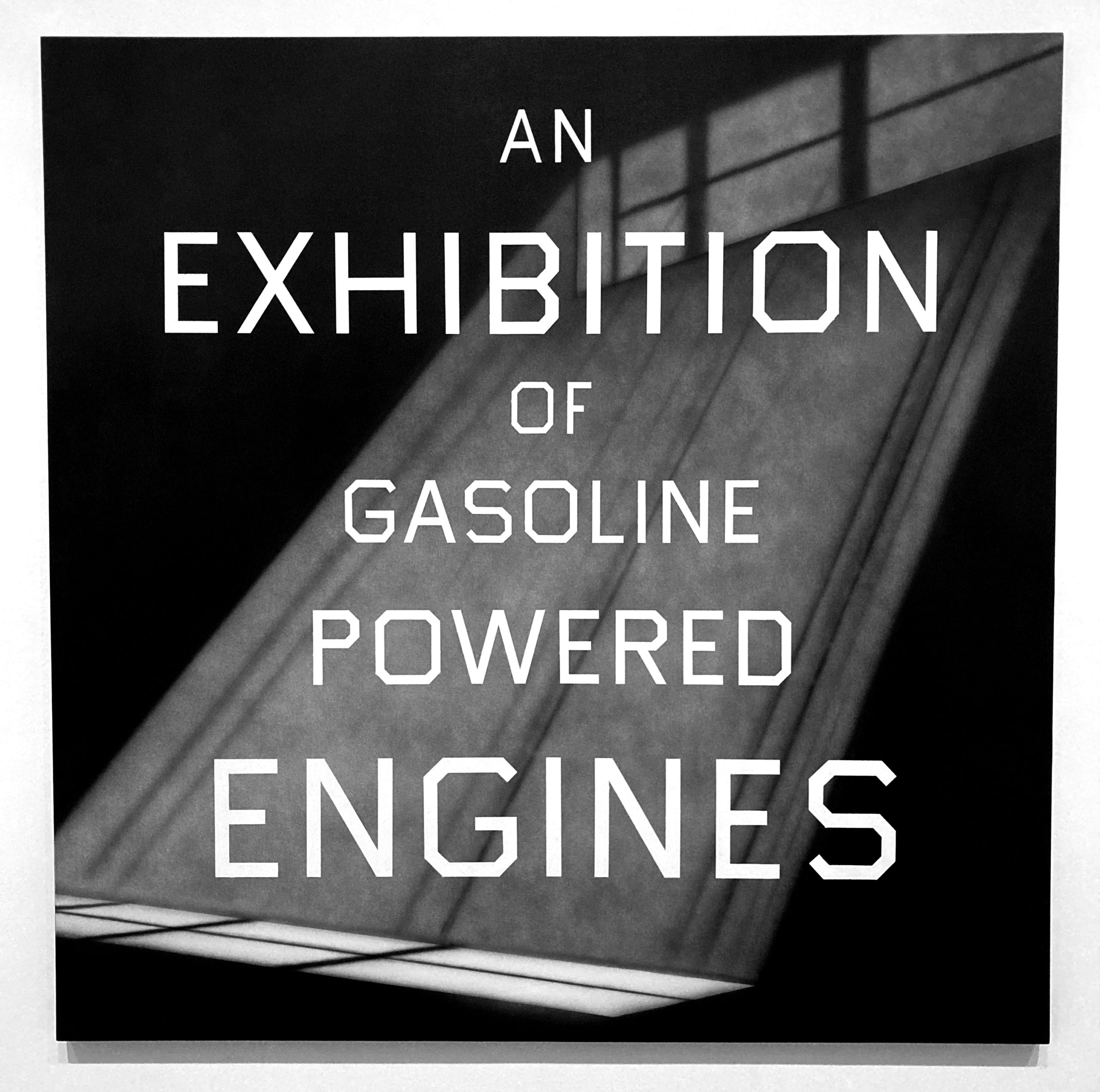

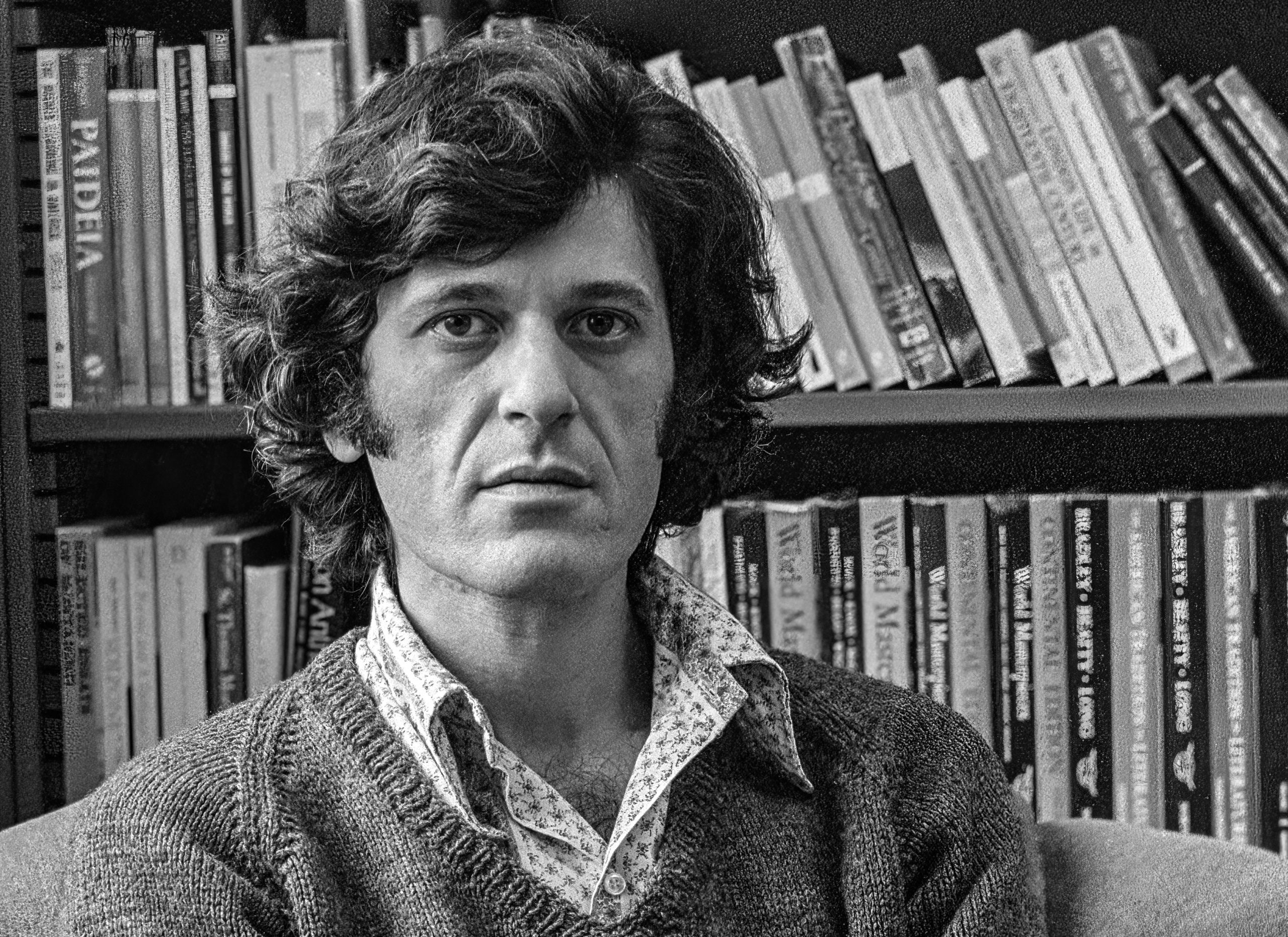

Ruscha’s attentiveness to more common architecture is evident in his photographic documentation and painted renderings of domestic and commercial structures across the Western United States. When British architectural historian Reyner Banham interviewed Ruscha in his 1972 travel guide to the city, Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, the artist suggested tourists visit its gas stations.

From the exuberant signage to the garage underneath the house, it is evident, even without Ruscha’s naming it, that the apartment the artist settles into in his dream is one of the city’s most easily recognizable architectural achievements: the dingbat.

The apartment complexes can range in style from Tiki to Mansard to Googie but they always reference the fantastic or the far flung. The wide range of styles that dingbat architecture draws from seems to give credence to Frank Lloyd Wright’s tongue-in-cheek theory that if the earth was tipped, “everything loose [would] land in Los Angeles.”

In the mythology of the dingbat, Banham is effectively responsible for popularizing the term. Yet few people, even the hundreds of thousands who inhabit these complexes, realize this architectural species has a name. The style emerged in Southern California in the early 1950s and reached its peak in the late 1950s and 1960s. In his 1971 dissection of the city, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Banham distinguishes the style as a two-story wooden box structure glazed in stucco that fills any lot it is placed on. With these “boxes” all the interest is dedicated to its façade, while its other three sides are often left blank.

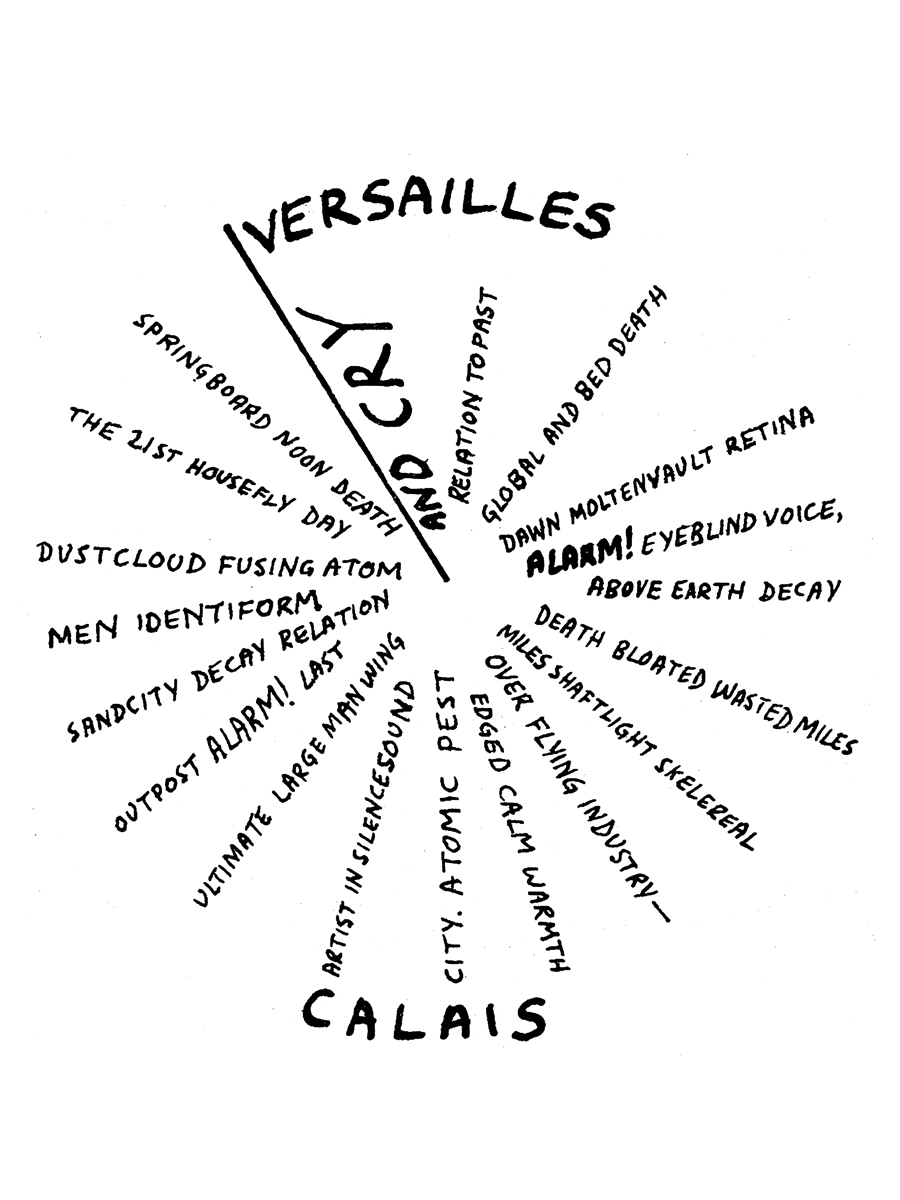

A near requirement of the dingbat type is a fanciful name accompanied by ornate typographic signage visible from the street. The names often evoke exotic places or edifices much grander than their simple construction would suggest. Names such as “Vista Capri” (3906 Inglewood Boulevard) and “La Traviata” (1138 Euclid Street) are followed by superimposed designs meant to fortify the evocation. The apartment complexes can range in style from Tiki to Mansard to Googie but they always reference the fantastic or the far flung. The wide range of styles that dingbat architecture draws from seems to give credence to Frank Lloyd Wright’s tongue-in-cheek theory that if the earth was tipped, “everything loose [would] land in Los Angeles.”

It is unsurprising that the name and typography of an apartment complex would feature prominently in the dreams of an artist who started out as a draftsman for an advertising agency—not unlike his fellows, Warhol and Lichtenstein. “SWANK” in particular seems to speak directly to dingbat architecture and its faux-luxe posturing, hankering as it does to impress us. In a 2015 interview with Jonathan Griffin, the artist mentioned that what attracted him most to Los Angeles was its “swank mentality” and “tropical flash.”

It’s understandable that people generally dislike the dingbat for its particular brand of kitsch, full of embellishments and superfluous ornamentation. But Ruscha didn’t perceive these traits negatively. In fact, the city’s sense of artifice and its particular predilection for ever-changing culture was what attracted him most.

Within this fast-paced environment, LA is notorious for its architectural turnover. Many of the dingbat’s one-story structures have been torn down to make room for larger occupancy three-story buildings. Several artists turned to documenting the architectural style precisely because of its impermanence, most notably by Ruscha in the 1960s, photographer Judy Fiskin in the 1980s, and more recently Lesley Marlene Siegel in the 1990s.

In Ruscha’s third artist book, Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), several dingbats are featured within the thirty-four photographs of apartment complexes. Each image is taken from the street, usually less than 100 feet from the structure. Ruscha held his camera, a Yaschica twin-lens reflex, at waist height and determined the shot by looking downward into a focusing screen. Ruscha’s photographs place us, the viewer, as if we were driving by in a car.

This symbiotic relationship between the dingbat and the car—an essential feature of all mid-century Los Angeles urban planning—is conveyed in the way Ruscha describes the experience of peering out the window in his dream: “As I looked out [...] I could see part of the letter ‘S’ together with the tail-end of my Ford Victoria hardtop convertible.” The typeface bleeds into the car’s design, fusing automobile and architecture.

John Chase argues that the dingbat type owes more to consumer products than to preceding architectural styles. Instead, Chase perceives the eccentric color combinations typical of dingbat apartments as an ode to the advertising and automobile industries. This aspect of the dingbat has prompted writers to associate the style with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s notion of the “decorated shed.” While studying the particular urban phenomenon of the Las Vegas Strip in the 1960s, Venturi and Brown coined the moniker to distinguish utilitarian buildings that rely on flashy signage or ornament to advertise what’s inside.

Despite the dingbat’s claim to foreign styles, its ornamentation locates it.

This reading would seem to suggest that the dingbat is a byproduct of mundane consumerism. However, despite their similar starting points, the dingbat’s walls speak more strongly of individualism than generic reproduction. Chase discusses the new precedence set by dingbat architecture in terms of experimentation in stucco. By streaking patterns through the material or adding aggregate and color to the plaster, the buildings are subtly distinguished, more craft-like than mass-produced.

The accompanying signage of each complex also alludes to its owner’s personal aesthetic. Each fantastical name acts as an identifier. At times the dingbat signs are simply street address numbers blown up in typographic fanfare. Despite the dingbat’s claim to foreign styles, its ornamentation locates it.

Unlike architectural styles that are characterized by specific exterior elements, the dingbat does not have a corresponding interior aesthetic. Dingbats, as rented spaces which alter according to the preferences of its rotating tenants, are ever-changing. Its interiors are best illustrated in Tamara Jenkins’s 1998 cult classic, Slums of Beverly Hills, where a Jewish family moves from one dingbat to the next, avoiding rent while pursuing social gain. The nomadic life of its tenants is conveyed by its near empty rooms.

But does the dingbat even have a future? The LA Forum held a competition in 2010 to imagine a 21st century form of “dingbat-ness” for the dated yet hardly old design. In lieu of preservation or restoration, the winning project, entitled “Microparcelization,” called outright for the type’s destruction. Microparcelization proposes to update the dingbat’s contributions to sustainable urban living through smaller housing units, in effect calling for “tiny houses” or ADUs. By dividing land parcels, housing is slightly more affordable and buying becomes more feasible.

In the 1970s Banham similarly saw the dingbat as Los Angeles’s solution to population density and the ever-present desire for “the illusions of homestead living.” But given Los Angeles’s history of architectural turnover, the winning architects’ call to destroy many of the dingbats before we “get soft and start to miss them” seems shortsighted. With Some Los Angeles Apartments, Ed Ruscha preserved a moment in time when Los Angeles’s last housing shortage seemed resolved. If we are, in fact, experiencing another housing crisis, what will the essence of dingbat-ness look like from the windows of our all-electric vehicles?