Philip K. Dick and the Psychotic Style in American Politics

ONE DAY IN JULY 1974, shortly after the Supreme Court ruling that released the Nixon tapes, Philip K. Dick was craving Chinese. The legendary sci-fi author went to his local spot in Yorba Linda, less than a mile from Richard Nixon’s childhood home. At the end of his meal, he cracked open a fortune cookie. Its message read:

Deeds Done In Secret Have A Way of Becoming Found Out

Dick—who hated Nixon—saw the fortune as more than mere coincidence. In fact, the author didn’t believe in coincidence anymore. Five months earlier, a startling vision had changed his life. The world he occupied was no longer one of historical happenstance, but a simulation imposed by a divine conspiracy.

So, Dick mailed his fortune to the White House. In his letter, he noted the restaurant’s proximity to Nixon’s birthplace, and wrote: “I think a mistake has been made; by accident I got Mr. Nixon’s fortune. Does he have mine?”

The White House never responded. Nixon would resign two weeks later.

Like most Californians of his generation, Philip Kindred Dick wasn’t born in the state. He and his twin sister Jane were born in Chicago on December 16, 1928. Six weeks later, Jane died—a loss that Dick considered formative. At age five, his parents split, taking him across the country. Perhaps to avoid the familial drama, he found solace in the pulp magazines of the youth. Publications like Amazing Stories and Wonder Tales—with their starship captains and shape-shifting reptilians—made his struggles feel remote. He and his mother finally settled in Berkeley in the 1940s.

Sickly and reclusive, Dick was the resident ghost of Berkeley High School. Despite graduating alongside Ursula K. Le Guin (author of sci-fi masterwork The Left Hand of Darkness), neither recall meeting during their time at Berkeley High. Indeed, Le Guin would later claim that “absolutely no one” remembered Dick. His photo wasn’t even in the yearbook.

But Dick eventually found a home in the Bay Area. It provided his first job, his first house, his first marriage (of five), stints in artists’ lofts, and exposure to the burgeoning intellectual scene around UC Berkeley. Shifts at local electronics shops sparked his fascination with technology—especially the new medium of television. Half a semester at the university introduced him to classical philosophy, leading to the central questions of his life:

What is reality? Can we trust the world around us? Can truth be found in what we read in newspapers, hear on the radio, and watch on TV? Or is there something deeper, something arcane, that a grand conspiracy keeps us from realizing?

By 1951, Dick was writing full-time, selling his first story to The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction that year. Combining the outlandish speculations of his childhood pulp magazines with a paranoic outlook, Dick quickly developed his distinctive voice. Post-nuclear wastelands (“Pay for the Printer”), android saboteurs (“Imposter”), and duplicitous aliens (“The Cosmic Poachers”) feature prominently. The same themes would appear in his novels, which he wrote in manic two-week sessions, propelled by handfuls of amphetamines and the anxieties of the nuclear age.

Like Nixon, Dick’s views were shaped by the Cold War. But while Nixon was hunting imaginary communists with the House Un-American Activities Committee, Dick was imagining the futures implied by such planetary paranoia. His ‘50s work pushed a recurring lineup of colonels and company men through the ringer, often trapping them within their own suspicions and greed. Few of his contemporaries managed such razor-sharp satire of the times.

But Dick struggled financially. Although his work impressed genre editors like Anthony Boucher and Donald A. Wollheim, it was seen as pulp, and paid accordingly. While sci-fi luminaries like Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury enjoyed widespread recognition, Dick was relegated to the second tier, his novels condensed onto the flip sides of cheap paperbacks.

That changed in 1962, when Putnam published The Man in the High Castle. His only novel to win a Hugo, the book presents an alternate history where the Axis wins the Second World War. Divided between Japanese and German forces, many Americans adapt to their new fascist overlords. But pockets of resistance remain. A subversive book circulates among the population. Written by a reclusive author in the badlands of Colorado, “The Grasshopper Lies Heavy” depicts a dangerous vision for the occupiers: an alternate history where the Allies won the war.

For Dick, who longed for acceptance in the literary mainstream, the award was bittersweet. He’d written ten realist novels over the previous decade, none of which had sold. After the Hugo, his agent returned the unpublished manuscripts and encouraged him to stick with sci-fi. Dick relinquished his dream of becoming a “respectable” author and doubled down on the weird.

Over the next two years, Dick wrote no less than eleven novels, whose conspiratorial plots make The Man in the High Castle seem tame. Take The Game-Players of Titan (1963), wherein a Chinese weapon sterilizes humanity, and telepathic slugs force the survivors to play a game called Bluff. Or Clans of the Alphane Moon (1964), which finds a divorced CIA agent on an alien moon governed entirely by psychiatric patients. And then there’s the consummately unhinged The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965), in which a drug-peddling cyborg bankrolls the replacement of reality with the communal visions of an alien hallucinogen.

Despite his moderate success, Dick was troubled. Pill-popping, abusive, and evading the IRS, the writer’s incessant suspicions quickly destroyed his third marriage. They would soon upend more than that. On a walk to his Point Reyes writer’s studio, Dick had a vision. The skies around his home ripped open. A metallic face with empty eye sockets appeared, its vacant stare boring into Dick’s soul. Dick considered it an omen. Something he’d suspected for a long time became an unavoidable truth: The world was not what it seemed.

To call Philip K. Dick paranoid would be an understatement. But in the tumultuous 1960s, he was hardly alone. A decade of civil unrest, Cold War standoffs, and Kennedy assassinations proved fertile ground for conspiracies on both the left and the right.

Around the time of Dick’s third divorce, Richard Hofstadter’s seminal essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” appeared in Harper’s Magazine. In it, Hofstadter covered the conspiratorial legacy of the United States, tracing the right’s paranoia—perpetually hunting for communists, subversives, and moral degenerates—back to the anti-Masonic phobias of the 1800s. But in the postwar years, he argued, this rhetoric had swelled beyond the fringes:

Events since 1939 have given the contemporary right-wing paranoid a vast theatre for his imagination … replete with realistic cues and undeniable proofs of the validity of his suspicions.

Like the characters in Dick’s novels, recalcitrant Americans woke up in a country they no longer recognized, and at the mercy of forces they barely understood. Desegregation, welfare protections, and international treaties were framed as apocalyptic harbingers of a “New World Order.” According to Hofstadter, many came to believe that “the whole apparatus of education, religion, the press, and the mass media [was] engaged in a common effort to paralyze the resistance of loyal Americans.”

Such sweeping conspiracies pop up constantly in Dick’s work. But his paranoia went far beyond his fiction. Indeed, “paranoia” scarcely captures the extent of Dick’s neuroses. Yet, although he became increasingly detached from reality throughout the ‘60s, the personal and political crises that led to his repeated breakdowns were undeniably real.

For example: Dick believed he was under FBI surveillance, claiming his stereo system had been bugged in the early ‘50s. In fact, two FBI agents had visited his home then, hoping to identify political activists out of UC Berkeley. While there’s no evidence his Magnavox was tapped, the fact that government agents would canvas Berkeley for potential agitators illustrates the suspicions animating the American psyche at the time.

With a subplot that sees a white nationalist appointed to a government advisory board, The Zap Gun’s depiction of a culture blinded by its own delusions has only become more relevant.

Nowhere is this tension—between specious conspiracies and their basis in historical anxieties—more apparent than in Dick’s critically underappreciated novel The Zap Gun (1967). Written the same year as Hofstadter’s essay, the book epitomizes the absurdities of Cold War paranoia. It follows Lars Powderdry, the preeminent “weapons fashion” designer for West-bloc, an authoritarian hybrid of the UN and NATO. Locked in an arms race with the People’s East (a Sino-Soviet superstate), Lars’ job is to invent new weapons for the West-bloc military.

But unbeknownst to the public, the weapons fashion business is a sham. The real arms race ended years ago, via secretive “protocols” signed in Iceland. Lars’ designs—which he dreams up through drug-induced hyperdimensional trances—are repurposed as consumer goods. As he watches a televised pseudo-demonstration of his newest weapon, Lars ponders its futility. People across the country tune in to see the faked destruction, finding an uneasy comfort in it, leading Lars to conclude that viewers “liked displays of power because they felt powerless themselves.”

With a subplot that sees a white nationalist appointed to a government advisory board, The Zap Gun’s depiction of a culture blinded by its own delusions has only become more relevant. And like a convoluted QAnon message board, it’s conspiracies all the way down: Lars’ hyperdimensional trances turn out to be another sham. His designs are siphoned from the mind of a deranged comic book artist, further blurring the line between fiction and reality.

But Dick didn’t just traffic in fictional conspiracy theories: He lived them too. By the time of Nixon’s inauguration (and another failed marriage), Dick lived in a glorified drug den in Santa Venetia. Friends came and went, Dick holding court over days-long benders.

In 1971, shortly after Nixon ordered a raid on the Brookings Institution, things came to a head: Someone broke into Dick’s home, blew up his safe, and stole his manuscripts. They also took his stereo. The theft—which Dick blamed on everyone from the Black Panthers to the KGB—prompted him to abandon the Bay Area for good. The experience also provided the spark for his excellent A Scanner Darkly (1977).

For a neo-noir about a group of delusional addicts, the novel is paradoxically Dick’s most cohesive. It’s also his best portrayal of the conspiratorial American mind, with deadbeat characters proposing Byzantine explanations for their plights, even as they spy and snitch on one another. Everything from car troubles to an unlocked front door becomes evidence of the conspiracies against them.

But Scanner’s characters aren’t just paranoid—they’re psychotic. They ward off hallucinatory aphid infestations. They fail to recognize themselves in surveillance footage. An undercover narc comes to believe he’s two different people.

This distinction between paranoia and psychosis, often explored in Dick’s work, also presents a contemporary revision to Hofstadter’s thesis. His “paranoid style” has given way to a “psychotic style” in American politics, and its legacy is visible in Philip K. Dick at his most unhinged. As Watergate upended the country, Dick made his final leap into conspiracy: He saw God.

Richard Nixon was the mid-century left’s de facto conspiracy beacon. For Dick and many others, all theories—from JFK to the moon landing—led back to Nixon.

Norman Spinrad, Dick’s friend and fellow author, often discounted his conspiratorial ramblings. But in an interview for Lawrence Sutin’s definitive biography, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick, he recalled how Dick’s views were vindicated by Nixon’s downfall:

Everything Phil thought about the government turned out to be true. Anybody [like him] would be regarded as paranoid and crazy until Watergate broke…

Phil told me another “paranoid” story. He said, “These guys called me up from a Stanford University radio station, came down and asked me all these weird questions. Then when I called Stanford I found out the radio station didn’t exist.” Sounds like more Phil paranoia, except [they did] the same thing to me … two guys showed up and took me to dinner, asked me … all this shit. I’m sure they were agents for some agency.

Watergate led to a reckoning from which American politics never recovered. Faced with a toxic combination of domestic surveillance and the twin Cold War threats of subterfuge and nuclear annihilation, many Americans believed the conspiracists had been proved right. Paranoia gave way to conviction. If the president was a crook, lies and deceptions really were all around.

As it turned out, Nixon was as conspiratorial as the best of them. The White House tapes revealed a man who saw enemies everywhere, including the prime minister of Sweden, Ivy League intellectuals, and, of course, “the Jews.” Indeed, Dick and Nixon are focal points in the multifaceted lens of American conspiracy theories: stare through one long enough, and glimpses of the others appear.

But the administration’s collapse represented more than just a breakdown of public trust for Dick. For him, it was the latest salvo in a cosmic battle between good and evil.

On February 20, 1974, in the depths of national crisis, Dick had a tooth pulled. After administering a “tremendous amount of sodium pentothal” for the procedure, the dentist sent him home. But the numbing wasn’t enough. Dick called a pharmacy, filled his prescription, and awaited delivery. When his painkillers arrived, Dick noticed a fish symbol on the delivery girl’s necklace. She explained that it was the ichthys, a shibboleth used by early Christians. As she displayed it, sunlight glinted off its surface. In an instant, Dick found himself transported back to ancient Rome, in the guise of a persecuted Christian. In fact, a voice told him, he was an ancient Christian. His life was the illusion.

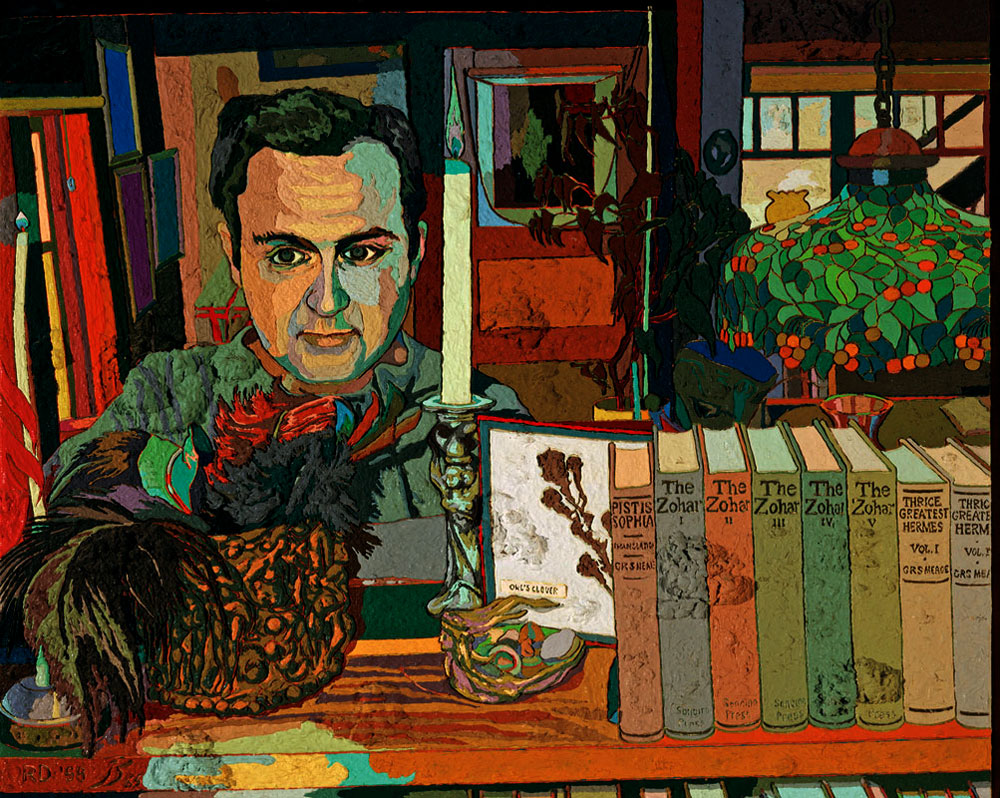

Dick considered it a theophany—direct contact with a divine presence. He would refer to this presence by many names: The AI Voice. Firebright. The Programmer. A “Vast Active Living Intelligence System” (VALIS). Zebra. Over the next month, he encountered it night after night. His unplugged radio spoke to him. Abstract art pieces flashed behind his eyelids. A pink “phosphene afterimage” warned that his son was terminally ill. When Dick took him to the doctor, a hernia was discovered.

These visions—which Dick referred to collectively as “2-3-74,” and fictionalized in his arduous 1981 novel VALIS—vexed the author for the rest of his life. He obsessively documented his experiences, filling over 8000 pages of loose-leaf paper with his hypotheses. Known as his Exegesis, it may be the clearest portrait of a mind on the edge of psychosis ever compiled.

The Exegesis is full of messianic theorizing. And like a mid-century Q with nowhere to post, Dick portrayed himself as the sole prophet of a new era.

In some ways, he was.

Dick’s “schizophrenic turn” has been pathologized by various biographers, explained away as temporal lobe epilepsy or the side effects of long-term drug abuse. Dick himself, a lifelong fan of self-diagnoses, identified with everything from manic-depression to paranoid schizophrenia. But there are cultural factors to consider as well. Indeed, it’s possible to frame his “therapeutic psychosis” as a symptom of the psychotic style developing in American discourse – something brought on as much by his environment as his predispositions.

From Watergate to MKUltra to the Tuskegee Study to PRISM, the US government has repeatedly set aside its principles for bizarre, illiberal, and ruthless schemes. But modern conspiracists warp these facts into harebrained plots that could easily appear in a Philip K. Dick novel.

According to the DSM—the psychopathologist’s bible—schizophrenia is characterized by delusions, hallucinations, incoherent speech, erratic behavior, and emotional dysregulation. Fundamentally, it involves an abnormal interpretation of reality, resulting in bizarre reconstructions of cause and effect, and typified by continual or episodic psychosis.

After 2-3-74, Dick seemed to fit this bill. His perception of reality and the worlds of his imagination converged. He claimed to live through scenes in his books that were, unbeknownst to him, actually scenes from the bible—as if he’d both predicted the future and rewritten the past. His writing sessions lasted through sunrise, even without the amphetamines he’d kicked. In a letter to Le Guin—whom he’d begun corresponding with in the early ‘70s—he maintained that an otherworldly force had beamed sacred knowledge directly to his brain.

Dick laid out the vast cosmology he developed over this period in an infamous 1977 speech. Entitled “If You Find this World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others,” he proposed to an incredulous French audience that Jesus had taught his disciples how to shift between multiversal “matrix worlds,” alleging that we inhabit “a computer-programmed reality, and the only clue we have to it is when some variable is changed, and some alteration in our reality occurs.”

Not only was the world a simulation, but its form was determined by cosmic forces. A godlike “Programmer” eternally faced off against a dark “Counter-programmer,” influencing world events and shifting reality in the process.

While Dick borrowed many of these ideas from Gnostic and Zoroastrian texts, it’s hard not to see the Cold War mentality of dueling superpowers invading his cosmology. Indeed, the premise of two universal forces vying for humanity’s collective conscience would sound familiar to Nixon.

In fact, Dick would invoke Nixon as evidence of this cosmic conspiracy the following year. In “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” Dick insisted that Watergate was proof of these higher powers. The Programmer had intervened, and Nixon was the first in a cabal of politicians and businessmen that would be overthrown. This conviction—that political events have transcendental significance, and that evil-doers will be punished—reflects the long history of American conspiracy theories.

In a modern inversion of Dick’s views, QAnon’s adherents believe that a pedophilic progressive elite is locked in a clandestine battle with the divinely-anointed right. However, like Dick, Q’s followers have gone from paranoid to psychotic. They don’t just promise “the birth and death of whole worlds” à la Hofstadter—they make up new ones as they go along. Constantly updated with the news cycle, everything becomes proof of conspiracy.

At its core, QAnon is a continuation of right-wing conspiracy theories from the Cold War. But its style exemplifies Dick’s legacy—particularly through the influence of David Icke.

Icke—a former BBC sportscaster who built on American arch-conspiracist Milton William Cooper’s work—is the unreferenced source of QAnon’s basic premise. In The Biggest Secret (1999), Icke claimed that a pedophilic global elite ritualistically sacrifices children, draining their blood for its precious adrenochrome. That this elite is controlled by interdimensional “reptoids” from the Draco constellation is usually left unmentioned.

It’s impossible to miss Dick’s influence on Icke’s celestial blathering. Shapeshifting aliens who feed on human suffering and project holographic irrealities from Saturn? That’s the plot of The Game-Players of Titan. Dick, at least, had the wherewithal to consider how these ideas spread. Halfway through “How to Build a Universe,” he addresses the mechanisms of conspiracy: how our viewing, reading, and listening habits produce endless “pseudo-realities,” lulling us into hypnotic, dream-like states. By engaging with mass media: ”We have participated unknowingly in the creation of a spurious reality, and then we have obligingly fed it to ourselves.”

The tragedy is that Dick couldn’t see these processes playing out in himself. His cosmogony is basically a career-spanning elaboration on the finale to his The Cosmic Puppets (1957). As both a chronicler—and a victim—of America’s collective psychoses, Dick fed himself his own reality.

Today, the signs of these collective psychoses are everywhere. Apathy, imagined persecution, and delusions of grandeur are so commonplace as to be unremarkable. Conspiracist talking heads vie for attention with purveyors of the status quo. Bombarded by choice, viewers cling to explanatory nonsense for answers. Like Dick at the end of his life, Western culture is no longer capable of separating social fact from the themes of his fiction.

On February 17, 1982, Philip K. Dick had the first in a series of strokes. He died two weeks later.

In his last months, Dick continued to grapple with his visions. Between instances of associative word salad (another symptom of schizophrenia), the writing in his Exegesis is ecstatic. He truly felt that he had discovered something groundbreaking. As Pamela Jackson and Jonathan Lethem point out in their annotated (and at 944 pages, significantly abridged) The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick, Dick’s fiction—and his struggle with 2-3-74—ultimately dealt with the challenges of revelation. But it’s not just revelation that lies at the heart of Dick’s work. It’s the revelatory power of conspiracy in particular.

Although it’s one of his best-known novels, many people forget the real twist of The Man in the High Castle. In its final pages, a character tracks down the author of “The Grasshopper Lies Heavy” and demands an explanation. What she discovers flips the entire book on its head: In truth, the Allies won the war.

The revelation is far more insidious than the set up. Whether this is metafictional commentary or another conspiracy-within-a-conspiracy is never explained. Reality, again, is not what it seems.

This tendency to find nested conspiracies—so prevalent in Dick’s sci-fi—is what conspiracists thrive on. Like the citizens of The Zap Gun, revelation alleviates the sense of powerlessness individuals feel in contemporary culture. Appeals to “do your own research” are invitations to interact with the psychotic style, offering disquieting solace in place of actual control.

However, despite all the crackpot theorizing, there remain indisputably real things that lend credence to Dick’s (and thereby conspiracy theorists’) obsessions. From Watergate to MKUltra to the Tuskegee Study to PRISM, the US government has repeatedly set aside its principles for bizarre, illiberal, and ruthless schemes. But modern conspiracists warp these facts into harebrained plots that could easily appear in a Philip K. Dick novel.

And for compelling reasons: the recurring tropes of Dick’s stories—celebrity politics, micro-targeted advertising, news as propaganda, omnipresent surveillance, super-intelligent computers, unaccountable corporations, and the banality of life against a backdrop of nuclear war—have renewed relevance in the 21st century. Even though Dick’s villains were those of his day—exploitative capitalists and the American, Russian, and Chinese governments—they still dominate headlines forty years later. The Cold War tensions that haunted Dick and Nixon remain central to geopolitics, in spite of a generation of politicians and pundits declaring them solved.

The psychotic style of Dick’s life and work reflects how discourse has moved beyond truth to relieve that dissonance. But understanding that reality is irreducible to its portrayals, as Dick often reminded us, leads to more questions than answers, opening national narratives to the conspiratorial delusions we see today.

Yet, for all his speculations, Dick harbored his doubts until the very end. He frequently questions his sanity in the Exegesis, never sure of his own theories. It’s easy to imagine a more devious Philip K. Dick as an L. Ron Hubbard figure, duping thousands into a contrived religion. In that way, at least, he separated himself from the worst excesses of the conspiracists.

Dick’s fixations still guide modern life: We still turn to our screens for news and entertainment. We still relish the sordid details of political scandal. America Inc. still competes with a nominally-communist rival for global dominance. And conspiracy theorists still concoct strangely-believable fantasies to explain it all.

So, if you believe we’re on the precipice of a “new” Cold War; if you think truth can be found by watching the right channels; if you believe buying different brands makes you a revolutionary; if you think voting for unqualified demagogues will “drain the swamp”; if you believe billionaire tech founders will really make the world a better place—well, then you don’t know Dick.