In late September last year, a Norwegian surveillance plane dropped a sonar buoy in the Baltic Sea. Its purpose: to send an underwater signal that would trip some C4 explosives laid by American Navy divers, three months earlier, on the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipelines lining the ocean floor between Russia and Germany. It was a good buoy: The pipelines exploded, and President Biden wiped his hands.

This version of events comes from investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, who, earlier this year, published an article on Substack which frames the Nord Stream bombing as a covert and multinational operation headed by the United States. Other reports by media outlets like the New York Times and Der Spiegel have blamed a pro-Ukrainian group of rebels, but Hersh, citing a source with secret intelligence, is sure this was an American act of war.

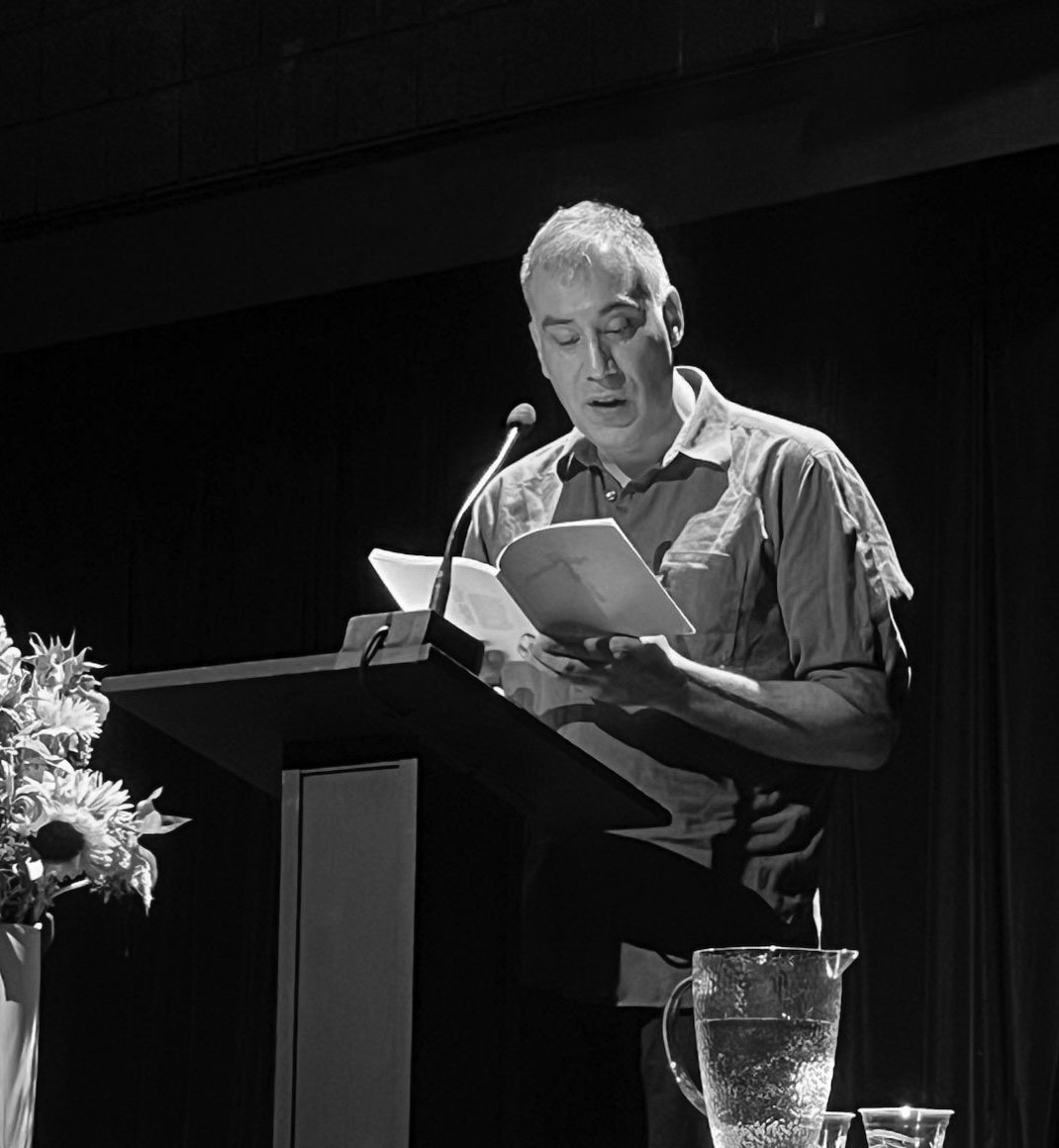

So too was the artist Alfredo Jaar, in February, when he referred to Hersh’s article in a talk titled “It Is Difficult” at Principia College for the Schmidt Family Lecture Series in Contemporary Art. Pacing back and forth on a small stage in a packed Wanamaker Hall, the soft-spoken Jaar, dressed in a black long-sleeved shirt and trousers, called Hersh the “greatest American journalist alive” for holding the United States accountable. In the same breath, he chastised everyone else: “Not a single media outlet in the United States has discussed this discovery, because it’s not convenient—it’s terrorism, an act of war.”

Unmasking the media’s affair with convenience has driven much of Jaar’s work. In 1994, while genocide raged in Rwanda, Newsweek put antioxidants, D-Day, and Jacqueline Kennedy on the cover of its magazine. Jaar would memorialize this “barbaric indifference” in Newsweek (1994), a sequence of seventeen covers from April 1994 when the genocide began, to August 1, 1994, when the magazine finally made Rwanda the cover story. In what came to be the Rwanda Project—25 artworks over 6 years—Jaar asked, How do you represent the unrepresentable truth of human tragedy? “Each project is an answer,” he said. “They all fail and that’s why I keep doing it.”

Jaar is unconventional. In his talk, he introduced himself as an artist who never studied art. “I don’t know what art is,” he said, “but I respond to my context.” Recently, this context, like the context of many who follow the news in the United States, has been molded by images of war in Ukraine. “But the fixation on Ukraine,” Jaar said, “has erased many tragedies.” He referred to a recent cover of the Economist showing a bleeding Ukrainian flag. “I thought, Why didn’t you do a similar cover for all of the conflicts that are identical or worse than Ukraine right now? So I used the cover as a model.”

The day before Jaar’s lecture, a strong wind had blown in from the west, knocking over chairs and grounding branches. On the morning after, when we sat down to talk on the Voney Art Center patio overlooking the Mississippi, the wind had stopped, the river appeared to be still, and it was warm enough to be in a t-shirt and shorts. Our conversation was cut short by the throes of a faculty lunch, but we picked it up a few weeks later on Google Meet. My thanks to Paul Ryan, Professor of Studio Art,for making this conversation possible.

Alfredo Jaar is an artist, architect, and filmmaker who lives and works in New York. His work has been shown extensively around the world. He has participated in the Biennales of Venice (1986, 2007, 2009, 2013), São Paulo (1987, 1989, 2010, 2021) as well as Documenta in Kassel (1987, 2002).

The artist has realized more than seventy five public interventions around the world. Over sixty five monographic publications have been published about his work. He became a Guggenheim Fellow in 1985 and a MacArthur Fellow in 2000. He received the Hiroshima Art Prize in 2018 and the Hasselblad Award in 2020.

His work can be found in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art and Guggenheim Museum, New York; Art Institute of Chicago and Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; MOCA and LACMA, Los Angeles; MASP, Museu de Arte de São Paulo; TATE, London; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Nationalgalerie, Berlin; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Centro Reina Sofia, Madrid; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; MAXXI and MACRO, Rome; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlaebeck; MAK and MUMOK, Vienna; Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art and Tokushima Modern Art Museum, Japan; M+, Hong Kong; MONA, Tasmania; and dozens of institutions and private collections worldwide.

DM: The theme for this issue is “The Postwar,” and the way the editors define it is very conventional–from the end of World War II in 1945 to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. But as you showed us in your talk, there really isn’t a postwar.

AJ: Well, you’re right. In thinking about “postwar” today, in light of what’s happening around us, “postwar” is an illusion. And this so- called postwar really planted the seeds of the next war. And that’s where we find ourselves today.

But maybe the years since 1991 are different.

I went to Rwanda in 1994 to witness the genocide. That was a turning point in my life. I came back from Rwanda ashamed of being human. That tragedy was one more consequence of the colonization of Africa by Europe—in this case, Belgium. Witnessing a genocide, and being in refugee camps with a million people, and being in a church where 565 people were killed—I’m walking around bodies, corpses on the ground—I was not thinking about postwar. The more I say “postwar,” the more absurd it sounds.

Your lecture felt like a postcolonial critique of war. When you showed those photos of Alan Kurdi and quoted Mario Calabresi—“This is the beach where Europe dies”—I was reminded of something Aimé Césaire said: “Europe is indefensible.”

This idea of “postcolonial” is as illusory as “postwar.” Unfortunately, the “colonies” are pretty much alive, not in a clearly physical way, but in a virtual way. In a structural way, they’re still functioning as colonies. The former colonies are extremely dependent on the former colonizers. And conflicts exist now because these former colonies that are still colonies are trying to distance themselves from that system of oppression.

It is well known that the reason for the Iraq War was because Saddam Hussein had decided to sell Iraqi oil in Euros and not in US dollars. That was shortly after the birth of the Euro. At first, the US thought the Euro was a joke, but then, they panicked. They said, We cannot allow this. So they invaded, inventing the war on terror and weapons of mass destruction. September 11 was completely unrelated.

It is very difficult for the former colonies to actually break those structural bonds. The US will not concede the supremacy of the world to Russia or to the Chinese or to a world that is more equal. As I said yesterday, I’m very pessimistic. Intellectually, I don’t see any hope, but my will is still optimistic. It’s interesting how we are really talking about language, how language exists to give us the illusion of stability. It’s better for business.

You were very adamant about naming the real winners of the war in Ukraine—weapons manufacturers like Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman.

Beyond the bias, the Economist has an enormous amount of information. They recently mentioned a statistic that is just mind blowing: Ukraine is using more shells—more guns, tanks, missiles— per month than the United States has the capacity to produce in one year.

Alfredo Jaar, Mea Culpa, 2022. Courtesy the artist

That’s unfathomable.

And the numbers, I don’t want to repeat the numbers because I don’t remember them. We’re talking 15,000 thousand of these, 35,000 of that, 17,000 of these. So what Ukraine is using per month is more than what the entire defense industry in this country—which is the largest in the world—is producing in one year. Imagine what it means in terms of business for these companies.

Do you think of yourself as a dissident? The way you appropriate and recontextualize images strikes me as a kind of dissident activity.

I’m an artist, and in some of my works I’m also an activist. I prefer the word activist. But most of all, I try to make sense. I’m a humanist that tries to make sense. And, as someone who is interested in semiotics and the politics of images, I hate to be manipulated. When I feel manipulated by a magazine or newspaper or TV program and so on, I feel the urge to respond even though those responses are silent echoes that no one hears. The lecture is an opportunity for me to actually share them with a limited audience.

But it never reaches the ideal receiver, the person I’m trying to reach and say, “Hey, this is not correct. This is the way it is.” But I don’t know. I have no idea if, when they get this stuff from me, if they have difficulty sleeping at night—that would be a dream.

I’ll have to ask my students if they got any sleep last night.

Were you aware of these two islands, Nauru and Manus?

Oh yeah.

Are they in the news in Australia?

Recently, the news is about Labor’s attempts to resettle the asylum seekers that the previous government sent to Nauru and Manus because they refused to process them in Australia. What isn’t in the news is the fact that this Labor Government, under Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, is continuing the previous conservative government’s agenda—Operation Sovereign Borders—where people seeking asylum on boats are turned back before they can get to Australia. It’s insane.

And, you know, besides being insane, it is illegal. What the US is doing, what Australia is doing, what Europe is doing—it goes against the Geneva Convention. No one talks about that. But when a big country like the US is doing it, other countries realize they have permission to do it, and they know no one will touch them.

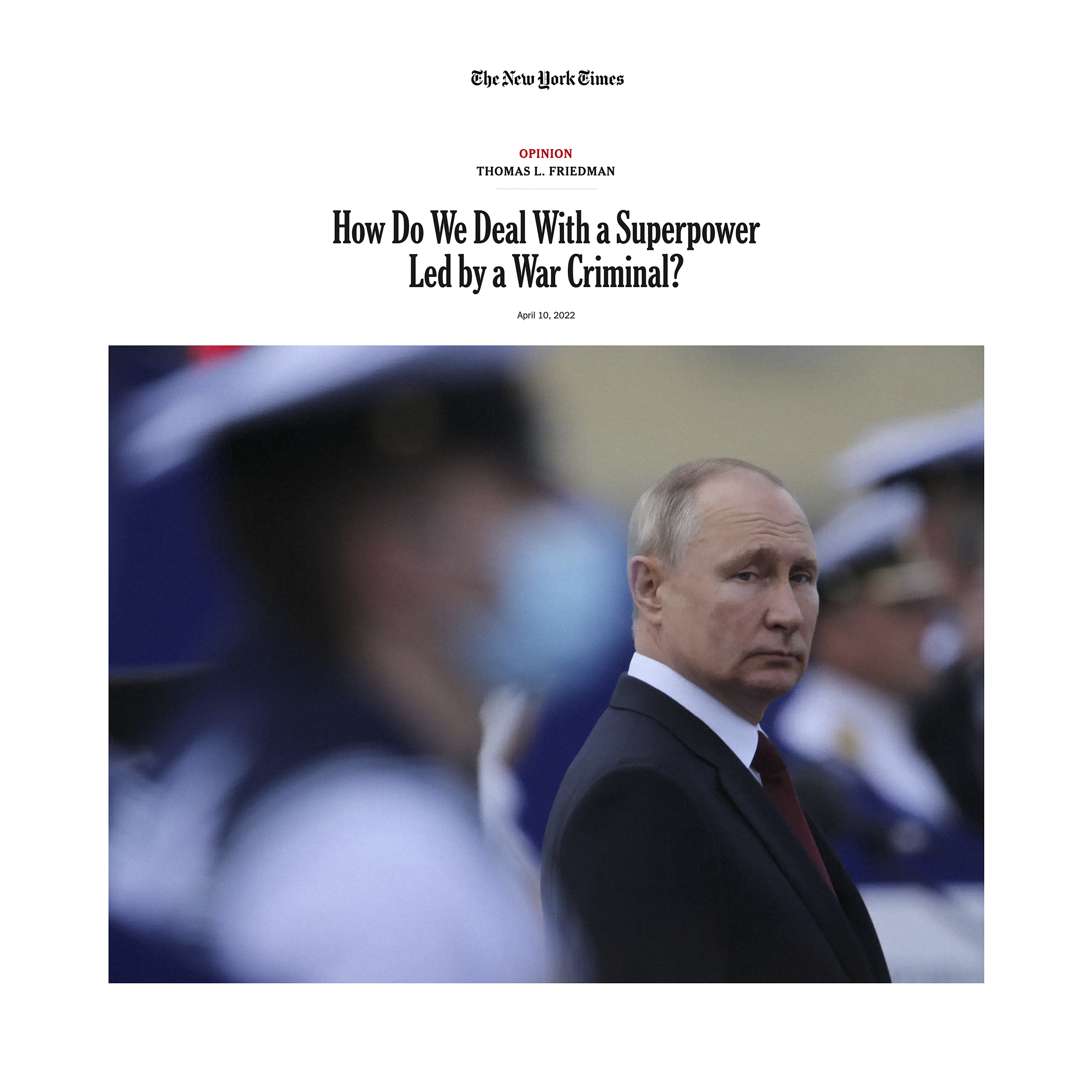

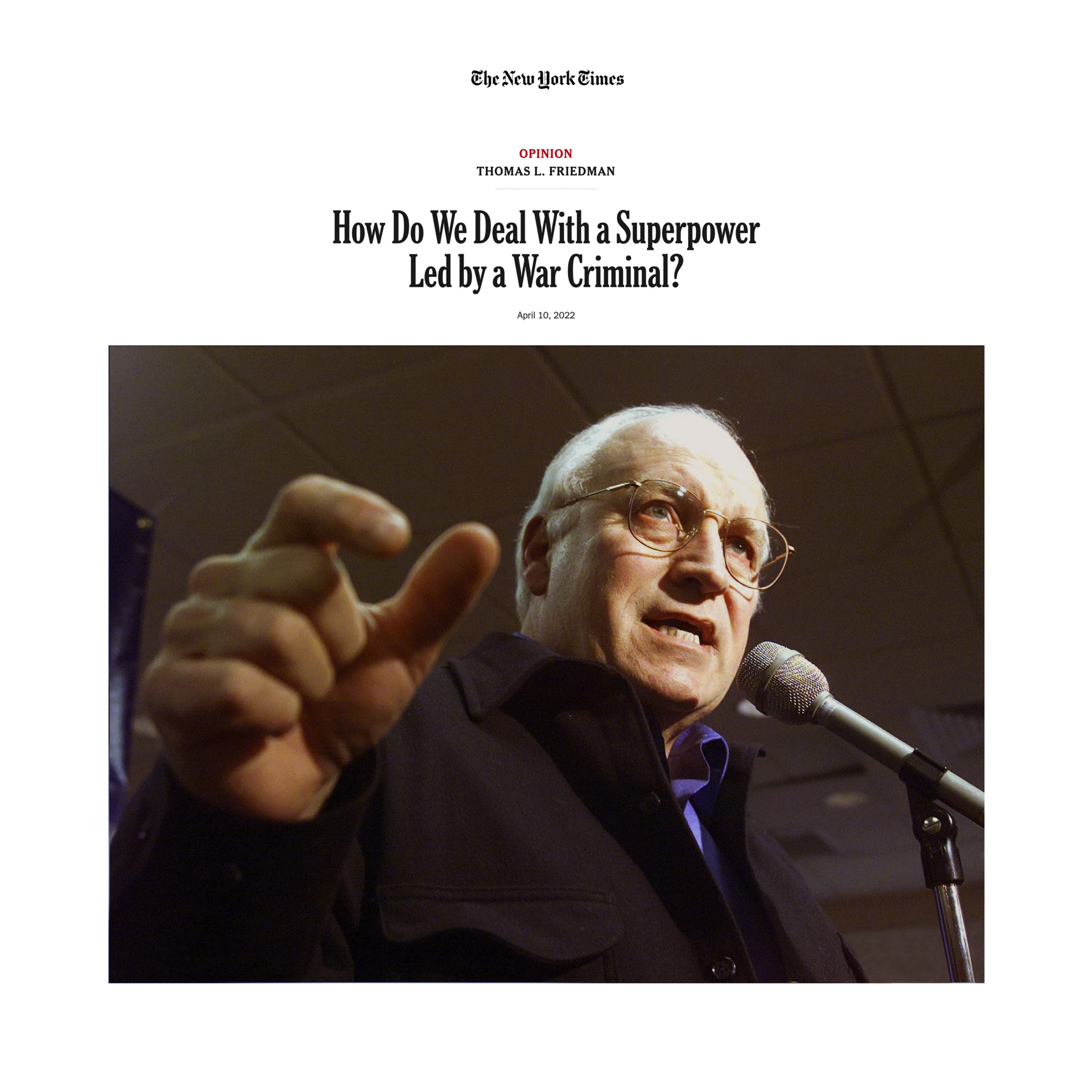

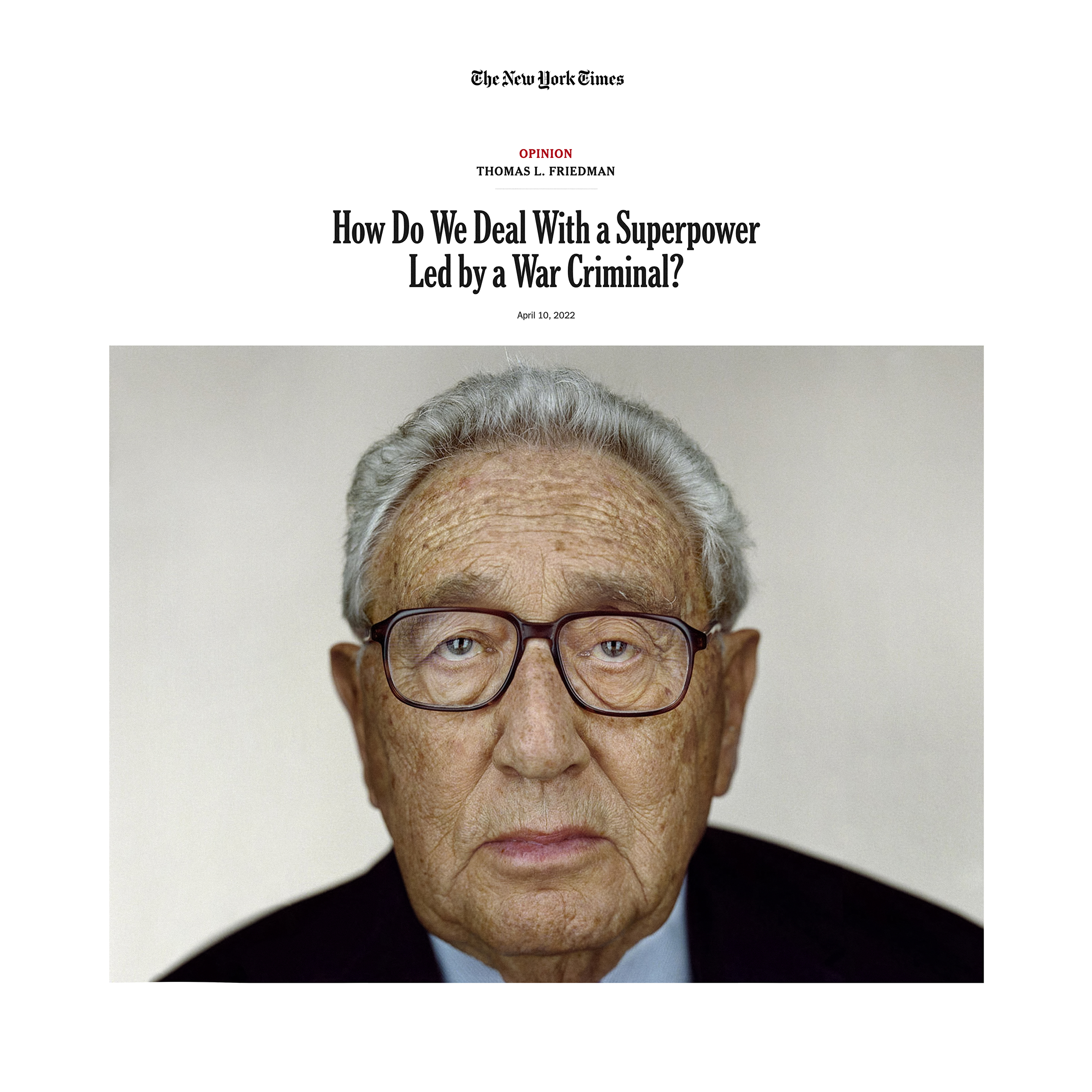

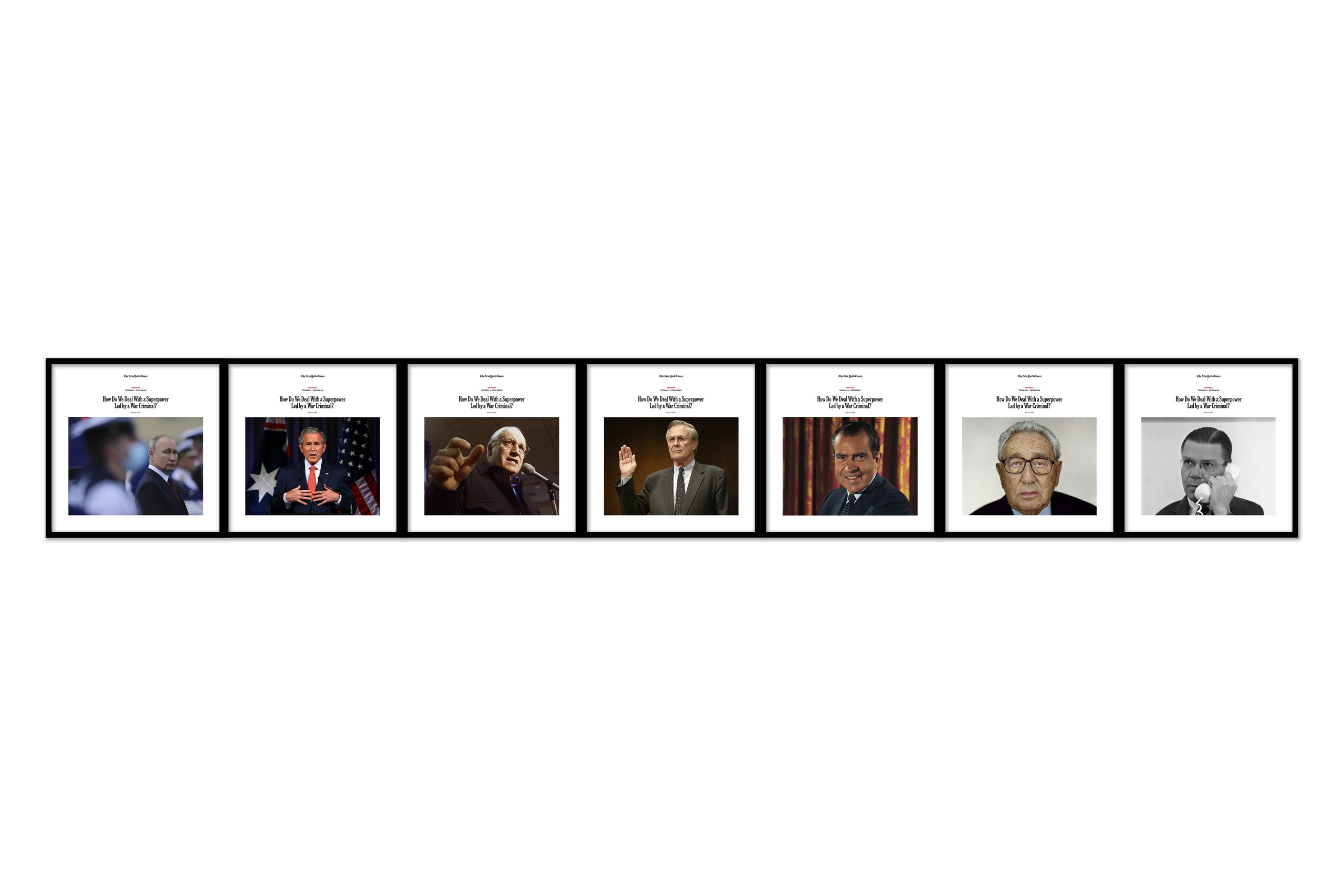

Alfredo Jaar, War Criminal, 2022. Courtesy the artist

The title of your lecture is “It is difficult.” Will you talk about that wording?

This is a title that I’ve used for the last fifteen years. I would give a lot of lectures and I was tired of coming up with a new title every time. I start my lectures by saying that I’ve been an artist for four decades, and it is not becoming easier. It is becoming more difficult to be an artist. So it’s about the difficulty of being an artist today, about how we make art when the world is in such a state. How do we make art with information that most of us would rather ignore? The words come from a beautiful poem by William Carlos Williams, which I also quote often in my lectures:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

It’s an extraordinary poem.

That “there” could be in the poems or in the news.

Exactly. That’s where it is.

How would you describe the state of the news and media landscape today, and how has this landscape changed—or remained the same—since you began paying attention to the news?

The internet has created a small revolution of sorts because now the news is a public space open to almost everyone. Social media has become a place where news circulates that wouldn’t necessarily make the front page of the papers or magazines or even TV. It is an extraordinary counterbalance to the extraordinary bias of our media system. This bias has always existed, but in situations like the Ukraine invasion, it has never been more clear that Europe and the United States have one vision of the world, while everyone else has another vision. Europe and the United States represent only 14% of the world population, and only 14% of the world population has approved of the West giving arms to Ukraine. But Western media makes us feel that this is world opinion. It is not.

I would say that the world wants peace and negotiation. The US has been stopping negotiations because they want Putin to fall. They don’t care if more Russians and Ukrainians die. The US is feeding this tragedy. The Chinese are proposing a ceasefire and the US is saying, No, it’s too early. They want to set up the parameters of this war and the parameters of this possible ceasefire. But you’ll find counterbalanced information and opinions on social media. Of course, it doesn’t have a presence in the world like most of the media, but more people are reading these things and starting to think differently from what they are being told to think.

You use the methodology of an architect to make art. “For an architect,” you said in your lecture, “context is everything. An architect responds to his context.” Your recent press work responds to Western media representations of the war in Ukraine, but you call these responses “therapy.”

I’m perfectly aware that the effect that I may have doing this work is minimal. So if I’m asked, Why the hell do you do it, I say that it serves me as a kind of therapy. It’s a way for me to express my rage, to express my outrage, to express my opinion, and to share a more balanced view of the situation with the audience. I know it’s a lost cause, but at least I’ve done something about it. Going back to Gramsci, it’s my will acting like this because it offers a breathing space. But intellectually, I know that it’s not going to make a big difference. But for every person that sees and agrees with me, I get some joy.

I’m showing these works in London next month. I don’t know what the audience will be. I don’t know what the press will be like, but I’m hoping that it will have some kind of impact, even though the situation is tricky: I’m criticizing the press and I’m hoping the press will talk about the work criticizing the press. So it might not happen at all. Even though I’ve always believed that no institution is monolithic. When we look at something like, for example, the New York Times, of course, they have an extraordinary bias. But within the New York Times, there are individuals, and once in a while, some of these individuals manage to stay afloat of the ideological agenda of the New York Times and say things that manage to go through the editor, the censorship within the paper.

So if I’m asked, Why the hell do you do it, I say that it serves me as a kind of therapy. It’s a way for me to express my rage, to express my outrage, to express my opinion, and to share a more balanced view of the situation with the audience. I know it’s a lost cause, but at least I’ve done something about it.

Returning to the way poetry enters your work, I wanted to ask you about Pier Paolo Pasolini. He’s an important postwar figure, and you’ve described him as an influence.

Pasolini is one of my heroes. He was not only a writer, a poet, a filmmaker, he was an intellectual. He was a critic and polemicist. He was someone involved in the culture of Italy and Europe. His voice was the voice of the intellectual, and he was someone that would take risks intellectually all the time. A famous case was in Rome in 1968 after the battle of Valle Giulia, a huge confrontation between the police and Communist students. The students were protesting, but Pasolini wrote a poem where he sided with the police. Of course, the entire Italian left took the side of the students. But Pasolini said, No, in this case, I’m with the poor who have been forced to police you because they have no other choice. No intellectual today would take a risk like that. Now, this was a very specific case. But Pasolini has always been the model of intellectual I want to be.

How do you model yourself after Pasolini?

He was always speaking out and giving his opinion, not only within the world of culture, but also in the world at large. That’s what I try to do. Sadly, the art world is a world of fiction, and it’s very self-referential. You walk around Chelsea, where my studio is now, and you go from gallery to gallery and you don’t see anything about what’s happening around the world. Very few artists touch on subjects other than themselves. I’m interested in the world in which we live, and I’m interested in responding to what’s happening around me. I’m trying to get out of this world of fiction. I’m trying to get reality into the world of art. Another way of thinking about Pasolini is that he was making connections. A protest was not just a protest. A cultural event was not just a cultural event. He would write about these events and connect history with the present and what it means for the future. That’s a skill that very few intellectuals have. Finally, he was a risk-taking intellectual. Perhaps Chomsky is the closest thing today. Chomsky can say whatever he wants and remain untouchable.

Pasolini said that culture is a prison for the intellectual. This was the basis of your installation, Infinite Cell, in The Gramsci Trilogy from 2005. Is risk-taking the way out of this “culture prison”?

He was suggesting that the world of culture was a prison because we were in it and not looking at the world at large. He wanted to get out of that “prison.” The only way to do that is to get out of the gallery, the museum, the theater. I created Infinite Cell in homage to Pasolini. It’s a normal cell inside a gallery, but there are two walls that are mirrored. So when you are inside, you look left, you look right, and it’s completely infinite. The cell never ends. I was trying to represent that infinite cell he is talking about by inviting people to enter and see how it feels to be in that infinite cell—which is, for me, the world of culture—and then to get out of that cell. He was criticizing the world of culture, not because of culture itself. Culture is a marvelous thing that exists for me, culture is a way to breathe. Nietzsche said that in a world without music, life would be a mistake. To paraphrase, a world without art and culture would be a mistake. It would be unlivable. Pasolini believed in culture, and that’s why he was such a prolific producer of books and poetry and films. He didn’t reject culture, but he wanted to make culture with the world, not the self.

And he was critical of postwar Italian consumerism, especially television. He loathed the “dogma of religion.” He was “unique,” Gary Indiana wrote, “in his nervous mingling of intense, alienated Catholicism with Gramscian Communism.”

Of course, that was part of his critique. Culture was not only a cell, but it was a cell participating in the market forces of neoliberal capitalism. He was fighting from all sides. He was desperate.

Desperate, passionate, controversial. He strikes me as an iconoclast, which is how I think of you—the way you refuse to take images in the media as truth.

I did a film on Pasolini called The Ashes of Pasolini. I made it in Italy for the Venice Biennial at the time of Berlusconi. He had four terms as president. He was Trump before Trump. He owned most of the media in Italy. He had a dictatorship of the media through his company, Media Set. At that time, I thought that Italy needed a voice like Pasolini to express his dissidence.

I was hoping you could talk about your recent show, “The Temptation to Exist.” It includes works by artists from 1950 to the present, so it strikes me as a melting pot of postwar consciousness—from the point of view of the artist.

I had never done a show like this. It was almost like a public confession—as an artist intellectual— of how I felt at that time. Normally, I leave the biographical stuff outside of my work. I’m very shy and reserved and introverted. But Galerie Lelong had invited me to do something. At that moment, I was having a big piece at the Whitney Biennial, but I accepted the challenge.

So I left the main space of the gallery empty— this is 90% of the gallery—and illuminated it with red lights. I created a very dense red light in the entire space. And when you reach the end of the space, you find a huge neon, which had a quote from Seneca:

WHAT NEED

IS THERE

TO WEEP

OVER PARTS

OF LIFE?

THE WHOLE

OF IT CALLS

FOR TEARS.

That Seneca quote set the stage. The neon was red and it was big. To add to the red atmosphere we installed red lights on the skylight, on the windows at the entrance, and on the ceiling. I wanted to suggest a space of loss, a space of mourning, a space of melancholy, a space of nostalgia, a space where I declared, “I’ve been an artist for 40 years, and I have no idea what to do today.” This was at the start of the supposed post-Covid era. The war had started in Ukraine. Roe v. Wade had been defeated in the Supreme Court. And so on. I was at a loss, and I didn’t know how to move forward. The red space represented that reality.

But the gallery also has a small space, which is completely separate from the big space. And I thought, Alfredo, don’t be so hopeless. Offer a counterbalance. Explain why you are an artist. Why, like Gramsci, you believe that art can effect change. So I had this idea, and I drove the gallery crazy because it was all loans. They brought them from Europe, from Asia, from Africa. It cost them a fortune. Nothing was for sale. But they believed in the idea. So we had this extraordinary exhibition. There were more than a hundred works in that tiny space, because I wanted to create an explosion of meaning, an explosion of resistance, an explosion of joy. I wanted to say, “This is how I feel within the red space—I’m lost. But go into the next room and see what art has been able to do.”

I was very biased. I chose works that I like. I have no idea if other people like them, but these are works that have been very important in my life.If I had to make a list of the 10 top works in the history of art, most of them were in that space. I think they’re absolutely brilliant in the way they think about an issue and then resolve the issue and communicate this to the audience. The gallery almost went broke. Nothing sold, absolutely nothing, because the works were owned by the artists or by collections. But galleries have their programs. They have their best sellers. And they have artists like me that they think are important to show, to complement their program, and who do not follow the market system.

I noticed there were only six portraits of Pasolini.

The gallery said, “Okay, Alfredo, bring one.” But I brought six. And I requested the photos by Letizia Battaglia, who sadly passed away a week after signing those six prints—and that’s why I dedicate the show to her at the entrance. So I wanted the pictures of Pasolini to be a kind of mantra everywhere. Pasolini, Pasolini, Pasolini, Pasolini. And Gramsci. I have made a lot of Gramsci drawings. There was a time where every morning I would do one Gramsci drawing. So I selected a few, and they’re also in the show. Pasolini and Gramsci everywhere in between the other works. That was the idea.

You mentioned your “top ten” in the history of art. Which ones fall under this category?

Well, take the piece by Lawrence Weiner. This is a 1x1m cut in the wall—above the Valie Export—where he suggests that you have to make a 1×1 meter cut and remove the first layer of the wall to reveal what’s behind. That’s the work. It’s from 1968, and it’s owned by MoMA. You have to ask for a permit, a loan, even though MoMA doesn’t give you anything. You have to do everything yourself. And it takes a year to get that permit because the MoMA is a huge bureaucratic machine. But we managed to get it. That’s one of my favorite works of all time. I mean, context is everything, and that work simply tells you, Let’s look behind this wall. I love those kinds of gestures. As I said, most people don’t give a damn about that hole in the gallery. People asked, What is that hole doing in the middle of the gallery?

That work is similar to the Hans Haacke piece, which is called Condensation Cube (1963-64). This is also one of my favorites of all time. It’s an extraordinary work. This is when he was working with natural systems before moving into political systems in the Sixties. Basically, it’s a cube filled in with a couple of inches of water, and it responds to the temperature of the room—if it’s cold or hot or windy or if there are people inside, all of these things change the temperature and create condensation within the cube. So the cube is a perfect thermometer that is reading the context of the gallery space. Those things drive me crazy. I love them.

Another one is Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1965) that she did very young in a theater in Tokyo. It was a performance, one of her first performances. And she kneels on the stage in a dress, and she invites the audience to come up with scissors and to cut a piece of her clothing. So they come and cut and cut and cut. And in the end, she’s almost naked. She has to protect her breasts because whatever is left is starting to fall. I think it’s one of the most beautiful, poetic and intelligent pieces of all time. Another work in the show is Mirror Piece (1969) by Joan Jonas. This is also in the Sixties, when she did a performance with a group of young women. They all went out with mirrors, and the mirrors were reflecting everything around them. They sat on the grass with the mirrors hiding their bodies, but showing the sky, and so on. It’s a beautiful and poetic piece. It’s also about context, about saying, Look at the world! Look at the world! So that’s what these works do. They think about the world and not only about the so-called art world. And that takes me to James Baldwin’s quote, when he says, “Life is more important than art. That’s why art is so important.”

And that’s what we do as artists. We insert ideas into existing ideological circuits.

There’s a photo by Shirin Neshat, from her Women of Allah series, to the left of Weiner’s 1x1m hole in the wall.

Above the big Pasolini.

Yes, above the big Pasolini. In this photo there is a Muslim woman and she’s pointing a gun at the viewer. Across the room, there’s a photo by Juan Downey, Yanomami with Camera. In both of these images, the subject points a machine at the viewer—a gun, a camera—in such a way that they could be the same thing: gun as camera, camera as gun. Do you see it that way?

I didn’t think about that connection. A lot of artists who are activists, like me, think that if we were not artists, we would be freedom fighters. We would be so-called terrorists. We would do things out in the real world. So art is a place for us to express ideas and critiques, but in peace, and in the space of culture. I always like those works by Shirin because they show women taking arms and reacting to what’s happening around them. She’s from Iran, and she was speaking specifically about the context of women in Iran. She’s a good friend of mine.

Juan Downey’s image is one of three images that do something I have never seen before, and I had always wanted to put them together. One is the image by Claudia Andujar, a Brazilian photographer that went to the Amazon, even before Juan Downey photographed the Yanomami on the Brazilian side. Juan Downey visited the Yanomami in the early ‘70s on the Venezuelan side. These are the two artists that are very well known who have worked with the Yanomami. Today we are interested in Indigenous rights and so on. But this was in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. So I thought it would be interesting to have Claudia’s image, which photographs the Yanomami, next to Downey’s image, which shows the Yanomami photographing him.

Those were two very important images that I wanted to connect. And the third image is the one above them by Giuseppe Penone, which is a work that I’ve always liked—it’s in my top 10. In that piece, Penone put some contact lenses that are mirrored in his eyes. So he’s reversing his eyes. He’s not seeing anything. And when you look at him, you see yourself in his eyes. Because it’s a mirror. So the piece is called, To Reverse Your Eyes. It’s not about looking in, but looking out. It’s a fantastic piece from the early ‘70s. They never picked him as part of the so-called arte povera movement. But for me, that work is one of the most important of that era.

Before we end, could you talk about your work in the show? I’m thinking of your early work, which you made in response to the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile—like 11.9.73.1210.

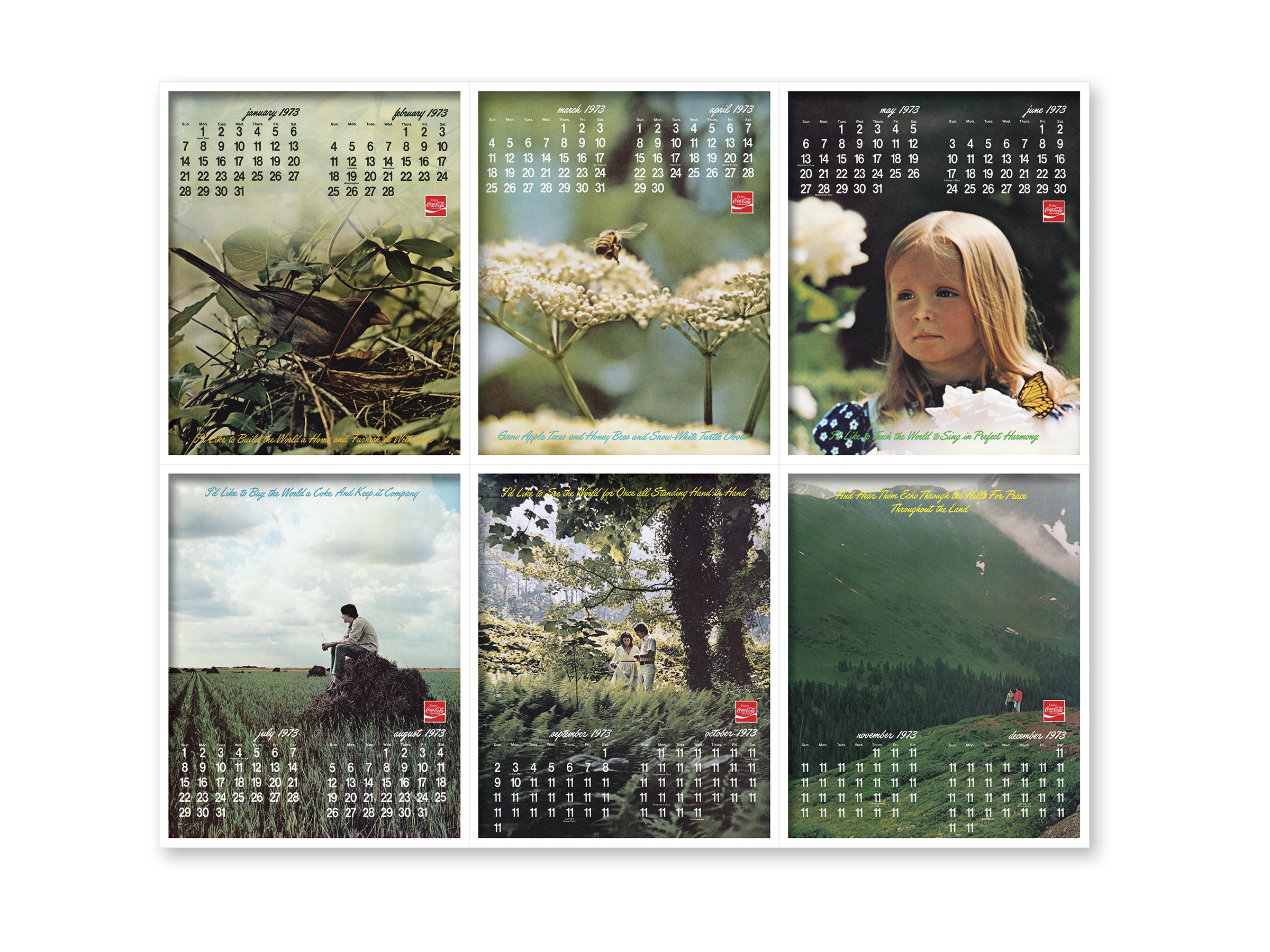

There are a few works about Chile. There’s Studies on Happiness. And my small Coca-Cola calendar, which I put next to the Coca-Cola bottles by Cildo Meireles, a piece that he made in response to the military dictatorship in Brazil. I thought it would be interesting to add Cildo’s bottles to help explain my own context and how I learned to react to my context, which was a different world—censorship, killings, and so on. So my Coke calendar is a kind of homage to Cildo’s Coke bottles. This is when I was born, let’s say, metaphorically, intellectually, as an artist.

In the Seventies, Cildo was living under the dictatorship in Brazil. He was a young artist just starting, and he would go to a bar and he would drink a bottle of Coca-Cola. At the time, the bottles would be sent back to the factory. They were washed, filled again with Coke, and sent back to the bar. There was a continuous recycling of the glass bottles. So what he did was design an adhesive with white text that had messages against the dictatorship and against the US, who had, of course, supported the coup. He would say, YANKEES GO HOME!, or messages like that.

So he would go to the bar with friends or alone, he would drink a Coke, and maybe if no one was watching, he would take the bottle to the bathroom and glue this calcomanía, this adhesive, on the bottle. But because the letters are white and the bottle is empty, it’s transparent. You don’t see anything. But when these bottles get refilled, the text becomes readable. They reveal themself only when the Coke is back inside the bottle. In the factory, no one was checking the bottles. So they would just fill them up and send them to the bars. And in the bars, someone is having a Coke, and suddenly they find this message, this subversive message against the dictatorship coming from the Coke factory. That piece is called Insertions into Ideological Circuits.

11.09.73.12.10, 1974. Courtesy the artist

September 11, 1973 (Coke), 1982. Courtesy the artist

And that’s what we do as artists. We insert ideas into existing ideological circuits. That’s why it’s one of my favorite pieces. I have it in my home. I have three bottles in my home and I live with them. When I created the Coke calendar, it was an homage to Cildo. I was using a formula I had been using in the ‘70s in Chile, where I was suggesting that after September 11th, 1973, every day is an 11th. The nightmare had started and we didn’t know when it was going to end. It took 17 years.

But you mentioned this piece, 11.9.73.1210, which I made when I was starting my studies of architecture. I had discovered Letraset, those plastic letters used to mark floor plans and drawings. They sell sheets of these letters in different sizes. And you glue them with a little instrument on your floor plans. I discovered these letters and I was in love with them. I was playing with them. So a year after the coup, I had this black cardboard on my desk, and I thought, I’m going to play with Letraset. And I thought, I’m going to put the date of the coup, which marked my life, which changed my life. So I put 11 September 1973. And when I finished, I felt that first it wasn’t dense enough, it was too simplistic. It was good for me because it was a reminder of what changed my life, but I wanted something more. Instead of cutting the board, I thought it would be nice to add something to make it symmetrical. I thought, I’m going to put the time of the first bomb that destroyed the Moneda Palace, which was the presidential palace. And that was at 12:10. So then it became 11 September 73, 12:10, which is an even more precise moment when the catastrophe started, when the first bomb fell on La Moneda.

For some reason I kept this piece, because I keep everything. And then much later, 20, 30 years later, I thought, it looks like this was my first artwork, the first time I did something that went beyond graphic design. And now it’s part of my works from that era. It’s a very biographical work. And it’s a gesture to incorporate my biography and to, again, confess: This is when I was born, this is what I like. This is how I think, this is who I am. And I’m at a loss right now in the red space.

I have never been so naked in an exhibition.