Nature

noun

The phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth, as opposed to humans or human creations.

Wilderness

noun

An uncultivated, uninhabited, and inhospitable region.

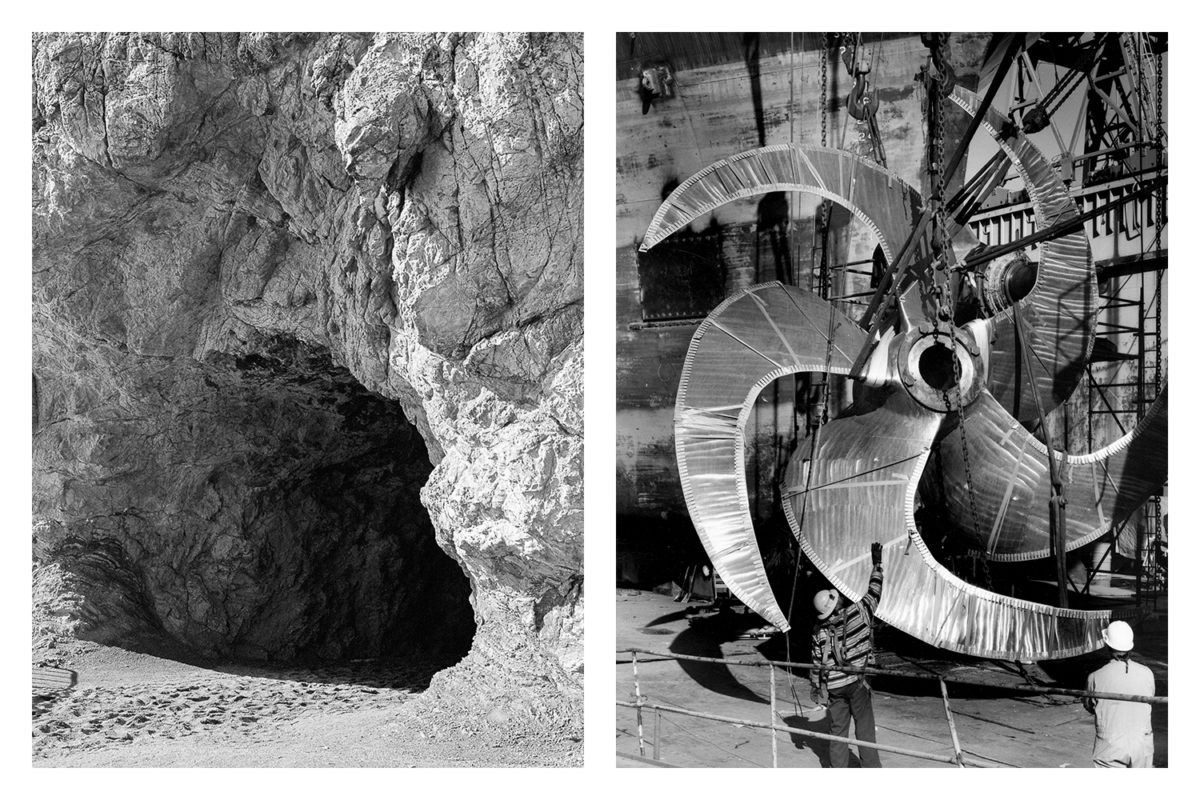

SEEMINGLY BENIGN, “nature” and “wilderness” frame a worldview we are often scarcely aware of. The words form an anthropocentric dichotomy between the human and the other-than-human, limiting and forming the world more than they describe it. To speak of “nature” or “wilderness” in California is to erase its First People. Yet, what is a city without wilderness? To Native Californians, the land is alive and inexorably tied to them as they are to it. Since Time Immemorial, Native Californian have tended to the land. Over time they formed a relational landscape of remarkable abundance scarcely equaled on the Earth. Colonizers mistook this relational landscape as “natural,” and the ramifications of this mistake grow annually.

The City was not born from chance. Located at the convergence of seemingly innumerable biotic, geographic, geologic, and hydrographic networks—the City exists because of its heightened and localized potential to extract [verb. remove or take out, especially by effort or force] and consume [verb. use up (a resource)] the networks of the land. Indeed, the growth of the City depended on its consumption of Native lands and Native bodies—a period of time in California when it was bluntly referred to as extermination. The concepts of “wilderness” and “nature” engendered this genocide, transforming populated cultural landscapes into unpossessed lands, and ripe for extraction and consumption. “Wilderness” enabled the Gold Rush; it gave a moral rationale to clear cutting the redwoods and hunting the California Grizzly to the point of extinction. Through this lens, it can be said the City exists because of “wilderness.”

In contrast, the Ohlone, Coast & Bay Miwok, Patwin, and Delta Yokuts have lived in reciprocity with the landscape since they came into being. To stand among the redwoods on Mount Tamalpais or the manzanitas of San Bruno is to be present within Native California culture and agency. Admittedly, Bay Area ecosystems are fractured and isolated—we can also see them as ardently defiant of the City and its sprawl. Coho and chinook salmon still migrate up the Sacramento River toward concrete tombstones, rebelliously spawning in the shadow of obliteration. The long-thought-to-be lost Presidio Manzanita awoke along the El Camino Real after more than a century of slumber—who knows what else is still sleeping? Wolves are remembering our woods, and one by one returning to reclaim what is theirs. It is no longer a question of if the Condor will return, but when.

To ponder the fate of the City, I look to its birth—its purpose for being. Though its economy now hinges upon extracting the details of our lives rather than the essence of the land, an extractive ethos remains—and with it, assured collapse. This should come as no surprise in a landscape of sinking skyscrapers, rising seas, dying forests, tainted waters, depleted fisheries, apocalyptic fire-cycles, and lingering drought—all precariously balanced upon tectonic plates locked in a tango where one eventual move will obliterate every aspect of security and safety.

To see the City we must see it weighted by “wilderness;” through reevaluating “nature” we interrogate our tacit assumptions of personhood and self. We must ask ourselves: Whose lands are we on? Whose abundance are we extracting? Whom are we harming for our convenience? These questions cannot be answered in isolation. But in the Bay Area, it’s a process that can begin with #LandBack and #SaveTheBerkeleyShellmound, led by Native Californian voices. The City’s boundaries are imaginary, an arbitrary circumscription in a vast living network stretching across the hills, creeks, rivers, valleys, mountains, through the earth and sea. The abundance of these networks served as the impetus for the City—I see no reason why they won’t direct its fate.

Devlin Gandy