Exile and the Kingdom

IN AD 330 CONSTANTINOPLE, rising at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, was inaugurated as the New Rome. In 615 Jerusalem was lost to the army of Chosroes II, the Great King of Sassanid Persia. After slaughtering almost all of the Christians and burning down the church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Persians carried away the True Cross as a trophy for their shah. Within a decade, the Persians and their “barbarian” allies, the Avars, were besieging the City itself. It was the climax of what J. M. Roberts calls “the last world war of antiquity,” resuming as it did a thousand-year-old clash of civilizations.

Led by the soldier-emperor Heraclius, the Byzantines thrust back the invaders on land and sea, sending the Great King into a flight that ended at his capital Ctesiphon. Deserted by his disillusioned troops, Chosroes was deposed by his son Kavahd, who had him shot slowly to death with arrows. In the peace talks that followed, Heraclius recovered the True Cross, which was transported to Byzantium and stood upright on the high altar of Santa Sophia in a triumphant mass. After this miraculous history, the New Romans had every reason to believe that Constantinople had become even more a heavenly city, in fact, a type of New Jerusalem, inevitably eclipsing the significance, for them, of the original. In any case it was lost, in 635, to the caliph Omar, whose conquests reversed all that Byzantium had regained in the Middle East and enlarged an Islamic dominion which eventually extended in the West to Iberia.

For the next five and a half centuries, while it remained under Muslim authority, the Latin West continued, albeit in a detached way, to regard old Jerusalem—King David’s city—as the center of the world, where in due course the Messiah would reappear, this time, ideally, in gilded armor and riding a white charger. Meanwhile, Omar had decreed a policy of toleration toward his Jewish and Christian subjects, which, continued over the centuries by his successors, was more than their sects accorded one another.

In the 8th and early 9th centuries the emperor Charlemagne and the Abbasid caliph Haroun al-Raschid (of Arabian Nights fame) maintained a cordial long-distance friendship founded, says Gibbon, on “a similar supremacy of genius and power.” It was kept up by the regular exchange of gifts and embassies. Al-Raschid possessing the larger and more opulent domain, his gifts were grander, including a water clock, an elephant, and the keys to the Holy Sepulcher. The Frankish protectorate in Jerusalem implied by Raschid’s bequest led to benefactions by Charlemagne (a hospital, a library) and cultural exchanges between the Christian establishment in Jerusalem and the West, eventually giving rise to the legend that Charlemagne had actually reigned in Palestine as the first crusader.

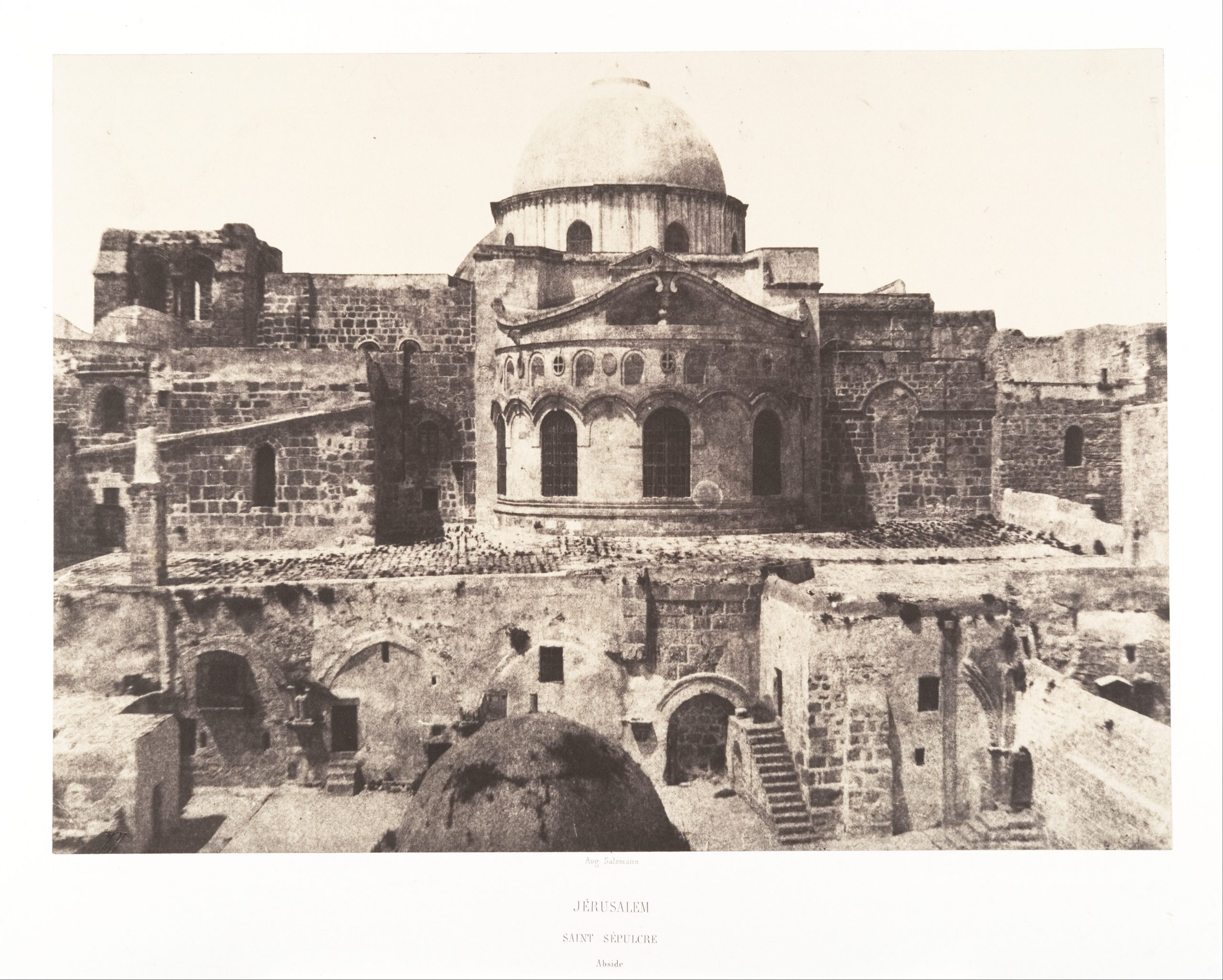

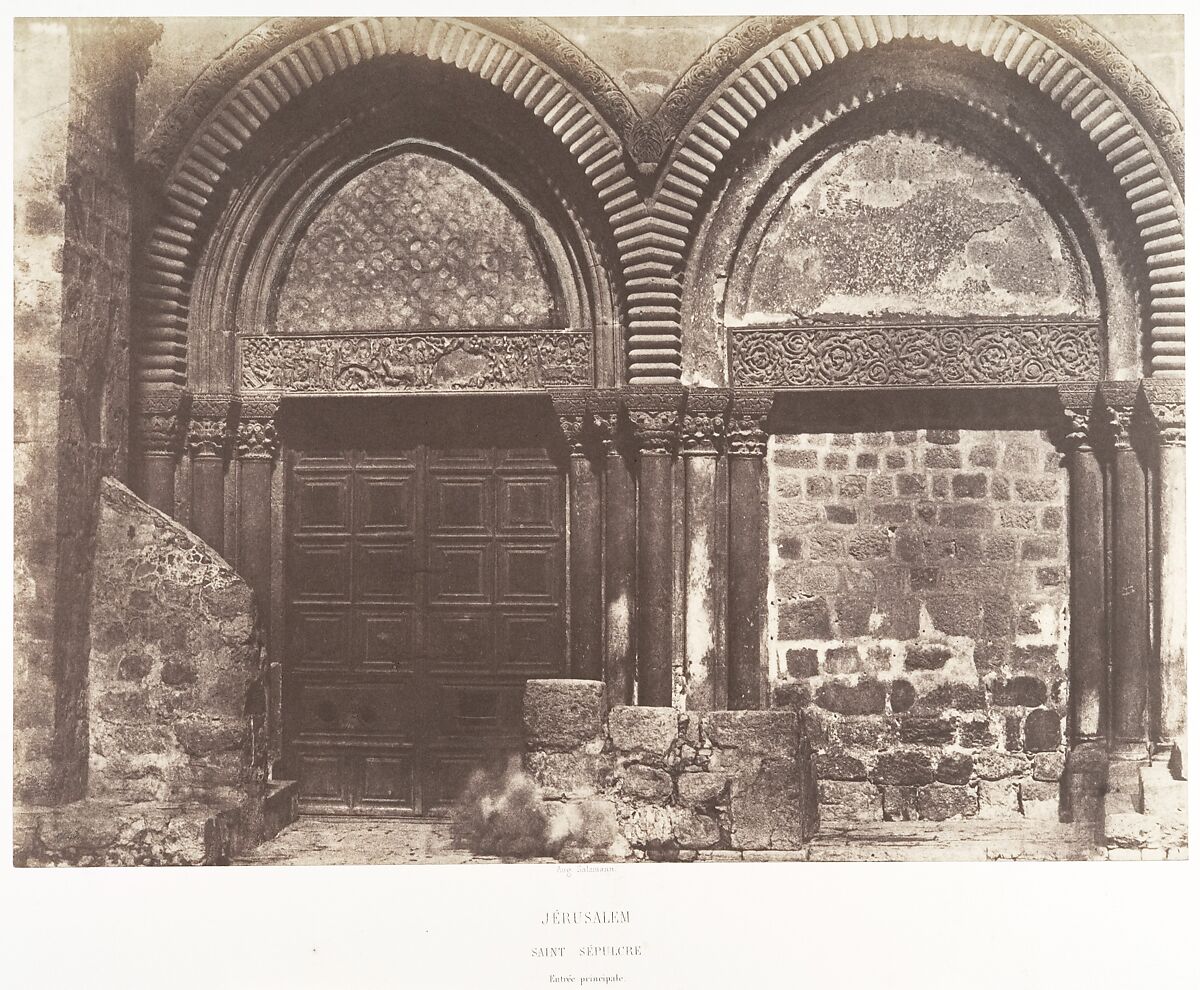

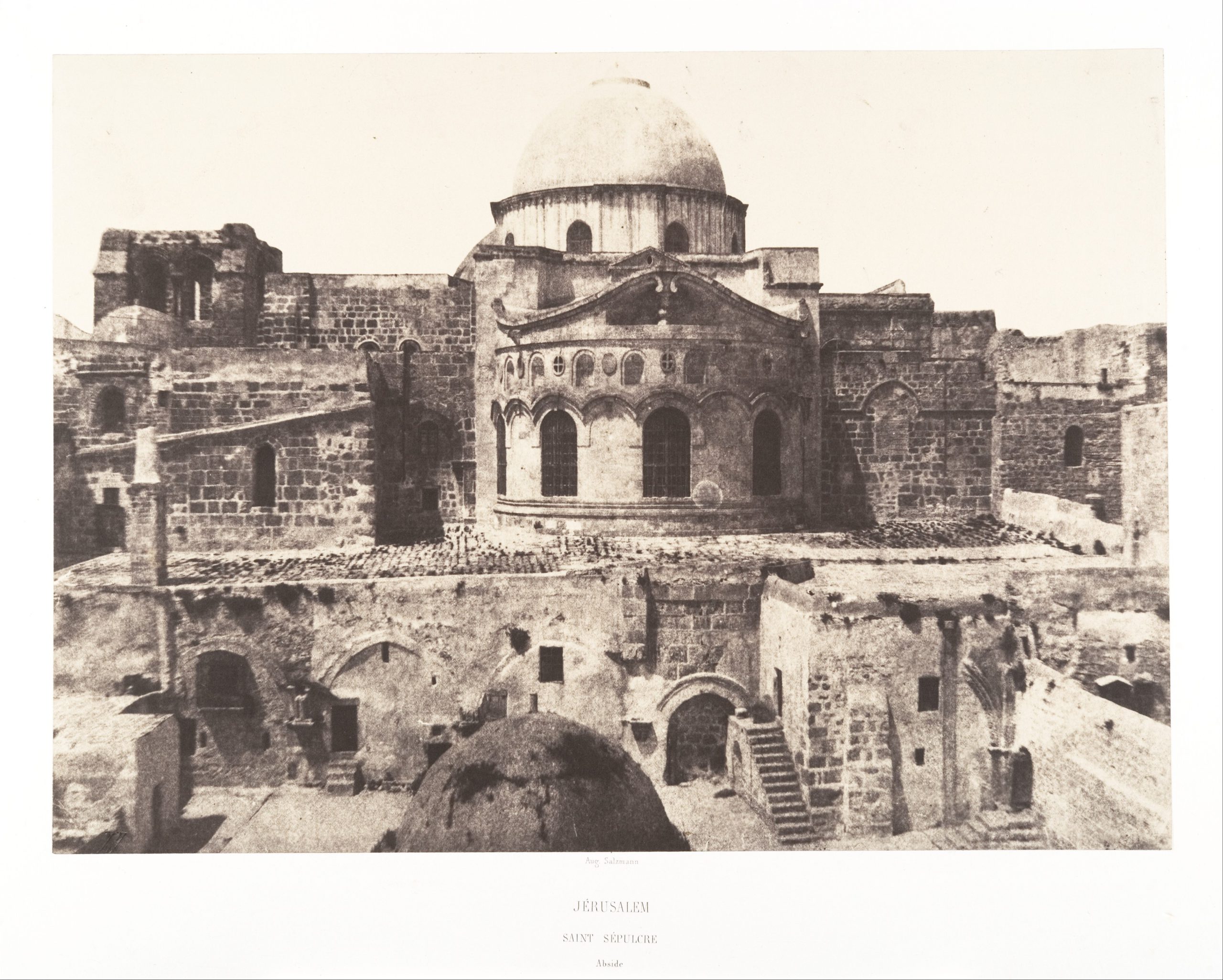

Holy Sepulcher, Jerusalem. Auguste Salzmann, 1854.

The Fatimid age of tolerance, at its height during the reign of al’Aziz, the great builder of Cairo, did not survive the caprices of his son Ali Mansur al-Hakim, raised to the throne at the age of eleven. A “frantic youth” (Gibbon), whose mother was a Russian Christian, Hakim did not mellow with age. “His reign was marked with monstrous atrocities,” Philip Hitti details.

He killed several of his vizirs, demolished a number of Christian churches including that of the Holy Selpulchre (1009), forced Christians and Jews to wear black robes, ride only on donkeys and display when in baths a cross dangling from their necks if Christians, and a sort of yoke with bells, if Jews.

In Egypt, where men and women had always mixed freely, none of Hakim’s innovations aroused such turbulent opposition as the strict confinement of women: according to Gibbon, “the restraint excited the clamours of both sexes; their clamours provoked his fury; a part of Old Cairo was delivered to the flames, and the guard and citizens were engaged many days in a bloody conflict.” Amidst such upheavals, the destruction of the churches of the Holy Sepulcher, built five centuries before by Justinian, horrified Europe’s Christians, and it must be said, Hakim’s carnage was thorough-going. Not only were the churches torn down to their foundations, the rocky cavern itself was broken up with “much profane labor.” Altogether, Hakim’s regime was a woefully prophetic one, anticipating the radical iconoclasm of the Arab Wahhabi in the 18th century, the stigmas of the Nazis in the 20th, and the prudery of the Taliban in the 21st. “Finally,” Hitti winds up the astonishing tale, “this enigmatic, blue-eyed caliph, following the extremer development of Ismailite doctrine, declared himself the incarnation of the Deity”; and was embraced as such by a newly organized cult, the Druze. Secular history records that Hakim was killed by assassins recruited by his sister, who wished to protect the succession of her son to the caliphate. The Druze, however, believe that he simply disappeared, closing forever the door of mercy behind him, and will reappear at the end of days.

Rather than mounting an expedition against Hakim (again following Gibbon’s account), the West turned its indignation against the Jews in their midst, whom a conspiracy theory blamed for his actions, and those who escaped burning were banished. Hakim’s earthly successors restored the ancient Fatimid tolerance. The sepulcher was rebuilt, the Easter miracle of fire (a “pious fraud,” Gibbon sneers) promptly resumed, and the pilgrims returned in numbers. But the Fatimids were soon replaced as Palestine’s overlords by the Seljuk Turks. Having overthrown the Abbasids whom they had formerly served as mercenaries, the Seljuks were now contending with the Egyptians for mastery of the Middle East; and they were neither as lenient as Baghdad or as tolerant as Cairo had been to their dhimmi subjects. Gibbon once more:

A spirit of native barbarism, or recent zeal, prompted the Turkmans to insult the clergy of every sect; the patriarch was dragged by the hair along the pavement and cast into a dungeon to extort a ransom from the sympathy of his flock…

These outrages were no more than Hakim’s. But this time Europe would show a “more irascible temper”: It appeared that “a new spirit had arisen of religious chivalry and papal dominion; a nerve was touched of exquisite feeling; and the sensation was vibrated to the heart of Europe.”

“No love of native heath should delay you, for in one sense the whole world is exile for a Christian, and in another the whole world is his country: so exile is our fatherland, our fatherland exile.” Here was the rationale for a thousand years of European adventuring abroad, without ever losing sight of heaven.

Beset by Turkish invaders in Asia Minor, disconcerted to find vagabond Normans occupying ancient Byzantine territories in Apulia and Sicily, besieged in Constantinople itself by needy aristocrats whose Anatolian estates had been lost to the Turks, the emperor Alexius I Comnenus established a détente with the Latin church. Might the Great Schism between Orthodoxy and Catholicism, which had arisen as recently as 1054, be repaired? In a fateful hour, Alexius authorized an appeal for military assistance to be delivered by his spokesmen at a church council at Piacenza, with the pope, Urban II, presiding. At a subsequent council in Clermont, in central France, Urban responded with his famous call for a crusade, promising heavenly grace to the cross-bearers (thus, “crusaders”) who went to the rescue of their oppressed brethren and achieved the restoration of the Holy Sepulcher: “Rid the sanctuary of God of the unbelievers, expel the thieves and lead back the faithful,” Urban exhorted—or at least he did in the eloquent version attributed to him by William of Malmesbury. “No love of native heath should delay you, for in one sense the whole world is exile for a Christian, and in another the whole world is his country: so exile is our fatherland, our fatherland exile.” Here was the rationale for a thousand years of European adventuring abroad, without ever losing sight of heaven.

Significantly, Urban issued his call not from Rome, which was inconveniently occupied by an antipope, Guibert of Ravenna, but from a conclave in his native France. In terms of soldierly manpower the Crusades would be a largely Frankish affair, invigorated by Norman bravura, but also manipulated along the way by Venetian cupidity (historically, the Serene Republic was the cultural offspring and nominal vassal of the Empire, but an ungrateful one).

In the chapter on the Crusades in his Short History of the World (1922), H. G. Wells presents its tragicomic opening, the so-called People’s Crusade, as perhaps the first truly democratic movement in European history. At the inception Urban saw a crusade as a means of diverting Europe’s “superabundant fighting energy,” from selfish “private” wars into a unifying mission based on a universal truce, “God’s peace.” If successful, it would compel the gratitude of Eastern Orthodoxy and, ideally, its theological submission to Rome. Peter the Hermit—not a recluse, but an itinerant fanatic who had made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem—added fervor to these cool calculations with harangues that stirred the barefoot multitude in northern France and Germany.

“Such a widespread uprising of the common people in relation to a single idea as now occurred, was a new thing in the history of our race,” Wells writes. “There is nothing to parallel it in the previous history of the Roman Empire or of India or China,” although such a collective feeling had been aroused on a smaller scale by the Hebrew prophets, Mani, and Muhammad. “The preaching of the First Crusade was the first stirring of the common people in European history. It may be too much to call it the birth of modern democracy, but certainly at that time democracy stirred.”

Here, the People’s Crusade would materialize in “crowds rather than armies,” would blunder and murder along the way, and would end “very pitifully and lamentably.” As many as 40,000 men, women, and children followed their uncouth shepherd, as they marauded their way to Hungary. There, exasperated at being mistaken for pagans and evilly treated, the recently Christianized Magyars had massacred two earlier waves of crusaders, and now reduced Peter’s numbers. At last, a remnant reached Constantinople, where it joined the flock led by Walter the Penniless. The emperor Alexius, who had anticipated a foreign legion and got, in the first instance, a rabble, was aghast. In August 1096, “complaints were already pouring in of robberies, rapes and lootings.” Unimpressed at a meeting with the Hermit, Alexius had the luckless multitude ferried across the Bosphorus to fend for themselves. At length fearful about where his followers’ zeal might lead them, Peter returned to the City, no doubt to plead for protection.

As related by John Julius Norwich, his leaderless followers continued to antagonize the local Orthodox Greeks with their crass behavior, “killing, raping and occasionally torturing” their fellow Christians, but probably not roasting their babes on spits, as rumor told. On October 21, they marched straight into an ambush, retreating in a panicky flight to their camp, pursued all the way by the Turks. Norwich:

A few lucky ones managed to take refuge in an old castle on the seashore, where they barricaded themselves in and somehow survived, as did a number of young girls and boys whom the Turks appropriated for their own purposes. The rest were slaughtered. The People’s Crusade was over.

The crusade of the princes was meanwhile massing its forces, possibly 150,000 strong by the time they were assembled by their feudal lords outside the gates of the City and ceremoniously greeted by Alexius. Among these characters destined to figure prominently, if not always gloriously, in the history of Byzantium and the Crusades were Geoffrey of Bouillon, Baldwin of Flanders, and, most vividly of all, Bohemond, the younger son of the Norman baron, Robert Guiscard.

In the emergent West of the 11th and 12th centuries, and especially in Byzantium, its most civilized part, there was nothing but reversals of fortune.

On the Byzantine side, the story is told by the emperor’s daughter, Anna Comnena, whose eulogistic history of her father’s reign, the Alexiad, is a unique document in the annals of empire; only completed on her death-bed in 1153, it has been claimed to be the first major work of history written by a woman. Gibbon accuses Comnena of having an over-elaborate style that “betrays in every page the vanity of a female author,” which is not only ungallant but unworthy. The princess was justifiably proud of the superb education she had received, mostly at her own insistence, as well as the extent of her researches; and it is true her style might strike a modern reader as excessively rhetorical, but it was also equal to diplomatic combinazione: battles at sea, riots in the capital, the insatiable ambition, ferocity, and blond-beast good looks of the Guiscards of Apulia. The Alexiad ranges far beyond the Blachernae Palace and its intrigues to Comnena’s father’s interminable campaigns, conveying a sense of plebeian discontent and far off shadowy figures: Turks, heretical Bogomils, restless territorial Normans, always with designs on the heavenly city. In the emergent West of the 11th and 12th centuries, and especially in Byzantium, its most civilized part, there was nothing but reversals of fortune.

In spring 1097, now leading a disciplined and well prepared army, the princes crossed the Bosphorus into Asia. Their line of march took them past the ghastly sight of the people’s whitened bones piled in heaps and left to the elements. Fortune favored the bold. Following the approximate route Alexander had taken into Syria 1400 years before, and Napoleon would partially retrace 800 years later, the crusaders took Edessa and Nicaea, the provincial capital of what the Seljuks called “al-Rum” (meaning Rome and pronounced “room”), and devastated the Turks in a pitched battle near Dorylaeum in deeper Anatolia.

“This victorious march,” writes Hitti, “restored to Alexius, who had exacted from almost all the Crusading leaders an oath of feudal allegiance, the western half of the peninsula and helped to delay the Turkish invasion of Europe for a century and half.” There followed the campaigns under the Normans Bohemond, Baldwin, and Tancred, and Raymond of Toulouse, in which the first Latin baronies in the Middle East were established—the months-long siege and occupation of Antioch, where Bohemond would proclaim himself prince, followed by entrance into Palestine and arrival at Jerusalem.

Hitti continues: “Hoping the walls would fall as those of Jericho had done, the Crusaders first marched barefoot around the city, blowing their horns. A month’s siege proved more effective.”

Inside the gates, the crusaders made the holy city a charnel house: all the Muslims they could find were slaughtered and the Jews were burned alive in their synagogue. The chronicles tell of streets coursing with blood in which the Christian soldiers splashed as they rode. “At nightfall, ‘sobbing for excess of joy,’ the crusaders came to the Sepulchre from their treading of the winepress, and put their blood-stained hands together in prayer. So, on that day of July, the First Crusade came to an end.”

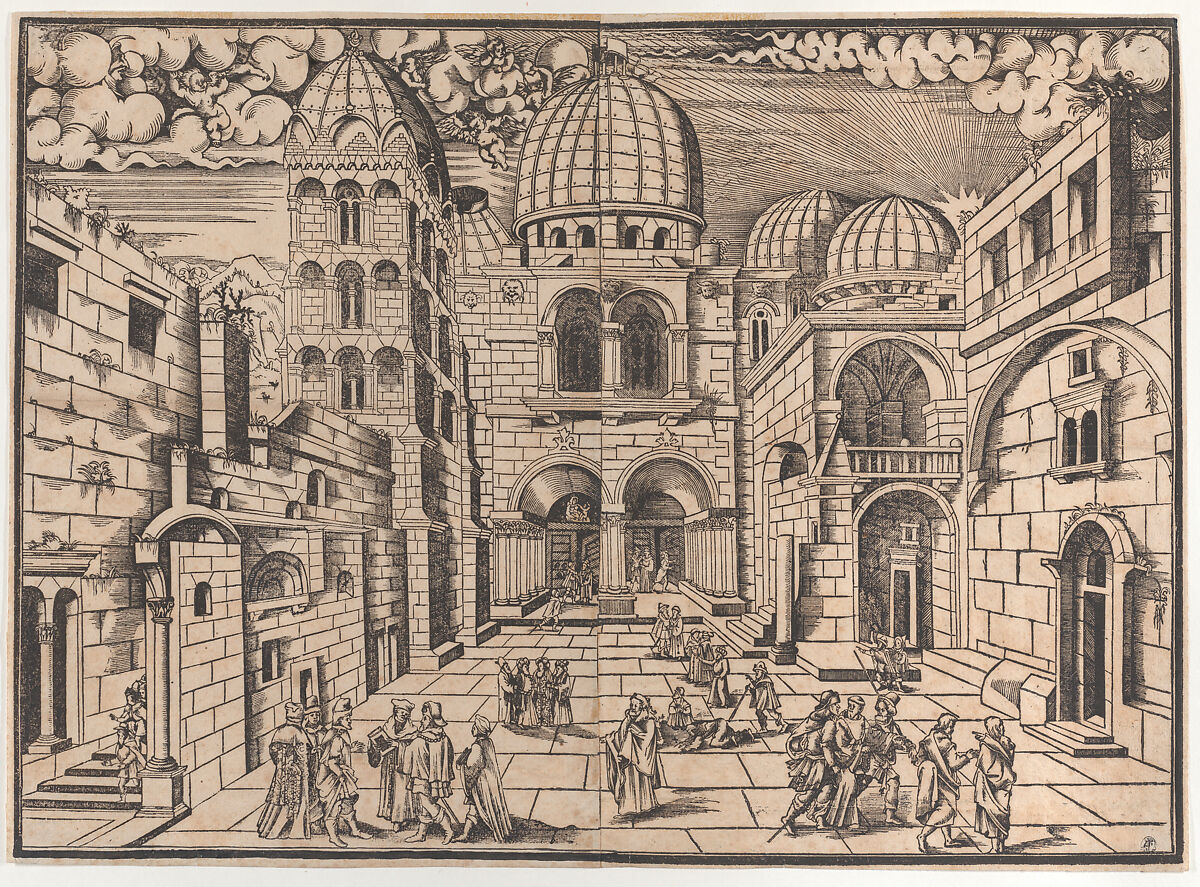

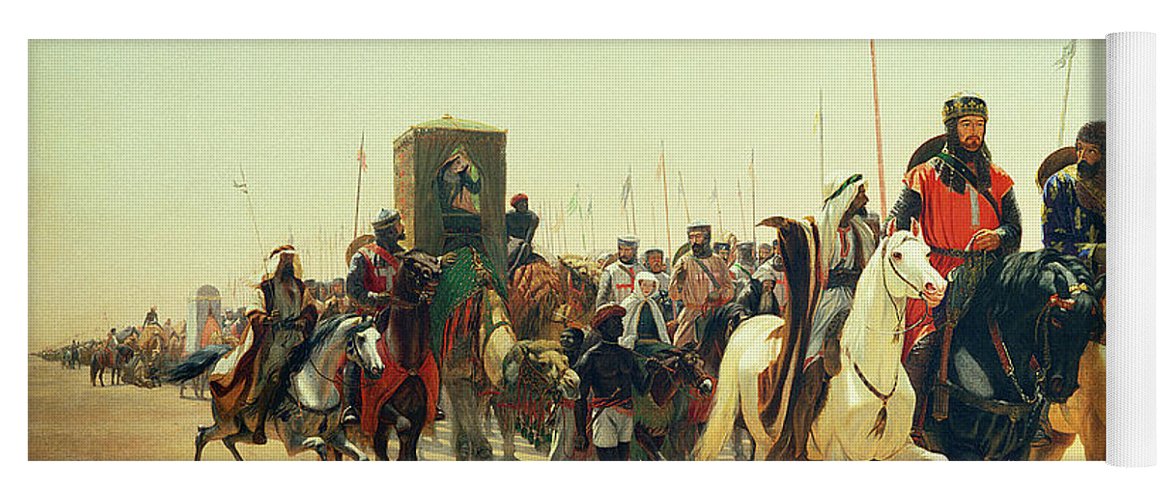

Richard the Lionheart on his way to Jerusalem, James William Glass, 1850.

Ruled initially by Geoffrey and then Baldwin, in its various forms Jerusalem would be the most enduring of the Crusader states, lasting some 200 years, and claiming at its peak approximately the territory of present-day Israel, while hugging the coastline all the way to Damascus.

“Contrary to the expectations of many, the First Crusade turned out to be a resounding, if undeserved, success,” John Julius Norwich summarizes. The early 12th century proved to be an excellent time for a European invasion of the Middle East. The possession of Syria and Palestine was being contested by the Shiite Fatimid caliphate in Egypt and the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, both powers on the wane. Their proxy wars were fought over the heads of an immemorial peasantry that occasionally indulged a mutinous spirit (there were the usual plagues and famines). As intruders and transient overlords the red-haired barbarians were just another nuisance, perhaps even a diversion. The ancient empires were slow-breathing, long-lived entities; the Crusader kingdoms waxed and waned in mere decades, becoming a byword for transience. A second Crusade, in which German knights were prominent, was mounted in 1147. It culminated in a failed siege of Damascus in 1149.

The stalemate was theatrically broken in the 1160s by the Kurdish general, Salah-ah-Din, known to the West as Saladin, who burst upon the scene as the young conqueror of the enervated Fatimids—their dynasty died out in a series of boy caliphs, some as young as four and five—and as the romantic antagonist of the Crusaders. His army men tore down the golden cross on the Dome Rock, on October 22, 1187, eight decades after the Christians had taken Aqsa Mosque at a cost of 70,000 Muslim lives.

To this enormity the West replied with a unified front led by Frederick Barbarossa, the emperor of Germany (who unluckily drowned in a river in Cilicia on his way to the Holy Land), Richard the Lion-Heart, the Norman king of England, and Philip Augustus, the king of France. The Third Crusade, although it accomplished not much more, became and remains the matter of romance and legend. The heyday of chivalry was succeeded by a triumph of venality. A Fourth Crusade, mounted by the usual French princes in 1203, and destined for Palestine, was diverted with suspicious ease by the Venetians, led by the 90-year-old blind doge, Dandalo, into meddling in Byzantium’s usual dynastic intrigues—feuding brothers, scheming widows, mob scenes, blinded young princes—finally using the excuse of a riot in 1204 to occupy and ransack the City, defile Santa Sophia, the greatest church in Christendom, and install as emperor a crude Latin prince, Baldwin I, who, adorned in the imperial regalia, ascended the throne after an orgy of desecration, destruction, and mass rape.

The Children’s Crusade of 1212 was a pathetic affair, led in France by a youthful shepherd, Stephen of Cloyes, and in Germany by another youth, Nicholas of Cologne; their followers, possibly including deluded adults as well as boys, expected the sea would part for them when the time came. The masses paused, respectively, in Genoa and Marseille before their destruction.

“Stephen’s army was kidnapped by slave-traders and sold into Egypt; while Nicholas’s expedition left nothing behind it but an after- echo in the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.”

No doubt, the slave-markets of the East, extending all the way to Baghdad, were capacious enough to swallow up without a trace both boyish armies. Pope Innocent, nursing the dream of a universal empire under the tutelage of a universal church, obliviously moralized, “the very children put us to shame; while we sleep they go forth gladly to conquer the Holy Land.”

Crusades of a sort continued to be proclaimed, and even to be mounted, in the East for another two centuries; but their great age had passed. After some desultory back-and-forth, Jerusalem was restored to Muslim rule in the mid-13th century, where it remained for more than 600 years. Their haunted castles were the last remnant of the Crusader kingdoms. Western Europe’s Age of Empire waited upon time and tide.

Sources:

Ernest Barker, The Crusades. London, 1966, a reprint of the article on the Crusades in the 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1910-11).

Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. J. B. Bury text, 1898.

Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs. London, 1951, 5th edition, revised.

John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. New York, 1996.

J. M. Roberts, The Pelican History of the World. London, 1987, revised edition.

H. G. Wells, A Short History of the World. 1922; rpt. London, 2006.