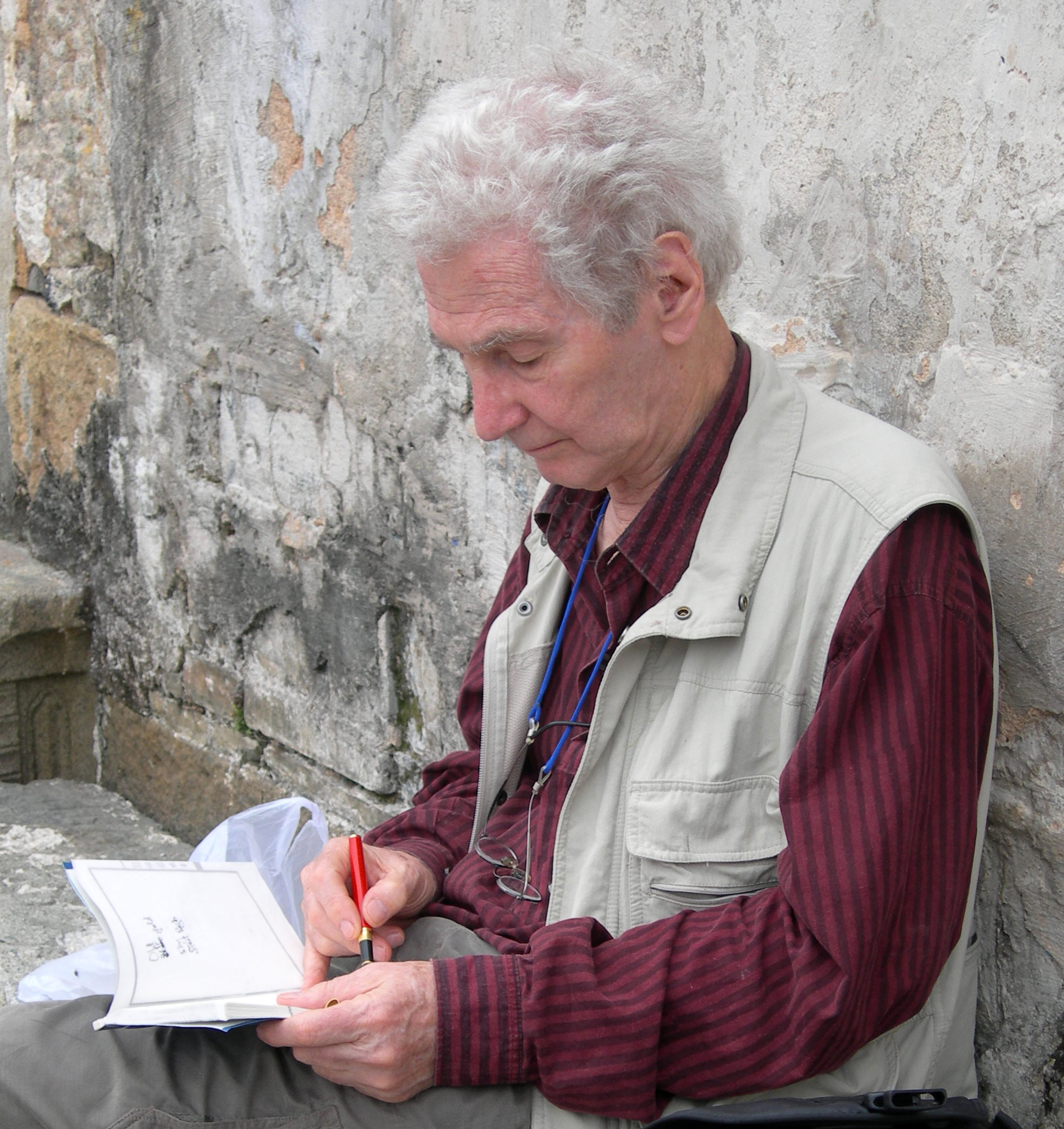

Poet, translator, painter, polymath Willis Barnstone lives in a one-story clapboard house on a quiet tree-lined street off Pleasant Valley Road in Oakland, California. Barnstone’s voice is a delicate tenor, bashful on approach until eagerness overcomes him and he begins showing us his latest watercolors. His home is warm and welcoming, decorously overflowing with the art objects and ephemera he has collected—together with his partner, the Chinese art historian Sarah Handler—through many years of travel. Along with a new translation of Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal, he has been at work on vividly colored line portraits of famous figures in history (Cervantes, Shakespeare, MLK, etc.)

We are talking about Jorge Luis Borges when we start recording. Throughout, the flow of conversation is interrupted, shaped and punctuated by Barnstone’s many worldly digressions. Ms. Handler is always graciously there to assist and prod the conversation along. He shows us the photographs he took for the Saturday Evening Post and Holiday Magazine, his many more paintings and watercolors, his photographs of Borges, the many varieties of hand-carved sculpture from various cultures—ancient Chinese date unknown; an armless Filipino Jesus. All while we sit and chat he gets a call from a friend, reminisces on fallen friends, mis-hears a good deal, and carries himself with such great vitality, enthusiasm, and wonder that occasionally the two of us wonder if we’ve been taking this whole business of words and language too soberly. For Barnstone, who turns 97 later this year, remaining light-footed and open-hearted are the keys to posterity. This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Willis Barnstone's first teaching position was instructor in English and French at the Anavryta Classical Lyceum in Greece, 1949–50, a private school in the forest of Anavryta north of Athens, attended by prince Constantine, the later ill-fated king of Greece, who was then nine years old. In 1951 he worked as a translator of French art texts for Les Éditions Skira in Geneva, Switzerland. He taught at Wesleyan University, was O'Connor Professor of Greek at Colgate University, and is now Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature and Spanish at Indiana University where he has been a member of East Asian Languages & Culture, and the Institute for Biblical and Literary Studies. He started Film Studies at Indiana and initiated courses in International Popular Songs and Lyrics and Asian and Western Poetry.

His center is poetry, but his books range from memoir, literary criticism, gnosticism, and biblical translation to the anthologies A Book of Women Poets from Antiquity to Now, 1980 (with Aliki Barnstone) and Literatures of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, 1998 (with Tony Barnstone), and collections of photography and drawings. Funny Ways of Staying Alive, Poems and Ink Drawings, 1993, contains 103 dry brush drawings. His New Faces in China, 1973, a volume of photographs and facing poems, reveals China during the catastrophic Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Children play and smile wildly while austere adults, in identical prison-like attire, sit on the pavement in empty Tiananmen Square. In 1966 he founded and was director of Artes Hispánicas/Hispanic Arts, a slick, bilingual journal of Spanish and Portuguese art, literature, and music, published biannually by Macmillan Books and Indiana University. Two of its issues were published simultaneously as trade books: The Selected Poems of Jorge Luis Borges, guest editor Norman Thomas di Giovanni, and Concrete Poetry: A World View, guest editor Mary Ellen Solt. In 1959 he was commissioned by Eric Bentley for the Tulane Drama Review to do a verse translation of La fianza satisfecha, an obscure, powerful play by the Golden Age Spanish playwright Lope de Vega; his translation, The Outrageous Saint, was later adapted by John Osborne for his A Bond Honoured (1966). In 1964 the BBC Third Programme Radio commissioned him to translate for broadcast Pablo Neruda's only play, the surreal verse drama Fulgor y muerte de Joaquin Murieta (Radiance and Death of Joaquin Murieta), which was also published in Modern International Drama, 1976.

A Guggenheim fellow, he has four times been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, and has had four Book of the Month Club selections. His poetry has appeared in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, Poetry Magazine, The New York Review of Books, and The Times Literary Supplement. His books have been translated into diverse languages including French, Italian, Romanian, Arabic, Korean, and Chinese. Barnstone lives in Oakland, California, with his wife Sarah Handler. A full-time writer, he gives poetry readings, often with his daughter Aliki Barnstone and son Tony Barnstone.

WB: …left him with no vision in one eye, and a little bit of vision in the other. He could hardly see color, but he remembered colors.

DM: When did you first meet Borges?

Do you know the Young Men's Hebrew Association (YMHA) on 102nd Street and Lexington Avenue? Every week they’d have a great writer or painter, and one day they had Borges, and afterwards I went up on stage and spoke to him in Spanish. I said that I had done a book on Machado and he said, “El Bueno or El Malo?” Bueno was Antonio, because he was on the Republican side. And of course Borges mixed them all up intentionally. He was always horsing around. But his speech was as poetic and significant as when he wrote.

His speech was like his writing.

If anything, it was better. I knew him for twenty years. I spent a year with him in Buenos Aires and I invited him to Indiana for a semester each time. When I took him to the University of Chicago Institute, a doctor told me, “I can cure him with a simple operation.” Borges refused. I often have nightmares that the doctor could have cured him. Being blind, he saw everything. When I was in Buenos Aires, I lived across the street from him and his wife, María Kodama. One day, Borges knocked on my door and said, “Barnstone”—he always called me Barnstone—“What does María Kodama look like? She tells me she’s very lovely.” And I said to him, “Borges, you’re a fool. She’s beautiful and you don’t deserve her.” I always teased him. Everybody flattered him and he couldn’t stand that.

Can we ask you some questions about The Poetics of Translation?

Yale told me it’s being translated now into, of all things, Spanish. I heard about that about 6 months ago—

You heard? They didn’t ask you?

They own the rights. They just told me.

You talk about translation as an art form. Can you talk about your philosophy of translation as art and why you believe it is an art unto itself?

I think translation is a creation. The word “translation” is from Latin, “translatio,” meaning to move from place to place. It’s just a continuation. You expand the English language—or any language—by having a translation. The very act of speaking is a translation of mind into talk.

You quote Octavio Paz, “Everything is a translation.”

Everything is a translation. We stop translating, we’re dead. We have to move.

You also said that language is infinitely changing.

To stay alive, it has to.

I think translation is a creation. The word “translation” is from Latin, “translatio,” meaning to move from place to place. ... The very act of speaking is a translation of mind into talk.

Translation of old texts brings the spirit, the beauty of the original text to the present, and that is continuously changing. When and how were you first drawn to the Bible for translation?

When I was a kid, my parents didn’t know much about religion, but we were Jews. All the [Bible] stories are fake, but so what? We don’t really know much about them. The Third Millennium is the first time we hear about the Jews. They didn’t schlep stones to build the pyramids, because the Egyptians were a few millennia earlier. But you wonder what kind of religious texts they had before the Bible was there, or what held them together. In Antiquity the Jews were twenty percent of the population, now they’re one half of one percent.

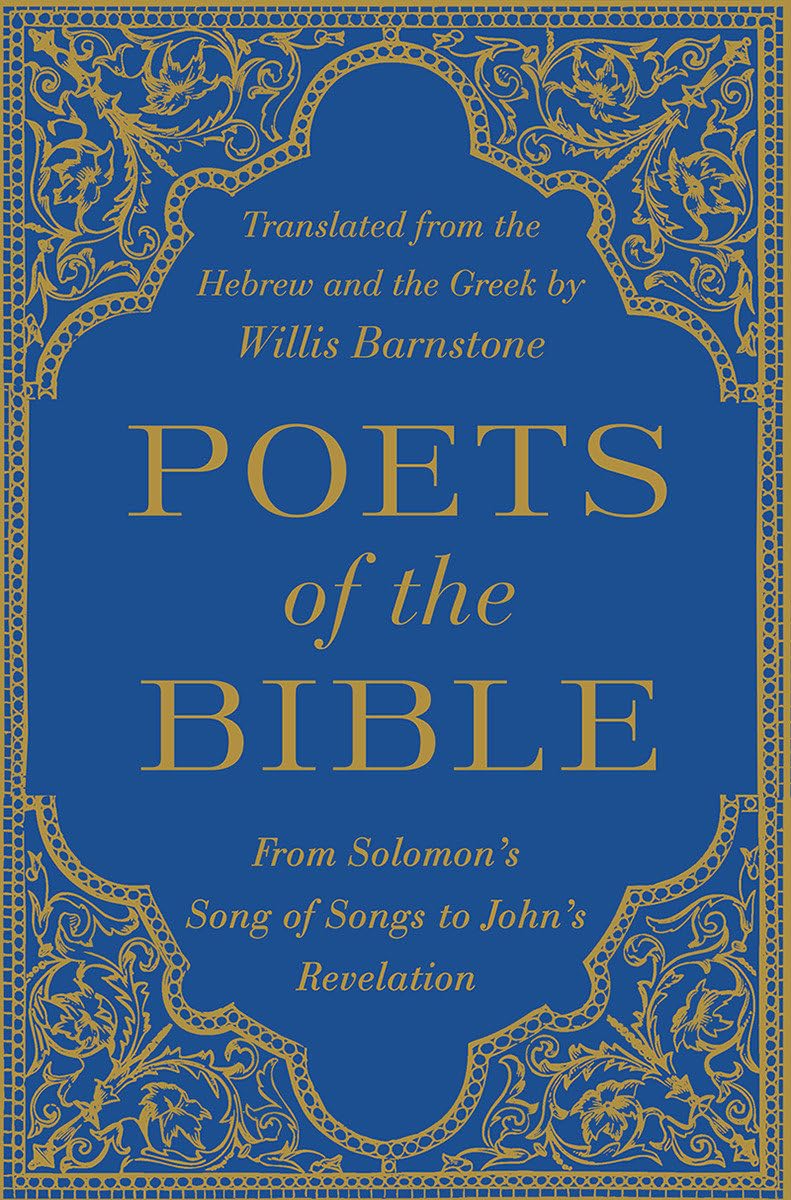

As you may remember, the normal form in Hebrew was two lines, and then a repetition of them, pushed over a little bit—that is, the same thing said differently. Which is an interesting way of getting the message across. I loved doing Poets of the Bible.

As a translator, do you find that you internalize the original work, by knowing it well, so that when you sit down to compose, you’re writing a poem in its spirit? Or are you doing direct text-to-text comparison.

I want to be close to the words. I want to know them as much as I can, and know their possibilities. I think the original poet has to be respected, but I think it doesn’t matter if the translation is close or far, so long as it’s good.

You write about Edward FitzGerald. He didn’t respect the original Persian Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

What makes you say that?

You said that. In The Poetics of Translation, you say he had this “bright arrogance” where he took the original Rubaiyat and basically made a new one for Victorian England. It was very popular, but totally different from the original. You’re talking about the respect for the original, but he disregards the original and makes a new text.

(Barnstone struggles to recall this specific conceit so Handler looks for the book so we may point out the quote. A few minutes pass within which Barnstone says, among other niceties, “I want to tell you something. We’ve been isolated for a long time, and it gives me great happiness to find people who are interested in what I did.” Then, finding the page, he reads what he wrote about FitzGerald’s bright arrogance and says, very dryly, “It’s pretty funny.”)

SH: Do you still agree with it?

WB: A translation can be an improvement on the Rubaiyat, and that would be a typical Borgesian notion, that the original is just a mere imitation of the translation. He didn’t say that, but that’s the kind of thing he would say.

Do you have any favorite translations or translators? Ancient, modern, contemporary?

I’m out of touch with contemporary, unfortunately. I never was able to get a subscription to Poetry. I kept sending them money, and they never sent me the magazine. I knew the editor quite well.… You know, when I used to go, with great pleasure and slight displeasure to the Translation Society, and they gave me a plaque—which I have over my desk, for "Life Achievement"—but it was run by a bunch of gangsters. They were mediocre poets and kept giving the prizes to themselves. You couldn’t translate a pinball machine into a sewing machine. They were hopeless. I can tell, if I read two lines, if a person is good or bad. The lines have to be good—I don’t care if they’re accurate or not. It would be nice if they’re accurate, but they have to be good. The method doesn’t matter so long as it’s quality.

Did you rate Lowell as a translator in Imitations?

I thought Lowell was fantastic, whatever he did. I remember he went to Buenos Aires once. The first thing he did was get in touch with Borges, and Borges tells me, “Who’s this curious American poet who walked in. He was very knowledgeable. We had fun. And then suddenly he began to scream, lay on the floor, and pulled his trousers down.” And I said, “He’s a wonderful poet but has episodes of madness.” Borges said, “I don’t care what you say, so long as he keeps his trousers on.” I met Lowell. He was a superb translator. His first book about the Atlantic coast—

Land of Unlikeness?

—I don’t think he ever achieved again what he did in that first book. It was kind of surreal, yet very, very earthy and salty and balmy.

—Ah, Lord Weary’s Castle, the second book.

Even the title. It’s beautifully decadent.

Good poetry is always song. And good poetry began with form as a way of remembering, because they wrote poetry before they could write. Song precedes writing.

You’ve written a lot of sonnets. I’m thinking of those in The Secret Reader: 501 Sonnets. Can you talk about the sonnet form? You and Borges said that the form of the sonnet should be invisible.

I like to make the form not clang. When I was writing those sonnets, I got to the point where I’d take a shower and I’d think of two sonnets at the very beginning, and I’d remember the rhymes and I’d sit down and write them. I wrote many of them as fast as I could write, with all the care and discipline I was able to assume. I had more joy writing that book than any other. That doesn’t mean it’s good or bad.

You know, the sonnet supposedly came from Southern France. But there were earlier sonnets in Sicily, until the head of the Roman Emperor, who himself was the best poet around. And those were just wonderful. The sonnet means little song. A modest name.

That’s why they’ve always been a perfect vehicle for confession, and a declaration of love. They’re very personal in that way.

They were songs. Good poetry is always song. And good poetry began with form as a way of remembering, because they wrote poetry before they could write. Song precedes writing. I don’t think it’s true, as some people think, that the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed aurally and then later recorded. But there’s no way of knowing the truth.

You were in China during the Cultural Revolution, is that right?

I had translated the poems of Mao and wrote a telegram to then Premier Chou Enlai saying I’d translated the poems of Mao and we’d like to visit China. And within twenty minutes I got a telegram back from him saying to go to Ontario, Canada to pick up a visa for five people.… So, ten days later I was in China with four people, none of whom knew a word of Chinese, but we had fun. After we crossed the border from Fragrant Island, Hong Kong, they put us in a big room for four hours. We were starving, and suddenly six waiters came in, dressed like English lords, and served us food. That’s how we got to China. Everybody stayed for two weeks, and then went back. I didn’t have to go back, because I had the semester off, so I stayed for three months. They didn’t have American currency. So I could go to any place, get on any plane. There was saw dust on the floors of planes then. And the women who took care of you—the hostesses—were barefoot.

This was in 1972?

The book came out in 1973, so I must have been there in ‘72. Indiana University Press did this book in less than a month, and that was before computer days. When I was going to China, I had already done the book of poems of Mao. They put my Mao book out in less than a week.

How was the book of Mao poems received?

They didn’t have it in China, but it was in Hong Kong. It sold thousands. The biggest mistake the English made was to not make Hong Kong a separate country like some of the other separate countries there.

A few years later, in 1977, you published China Poems.

I haven’t re-read it since I wrote it.

In one of the China poems, you talk about your time in Greece, and how you were reading the Tang Dynasty poems in Greece. This was before you visited China. You write “I’m looking with my book for Du Fu’s Yellow Mountains / shining like oil lamps at night.” What did the mountains look like when you saw them in real life, that is, outside of language?

It’s the same thing as a vision. The main thing, you know, as with all kinds of idealistic things, is that when we got up on the mountains, we found that they didn’t have any toilets, so people were taking a shit right on the top of the most holy place.

When did you first go to China? Was that in '72?

In 1972. We were in the middle of the Cultural Revolution. And you know the woman behind it was Mao’s wife. Mao himself was dying of syphilis and a dozen other things, but you know, when I asked to speak with Mao—there were only seven other foreigners in China at the time—the authorities always said he was with the people. But he was actually dying. And his wife was taking over, the so-called Gang of Four. So when Sarah and I met in China, it was the most liberal period, and everyone was getting more and more optimistic. Prior, Mao had forced everyone—men and women—to look alike.

Why did you translate Mao?

Because I heard that Mao was the best poet. But it’s very easy to be the best poet when everyone else is excluded. He wrote in traditional Chinese poetic form, and he didn’t allow anyone else to publish in that kind of form. I was happy to be in China in those days.… Today, China has gotten rid of the worst of its poverty, it’s true. But the executions continue. Just like in Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Beyond the Chinese Revolution, you found yourself in Buenos Aires during the Dirty War, and you were in Greece following the Civil War. You’ve been in many different places when events were happening—

It’s nice to be in a country where everything is going wrong because you immediately become friends of the hurt people.

Was this coincidental, or were you pursuing this? Did you find yourself in history or did history find you?

It was an accident. I married a Greek so I went to Greece. The war was ending when I went to Mount Athos. I had an escort of three policemen on horseback in front and I was on horseback and they pointed there and they said, “Those are guerillas and there’s no point in shooting at them because they’ll shoot back at us.” I spent a month at the monasteries in Mt. Athos, the medieval center of Greek and Russian Orthodoxy. You go from one to another, usually three or four hours away. It’s on a big peninsula in North-East Greece, high in the mountains. Depending on the monastery, they would make icons and sell them to the people who visited. It was very hard to get in there, but who knows what’s going on today. I think there are very few monks in Greece now.

What was it like studying at the Sorbonne?

Beautiful. The professors were so articulate and when they read the poems—whether it was Rimbaud or Verlaine or Apollinaire—they read like no other people could. They were not actors. In those days, the world was small. I wrote to Camus and I told him about my Spanish background, and he immediately answered—the letters are in the Lilley Library at Indiana and the Library of Congress—and he only learned French when he was 8 years old. His mother was a Spaniard and his father, who was French, died in the First World War on the first day of combat. So Camus grew up speaking Spanish.

Which of the French poets have you translated?

I haven’t published it yet, but I’ve done the complete poems of Baudelaire, all in rhyme, and my rhyme is not banal. It reads like prose, but it’s lyrical.

Did the French poets influence your poetry? Not your translations, but your own poems?

Everybody influences me.

In terms of Baudelaire. He’s not mean, or arrogant, or derogatory, but he’s—

—Oh, he can be mean. For example in Les Fleurs du mal, in the first ten pages, he talks about Jews as three-legged beggars, who will cheat you at every moment. When he died, in the last ten years of his life—he only lived to be about 46 or something—his best friend was his doctor, who was a Jew, and who supported him. He had no income at that time, he was in exile in Belgium!

Do you find that, especially with these cultures, like the French or the Spaniards, effectively Christian nations, that the antisemitism stemmed from the Christian interpretation of the Bible?

Anti-semitism comes from the New Testament. All of it comes from there. The Jews are on every page and every one of them is represented in the so-called Book of Love as a thief, a liar, and a hypocrite. It’s not a nice book of love. It’s a book of hatred. And Anti-semitism hasn’t disappeared.

On the subject of love, I wanted to ask you about Sappho. You’ve written many translations and editions on Sappho. When did your interest in Sappho begin?

I think it happened after I went to Greece. Sappho gave us lyric poetry. She gave us the meters we use for poetry. They tried to wipe her out over and over again. But her fragments remain. And the fragments are more modern than antiquity. And she had daughters, but she was clearly bisexual. There’s no fragment by Sappho that is not beautiful. And I don’t like other translations but my own.

Can I ask you about some other translations by Ann Carson and Dianne Rayor? I wanted to ask you about a specific line where you’re all very different. It’s your word choices in Fragment 31.

Ann Carson is a very good poet. She got a lot of prizes and so forth. I knew her, I believe. And if I’m not mistaken, she’s married to a Greek in Athens. And she knows her Greek, but I don’t like her translations.

You write, “You speak softly and laugh in a sweet echo that jolts the heart in my ribs.”

That’s nice.

It is nice. Those are your words.

Well, it’s Sappho.

The word “rib” is where your translation is very different from the others. Ann Carson says, “chest.” And Dianne Rayor says “breast.” But you say “rib.”

Of course.

Why?

Well, it’s much more anatomical. It’s stronger. “Breast” is a very romantic word.

That brings us to an interesting point you’ve made about fidelity versus friendship among translators and the source text. The job is not necessarily always to be true to the words as they were written, but more in the spirit.

Well, it depends. You know, the best translations are closer and closer to the spirit. If you’re good with language, you can do it any damn way. But if you’re not an artist, no matter what you do, you’re not going to make it. So, to use a cliche, there are many ways to Rome.

But do you find that, for example, using “breast”—is her connotation too romantic? What are these choices, where do they come in?

Read Ann Carson’s line again.

“Oh, it puts the heart in my chest on wings.” And then Dianne Rayor says, “My heart flutters in my breast.”

It’s a cliche.

She’s using a cliche.

It’s terrible.

And, you use the word “jolt”—it “jolts the heart.” There’s the grip of love in that word.

It’s gotta knock you out. It’s not going to flutter in your breast. Holy shit.

What do you think of Ezra Pound?

He’s a pain in the ass. He’s a terrible poet. I kind of know him, because his publisher, James Laughlin, the publisher at New Directions, told me about the last days that he took Pound around after they let him out of the nuthouse. Every day for years he ranted against the Jews. Not once, but everyday on the radio. And it was the Jewish lawyers who saved him from execution when he came back. I like the last poems in the Cantos and the early ones, which are really translations from the Anglo Saxon. He did know languages. He did compose an opera or something. He was talented but was lousy. Who can read them? Terrible.

What about his translations of the Chinese?

It’s not even Chinese. It’s Japanese. He’s a fraud. He knew French because he lived in France. He probably knew something of Spanish and he maybe knew Anglo Saxon. It was Borges who knew all of the extant poetry in Anglo Saxon by heart. There’s nothing he ever forgot. A friend of mine asked him about a Romanian poet who had a little success at one point. And he said, “Oh yes, when I was eight years old, living in Geneva with my parents, I saw some so-called fairy tales written by a person, and he quoted him. And my friend said, “It’s exact! How does he know it?” I mean that’s the way he was.

That’s a bonafide genius.

You know, half the time this type of genius does nothing, they’re kind of idiot savants. I had a friend, he was kind of sad. I went to a Quaker boarding school—the George school—then I finished up at Exeter, and my friend—he died quite a few years ago—he went through four years of algebra in the first semester and then coached the professors. He never did anything with his life. He was so naive.

What about Kenneth Rexroth?

I like his translations best. He didn’t know any Chinese or Japanese, but that doesn’t matter, they read as independent poems. … He was a crazy guy.

When you learn new languages, you meet new people, you see the universality of community.... Most Americans, when they see someone, they only want to talk about how great they are. But if you’re interested in others, it’s better for you. It’s natural.

In the peak of your career—in the 1950s, 60s, 70s—the literary establishment did not view multiculturalism the way you did, which is that the difference between Eastern culture and Western culture is very porous, non-existent, a series of cross-pollinations.

I was partly recognized, but no one had the expertise in such diverse places. I have an incredibly good ear for languages, which has been helpful. For example, when I went to Russia with Sarah, I studied Russian for three months so that I could say a little bit. But my accent is always good, so people think I’m much better. Even when I went to Kenya, I studied Swahili, which most of the tribes were able to use. A hundred, two hundred words can get you by.

It seems that your interest in all these cultures, and absorbing the poetic unity, is tireless. How did you become so well versed in different cultures and languages?

Every summer, while I was teaching, we had four months off, and I was always abroad. I lived there. That’s why. Then I went on a Fulbright to Buenos Aires and spent a year with Borges there. I went to Spain for a year. I went to Greece for many years. I’ve been going to France since I was 20. Many trips to China. I only spent 4 days in Japan. I was amused and awed because everyone was so nice and helpful and honest.

Would you say that your contemporaries at that time lacked curiosity? Because the literary establishment of the 1950s and 60s were not publishing what you were publishing.

When I was in China, there were seven other Americans there. One was a scientist. One was a dentist. And the other five were astronauts. There weren't any other writers there at that time. They weren’t invited. It was only because I wrote the Poems of Mao. I don’t think anyone was able to travel there. If you’re nice to people, and don’t act suspicious, they’re always very happy.

Your anthology, A Book of Women Poets from Antiquity to Now—

—which I did with my daughter—

How did that come about?

Well, I thought women were not given their fair share. That’s the main reason. So many of the great poets—including Sappho as the first lyric poet we have—were women.

I have a question that’s very specific. It’s about word choices. Something I noticed is the word “loaf.” As a verb, “to loaf,” a loafer. And I noticed it again and again in your sonnets.

It’s from the French, the notion of loafing. It’s Walt Whitman who talks about loafing. And it’s also about the French—the flaneur.

You use it at least 4 times in your sonnets. And then it’s also in your China Poems. And when you’re talking about loafing, it’s always about reading and writing as an artist. I love that word.

It’s a strange word. It’s not a modern word.

But this idea of idleness. To be idle.

It’s not in the modern American world at all.

Taking this term—to loaf, to idle, to wander, and also to produce poetry. You’re a traveler, you’ve been around the world—do you find that there is something of the eternal traveler who renounces the impositions of economic productivity to produce poetry?

When you learn new languages, you meet new people, you see the universality of community. If you speak their language, they’re flattered and happy. If you only talk about yourself, they’re not. You wander, you don’t plan what you’re going to do. Most Americans, when they see someone, they only want to talk about how great they are. But if you’re interested in others, it’s better for you. It’s natural. I’m interested in people.

And this is the key to writing great poetry?

It certainly is a help. It’s like being interested in rugs.

In your pocket anthology Modern European Poetry from 1966, you’re the one who exclusively translates Machado, of course, Jimenas, and Salinas. They’re very evocative and rural and beautiful, like landscapes. They reminded me of Japanese haikus. The quiet epiphanies and the simplicity—is that a commonality you look for?

I’ve always been interested in pictorial poems. The great poets of the 20th Century were Russian, Spanish, and Greek, and of course some wonderful French and Italian, too. And I think that’s largely it. There are all kinds of ways of speaking Spanish, but there’s nothing like Castilian. It’s so beautiful. I like Andelusian, like Lorca. He spoke marvelous Spanish. In Northwestern Spain, it’s almost Portuguese, a mixture. I wish I could have known Lorca but he was murdered in 1939. He was the greatest.

The two best poets of the 20th Century are Lorca and Dylan Thomas. When people asked Dylan Thomas, who was the greatest poet, he said Lorca. He didn’t know Spanish, but he knew him in translation. In 1951, I went to see his play in New York—Under Milkwood—and they wrote in the papers that he was all washed up, but he was only about thirty-seven. We saw him on stage, he looked like he was twenty-five with a magnificent voice, like nothing you’ve heard before. Now I don’t like all of Dylan Thomas. His last poems are just wonderful, his plays. His short stories are also fabulous. But most of his poems are not good. It doesn’t matter… So I’m coming back from the play, there’s snow on the ground in Central Park, and I have to go back to the West Side where I live and suddenly I’m walking along, and this guy bangs into me. It’s Dylan Thomas. We’re both rolling in the snow. And he says, “I’ve got to get back to the Chelsea Motel.” So he got roaring drunk when he went downtown, at the White Horse Tavern. And unfortunately that was that.

Did you ever hear of the poet Ruth Stone? She’s a good poet. She won a Pulitzer. She was one of our closest friends. And she was funny. She told me this story that she and Richard Wilbur were in the front seat, driving, and in the back seat was Dylan Thomas and Wilbur’s wife. And when they got where they were going, Wilbur’s wife said, “I didn’t know what to do. He was feeling me up all the time. And I didn’t even have a brassiere on.” And Wilbur said, “You should have been happy, you had more fun.” I’ve heard a lot of stories from the horse’s mouth.

Do you find poetry a form of play?

Poetry has to flow. If it doesn’t flow, it sinks. It’s like when you swim.

So Willis, we have one more question.

Only one!

When you approach translation, especially in poems that communicate some form of desire, is the desire yours, or are you trying to convey the desire in the poem, or is it a combination? For instance, when you write your own sonnets, your love is coming through. But when you’re translating, are you picking up, are you finding your own sensuality in the poem and transmitting that?

Well, for me, language is like pancakes. They pop up sometimes, or lie flat. I’ll tell you one thing: I’m very lucky that I haven’t lost my mind. So many people do. And Sarah, she gets worried by the hour, and I can’t get away with jack shit.

I have no idea what people do today. I like to paint every day, if I can. And I like to write every day. And I haven’t lost any enthusiasm. I’m still a hungry artist.