Judithe Hernández’s studio is on the second floor of the Arroyo Seco Bank Building, a landmarked Beaux Arts commercial two-story at the corner of North Figueroa and York in LA’s Highland Park neighborhood. Inside, the units are tucked away behind frosted glass doors, and with the sound of my footsteps echoing down the hall, I feel like I’m walking into a hard-boiled novel. But once invited into her studio, I’m treated to the industrial, clean lines of metal cabinets, desks, and canvases that meld with the colors of decorative items like Mexican masks, plates, and framed reproductions of Lotería cards. It is bright and airy, filled with reds, yellows, and whites.

Born and bred in Los Angeles, Hernández launched her art career as the lone female member of “Los Four,” the seminal artist collective that was instrumental in bringing attention to the Chicano Art movement of the 1970s through a striking array of paintings, murals, and sculptures. Her masterful pastels depict surreal scenes of the archetypal Mesoamerican female that are often haunting, often sensual, and always emotionally captivating. Her works display an elegance of line and composition that harkens back to masters ranging from Mexico’s famed “Big Three” to the Pre-Raphaelites.

Hernández is welcoming and unguarded. “Have you had the Mexican soda Penafiel?” I opt for a lemon-lime. We sit down on a red couch as she shuts the television off. She is an easy-going, gracious conversationalist, and Michelangelo, George Kubler, and the odd, choice expletive can blend seamlessly in conversation, making for an experience like chatting with your cool aunt who did all the things your parents didn’t but still made it to all the important family events.

After a conversation during which I learn details about her activism-filled ‘70s, her creative process, and uncover the mystery behind why, at the height of a continued upward trajectory between 1970 and 1983, she left it all for a 26-year stint in Chicago when she made no art, Hernández says, “It’s customary in any Latino household to have your guest part with a gift.” She hands me a small glassine bag. “This is for you.” This interview has been edited for style and clarity.

Judithe Hernández first won acclaim in the 1970s as a member of the celebrated Chicano artist collective Los Four. The collective would become a major force in the Chicano Art Movement and the first Chicano artists to break through the mainstream museum barrier, earning recognition as muralists during the renowned Los Angeles mural renaissance. She and fellow member Carlos Almaraz painted murals for labor rights leader Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers Union, as well as community murals, such as the Ramona Gardens Housing Projects in East Los Angeles.

Hernández’s inclusion in museum and gallery exhibitions in California began immediately following graduation from Otis Art Institute in 1974, with landmark exhibitions at the Oakland Museum, “In Search of Aztlán” and “The Aesthetics of Graffiti” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. By 1983 her career moved to the national level with a solo exhibition at the venerable Cayman Gallery in New York, making her the first Chicana to extend her artistic reach beyond the West coast. The international significance of her work came in 1989 with the first exhibition of Chicano art in Europe, Les Démon des Anges, where she was one of sixteen artists whose work was part of this ground-breaking exhibition.

Over her 50+ year career, she has established a significant record of exhibitions and acquisitions of her work by major public institutions and private collections which include: the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Philadelphia; the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago; the Smithsonian American Art Museum; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin; the UCI Museum/Institute for California Art; the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture; and the AltaMed Collection. She has been the recipient of the prestigious Artist-in-Residence at the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, & Culture, University of Chicago; the City of Los Angeles Artist Fellowship (C.O.L.A.) and the Anonymous Was a Women Grant. In 2019, after more than 40 years, her artistic presence returned to downtown Los Angeles with a seven-story mural, “La Nueva Reina de Los Angeles,” at La Plaza Village one block north of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument District. In 2024, she became the first artist to be given a major retrospective exhibition at the new Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture.

DM: You refer to yourself as a drawer, first and foremost, not a painter.

JH: That’s right, that’s why I use pastel. I can paint, but I don’t really enjoy it as much. Although I enjoy murals. I think everything has to do with the way I was trained at Otis. The curriculum centered around the five different MFA programs—one, fine arts (painting & drawing), two, design, three, ceramics, four, sculpture, five, printmaking. Once you’ve been trained the right way, you should be able to do anything in the art world. Drawing is my favorite medium because, like many people who have art in their system, it’s the first way human beings express themselves. Thanks to my training at Otis, when I needed a “day job” I was able to work as a graphic designer. I designed books, fonts, all kinds of things to support making art.

You went to Otis College of Art & Design in the early 1970s, back when it was in MacArthur Park in the middle of the city. What was it like studying under Charles White—his pedagogical approach, his influence on your style and that of your peers?

I met Charlie before I was at Otis. My high school art teacher was a white woman, Eleanor Downey, the first major influential person in my life who was not in my family or related to me in any way. After I took her class in the 10th grade she arranged for me to always be in her advanced class. She cleaned out the storage room next to her classroom and said, You’ll be working in here because you don’t need to be doing what they’re doing. That was huge—to be a teenager and to have your own studio, you know? Mrs. Downey was a good friend of the artist Joseph Mugnaini—he illustrated all of Ray Bradbury’s books—who was a professor at Otis. He taught an extension class on Saturdays, mostly upper-class housewives. He invited me to sit in and use the live model. He said, “You don’t have to pay, just sit in the back of class.” I, of course, said I’ll be there, and on the first or second Saturday Charles White was there.

During my first year at Otis—I was always a nerdy student, always trying to work to the expectations of the instructors if not my own— Charlie gave us a drawing assignment to do over the weekend: “I want a three figure composition, and I want it on the wall Monday morning so we can critique it.” I went home and spent the entire weekend doing this rather large drawing. Took it to class, put it up. When Charlie arrived he walked around silently, around and around and then stood in the middle of the room and exploded. He started swearing—“You sons of bitches this is the shit that you give me! You had the whole fucking weekend…” We sat there in our chairs and just sank. And when he finally stopped, and took a breath, he said, “The only person this does not apply to is Hernández!”

I also think one reason that we got along so well was his first wife Elizabeth Catlett, an African American printmaker from the forties, took him to Mexico and he absolutely adored it. One day after class, he told me, “My wife had this internship at a print atelier in Mexico City, and I got to go along. I met all these artists, and talking to them, working with them, being there with them was the first time in my life that people who were not Black treated me with respect and admiration for my work and for me as a human being.” He’s a giant of 20th century art. Social art, political art. Very few people understood how important he was back then but I think they do now.

What were the influences in class? Was it a focused curriculum or a sort of free expression to find your style like at Chouinard?

Oh no, Otis in those days was not like Otis today. It was a much smaller school. By and large the professors were predominantly men. Many were the children of European immigrants or recent arrivals who came after the Second World War. Most had been brilliantly educated as artists in Europe. We had these really incredible artists—all very accomplished and all trained in the classical Renaissance manner. On the first day we walked into painting class, Joe Mugnaini said, “You are here to learn how to make art. You will not be making masterpieces, divest yourself of that notion, that is not what you’re here to do.” They trained us from the bottom up. If you’re going to make sculpture, you’re going to build an armature and learn to make plaster, if you draw you’re going to learn how to make paper. They gave us such an incredible education. The point was, great art is the product of intelligence, imagination, and skill. In my opinion, so much art you see today is produced by artists who lack the skills to translate what they see in their heads. Many of the ideas are wonderful, but the less than stellar execution weakens the aesthetic and visual impact of work that would otherwise be outstanding.

How did politics enter your world, the desire to align your art with a political movement? Was it something you got out of Otis, or were you already interested on your own?

My mother was a rabid Democrat. If my brother and I wanted to be Republicans she would have disowned us. She became involved in politics when she started college because she had a very progressive father. Wherever there was some kind of Democrat political thing going on, she was involved, she went to meetings, I think for a while our house was one of those places you could vote. When I was 12, we had been talking about socialism in history class, and I was looking in the paper and I noticed for a quarter you could get a subscription to the Daily Worker. I thought, Okay, I have a quarter. I put it in an envelope, filled out the form and sent it away and suddenly the Daily Worker starts coming to the house. And my mother started freaking out, saying, “This is a Communist newspaper!” And my father—who was a union man, he worked for the Southern Pacific railroad, down at the wheelhouse on Mission Road—said, “No, no, this is union stuff, it’s not communist, it’s good things.” And she’s like “they’re gonna think she’s a communist!” And he’d say, “She’s only twelve!” That’s how far back the political stuff goes.

The point was, great art is the product of intelligence, imagination, and skill. In my opinion, so much art you see today is produced by artists who lack the skills to translate what they see in their heads.

Were your parents from California? Or did they emigrate?

My mother was born in Mexico, in Zacatecas. Both of her parents were a blend of Spanish and Indigenous peoples, which compose most of the middle and upper middle-class of Mexican society. My father, on his mother’s side, came from one of those unique families in southern Arizona who lived in the same geographic location that has alternately been pre-Columbian Anahuac, New Spain, Mexico, and finally the US. My paternal grandfather was from Guadalajara.

Were there any members of your household interested in the arts or sciences?

There was an aesthetic element. The average Mexican person, or the average Indigenous person in this hemisphere—whether descended from the Aztecs or the Maya—they all have altars in their home, the dishes that are only used for decoration, and the masks on the walls. You can go into any household in East LA and you will find these colorful artifacts that are meaningful in terms of what they represent culturally. The aesthetic dimension is everywhere. In Mexico you see color everywhere, it’s in the blood.

How did you get the commission with Aztlán, the first Chicano studies journal? That was one of your earliest achievements, right?

That was in 1970. I was still at Otis. I graduated high school in 1966. In ‘67 I went to East LA College, because in those days Otis required two years of general-education. I’d gone to Otis in ‘69, then I was thrown out because by that time I was getting involved in the Chicano Movement and I hated the guy that was teaching the ceramics class and I didn’t go and I failed it. When they threw me out for a year my parents were mortified. But I got a lot done that year. I became involved with a UCLA group that was part of the first Chicano Studies department, the brainchild of Juan Gómez Quiñones, a brilliant Chicano historian who was a young professor then. I was dating a guy who was in law school there, a Chicano student, who said, “Why don’t you come to this meeting with me? We’re gonna start a journal, and it might be interesting.” Juan came up to me and said, “Andrew says you’re an artist.” I said, “I’m studying to be one.” “Well we’re starting a journal and we’re going to need somebody”—he thought art was important, especially when you marry it with the written word—“I want an artist to illustrate the cover and do drawings inside.” “I can do that.” “Okay, you’re hired.” Sight unseen.

How many issues of Aztlán did you work on?

I did five years-worth of their journals. That’s about twelve covers. There were two per year, a spring and a fall issue, and some special issues. I forget how many journals I worked on specifically, but it was a hundred and some-odd illustrations.

So that’s 1970. You met Carlos Almaraz, the Mexican-American painter and key member of the Chicano art movement, at Otis, correct? Tell me a bit about that relationship.

Carlos Almaraz was one of my closest friends. We met in 1972 when we started grad school at Otis. We found we had the same sort of thoughts about so many things—artistically, politically. We wanted to be a part of the Movement because we were tired of the racism and discrimination. However, we both also had that crazy little dream—two kids from East LA who were not expected to dream about careers in fine arts—to think we could, with our college educations, make it all the way in the art world.

Carlos was probably the most talented artist the Movement ever produced. When he was very young he left home with another friend from high school, Danny Guerrero—the son of Lalo Guerrero, the famous entertainer—who was also gay, and went to New York. It nearly killed him. This was the mid-to-late 1960s. He was trying to be a minimalist painter, and although I really like his work from this period, something wasn’t working, it wasn’t enough for New York. He was drinking, he was doing drugs, he was close to killing himself. When he came home from New York he felt disconnected from the Chicano movement. He left before it really got going. Suddenly he had this Come-to-Jesus moment, “I gotta catch up and find my identity!” Sure enough he leaped into finding what it means to be Mexican—learning Spanish, working for Cesar Chavez. Carlos’s charm was such that he would go right over to the most important person in the room and introduce himself. People found him incredibly charming which enabled him to make important connections, becoming a face everyone knew. He became involved in everything, never said no to things, did his homework, and began to form opinions that were not only in agreement with the Movement but more imaginative and progressive. He was the force behind Los Four’s recognition and his paintings became extraordinary. Unfortunately Carlos died five years after I moved to Chicago, from complications of AIDS.

How did you become a member of Los Four? Were you already an informal part through Almaraz, and after the LACMA show you wanted formal admittance? Or was it the show?

Carlos and Frank Romero had gone to Garfield High School. They were friends. And then through Frank he met the other two, Gilbert Luján and Beto de la Rocha. They had a show at the gallery at UC Irvine they named “Los Four” because there were four of them. I think that was in ‘72—a couple years before LACMA. Hal Glicksman, who’d seen the Irvine show, told the people at LACMA about the exhibition and suggested they bring it to LACMA. By that time Carlos and I had become friends and he understood that they needed a woman if they were going to have some legitimate claim to being progressive artists, to being inclusive irrespective of gender. ASCO had a woman member, my friend Patssi Valdez was a founding member of the group and they were younger. It made these OG guys look pretty feeble. They were talking the talk—about being radicals and socialists—but they weren’t allowing in any women! So Carlos kept telling them, we should add Hernández. So I brought my portfolio over one day in ‘73, between the two shows, and they said, “She’s good, she paints like a man.”

By that time it was very close to LACMA, and because I had not been in the original [UC Irvine] show—they were only displaying the original members—my work would not be included. However, every show after that I was a formal member. In fact, right after the LACMA show, “Los Four” went to the Oakland Museum in ‘74. And immediately—the Chicano artists who had never had a museum show had become the first to break through the museum barrier—with exhibitions at the Crocker, the San Francisco MoMA, all of those happened within 18 months of one another.

I liked these guys as human beings. I mean they were a little misogynistic, but I understood the type. I grew up with guys like these. Carlos was different, probably because he was bisexual. He was the one who had that kind of sensitivity about trying to balance things, and he’s the reason I became a member. After about a year after those shows ended, Beto and Luján were no longer active. Beto had emotional problems and Luján was married with kids, got a job…

What’s the scene like in LA during this period, what’s the day-to-day, who are you associating with?

We went to a million meetings—Marxist, Leninist meetings. I have my own copy of Mao’s Little Red Book that Carlos gave me because he wanted me to read the part about what Mao said about art—that all art should reflect the life of the working class and consider them an audience.

You’ve said that the Chicano Art Movement was “the first huge body of American art that was produced in response to a socio- political situation, not the other way around,” and that you and the other members of Los Four were “soldiers in a battle.” How did you come to see art as instrumental to the goals of El Movimiento?

You know who made us feel it was important? Cesar Chavez. Carlos and I would go up to the United Farm Workers headquarters in La Paz, which is up in the mountains above Bakersfield, an old TB hospital the state gave them. We would paint the banners for the big conferences. Cesar thought artists and journalists were very important to any political movement. He said every great social movement, every revolutionary movement always relied on visual symbols with which people could relate, as Mao did. Revolutionary imagery like the hammer and sickle of the Russian revolution, the posters for the Cuban revolution, the Polish [Solidarity] movement in the 1980s—you don’t need to tell anyone what those graphics mean. They’re direct and speak to the working class. Carlos also spent time working with the UFW journal that the farmworkers produced. We’d also go up there and paint Huelga murals and design posters.

Did any of the individual aspirations of being a great artist clash with the collectivist goal of the Marxist revolution? What was the environment between the groups like?

That’s a personal challenge. I have always thought art is too important to do badly. It’s like writing, you can’t have the impact you think you’re going to have if the execution isn’t great. That’s what you hope for. There is a reason that Michelangelo’s work has stood the test of time. Not only does it have incredible beauty, done in a way that is so exquisite it’s hard for others to believe such a work is man-made. The Pietà for instance, it’s not just a great religious sculpture of Mary holding her son, but if you’re a human being—or a visitor from Mars—you can look at amazing works like this and feel its emotional impact no matter who you are or what you believe. That takes remarkable skill, as well as a subconscious response as they stand in front of an easel and let it flow. “If I was made for art, from childhood given / a prey for burning beauty to devour, / I blame the mistress I was born to serve.”

Dreams Between the Earth and the Sky, 2018

Were there any times your personal or artistic decisions—say in terms of furthering your career—would clash with, say, “the cause”?

When I think back on it now, I see how different my career would have been, how different my world would have been had the Chicano Movement not happened around me. I would have left Otis with a set of skills, like my white counterparts, and gone out in search of something interesting to paint. I might have become an okay painter with an okay career. I used to think I had been born in the wrong time but now, 76 years later, goddamn—I hit it just right. The Movimiento gave my work purpose.

And yet, your artworks have a very surrealist, even symbolist, quality, which is a far cry from socialist realism. Were you drawn to European artists in that vein in school, or had you already been interested in representing the innerworld, so-to-speak, from a young age?

I thank my mother. There wasn’t a lot of money in the house but every time we went to the market—markets used to sell series of books for like a dollar, new ones every month—they would have, say, “The Great Painters of Europe,” so Picasso, Raphael, Michelangelo—

—at the grocery store?—

—at the grocery store! One volume a month and my mother bought all of those. When there was something else, like history books, “History of the Roman Empire,” she bought all those too. Probably not too many people in East LA had what I had in terms of books. My mother was an incredible reader, she also introduced me to Shakespeare.

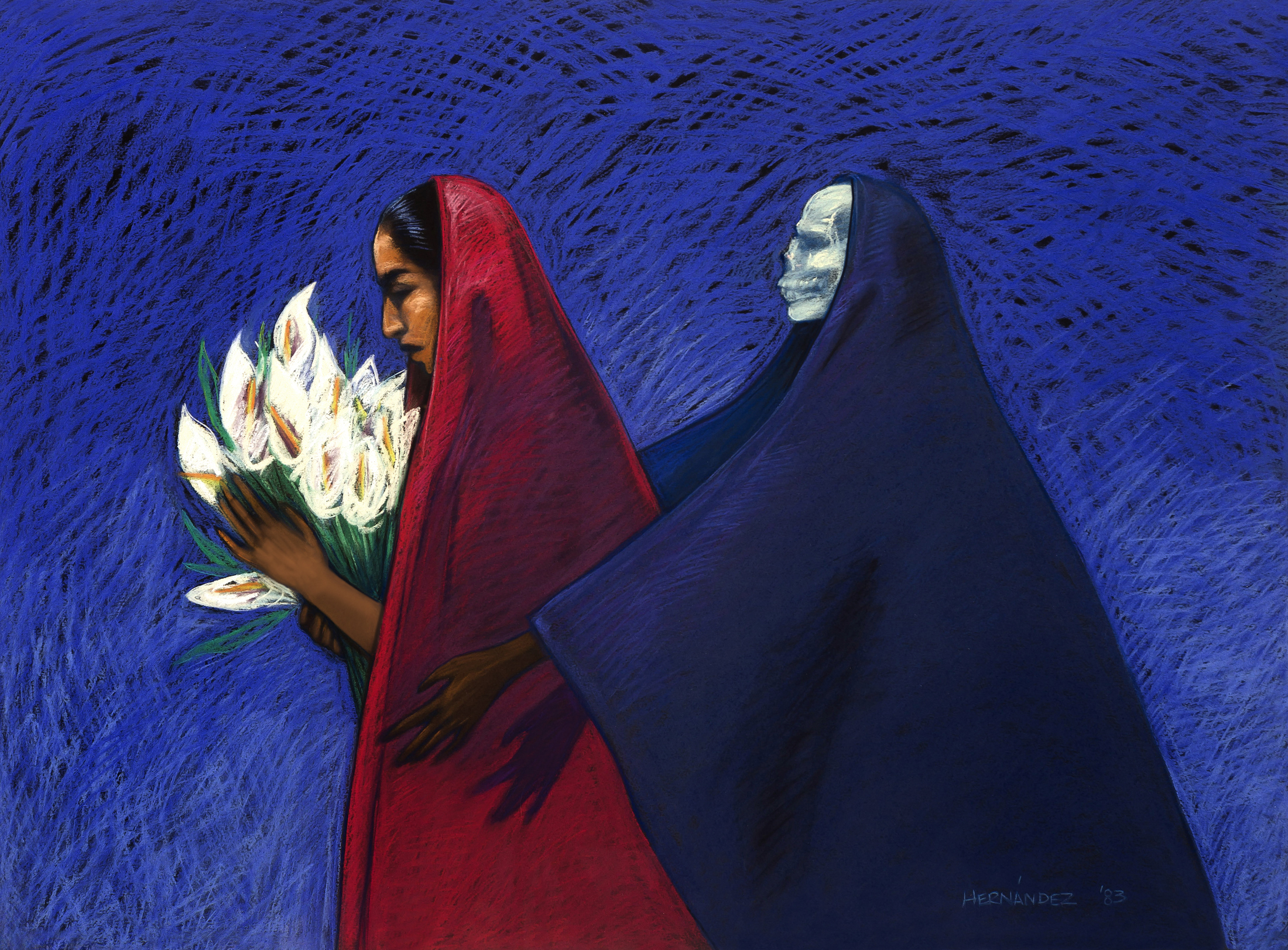

Flores blancas, 1983

Unconquered, 2021

But I will say this, in my humble opinion, it is the great indigenous cultures of the world who continue to preserve the willingness to see ordinary things through a magical lens. Maybe there’s something about the indigenous mind that maintains a belief in the supernatural. And maybe it isn’t real, but if you believe as a society that spirits can return, like in Día de los muertos, then a magical dimension of the human imagination lives on. Human creativity resides in that dimension. Children have the capacity to think in magical terms which fades as they grow—unless they’re artists! Have you read George Kubler? I read The Shape of Time probably two years after it was published—in the mid ‘60s. That first chapter— the whole thing about actualité—is so riveting for an artist, and it has obsessed me since I was a kid: “Actuality is when the lighthouse is dark between flashes… the instant between the ticks of the watch… the rupture between past and future… it is the void between events.”

Christopher Knight, the Los Angeles Times art critic, suggests yours is “a world where logic does not reign, independence is essential and the unconscious is a mechanism for self-knowledge.”

Well, that’s what all artists do—or at least all the good ones. I don’t think it’s anything special. I’ve always been one of those people who don’t like to overthink what I’m doing. With pastel you have to have a plan, it’s a very unforgiving medium. You can’t make a mistake, at least not a serious one, without tearing it up and starting again. There’s no painting it white. So I always have a plan. I’m 76 years old but I know how to use Photoshop. That has certainly made putting together a basic “map” much easier. When you take that small image that you’ve done in a sketchbook and enlarge it, or transfer an image to a mural-sized grid, it changes. What looked great small sometimes doesn’t work when it’s bigger. For an artist, it’s like playing chess, forcing you to find a better strategy. As a storyteller I know where I’m going with an idea. Once I start to work I let my creative dimension guide my visual decisions as the work progresses. I have cataloged images in my head since I was a kid. I wake up most mornings with something I will put on paper someday.

But you don’t consciously think about—

—Not really. Not unless it’s a historical thing, but I don’t do a lot of that. And I don’t do portraits either.

From the Aztecs, the Mayans, the Spanish, to contemporary Mexico. Women have always paid a high price.

Specifically with the more challenging pieces, like the “Adam & Eve” series or the “Juarez” series, is it difficult to maintain the mood throughout composition? Do you live with these worlds in your head?

No—I don’t know about other people but—it’s just like going to work, you know? You know very well what you’re talking about—that happens first. I build the image in my head, then for me, the fun part is the mechanical challenge of bringing that image to life. But when I’m sitting in front of the easel, it’s hard to explain. Nothing bothers me, physically, mentally.

How long do pieces like the “Adam & Eve” series normally take?

The “Adam & Eve” series rolled out pretty fast. Some of the other ones have taken years. Because pastel is so unforgiving, I work on something until I reach a point where if I don’t want to ruin it—if I’ve got a good start but I’m not sure what I want to do—I put it away. There are some pieces that were in drawers for 20 years, sometimes longer. And I was right to wait, because when I finally did know, all of it became mechanical—it’s not emotional or anything like that because the plan didn’t change. It’s the way I chose to execute the plan. On my computer I’m thinking ahead to the next two or three years. I have these files and I’ve probably six or seven ideas and I choose which one to build out on paper.

Only eleven pieces from the 20th century made it into “Beyond Myself, Somewhere, I Wait for My Arrival,” your retrospective at the Cheech, and nine of those are from 1982-83. Could you talk about the gaps in time, say, the works from your political period in the 1970s?

Well a lot of the early work doesn’t exist. It was lost in time. A lot of the paper pieces just disappeared. Between moving, and people stealing my work actually… It happened a lot in school, I finally had to stop pinning my stuff up overnight or it wouldn’t be there the next morning. I guess that’s very flattering. So there just wasn’t that much from that period. I think María Esther Fernández [Artistic Director at The Cheech Museum and curator of the retrospective] did a great job. Hopefully it will look that good in El Paso.

Juarez ciudad de la muerte, 2008

En mis sueños soy una novia, 2019

That’s where it’s going next?

Yes. And that’ll be the last place. Pastels are very finicky. Every time you move it something falls off. Two is enough, and being in El Paso is important because of its proximity to Juarez. I’m hoping that brings attention to the largest body of work there—the “Juarez” series.

Those pieces, along with the “Luchadora” series are laden with symbols—thorns, antlers, snakes, masks, sewn faces—I wanted to know specifically about the sewn faces, what do they signify for you?

It depends on the piece. But the “Juarez” series is a reminder that young women are easy targets at the factories where they work, much like the women sacrificed by the ancient cultures of Mesoamerica. The mask represents the continuum of the brutalization of women, that women are expendable—from the Aztecs, the Mayans, the Spanish, to contemporary Mexico. Women have always paid a high price.

Yet, back to those artworks from 1982-83, they are extraordinary—somber and ghostly— and I can only imagine what would have happened had you continued. Momentum seems so important—you’d had a solo show at the Cayman Gallery in New York—tell me about this decision to abandon it all and to go to Chicago? You just turned away?

Part of it is cultural. I was in my late 20s, early 30s by then, and in my world I was getting old, fast, and I wasn’t married. Even though I wasn’t looking for that kind of relationship, my mother would occasionally get after me. I had been in a relationship that I thought was leading to marriage but we had a serious falling out. And that’s how I ran into Ariel’s father, on a blind date. He was a very nice guy, a nice Jewish boy, nice family. So we decided to get married.

Did you know you were going to have to make any artistic compromises?

At that point, no. His father was an architect and he was trained as an architect, but he never practiced architecture—he was a great architectural photographer, but he didn’t pursue that either. We lived in a loft in downtown LA, I was making art, and he thought—for himself—that he would do better in Chicago. He had a dream of returning home again—although he hadn’t lived there since he was a child—and I thought, maybe a different audience would be good for me. I was dumb enough not to have done some research. I didn’t understand how the art world worked, especially not in Chicago. I couldn’t even get hired at the School of the Art Institute. Here in LA I was getting shows, I was in museums, but in Chicago, nada. In life we often make some dumb decisions based on what your partner wants instead of what you want. Women are asked to do that all the time.

Did you feel while you were working on those paintings that you were on some kind of a breakthrough?

Not exactly. At that point I was working on a trajectory to find an archetypal female protagonist. And if you look at the art of other Chicana artists of the time, their female figures looked very indigenous. I was looking for something more universal. When I look back at my early sketchbooks in high school, I was already doing that, trying to find the face, a beautiful face.

And then you return. Most of the pieces in your retrospective are post-2010, with a majority from the period between 2008 and 2015. How did you get back into creating art?

We lived in Chicago until 2010 and over the years I developed a good friendship with Carlos Tortolero, president of the National Museum of Mexican Art, who knew my reputation out here. I felt like a fish out of water for a long time until I met him. He would constantly invite me to different exhibitions that would open. And I would ignore them because I wasn’t making any art. I had no studio. Around 2004, he contacted me again. A Frida Kahlo exhibition opened at the museum. My daughter and I went to see it and I left him my business card—I was working for University of Illinois, Chicago—and by the time I got home the phone was ringing! He told his curator, “You know where artists work—find her a studio!” So, in 2005, I gave myself five years to get my bearings back as an artist. This was a chance I couldn’t ignore. In 2009, Carlos surprised me again. “We know you’re leaving, and so we’ve decided we’re going to give you a solo show.” And I said when? “2010.” In the same space the Frida Kahlo show had been in. This was my farewell to Chicago and my rebirth in LA. I’ve made up for a lot of lost time. But you know, even when I wasn’t making art in Chicago, I thought about it everyday, saving images in my head.

La reina nueva, mural, 2019.

How do you feel about LA today?

It’s getting better. Except LACMA—I don’t know what’s going on there. Why would a museum spend a shit-load of money to make it smaller? I question whether you’ll see artists of color there much. Fortunately, Chicanos have a growing professional class who have deep pockets and who support the arts. That’s what we lacked for a long time. Since the Cheech opened, two other Chicano/Latino museums are rumored to be in the works. After a five-decade career, I find myself represented by a Westside gallery and selling work. Good things come to those who wait.