Author’s Note: To commemorate the release of Dispatches’ sixth issue, “Beyond Media,” this edition of Headventures will consist of the “Story of My Typewriter,” which recounts my journey from a broke 23-year old with laptop fatigue to a bona-fide typewriter nut in the space of about a dozen years. Originally written as a contribution to the Beyond Media Symposium.

[drop-cap]

I could have started out with an Olympia, or a Smith-Corona. Instead, it was a 1953 Remington Quiet-Riter. For over a year I’d been lugging around a brick of an old MacBook my ex-roommate gave me which only worked while attached precariously to the charger by magnet. By the time I’d had enough, I started to believe only physical pages of manuscript meant anything, not these digital “files” I habitually rearranged in pixelated “folders.” We didn’t have typewriters in my house growing up—encouraged by my father’s business partner, my parents were early practitioners of the personal computer. If a typewriter came on screen in some film, it carried no special significance for me. Yet, one day in the summer of 2014, I began searching East Bay Craigslist for one.

I took the bus out to Fremont, where I’d never been, to buy this large, rather imposing-looking machine, of which I knew nothing about, for a reasonable $35. It was bulbous, crinkle gray, with forest green plastic keys. It reminded me enough of an early ’50s Chevy Bel-Air to consider its stylings “classic.” The Remington had belonged to a friendly man who recalled last using it to write a high school term paper in the 1980s, after which it sat languishing for decades in an attic likely surrounded by other exiled signifiers of the suburban American dream. All the while I rode the bus back to Berkeley, I clutched the brown suitcase-like carrier closely, my mind filled with romantic images of Kerouacian rapid-fire, pages amassing, acclaim following. I still remember that first odorous burst when I opened the case back on Ridge Road: a mechanical musk that smelled long-dormant and pregnant with possibility; I admit, I embraced it for a moment. I didn’t realize it right then, my enthusiasm mistaken for a mere mixture of ambition and gerontophilia, but I’d been infected with typewriter fever.

“Remi,” as I affectionately called it, was big, heavy, and got work done. I never realized writing could be so rewarding—the sounds it emitted its own strange tribute to the kinetics of Art—and so difficult. So many pages filled with errors and nothing you wanted to read, because suddenly nothing you read now, rendered on timeless Courier-like type held in your hands, ever sounded quite like it did in your head. During my MagnetBook year in Boulder, I’d fed endless screeds into the infinite white, taking my satisfaction from words-per-hour records I tried to smash. Little of what I wrote seemed more than typing. Thus, faced with this new challenge that both repelled and beckoned to me, I remained relatively reserved those early days in Berkeley. The concept of starting a collection didn’t even occur to me until I made friends with the staff at the (now defunct) California Typewriter on San Pablo Avenue.

Through a combination of their encouragement and the careful eye of generous friends, my collection eventually grew to four machines. Then I gave one away, moved to New Orleans, and quickly acquired two more. I took the brown Smith-Corona Sterling I saw going for $50 in the entryway of a junkshop in the Bywater on my second full day in town as a sacred sign the city was welcoming me and my Faulknerian designs. I dripped sweat into my machines, got whipped by windswept storm drops while writing on my machines, and chased pages around my second-floor studio in Mid-City when summer storms blew gales through my ever-open windows—pages the amassing of which no longer spelled romance but burdensome problems I strained to solve. In cash-strapped preparation for my move back to California, I sold two more—including “Remi,” a sale I occasionally regret. In Los Angeles, I traded “Erika” for an Olivetti Lettera 32.

He nudged me, perhaps out of professional intuition, toward the Lettera. Instantly, I was invigorated by the snappiness of the action, by a sort of “athleticism” I’d never before experienced. It was like swapping a lived-in 302 Ford Mustang (my Royal Arrow) for an Alfa Romeo Spider Veloce.

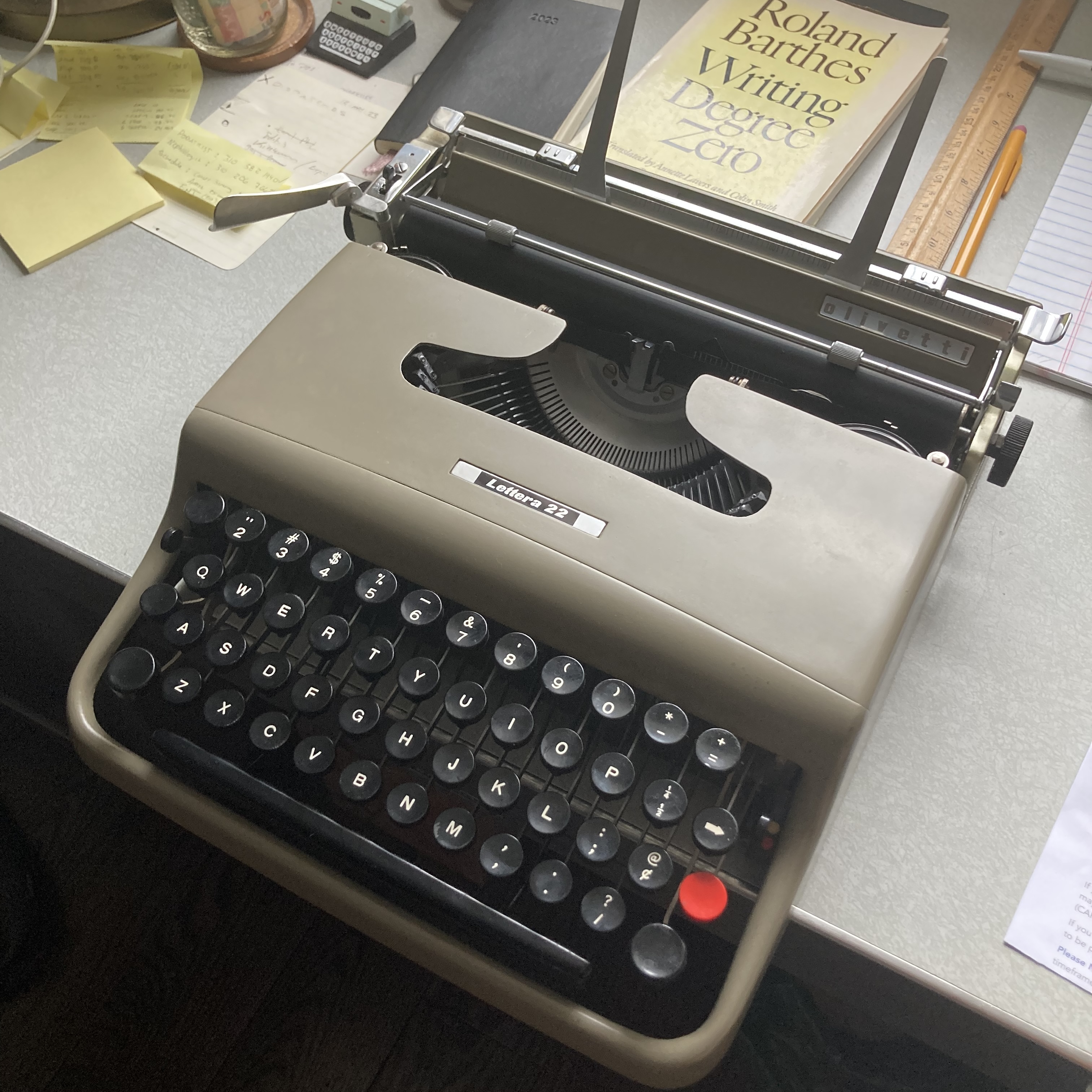

Will Self, a fellow typewriter aficionado, has called working on an Olivetti “indecently pleasurable.” It’s difficult to put into words just what I feel while working on one that is unlike other machines I’ve used (though Royals are a near second), but Self comes closest. It is easy, however, to say that during Olivetti’s peak—the 1950s and ’60s—no other machines better embodied the mid-century modern promise of enlightened design and uncompromised engineering. Perhaps the Swiss-made Hermes were a notch above in terms of pure luxury; the German Olympias a notch above in terms of brute technical excellence. But the place occupied by Olivetti through the strength of its Lettera 22, Studio 44, and Lettera 32 (all three of which I now possess) is forever sanctified by the work of its adherents—Raymond Chandler and Tennessee Williams (Studio 44), Sylvia Plath and Clarice Lispector (Lettera 22), John Cheever and Martin Amis (Lettera 32), among many other luminaries.

My 32 came from Rees Electronics in Westwood, a shop on the second floor of a nondescript, two-story office building run by an affable, burly, wispy-haired German named Helmut Schulze. Schulze is surrounded not only by typewriters but by clippings and printouts and signed portraits of their collectors, devotees, and acolytes. His excitement, barely concealed by Germanic stoicism, betrays a deep fondness for these intricate machines and the relationship they share with their practitioners. Though he touted the virtues of Olympias without fail, he nudged me, perhaps out of professional intuition, toward the Lettera. Instantly, I was invigorated by the snappiness of the action, by a sort of “athleticism” I’d never before experienced. It was like swapping a lived-in 302 Ford Mustang (my Royal Arrow) for an Alfa Romeo Spider Veloce.

For the first few weeks I couldn’t stop staring at it. I struggled to believe the machine I had was identical to the ones in the photographs of so many literary heavyweights. Still, little of any value rolled off the platen. I found myself going back to the old Royal for succor, as though my model’s lack of any clear forebears eased the pressure: we were both complete unknowns, Arrow and I.

Soon enough, however, I fell under the spell of compulsively searching online for the 32’s older brother, the Lettera 22. Designed by Marcello Nizzoli and released in 1950, the Lettera 22 was just that little bit shorter, rounder, and unabashedly elegant in a way the 1960s Lettera 32 was more practical, rugged, and boxy. The 32’s action resembled staccato, rapid-fire weaponry, and I’ll admit to getting my keys jammed up more often than I had in years. I began, simply, to pine, as one does, for a Lettera 22. It became something of a holy grail typewriter for me (every collector has one), the one I believed would be the distillation of all I’d learned in my years of typewriting and would put to rest the relentless searching that began about six months after I acquired “Remi.” (The search never ends.)

We were driving down Washington Blvd in Culver City when I pulled over in front of an overgrown gate next to a small lot packed with mid-century modern furniture. My mother had just died and my fiancée, my brother, and I were driving around town in a foggy haze trying to get things done. They looked at me quizzically when I shut the motor off and told them I had to pick something up. I entered the small showroom of Vintage Visions and headed straight for the proprietor. He grabbed the brown leather and tan khaki carrying case for me and unzipped it delicately (if there’s one fault with Olivetti Letteras it is their stylish, zippered soft cases, which have not weathered the decades well). There, resting in camel-colored flannel lining and accompanied by the original manual and Olivetti warranty mailer, was a taupe Lettera 22. After a cursory inspection and sampling of the round, trampoline-like keys, I Zelled the man $125—a steal.

Home that evening, I found the feeling I was looking for—an ineffable combination of soft, inviting pliancy and rapid precision. Understated and sophisticated, it even smelled more refined than my American machines, models that emanated memories of my long-gone step-grandfather’s garage, filled with tools and lubricants and an old Buick Riviera. The 22 was the convergence I was looking for—of design, action, pedigree, even of 20th century history in a strange way, although that’s another story. The last thing I did that night was slide the carriage over to the left, copy down the serial number, and search the Typewriter Database for Lettera 22 production dates. I spotted my machine’s number range, moved over to the year column, and there it was: 1956—the year my mother was born.