Author's Note: "Somebody must keep score," as Gore Vidal was known to say, and he could think of nobody better than himself to do it. In his absence this column will periodically report on the state of the post-culture and the temperature of the public discourse.

[drop-cap]

For most of a century, ever since his revival in the 1940s, the ritualistic flourishing of a quotation from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America has been a hallmark of the more intellectually aspiring American political journalism.* Introducing the translation by Gerald E. Bevan in 2003, Isaac Kramnick maintained, “If the number of times an individual is cited by politicians, journalists, and scholars is a measure of their influence, Alexis de Tocqueville—not Jefferson, Madison, or Lincoln—is America’s public philosopher.” No one has forgotten him in 2025.

Garry Wills, writing in the The New York Review of Books in 2004, was the rare naysayer, asking, “Did Tocqueville ‘Get’ America Wrong?” His answer: “Some people are astonished that a twenty-six-year-old Frenchman with imperfect English could write the best book on America, after a brief visit to the country. I am astonished that anyone can think he did.” Tocqueville was youthfully impressionable; and the travels with his friend Gustave Beaumont, were “erratic,” constrained by the necessity to spend much of their time visiting penal institutions, whose study was the ostensible reason for their journey. The vagabond aristo had little interest in the humdrum average American (“the most enlightened are the best company”), and his approach to democracy and America was the opposite of down-to-earth.

“Tocqueville is uninterested in the material bases of American life,” Wills charges. “It is as if he ghosted his way directly into the American spirit, bypassing the body of the nation.” I doubt that Garry Wills ever believed there was an “American spirit” to penetrate, as opposed to the material world of “American capitalism, manufactures, banking, or technology,” which Tocqueville neglected to explore. That said, there is something ghostly about his oracular point of view, something uncanny about what his doughty English counterpart, Lord Bryce, called his intuitions. Democracy in America is at times a strange, haunted book, but then, the United States in the Age of Jackson was in many ways a strange, haunted place, a twilight zone which Tocqueville reconnoitered in advance of its native sons Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville.

In the political realm the paranoid style, as Richard Hofstadter would later call it, was rampant. Freemasonry was a bugaboo for left and right (a distinction dating to the French Revolution). The anti-Mason movement, which had conservative New England origins in the 1790s, took on a populist, agrarian cast in the 1820s and ’30s; actual Masons, who tended to be upper-class, condescended to support the lower-class nativist anti-Catholic movement. Elaborate conspiracy theories exposed the machinations of enemies within, or bad actors recently arrived from abroad. (The Jesuits, for example, according to the more imaginative theorists, had infiltrated Freemasonry, which, in the form of the Bavarian Illuminati, had engineered the French Revolution.) Hofstadter: “All of these movements had an interest for minds obsessed with secrecy and concerned with an all-or-nothing world struggle over ultimate values. The ecumenism of hatred is a great breaker-down of precise intellectual discriminations.”

Paranoia struck deep in Andrew Jackson’s epic battle with the Bank of the United States and its head, the Philadelphia patrician, Nicholas Biddle. The Bank was the seventh president’s white whale and deep state. “‘The bank,’ said Jackson to Van Buren, ‘is trying to kill me, but I will kill it.’” The parallels to the present landscape of American politics needn’t be belabored, although it is irresistible to note that Jackson is one of his few predecessors that the 45th and 47th president professes to admire.

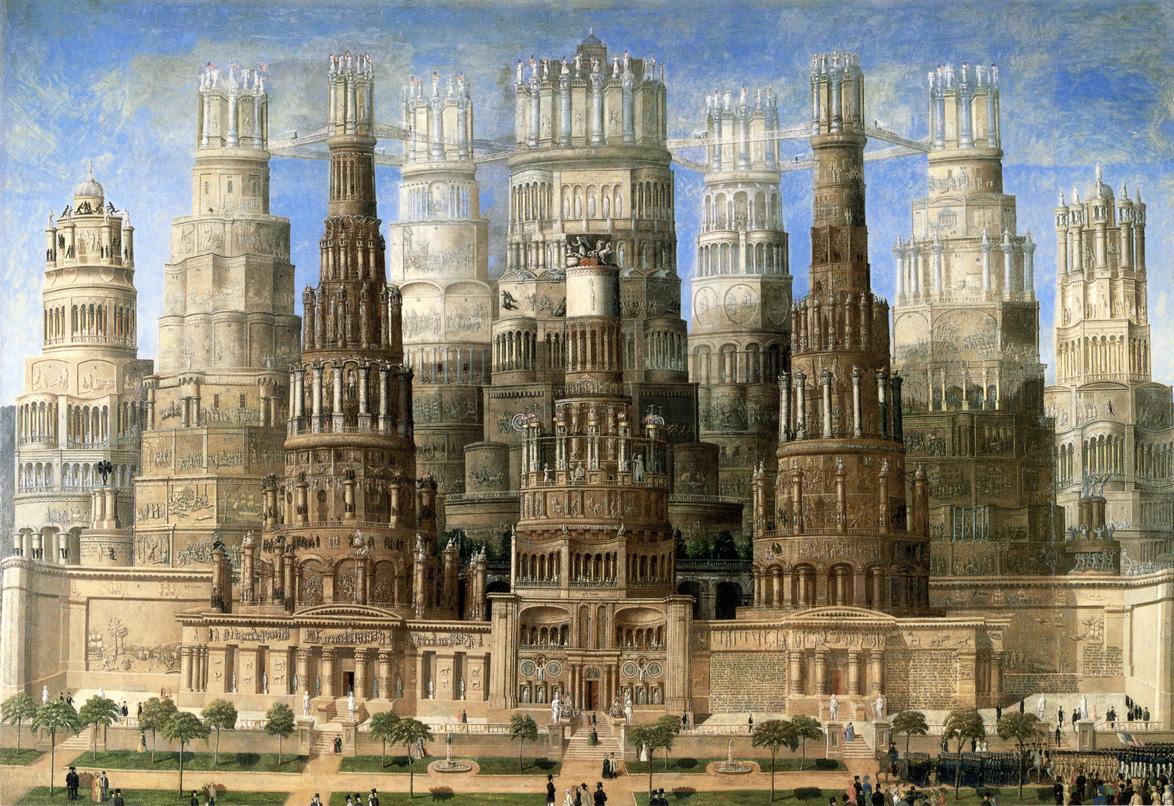

The paranoid style consorted, in a Pynchonesque way, with various crazes—the novels of Sir Walter Scott (for which Mark Twain blamed the Civil War) and Charles Dickens, temperance, supernaturalism, moralistic soft-core pornography—and, in the material realm, a fascination with ancient Egypt and its architecture which had crossed the Atlantic after Napoleon’s campaign in the Middle East in 1798-99. Raw towns on the frontier were named after Memphis and Luxor; sphinxes, obelisks, lotus pillars, and pyramids exoticized the American landscape, most conspicuously in the Washington Monument whose construction began in 1848. The Manhattan House of Detention for Men in Lower Manhattan, familiarly known as the Tombs, was, per the Encyclopedia of New York, “inspired by a photograph of an Egyptian tomb that appeared in a book on the Middle East written by John L. Stephens in 1837.” Masonry was widely believed by both its adherents and its detractors to have originated in ancient Egypt, and both Washington and Jackson were known to be Masons.

That said, there is something ghostly about his oracular point of view, something uncanny about what his doughty English counterpart, Lord Bryce, called his intuitions. Democracy in America is at times a strange, haunted book, but then, the United States in the Age of Jackson was in many ways a strange, haunted place, a twilight zone which Tocqueville reconnoitered in advance of its native sons Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville.

For two weeks in December 1831 Tocqueville and Beaumont were stranded in Memphis, Tennessee, on a stretch of the Mississippi river that had frozen over. Tocqueville’s biographer Andre Jardin relates that they were “patient about their misfortune, hunting parrots in the forest in the company of Chickasaw Indians, one of whose villages were nearby.” On Christmas Eve the cold spell broke, just as a providential steamboat arrived from New Orleans. The Frenchmen joined other travellers in clamoring for the captain to turn back to New Orleans, arguing that the river was still ice-bound to the north. Writing to his mother in a letter dated Christmas Day, Tocqueville pictures the scene: “As we were parleying . . . on the river bank, we heard an infernal music resound through the forest; drums were beating, horses whinnying, dogs barking. At last a great troop of Indians appeared, old men, women, children, baggage, the whole led by a European . . .” It was a Choctaw Indian tribe being deported from the land of their ancestors for resettlement west of the Mississippi, under the authority of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed into law by president Andrew Jackson. Needing transportation downriver, they were taken on board the steamboat, whose captain had agreed to head back to New Orleans. “There was a general air of ruin and destruction in this sight, something that gave an impression of a final farewell, with no going back; I couldn’t witness it without a heart.

“The Indians were calm, but gloomy and taciturn. One of them knew English. I asked him why the Choctaws were leaving their country. ‘To be free,’ he answered. I couldn’t get anything else out of him. Tomorrow we will set them down on the Arkansas wilderness. I must confess it is an odd coincidence that we should have arrived at Memphis in time to witness the expulsion, or perhaps of the last vestiges of one of the oldest and most famous American nations.”†

Tocqueville shared the racist prejudices of his time, and many passages and deliverances in the chapter on “The Present and Probable Future Condition of the Three Races That Inhabit the Territory of the United States,” which concludes volume I of Democracy in America, make for uncomfortable reading. Yet the young oracle deplored the combination of false promises, trinkets, alcohol, and barely veiled threats that sped the Indians’ departure. “These are great evils; and it must be added they appear to be irremediable. The Indian nations of North America are doomed to perish, and that whenever the Europeans shall be established on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, that race of men will have ceased to exist.”

Obviously, this is not one of Tocqueville’s prophetic passages. The Indian nations have endured. Is the following another place where he gets America wrong? A footnote in the penultimate chapter of Book I, which is generally considered to be the sunnier volume of Democracy in America, appears under the heading: “Principal Causes Which Tend to Maintain the Democratic Republic in the United States.” In its entirety:

The United States has no metropolis, but it already contains several very large cities. Philadelphia reckoned 161,100 inhabitants, and New York 202,000 in the year 1830. The lower ranks which inhabit these cities constitute a rabble even more formidable than the populace of European towns. They consist of freed blacks, in the first place, who are condemned by the laws and by public opinion to a hereditary state of misery and degradation. They also contain a multitude of Europeans who have been driven to the shores of the New World by their misfortunes or their misconduct; and they bring to the United States all our greatest vices, without any of those interests which counteract their baneful influence. As inhabitants of a country where they have no civil rights, they are ready to turn all the passions which agitate the community to their own advantage: thus, within the last few months, serious riots have broken out in Philadelphia and New York. Disturbances of this kind are unknown in the rest of the country, which is not alarmed by them, because the population of the cities has hitherto exercised neither power nor influence over the rural districts.

Nevertheless, I look upon the size of certain American cities, and especially on the nature of their population, as a real danger, which threatens the future security of the democratic republics of the New World; and I venture to predict that they will perish from this circumstance, unless the government succeeds in creating an armed force which, while it remains under the control of the majority of the nation, will be independent of the town population and able to repress its excesses.

For most of two centuries Tocqueville’s foreboding footnote seemed to be a misfire. As an aristocrat whose parents had narrowly escaped the guillotine during the Terror of 1793, Tocqueville had understandable reasons for fearing the urban crowd and their “sudden and passionate resolutions.” “To subject the provinces to the metropolis is therefore to place the destiny of the empire not only in the hands of a portion of the community, which is unjust,” he concluded, “ but in the hands of a populace carrying out its own impulses, which is very dangerous.” His whole premise was that the big cities in America would always represent a raucous, mutinous minority whose periodic excesses would need correction by a sober countrified majority.

Tocqueville failed to take into account the spread of universal (white) manhood suffrage in the 1830s and ’40s, in which the “multitude of Europeans,” were included. As the historian Eric Foner reminds us, the Irish, Italians, and Jews, who came during the great immigrations of the 19th and early 20th centuries, were already “white,” in the sense that they were readily naturalized for legal purposes able to vote and intermarry with the native Americans (as the white Anglo-Saxon Protestants were known to themselves). And yet, wrong-headed as it might have seemed to be, in October 2025, Tocqueville’s prediction of urban occupation seems eerily prescient, a bad idea whose time has come.

Trumpism, or MAGA, has battened on the anti-urban prejudice which has been an adaptable and resilient American political tradition since the beginnings of the republic. It was epitomized by Thomas Jefferson in his Notes on Virginia in 1785: “The mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body.” The cultural clash of rural and small town America with the ever bigger city simmered throughout the 19th century, becoming particularly acute in the 1890s, with the complaint against the city and its “mixed multitudes” (Lord Bryce) finding a refined expression in Henry James and Henry Adams, at the same time it was being shouted from the rooftops by agrarian populists like Ignatius Donnelly, who specialized in lurid conspiracy-mongering, dark apocalyptic fantasies, and rural resentments. It was the same in the 1920s—the Jazz Age—when the teeming cities seemed to be prospering indecently, presumptively at the expense of town and country.

In the 1930s and ’40s the broadly egalitarian programs of Roosevelt’s New Deal effectively bridged the ancient divide, enabling his majestic majorities with public works and programs like Social Security that benefited the small shopkeeper, the factory worker, and the department store clerk alike. FDR drew his strongest support from the margins of American society, from intellectuals to “ethnics,” and his coalition was held together by his cunning and charisma, but it was always precarious. In 1948, three years after his death, the Democratic party split three ways. In the years that followed, McCarthyism was in large part driven by an animus against what we now call coastal elites. The divide remained sufficiently bridged through the suburbanization of the mid-century that saw the narrow election of JFK in 1960 and the thunderous majority of LBJ in 1964, but ever since the tumults of ‘60s, the New Deal increasingly appears to have been, in the historian Jefferson Cowie’s phrase, “The Great Exception.” The anti-urban prejudice, which had been inspired by industrialization in the 19th century, would be renewed by deindustrialization in the late 20th, and also by a widening gap in the fortunes of those who were college educated and those who were not. (The gap now seems to be closing again, but not in a way that encourages solidarity.) Political scientists who maintain that the present divide is a fairly recent development, citing the electoral performances of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, need to pull back the curtains to take in the larger picture, in which ancient antagonisms were always latent and ready to be exploited.

FDR drew his strongest support from the margins of American society, from intellectuals to “ethnics,” and his coalition was held together by his cunning and charisma, but it was always precarious.... ever since the tumults of ‘60s, the New Deal increasingly appears to have been, in the historian Jefferson Cowie’s phrase, “The Great Exception.”

In 2025, like a recurrent nightmare, it seems that the unruly descendants of “freed blacks” and the unwelcome immigrants lodged in “sanctuary cities” must be dealt with, firmly and repeatedly. Since August, when a teenaged member of Elon Musk’s DOGE team in Washington, D.C., was injured in an apparent car-jacking that was not job-related, president Trump has dispatched—or threatened to dispatch—National Guard troops or other federal agents to ten big cities with varying rationales: sometimes to protect ICE facilities, but more often to combat a vicious crime-wave that his critics believe is wildly exaggerated if not outright hallucinatory. “Portland is burning to the ground,” “Chicago is a killing field,” and so on. “This will go further,” Trump said in August. “We’re going to take back our capital . . . and then we’ll look at other cities also.”

From California to the New York island, as Woody Guthrie sang, the boots are on the ground, be they federal agents or the conscripted National Guard. Invariably, the cities are in states with Democratic majorities; typically, they are governed by Democratic mayors, often Black; invariably, they have been described as crime-ridden to the point of being ungovernable. But then, per the president’s domestic counselor, Stephen Miller, “The Democrat Party is not a political party. It is a domestic extremist organization.” And Trump, after all, never promised to govern with malice toward none.

Just this month howitzers were fired over Interstate Five in Southern California at a celebration of the 250th anniversary of the Marine Corps, attended by the vice president, and debris fell on the vice president’s entourage. ICE has descended on African street vendors on Canal Street in Manhattan, presumptively undocumented, and unabashedly selling knock-offs of Gucci handbags and other counterfeits. San Francisco has been spared an occupation after an intervention with the White House by the mayor and local plutocrats, including modest, self-effacing Marc Benioff; fellow feeling for its billionaires prevailed this time, but the city by the Bay was plainly on a probationary status. Nothing, in the president’s monarchical conception of his office, would prevent him from, in his own words, doing anything he wanted. But if the cities are being occupied, it’s not by the agents of an aroused majority, as Tocqueville imagined, but what looks to millions of America very much like a junta.

What long seemed to be, if not pillars of the firmament, at least reliable features of the American scene, are like wrecks of a dissolving dream, as in Shelley’s poem or Christopher Nolan’s Inception: birthright citizenship, the Posse Comitatus Act, federalism, the separation of powers (with the Speaker of the House playing the lackey in the government shut-down), demolition of the East Wing of the White House. Stuck somewhere inside of Mobile, the ghost of Alexis Charles Henri Cleril comte de Tocqueville (1805-1859) has the Memphis blues again.

*Democracy in America was published in French in two volumes, 1835 and 1840. Quotations below are from the contemporaneous Henry Reeve translation, revised by Francis Bowen, corrected, edited, and with an introduction and notes by Phillips Bradley (New York: Knopf, 1945).

†The Choctaws were one of the Five Civilized Tribes, so called by American authority because one or another had adopted European practices, from the alphabet and farming to the enslavement of Blacks. Tocqueville gives a wordier and less vivid account of his departure from Memphis in his book, while adding a poignant detail. “The Indians had all but stepped into the bark that was to carry them [across the river], but their dogs remained upon the bank. As soon as these animals perceived that their masters were finally leaving the shore, they set up a dismal howl and, plunging altogether into the icy waters of the Mississippi, swam after the boat.”