[drop-cap]

Gavin Lambert struck an unusual tone—at once ironic and affirming—across The Slide Area (1959), his first novel and an unassuming masterpiece of Los Angeles fiction. Its narrator pairs a rare clarity of vision with an even rarer warmth of engagement: he manages to be sharp without being cutting, and sympathetic without being indulgent. If The Slide Area does not deliver the more familiar satisfactions of LA noir in its “scenes of Hollywood life” (as its subtitle has it), it is not because there are no crimes committed—there will be at least one murder, one case of statutory rape, and one case of fraud—but instead because Lambert’s interest lies elsewhere. As Gary Indiana has remarked of Lambert’s fiction more generally, it works to solve “mysteries of personality rather than crimes.”

The novel opens with its screenwriter-narrator “looking out of the window and wondering why the world seems bright yet melancholy.” The world outside his studio office is bright—bright with sunlight, bright with “neat flower-beds dustily brilliant in puce and yellow,” bright with the artifice of the constructed sets nearby, bright with the modern-day convertibles and other “princely roadsters” that make visible the wealth of Hollywood. Yet the scene is also suffused with melancholy—a melancholy that is less easily pinned down and grasped. The faces of executives burst into sweat at a nearby newspaper rack; the screenwriter sits in his office, his tray of finely-sharpened pencils going unused. The first “mystery of personality,” then, is the mystery of Hollywood’s ambience: Why is it that, for all the happy endings generated and filmed on site, an air of anxiety pulses beneath the smiles and laughter?

Over the next two-hundred-plus pages, the narrator will be our guide into that enigma. He’ll criss-cross the neighborhoods of Santa Monica and Venice, the Hollywood hills and the Hollywood flats, often with the goal of helping a friend—or would-be friend—in need, acting as an accomplice to their far-flung desires. His ride will be a “fog-grey seventy dollar 1947 Chevrolet” with a “battered front I refuse to have mended.” He throws himself in with the damaged; in his world, they are the ones with character.

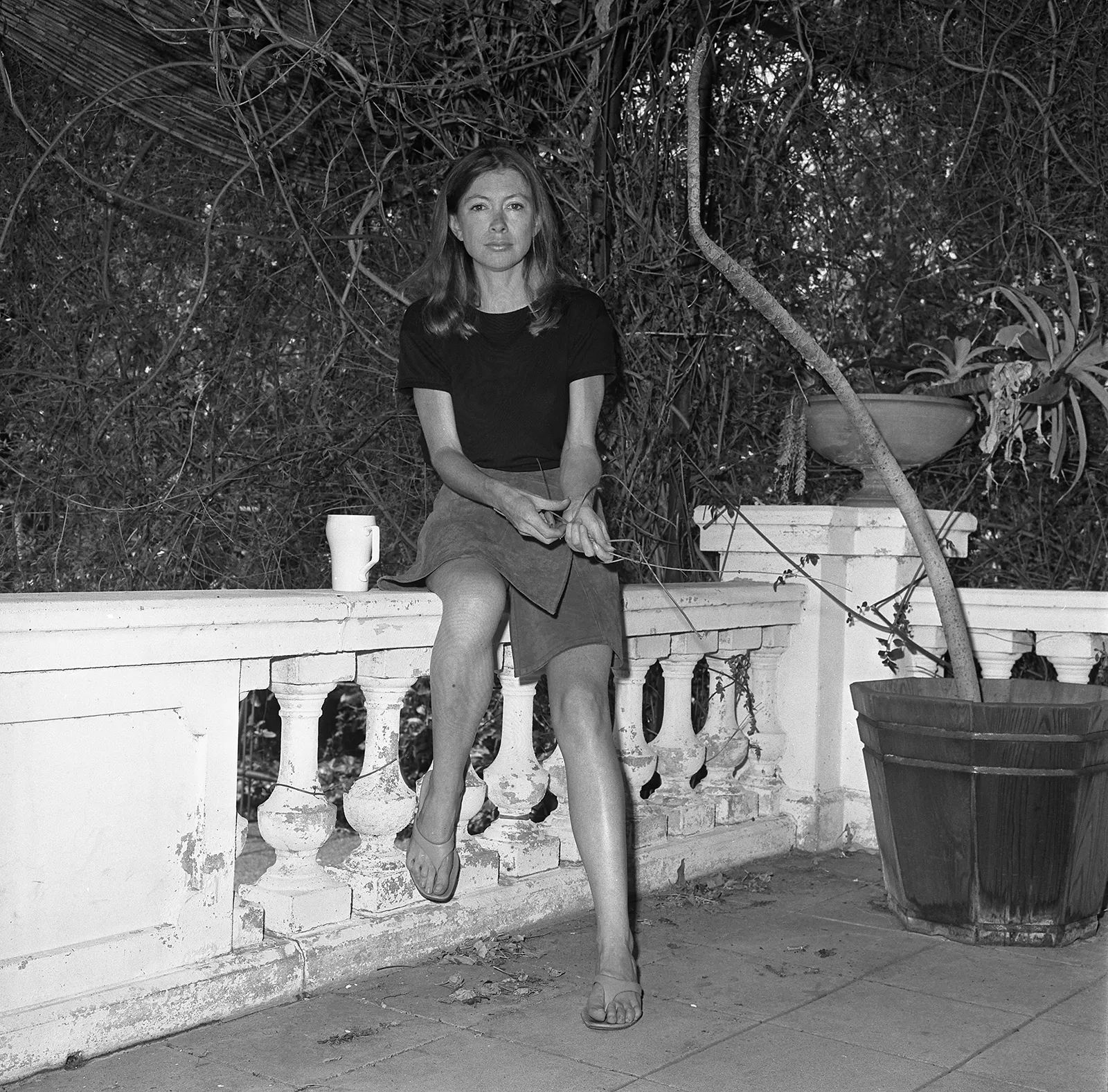

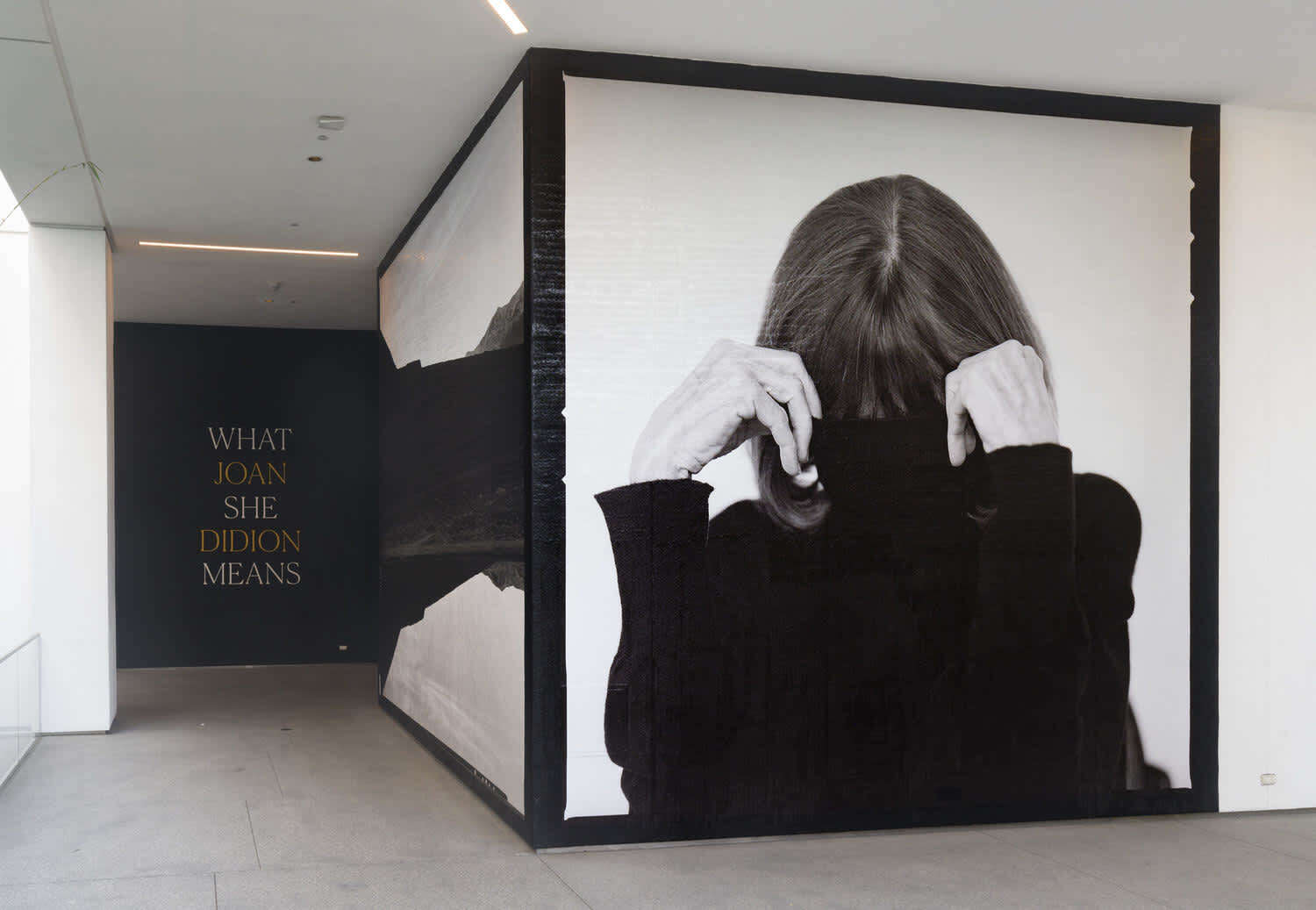

The controlling metaphor of the novel—Los Angeles as a “slide area” where the ground is always shifting under one’s feet—is handled with a light touch. “Sliding” can be fun as well as dangerous; the playground slide offers one of the most basic childhood pleasures, and Lambert is not so serious as to disown childhood delights. Eight years after The Slide Area, Joan Didion would use a more dismal, high-modernist metaphor—the slouch of Yeats’s rough beast “slouching toward Bethlehem”—to evoke the sense of American decline that she saw in the stirrings of the Californian counterculture. “Slouch” captured so well the nature of Didion’s distaste: she saw a failure of stance, a failure of moral posture, that correlated with a larger spinelessness, one made even more unseemly because its exponents dressed themselves up in the rhetoric of innocence.

Lambert is considerably less judgmental and infinitely less apocalyptic than Didion. The Slide Area crisply articulates the failings of Los Angeles (“Los Angeles is not a city, but a series of suburban approaches to a city that never materializes”) even as it finds a great variety of pleasure in their acquaintance. The “slide area” of the title refers, on a literal level, to a stretch of the Pacific Palisades, marked with signage that notes how it threatens to fall into the sea. When it does collapse in the novel’s opening section, however, the result is a parable of resilience, not declension. The scene looks grave at first—“the legs of old ladies” are seen “sticking out” from “a great pile of mud and stones and sandy earth.” But once rescued by emergency workers, these three elderly picnickers merely shake “little clods out of their hair” and declare themselves “quite all right” to the crowd. One says, “I was taken completely by surprise!” It’s a typically Lambertian moment, rich with a doubleness of feeling. The moment rings with a sense of irony—didn’t she notice those large SLIDE AREA signs when she chose the slope as the site of her picnic?—and a sense of amazement: the astonishment of having one’s life, a life of picnics and tablecloths and air cushions, turned willy-nilly into an adventure story.

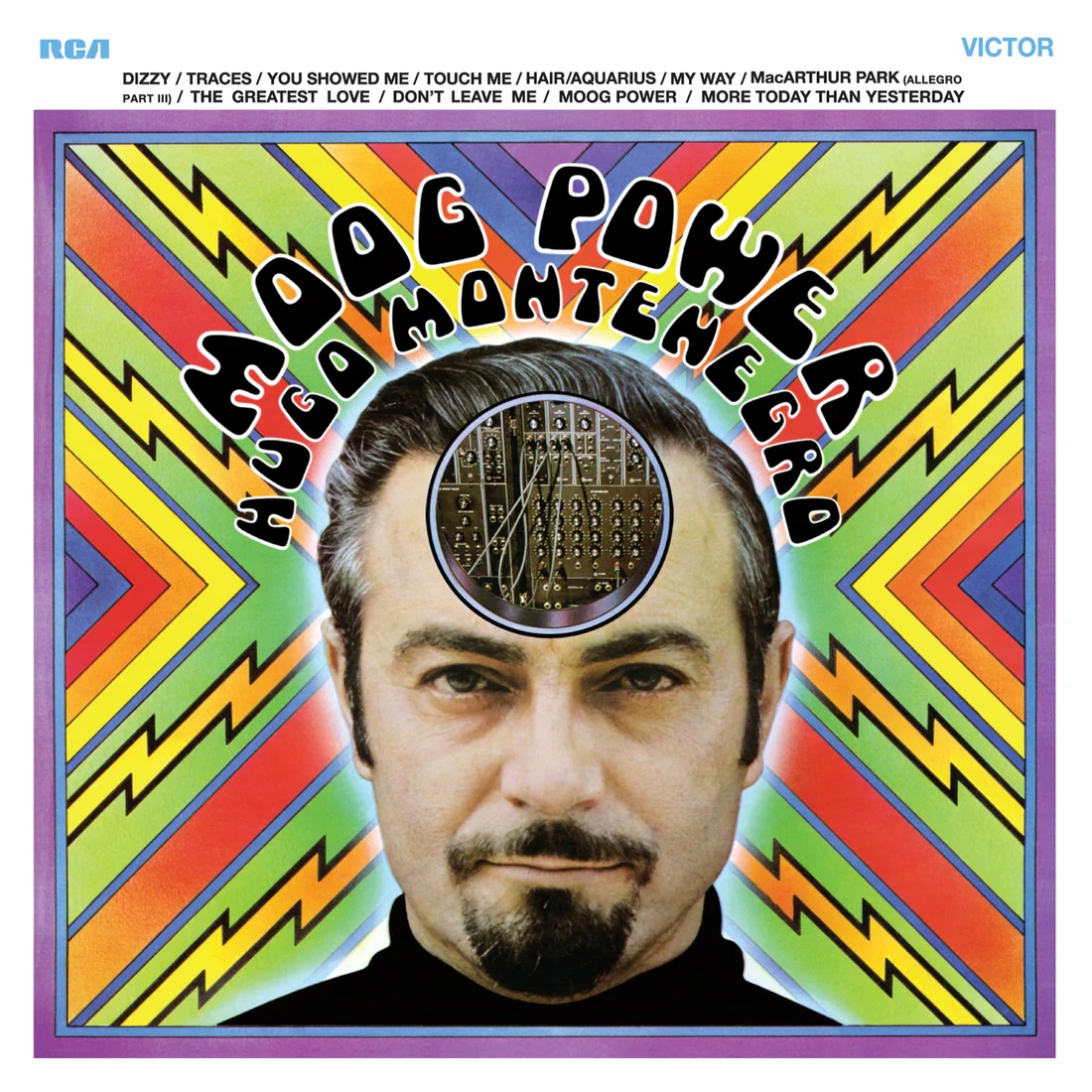

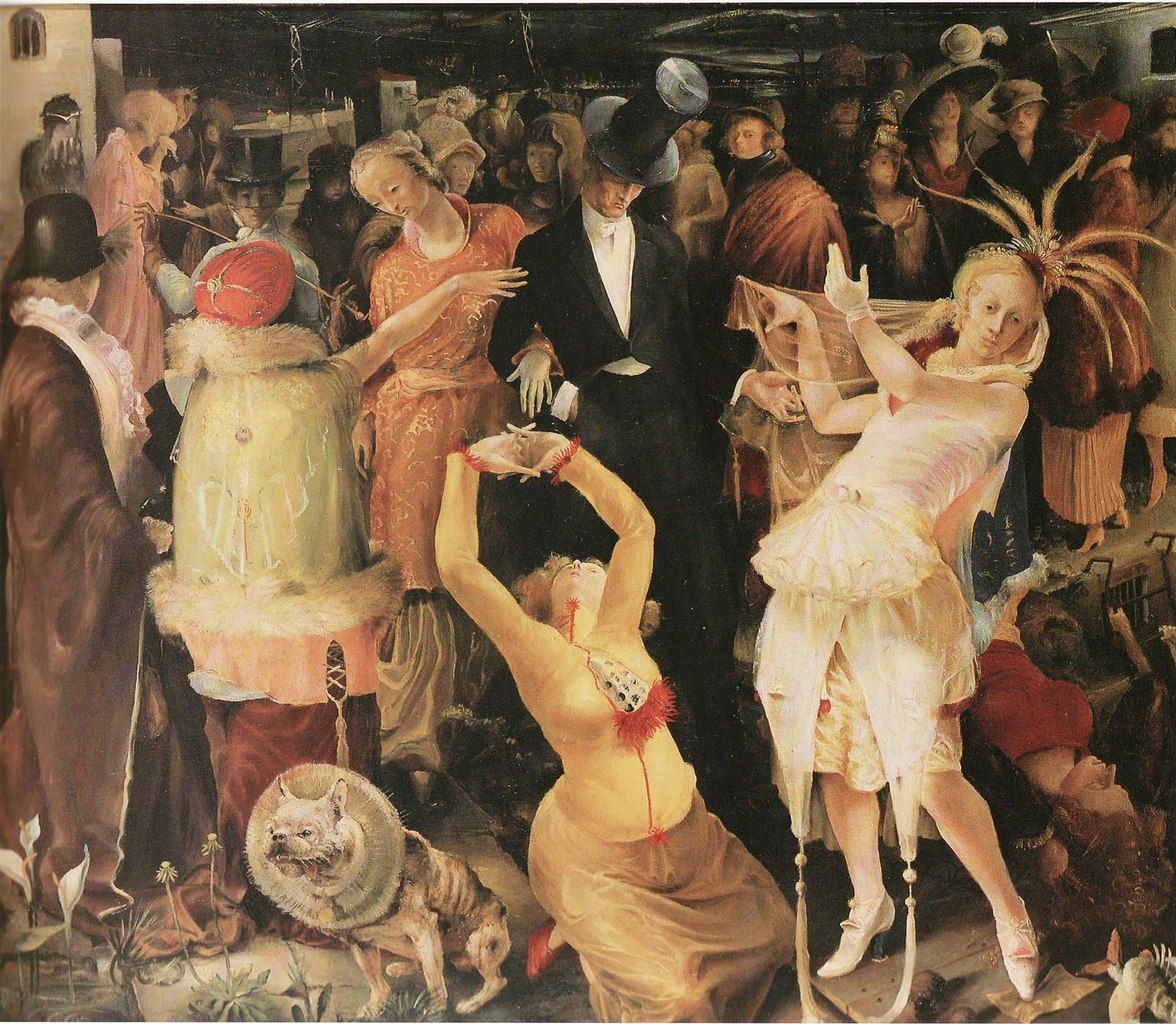

Another quick signal of The Slide Area’s distance from noir comes in its early handling of a murder. The narrator locates himself in the southern end of Santa Monica, a neighborhood that is “rather slatternly and interesting.” In fact, Santa Monica may be interesting because it is slatternly—messy and dirty and populated by women who are open about selling their wares. In that life, there is real danger: The narrator discovers that a friend of his, a woman named Hank, has been murdered by a john. But the liveliness of that world—of a bar called The Place, where the narrator, Hank and her sister Zeena have been regulars—is unextinguished. The tone of the scene tilts, against the grain, toward the comic. The narrator is impressed into acting as a go-between between Zeena, who is drunk and wild with grief, and a straight-laced German nun, from the hospital where Hank has died, who cannot bear departures from sobriety. Meanwhile an old man in a Panama hat dances with his cane as the jukebox plays a song identified by the narrator as “Mackie Messer”—better known to us as “Mack the Knife,” and not incidentally a song about a killer. The show goes on.

Lambert is considerably less judgmental and infinitely less apocalyptic than Didion. The Slide Area crisply articulates the failings of Los Angeles even as it finds a great variety of pleasure in their acquaintance.

The Slide Area drew on Lambert’s gratitude to Los Angeles for having offered him a home—an escape-hatch from the repressive British milieu of his childhood and early adulthood. “In Britain,” he remembered, “it was bad form to be passionate. In American films, nobody drew back from caring. And, as a nine-year-old schoolboy, I sent a rather grubby postcard to Mae West, and she signed it and sent it back. I saw the American stamp, and Paramount's logo on its corner. So I knew Hollywood was real.” His larger awakening to the pleasures of Hollywood dovetailed with his sexual awakening, at the age of 11, while attending a prep school located on the grounds of Windsor Castle, where his music teacher became his lover. “Soon after falling in love with him,” Lambert recalled in his memoir, “I fell in love with the movies.” His lover-teacher often took him to the cinema on afternoons when there were no classes, introducing him to Warner Brothers noir as well as “the bright, voluptuous world of MGM.”

Eighteen months later, Lambert was taught a lesson about the perils of being gay in prewar Britain. His teacher-lover and two other queer teachers were fired by his school; around the same time, he discovered that his queer cousin, who had died some years previously, had in fact committed suicide. The young Lambert became convinced that he “had to live in a secret world.” Against the strictures of his childhood, he came to treasure “the illusion of movies, especially the world according to MGM, where the pursuit of happiness and the blessings of liberty were so confidently taken for granted.”

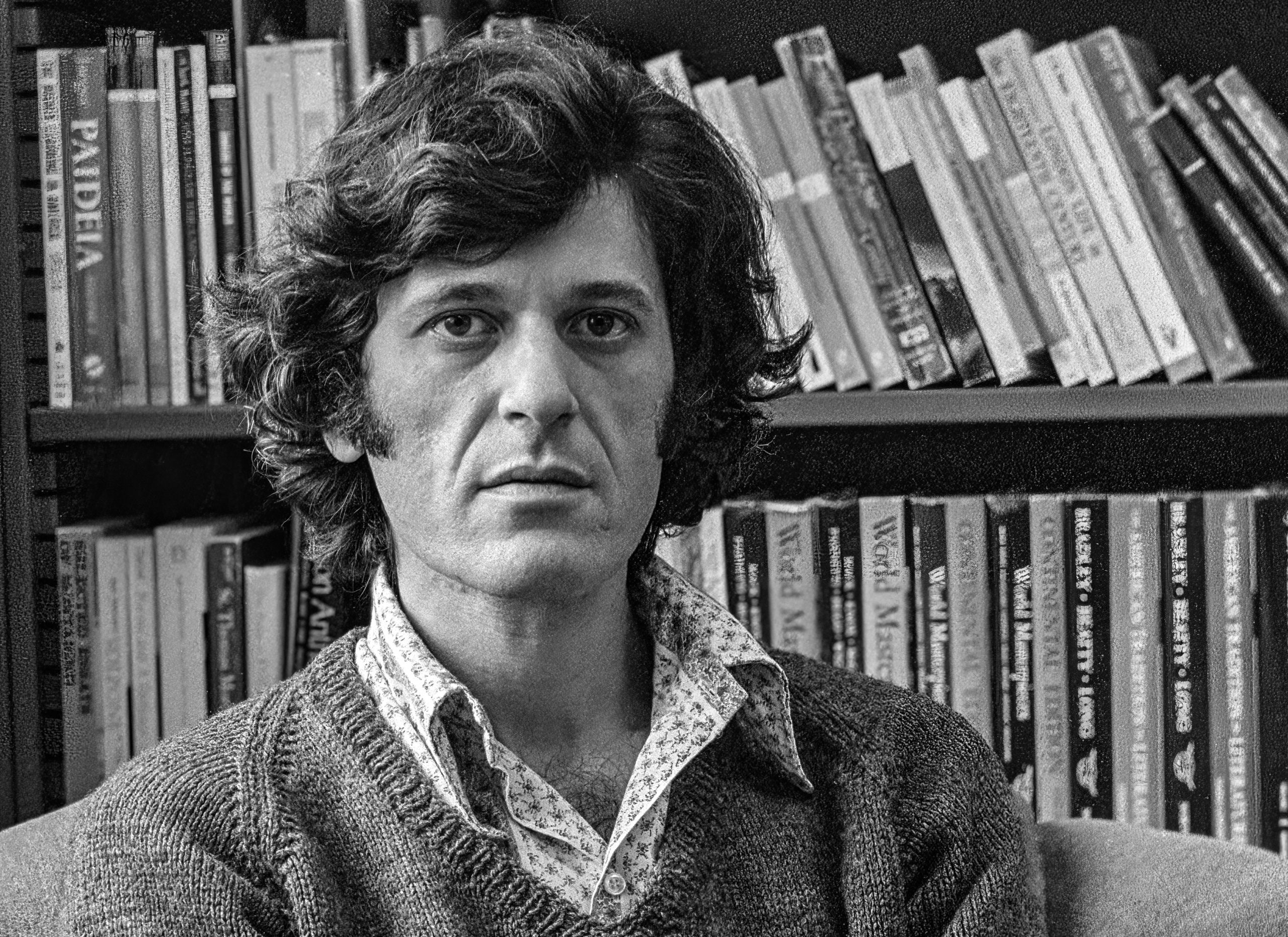

By the mid-1950s Lambert had carved out an iconoclastic role for himself in the world of British film. He revived the British Film Institute magazine Sight and Sound as its editor; he took up arms with the directors Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, and Tony Richardson and founded the British Free Cinema movement, which promoted a new wave of documentary films, more personal and focused on the lives of the working-class; and he wrote and directed Another Sky, a lyrical film about a British woman’s passion for a Marrakech street musician, shot on location in Morocco with a small cast of British actors and Moroccan non-professionals. Lambert’s life took a fateful turn when he met Nicholas Ray, fresh off directing Rebel Without a Cause and distraught still over the death of its star, James Dean. The two spent the night together in Ray’s hotel bedroom; shortly afterward, Ray watched Another Sky and was moved to hire Lambert as his assistant, starting with his film Bigger Than Life.

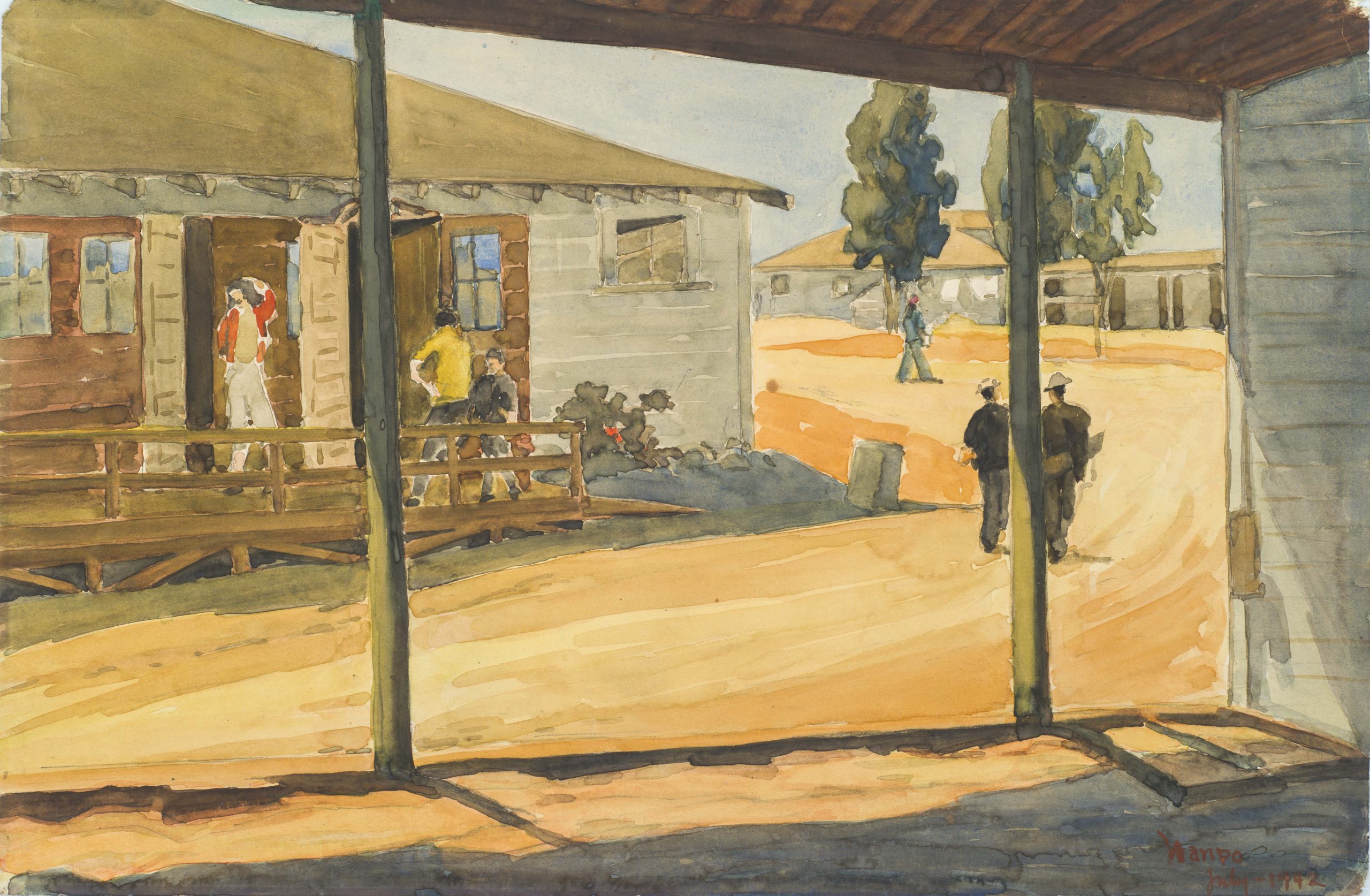

Through his work with Ray, Lambert came to understand Hollywood’s rhythms of work, and the sharp dealings between producers, directors, actors, agents, and publicists, all chasing the lure of success. (Later Lambert would become a successful screenwriter in his own right, nominated for Oscars for his work on Sons and Lovers and I Never Promised You a Rose Garden.) He also became acquainted with LA from top to bottom, and felt connected to the rootlessness he perceived in the city: When, early in his stay in LA, he saw a house being towed down a street to its new destination, he took the image as a mirror of his own experience. After a little while, he felt himself stockpiling, in his mind, “faces, bodies, voices, lives: movie people, beach people, underside people living in trailers and decrepit clapboard bungalows, world-wise European exiles, naive refugees from Oklahoma and Louisiana, pickups in bars.”

These characters would come to populate The Slide Area, but it was Ray’s disintegration that, through an ironic chain of circumstances, led Lambert to begin drafting the novel. Drinking and depressed, Ray was falling apart while working on his foreign-financed war film Bitter Victory—romantically involved with a heroin addict with a violent temper, and so drunk he did not realize how much money he was losing at night at the casinos. Ray’s French producer Paul Graetz was alarmed and made a ploy to control his errant director by clamping down on his assistant, whom he saw as loyal to Ray and not himself. He informed Lambert and Ray alike that Lambert would only be paid for his work on the film—money he desperately needed—if Ray returned from Tripoli having completed the location shooting.

A pawn in this battle between producer and director, Lambert had six weeks to himself at the Hotel Raphaël, near the Champs-Elysées, where, on Graetz’s tab, he threw himself into the LA novel he had been carrying in his head. He had the intuition that, just as Christopher Isherwood had constructed his 1939 novel Goodbye to Berlin from a fragmented set of interconnected episodes, so his novel would shift between characters and scenes, not resting with any one central protagonist or setting. He also repurposed a wry, highly visual, and economical style of narration: He took Isherwood’s “I am a camera” aesthetic and adapted it for the actual world where movies were made, as inflected by his own experience of Los Angeles as a city of refuge. The Slide Area was built out of scenes of unforced and somehow warm witness.

He also became acquainted with LA from top to bottom, and felt connected to the rootlessness he perceived in the city: “faces, bodies, voices, lives: movie people, beach people, underside people living in trailers and decrepit clapboard bungalows, world-wise European exiles, naive refugees from Oklahoma and Louisiana, pickups in bars.”

In his book on the director George Cukor, Lambert wrote that, if the director’s life and work were to be summed up in one word, it would be “discreet,” which “implies delicacy, prudence, and something enigmatic. The ‘I’ exists but doesn’t care to advertise itself.” The Slide Area is held together by its discreet narrator, a keen observer who is also a recessive enigma. He is infinitely more private than the many characters he meets, who often take no more than a nudge to spill their secrets, ambitions, and theories of how the world works. Since we rarely gain insight into what the narrator specifically wants or desires, the action of the novel seems to fill that vacuum: what he most desires, it appears, is simply to know these other people, and through them to understand the city that supports or fails them. He feels as reliable as a first-person narrator can be. While quick to catch and register ironic details in the scenes he dramatizes, as a character he largely acts as a sounding-board for the wide cast of dreamers he meets, his sympathy allowing them to make the best case for their aspirations, or to give voice to their doubts and qualms.

A brief summary of those aspirations suggests how easily they might have been mocked in the satirical manner of, say, Evelyn Waugh in his LA novel The Loved One. We meet a former British schoolmate, who desires only to sun himself on the beach and supports that lifestyle by living with a wealthy man he resents (“Nukuhiva!”); a blind and nearly deaf dowager-countess, still in love with the lost world of aristocratic Austro-Hungary and eager to go on one last Grand Tour, her declining senses and fortune be damned (“The End of the Line”); a middle-aged Hollywood star (based on Joan Crawford) seeking to revive her career through manipulation and force of will (“The Closed Set”); a fourteen-year-old midwestern runaway with a bottomless faith in her future stardom (“Dreaming Emma”); and a scion of a powerful Hollywood agent, erotically drawn to men and women, who drifts from one scrape to another (“Sometimes I’m Blue”). The novel’s main characters tend to be either creatures of ambition or creatures of pleasure, and in the loose structure of The Slide Area serve as foils of one another.

Of Emma Slack, the runaway and would-be starlet, the narrator remarks:

There was a kind of fanaticism about Emma, and perhaps this made her really helpless. In a city full of dreamers, she clung with such fierceness to an obviously fragile dream. When I thought of that, she struck me as about the most impermanent person I could imagine in the world.

From one angle, Emma is the embodiment of “appalling, cruel, perfect egocentricity”—the egocentricity of the Hollywood dream. From another, she is the prisoner of her dream, “helpless” under its power: Because she is so desperate to be “noticed” by someone—a yearning that she traces to wanting to be noticed by God as a child—she is in danger of evanescing if no one does. Resonantly for our own moment, Emma comes to approach her life transactionally, with her young teenage girl’s body being the most prized commodity she has to offer. In a literally bruising arc, she both achieves her dream and is made unrecognizable to herself.

The Slide Area’s hedonists are also forced to grapple with getting what they wished for. Although the main hedonists—the sun-loving Mark and the ever-drifting Clyde—happen to take male partners, the novel takes their sexual orientation in stride: Rather than dramatize, say, how queer Angelenos were subject to police raids on their gathering places, The Slide Area’s queer characters are not particularly embattled or anguished because of their choice of intimate partners. (In a 1970 interview, Lambert said, “The only works of art that treat the subject of homosexuality are the works of art that don’t ‘treat’ it. I believe in a novel or a play that doesn’t make a point of the character being homosexual.”) If they struggle, as Mark does, with his “stupid unpromising life,” that is because, having shucked off the models of success passed down from their parents’ generation, they are engaged in the elusive project of making happiness sustainable. In Clyde’s case, he suffers from a surfeit of opportunities for extending himself—a relationship with a devoted and more conventional male lover; a relationship with a more irascible and mercurial female lover; a lucrative partnership in his father’s talent agency that awaits him—and an utter lack of inner direction.

Through the tale of Clyde and his frustrated would-be lovers, The Slide Area explores the destructive edge of the search for pleasure. The sun-tanned, athletic Clyde has two features that give an extra charge to his interchanges with others: “deep rapt ultramarine eyes” and an “extraordinary smile” with a “quick nervous radiance.” (For the fortune-blessed Clyde, even his insecurities are radiant and work to deepen his charm.) Yet Lambert gives this section a subtly unusual structure: the narrator splits his time between the charismatic Clyde, unhappy with his lovers and unhappy without them, and the flavorless, homely Walt, who trails Clyde while never coming to grips with how he has lost himself in an ill-defined relationship that has cost him his self-respect.

The curious effect of the storytelling is to drain Clyde of his charisma and to invest Walt with an enigmatic pathos. Clyde does not surprise: He is petulant, railing like Holden Caulfield against all the “phoneys” he meets, and leaving others to clean up the various messes that he makes. His inner restlessness is real, and not to be dismissed, especially since it speaks to a larger anomie among the golden boys of Los Angeles. But it is Walt, the lover as fan, whose fuzziness draws the narrator’s curiosity and sympathy. Their last conversation is both meandering and poignant, as the abandoned Walt turns to thoughts of home and of escape. A seemingly random set of remarks from Walt as they drive along the coast—“My father used to play checkers in the evenings. I never could stand the game. They’ve had a lot of rainstorms in Ohio recently”—leaves us wondering what he left behind in Ohio, what he misses, and what he was trying to escape. There is a pause in the story: “This is the last remark he makes for some time,” the narrator tells us. Ever-discreet, he allows us to try to fill in the blanks.

“The Slide Area was published to good reviews at the end of 1959,” Lambert wrote matter-of-factly in his memoir. It is a moment of extreme modesty, typical of Lambert’s own writing about himself, and one that deserves to be corrected by the historian. In fact, The Slide Area—bearing a strong pre-publication endorsement from Christopher Isherwood himself (“the most truthful stories about the film world and its suburbia I have ever read”)—was met with extraordinary acclaim by a set of reviewers who, even more remarkably, put their finger on the delicacy of Lambert’s accomplishment.

From the start, the novel was seen as a breakthrough depiction of Hollywood. “A brilliant piece of work, terse, compassionate, and beautifully made,” wrote the Times Literary Supplement. “It earns a place on anyone’s shelves along with Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon and Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust.” The novelist Kingsley Amis named the novel one of his favorite books of the year. Perhaps the most perceptive review came from Dilys Powell, the doyenne of British film criticism, in the film journal Lambert had previously edited. In Sight and Sound Powell called The Slide Area “the best fiction, the best book I have ever read about Hollywood,” and explained how it stood out from the pack:

The people who write about Hollywood, those who are not idolaters, are usually full of hatred; here is an author who has the faculty, rarer than you might suppose, of simply liking. Difficult to fault his style with its precise communication of inconsequent talk, its mingling of melancholy and wry fun. It is the strength of the book that it expresses not merely affection for the figures on the impermanent slopes, but a protective feeling which makes their danger the more touching.

The faculty, rarer than you might suppose, of simply liking: Powell captured how Lambert departed from the entrenched positions of writing about LA, the positions of LA’s boosters and its detractors. Instead he became a friend to the city—or, more specifically, a friend to those at risk in it. With the gifts of his meticulous attention and his discretion, he moved us to see them in full—the quality of energy they brought to their relationships; the gap between their self-image and their actions, sometimes absurd and sometimes horrible; their vulnerability—and to care for them in whatever way we chose.

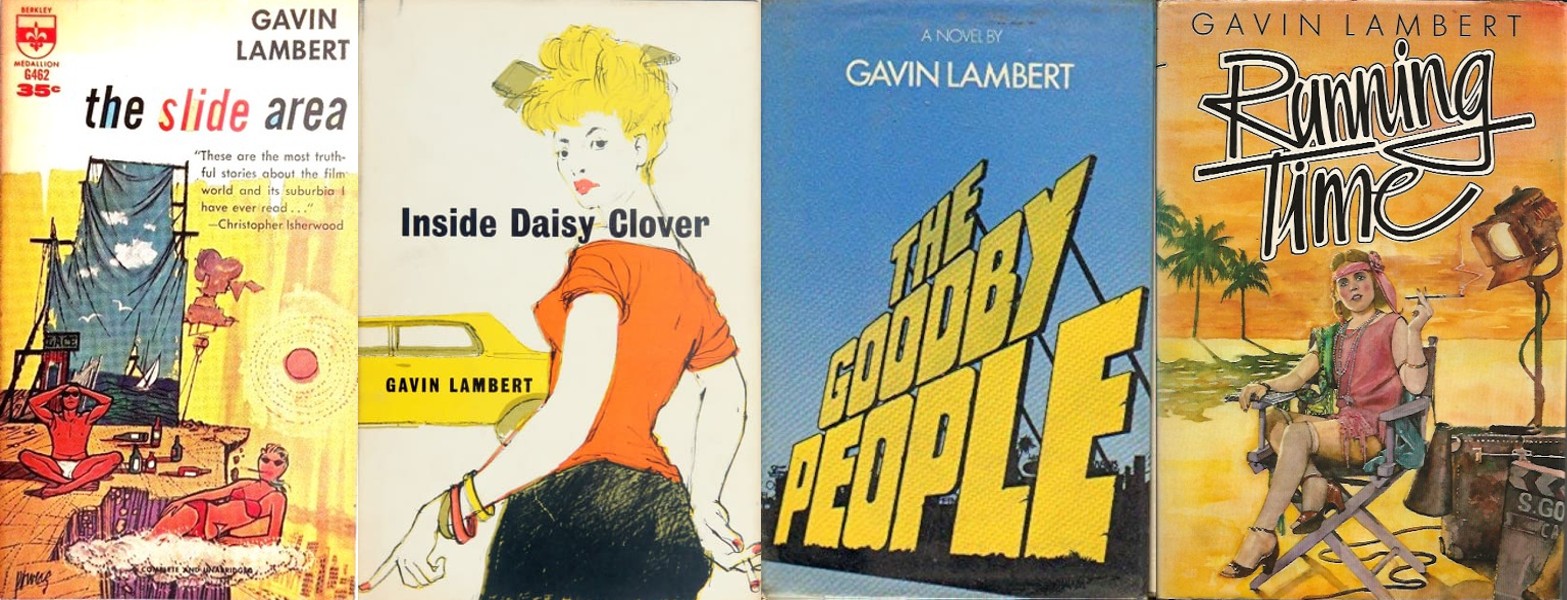

In 1963, in an essay on LA for Harper’s Bazaar, Lambert proposed that “Once you understand this place as a kind of Theater of the Absurd brought to life, you see both its appeal and its meaning.” This vision of the city—which drew out the incongruities on offer in it and refused to lampoon them—helped Lambert become one of the great chroniclers of LA on the page. In the realm of fiction, he aspired to compose “something loosely and very modestly Balzacian…[a] kind of Human Comedy,” and ended up completing what he called his “Hollywood Quartet,” comprised of The Slide Area;Inside Daisy Clover (1963), about a teenage movie star struggling to grow up in the teeth of the industry; The Good-by People (1971), an interlinked trio of novellas set in the aftershocks of the counterculture; and Running Time (1983), centered on the taut relationship between a Hollywood star and her mother. Meanwhile, Lambert distinguished himself as a biographer of silent and classic Hollywood, delving into industry archives and writing novelistically about the lives of Alla Nazimova, Norma Shearer, and his friend Natalie Wood. Between the subjects of Nazimova and Wood, he encompassed the entire span of stardom before the “New Hollywood;” ever-industrious, he also managed to complete books on the making of Gone with the Wind and the life of a fellow British screenwriter (The Ivan Moffat File). Shortly before Lambert’s death, in 2005, at 80, the film historian David Ehrenstein described him as “the person who probably knows more about the Golden Age of Hollywood than anyone else alive.”

Why, then, is Lambert himself a recessive presence in the literary history of Hollywood, with The Slide Area out of print in the US despite its regular presence on lists of the best Hollywood novels, and despite the welcome recent republication, by McNally Editions, of its companion novel The Good-by People?

It may be that the same qualities that make The Slide Area so special—its balance of acuity and discretion, its buoyancy, its trust in the capacity of its readers to come to their own judgments of the world it evokes—are also what make it untimely. With its focus on the human appetite for celebrity, the dream of being known and thereby loved, it forecasts our current world of influencers and other social-media personalities, but its sensibility is too wry to have even a whiff of self-promotion to it, and too generous to offer the pleasures of the savage takedown or the hot take. The novel is an artifact of another age, when a queer writer like Lambert might leverage an aesthetic of discretion to model for us how to be a certain kind of friend, never intimate but always on the level, and to draw us into a world of glimmering surfaces and uncertain depths, perfectly described but never judged.