[drop-cap]

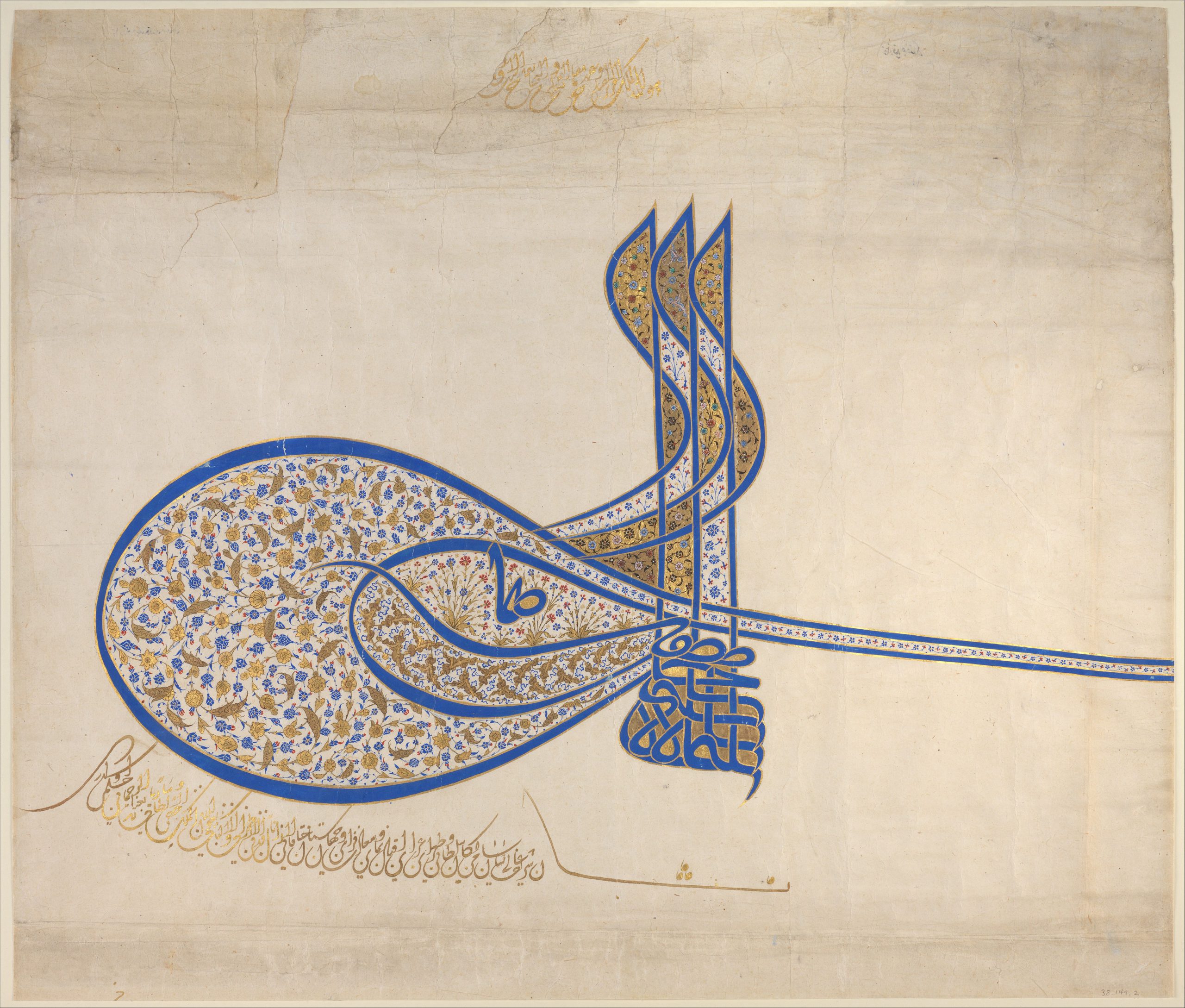

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, while the European “Age of Discovery” proceeded on distant shores, from the Cape of Good Hope to Cape Mendocino, the paths of glory that had led Europeans to the Levant during the Crusades were abandoned to Islam. In 1516-17, in their final conflict, the Ottomans, who had modernized themselves into a “gunpowder empire,” overthrew the Mamluk overlords of Egypt and Syria, consolidating their sway over almost the entire Middle East. It lasted for most of the next four centuries, until their vast derelict empire fell apart during the First World War. Given a mandate to govern by the League of Nations in its aftermath but soon enough finding it a troublesome charge, Britain would abandon Palestine after the Second; it had been a sort of crusader kingdom but much shorter-lived than Latin Palestine in the Middle Ages.

In the 19th century Herman Melville and Mark Twain were among the first American writers to tour the Holy Land, Melville before and Twain after the Civil War. A lonesome traveler, and at thirty-seven in poor health, mental and physical, Melville saw himself or his future self reflected in Jerusalem’s ghastly landscape. In the telegraphic style of his travel diary he wrote, “The color of the whole city is gray and looks at you like a cold gray eye in a cold old man—its strange aspect in the pale olive light of the morning.” A decade later, at the beginning of a fabulous career such as Melville could only dream of, Twain traveled farther, always surprised by how short the distances were, and how puny the famous biblical kingdoms had been. From his Sunday school days: “The word ‘Palestine’ always brought to my mind a vague suggestion of a country as large as the United States. I do not know why, but such was the case. I suppose it was because I could not conceive of a small country having so large a history.” He and his fellow travelers, the “Innocents Abroad” who had come on the ship Quaker City, got as far as Ramleh, “cross[ing] the brook which furnished the stone that killed Goliath,” and after passing a “picturesque old Gothic ruin,” riding “through a piece of country which we were told once knew Samson as a citizen.” Twain was ready to be on his way to Alexandria. “Of all the lands there are for dismal scenery, I think Palestine must be the prince.” He rejoiced when he caught sight of the Quaker City riding at anchor in Jaffa. “It was worth a kingdom to be at sea again.”

In spring 1957, A.J. Liebling, a staff writer for the New Yorker, retraced Twain’s path, reporting from Gaza City at the southern end of what the world now was calling the Gaza Strip. One of the oldest continuously settled places on earth, Gaza was on its way to being one of the most crowded, “a gateway to nowhere,” Liebling called it, “for three hundred thousand people.” Two-thirds had come in flight from the north during Israel’s foundational war with Egypt and the other Arab states in 1948-49; they were stopped by the desert, on a snippet of land that Egypt occupied at the cease-fire but never annexed. As Liebling explains, in the vocabulary of the time, “It is unlikely that they would have wished to cross it in any event, since they were Palestinians, not Egyptians, and their breeds are as incompatible as the regions are different.”

A year before, during the Suez War of 1956-57, Britain, France, and Israel secretly concerted an invasion of Egypt by Israel, intended to restore Britain’s control of the Suez Canal, which the Egyptian strongman Gamal Abdul Nasser had nationalized. The unavowed allies anticipated that a successful demarche would lead to Nasser’s overthrow, which, for various reasons, all desired. (The French believed he was giving aid and comfort to the rebels in Algeria.) The Israeli troops that occupied Gaza in the course of the war prepared to leave after four months, unreluctantly turning over its swarming refugee camps to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). For thousands of years the Gaza Strip had caught the acquisitive gaze of Empire, but for now it was averted.

Most of the refugees in Gaza had come from no great distance; many of them could glimpse their former homes from the Strip’s modest heights.... Israel insisted that the issue could be resolved only after a comprehensive peace agreement had been agreed upon with the Arab nation, something which has yet, in the 21st century, to happen.

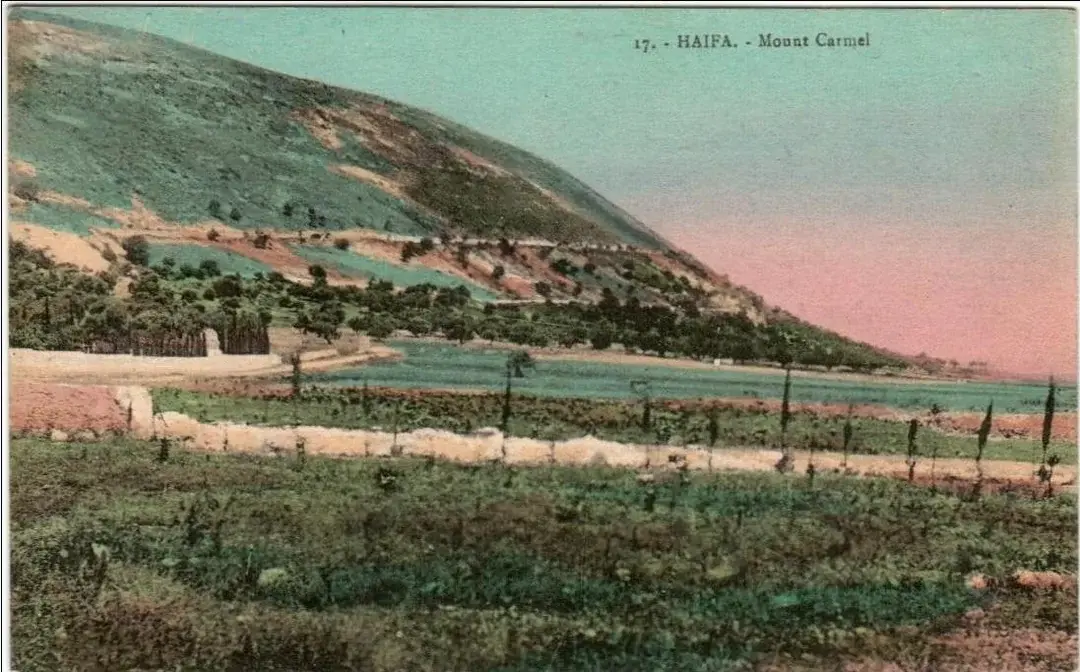

Rotund owl-eyed Abbott Joseph Liebling was not a roving correspondent in the muscular mold of his sometime confrere Ernest Hemingway, but he had seen a good deal of war as a Reporter-at-Large for the New Yorker: the fall of Paris, the Blitz, the French underground, Algiers, Tunisia, D-Day, the road to Paris. It might be that his dispatch, date-lined March 16, 1957, was the first in the Western press to picture Gaza as a prison. “The Strip is not a forbidding prison; most of it is agreeable but unspectacular country, flat except for a low ridge, called Ali Muntar, north and east of Gaza town. From Gaza south, it is green for twenty miles, then begins to go shabby and semi-desertic, and tails off into bleakness at Rafah, the last village.” How did the prisoners come to stay in this airy prison-house? Here Liebling indulges in a poignant might-have been:

“Had peace ensued, or had the Israelis won the Strip before the armistice [in 1949], the refugees would have been reabsorbed into Israel, returning to their homes within weeks or months. But no treaty followed the armistice, which was never more than an imperfect cease-fire.” Here, as with any alternate history, one must contend with the implacability of what actually did happen. Would the newly established state of Israel actually have readmitted the Palestinian refugees in 1949 or soon thereafter? World opinion, so far as it followed events, supported their return, but instead the new arrivals remained in camps, confined with the prewar population. It was, Liebling says, “as if the French refugees backed up against the Spanish frontier in 1940 had been held ever since within a coastal enclave from St.-Jean-de-Luz to Bayonne.” But the comparison with the French who fled the advancing German army after the fall of the Third Republic quickly breaks down.

The Germans had come as an occupying power, not as settlers, and the situation of the Palestinians in 1948-49 more closely resembled the vast and terrible dispersions of populations toward the end of the war and during its aftermath: Germans fleeing East Prussia after a thousand years, Tatars from the Crimea packed into boxcars destined by Stalin for a distant exile. Unlike the Germans and the Tatars, most of the refugees in Gaza had come from no great distance; many of them could glimpse their former homes from the Strip’s modest heights. The admission of Israel to the United Nations was assured by the almost immediate recognition by the two superpowers, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. But the vote to admit Israel by the General Assembly was premised by the common expectation that it would concede to resolutions calling for the refugees’ right of return or compensation. Israel insisted that the issue could be resolved only after a comprehensive peace agreement had been agreed upon with the Arab nations, something which has yet, in the 21st century, to happen.

Liebling compares the Gazans in their liminal zone to “people trapped in a submarine at the bottom of the sea,” and (although he never spells out the allusion) to the characters in Sartre’s No Exit, for whom Hell is other people. In the 1920s he had studied medieval French literature at the Sorbonne, and he brought a long perspective to his reportage. Dispassionately he sums up the historical situation of the old coastal crossroads:

Gaza was captured at various times by Alexander, Pompey, Napoleon, and Saladin, which shows that it must have been considered worth capturing, and during the Middle Ages it was a textile center that gave its name to French gaze and English gauze. Its modern eminence may be gauged by its prison, the largest built by Britain.

Long before Alexander, the Gaza strip enters recorded history late in the 12th century BCE, as one of the coastal cities of Philistia, the “Pentapolis” consisting of Askelon, Ashdod, Ekron, Gath and, the southernmost, Gaza, along the ancient trade routes that connected Egypt and Arabia, Petra and Syria. The Philistines were most likely one of the Sea Peoples, whose arrivals and departures, conquests and defeats, convulsed and enlivened the ancient regime of the Late Bronze Age. Known as the Hyksos in Egypt, which they invaded and briefly ruled, part of their number was supposedly relocated from the Nile Delta to a lonely stretch on the Mediterranean coast after their defeat in battle by the pharaoh Ramses III. Originally (to the extent that the word makes sense in the ever-changing remote past), they were probably Mycenaean Greeks, who came by way of Crete, although far-off Anatolia (modern Türkiye) has also been suggested as their jumping-off place.

In the Old Testament the prophet Amos, some time around 750 BCE, castigates the Philistines in the Lord’s name for enslaving Hebrews: “For crime after crime of Gaza / I will grant them no reprieve, / because they deported a whole band of exiles / and delivered them up to Edom. / Therefore will I send fire upon the walls of Gaza / fire that will consume its palaces.” The Philistines’ afterlife as a disparaging stereotype (“a person who is hostile or indifferent to culture and the arts”: Oxford Concise Dictionary) is owed to a Renaissance misconception, later reinforced by Matthew Arnold and Heinrich Heine. Actually, their city-states were sophisticated for the time and, true to their putative Aegean origins, their black-and-red pottery shines beside the crude efforts of contemporary Israelites.

The Philistines predictably receive unfavorable notice in the notionally historical portions of the Old Testament, most famously in the stories of David and the Philistine giant, Goliath, and the judge Samson and his faithless wife, Delilah. The latter is retold by Milton in Samson Agonistes (1671), which begins with the Israelite hero “eyeless in Gaza,” but recovering his strength in time to pull down the temple on the Gazans who have made a spectacle of his captivity: “The Edifice where all were met to see him / Upon their heads and on his own he pulled.” Milton’s poem ends with Samson’s father, Manoa, resolving to recover his body, “soak’t in his enemies’ blood,” for burial. A local tradition, told to Liebling on his one visit, said that Samson survived long enough to carry the fallen pillars of the temple “to the far end of the crest of Ali Muntar, where admiring posterity has erected a marabout,” i.e., a shrine, “as a marker.”

Toward the end of the eighth century BCE, Philistia and Israel lost their independence to Assyria, the paradigm of Empire in antiquity: “Before me, cities; behind me, ruins,” as one of its rulers proclaimed. After it fell in turn, the conquering Nebuchadnezzar II reached out to add the coastal domain to his Neo-Babylonian Empire. The Philistines were effectively lost to history, returning to the obscurity from which they came. Not so the Judaeans, whose nobility were taken into Babylonian captivity, as lamented in the Old Testament.

In 530 BCE Gaza’s mixed populace fell to the Persian emperor, Cambyses II, the son of Babylon’s conqueror, Cyrus the Great, and himself on the way to the conquest of Egypt, where he left behind a reputation for mad excesses such as slaughtering the sacred bull Apis, some of which modern historians have acquitted him of. Two hundred years after Cambyses, the Macedonian Alexander arrived, similarly intent on possessing Egypt. In the interval, the eastern shores of the Mediterranean had been reshaped by the cultural allure of Hellenism, of the city-state—the polis which Alexander would make the administrative basis of his vast empire. Gaza had grown rich and complacent off the spice trade. Its Persian governor, the eunuch Batis, fondly imagined that the city’s lofty fortifications made it impregnable, while raiding the countryside for provisions would be sufficient to outlast any siege. Alexander’s sieges reliably ended badly for the besieged. After two months Alexander breached the walls with the same moving towers equipped with parapets he had used at Tyre in Phoenicia, where 2,000 of the surviving defenders were crucified. Having narrowly escaped death by an assassin and suffered a wound in the shoulder which kept him from the battlefield, Alexander was exasperated by the time the defeated Batis was brought before him; still defiant, he was dragged by his heels around the city, to his death. The men of Gaza were slaughtered.

In 48 BCE the Roman general Pompey the Great was in flight to Egypt after a conclusive defeat at the battle of Pharsalus in his civil war with Caesar; his legions had been reduced to a disloyal handful by the time he was assassinated while attempting a landing at Alexandria, where its founder was entombed in a crystal sarcophagus at the crossroads. As the prophet Isaiah had declared ages before: “Woe to them that go down to Egypt for help.”

Long before Alexander, the Gaza strip enters recorded history late in the 12th century BCE, as one of the coastal cities of Philistia, the “Pentapolis” consisting of Askelon, Ashdod, Ekron, Gath and, the southernmost, Gaza, along the ancient trade routes that connected Egypt and Arabia, Petra and Syria.

Two thousand years after Pompey’s flight, after the political landscape of the Holy Land had once again been reshaped by global war, the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper asked, “What is the essential, the permanent character of Palestine?” And, guided by the great historical geographer George Adam Smith, answered: “From the first it has been double: Palestine is both ‘the bridge between Asia and Africa’ and ‘the refuge of the drifting populations of Arabia.’” Quoting Smith,

Thus when history first lights up within Palestine, what we see is a confused medley of clans—all that crowd of Canaanites, Amorites, Perizzkites, Hivites, Girgashites, Hittites, sons of Anak and Zamzummim which is so perplexing to the student and yet in such thorough harmony with the natural conditions of the country and with the rest of the history…. Palestine, formed as it is, and surrounded as it is, is emphatically a land of tribes.

In the Middle Ages, Franks, as the Western Europeans were interchangeably known to the Muslims, were added to the mix. For 125 years Christian kings reigned in Jerusalem, their domain approximating that of present-day Israel with, at its peak, notional suzerainty extending northward along the coast to Antioch and Tripoli and eastward into Edessa. Saladin, the great commander who regained Jerusalem for Islam, was born Yusif ibn Ayuyub, on the high Iranian plain but raised in cosmopolitan Damascus. As a youth he was bookish and pleasure-loving, but when duty inevitably called he followed his father and uncle, Kurdish soldiers of fortune, into the service of an ogreish local Turkish despot, Zangi, and later his son, the devout and capable Nur al-Din. In 1164 he joined his uncle Shirkuh in an expedition into Egypt, where the two-century-old Fatimid dynasty was drowning in a sea of troubles, coups, counter-coups, riots, foreign armies. As in Heian Japan, a world away, where the shoguns ruled while the emperors merely reigned, the caliphs, often minors, merely ratified the accession of the vizier who, by whatever means, but usually violent, had risen to be the power behind the throne. Saladin personally abducted the Egyptian incumbent who was paying a ceremonial visit; his severed head was delivered to the latest boy caliph, who prudently rewarded him with the vizier’s robes. “Now the Turks held Cairo with an overwhelming army,” Sir John Glubb summarizes. “In one form or another they were to remain for seven hundred years.”

In a few months his gluttonous uncle Shirkuh, described by Glubb as “short, fat, one-eyed and ugly, but a great fighter and a voracious eater, especially of meat,” died of colic and was succeeded as vizier by Saladin, whose youth recommended him to the Fatimid court; it was thought he would be manageable. As Sir John Glubb fills in the ethnic picture: “To the Muslims every man from the West was a Frank, be he French, English, German, or Italian. The western historians by referring to all the peoples of Syria, Iraq or Egypt as Saracens missed many important factors. These countries were in reality inhabited by races of extremely varied origins. The Arabs were Semitic, the Turks resembled the Mongol type, the Egyptians were partly African, the Kurds are believed to be of Aryan origin. It is, therefore, of interest to note that, in the struggle for power in which Saladin was victorious, he appealed to his fellow Kurds in the army not to allow the command to pass to the Turks.”

In a confused welter of ethnic power struggles between Sudanese mutineers and Turks, Turks and Armenians, Shia and Sunni in Cairo, with the distant threat of a Third Crusade hanging over events, Saladin emerged as the strong man of Egypt, while punctiliously proclaiming his loyalty to Nur al-Din; control of Egypt and its fabulous riches would determine the fate of the region. The cities in the Strip stood in the way. As told by Sir John Glubb, “In December 1170, Saladin took Gaza by assault and an indiscriminate massacre of men, women and children ensued,” really to no point, as it turned out. “When Amaury [the Frankish king of Jerusalem] arrived, Saladin withdrew to Egypt.” When he was not campaigning, Saladin busied himself with fortifying Cairo, which the Fatamids had founded in the 10th century, using the labor of innumerable Frankish prisoners to build the famous citadel. In 1177, when he again set out for Jerusalem, Saladin and his army of 25,000 swept past Gaza, where a few score Templars were garrisoned; always disliking the bother of a siege, he merely invested Askelon, where Baldwin IV, the “leper king” of Jerusalem, was believed to be marooned. Saladin’s advance to the Holy City set the fertile plain on fire as he went marauding. The sultan’s legendary magnanimity to fallen foes didn’t extend to ordinary soldiers; all prisoners taken were immediately decapitated. Near present-day Lydda the path to glory was unexpectedly interrupted when his army was surprised and routed by Baldwin, who had managed to escape from Askelon after all; commanding a few hundred troops of his own, joined by the Templars who came up from Gaza, he launched a frontal assault which sent almost all of Saladin’s men into flight; covered by faithful Mamluks, he escaped on a camel. Jerusalem eventually fell to Saladin in October 1187.

“European historians have contrasted the terms accorded by Saladin with the massacre that marked the capture of Jerusalem by the First Crusade eighty-eight years before,” Glubb writes. “The principal explanation lies undoubtedly in the fact that the Arabs were a civilized people, while the Franks in 1099 were not.”

The possession of Jerusalem went dramatically back and forth until the ferocious conquest in July 1244 by the Tartar cavalry of Barkha Khan, who did not spare even the dead. As Simon Sebag Montefiore writes: “The bodies of the kings of Jerusalem were disinterred and burned yet their elaborate sarcophagi were somehow spared; the stone at the door of Jesus’ tomb was shattered… Smouldering and smashed, Jerusalem would not be Christian again until 1917.”

History decreed the old coastal cities would continue to pay the price of their strategic location, taken by foreign armies bound for Alexandria or Jerusalem. Just four years later King Louis IX of France, later canonized, mounted a crusade, only to be captured with his troops by Mamluks, who soon after overthrew Saladin’s dynasty in Egypt. In 1258 the Mongols burst upon the horizon from the east. “They took Damascus and galloped as far as Gaza, raiding Jerusalem along the way.” And so it went.

In 1798 the 29-year-old revolutionary general Napoleon Bonaparte marched northeast from Egypt, which he called “the most important country in the world,” as part of a grand never-to-be-realized design to conquer the East from the Nile to India. It was the first military intervention in the Middle East by a European power since the Crusades, and in its opening feint he marched toward Syria, following in the ancient routes that Saladin had taken. Pacifying the local authorities whom he promised to liberate from England’s yoke turned out to be a more complex matter than he hoped, and his capture of Jaffa was marred by an atrocity, when he ordered the shooting of 3,000 prisoners, possibly because they couldn’t be fed. Plague had reduced Bonaparte’s “invincible” army by half when it staggered back to Cairo, and he might have been relieved when he was recalled by the Directory in Paris to fight other battles. Nonetheless, and especially after exile gave him leisure, he would say he “missed his destiny in Syria,” but that Egypt was “the finest time of his life, because it was the most ideal.” After Napoleon’s departure, Ottoman dominion in the Middle East was restored, though compromised by concessions to Western powers, most significantly in Egypt, which was effectively a British protectorate after 1882.

In Gaza Liebling made the acquaintance of an older man who brought an informed perspective to its history. General Refet Bele, whom he befriended, had commanded the Ottoman army corps that defended the city from the British, who repeatedly laid siege to Gaza in 1917, succeeding on the third try. A “small, thin man with a falcon’s head,” 75 years old, dapper in a checked suit, General Bele now represented Türkiye on the advisory committee of UNRWA, a position which carried ambassadorial rank. They talked on the terrace of a pension in a new, undamaged part of town favored by prosperous landowners.

“‘When I defended Gaza,’ [Bele] said, ‘I left it completely flat. Not one house—not the least one—was left standing.’ He moved his right hand in a horizontal arc, palm down. I could see that he was flattered by the deterioration in the quality of war since his day.’”

Obliging Liebling, the old Turk recalled Palestine in the days of the Ottomans: “‘A country of pastoral happiness, where everyone slept on both ears every night. Jew and Arab and Christian lived together in security. They felt they had had a father.’” (That would have been Abdul Hamid II, the sultan and caliph known to the Western press of his time as “The Damned.” ) “He felt that the British fomenting of Arab nationalism had opened Pandora’s box, and he regretted the passing of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires.” The old autocracies were comparatively weak, but allied to Germany, “they balanced the colossus Russia.” The Great War’s unbalancing of the powers had led straight to the present catastrophe, which he, General Refet Bele, would not be witnessing for long. His life was elsewhere, and one of UNRWA’s planes from Beirut would soon put him on the way back to it. The two spoke in French, a language the general had learned from reading the novels of Pierre Loti and Paul Bourger, while stationed in the wilds of the Caucasus when he and the world were young.

Sources:

A. J. Liebling’s “Letter from Gaza (On Refugees in the Strip)” was published March 16, 1957, in the New Yorker, and is collected in Henry Finder, The 50s: The Story of a Decade (New York, 2015). There are numerous editions of Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869); there are not of Melville’s 1857 travel journal, which became the basis of his poem, “Clarel” (1870), but it can easily be accessed online. The minor prophet Amos is quoted from The New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition (New York, 1976). Other sources and further reading as follows:

H. R. Trevor-Roper, “The Holy Land,” collected in Men and Events: Historical Essays (New York, 1957).

Peter Mansfield, A History of the Middle East, 2nd edition, revised and updated by Nicholas Pelham (London, 1991).

Felix Markham, Napoleon (New York, 1963).

Sir John Glubb, The Lost Centuries: From the Muslim Empires to the Renaissance of Europe, 1145-1453 (London, 1967).

Simon Sebag Montefiore, Jerusalem: The Biography (New York, 2011).

Eugene Rogen, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East (New York, 2015).

Eckart Frahm, Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Empire (New York, 2023).

Nur Masalha, Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History (London, 2021).

Gudrun Kramer, A History of Palestine: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Founding of the State of Israel, translated by Graham Harman and Gudrun Kramer (Princeton and Oxford, 2008).