[drop-cap]

On September 19th, 2003, Channel 4 aired the first episode of the future. The British broadcaster probably didn’t realize they were offering a peek into our new media landscape. But Peep Show—which went on for nine more seasons—is still ahead of its time, ten years after its finale.

Created by Sam Bain and Jesse Armstrong (who later wrote the satirical, rich-people nature documentary Succession), Peep Show was a critical darling, but never a big hit. But what makes Peep Show so special—and so prescient—isn’t its bleak situational comedy or its loathsome protagonists. It’s its style.

Filmed entirely in first-person, the show places viewers within its characters’ heads. It lets you experience, first-hand, the unfolding narrative of Mark and Jez’s laughably dismal lives. As essayist Emmett Rensin wrote on the show’s conclusion:

“Their eyes are your eyes. Their pain is your pain. If one objective of narrative art is to draw the viewer into conspiracy with the desires of its characters, then Peep Show succeeds in a manner rivaled only by pornography.”

That comparison, of narrative art with pornography, reveals its immersive power. You don’t watch Peep Show so much as inhabit it. Its character arcs aren’t consumed, but experienced. Along with first-person video games—and yes, porn—Peep Show may be the foundational piece of visual art for the coming century.

In a world where terrorists strap cameras to their heads, where children don headsets to simulate their own modern warfare, and where talent agencies tap “faceless” influencers to sell new products, the fictional mode of Peep Show—of total immersion in another’s experience—is quickly becoming the norm.

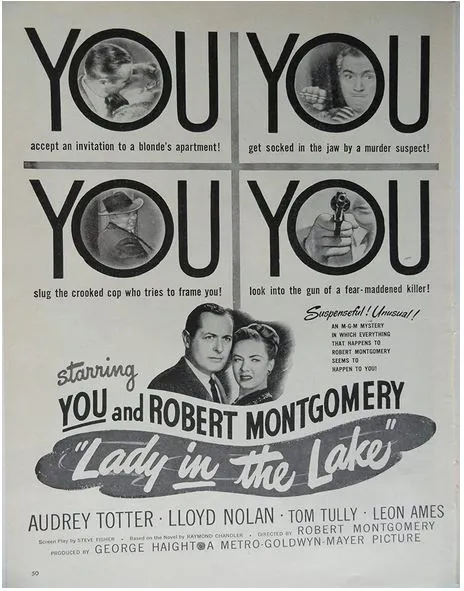

Peep Show may have perfected the first-person POV, but it didn’t invent it. Napoleon, a five-hour epic from 1927, is considered the first. Using a hand-cranked Parvo, director Abel Gance took the camera on horseback and into fist fights. Later, the technique became a staple of Golden Age Hollywood, often serving as a cutaway shot. But in 1947, actor Robert Montgomery became so enamored with the perspective that he directed the first feature to be entirely shot in POV: an adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s Lady in the Lake.

Reviews were mixed. Critic Thomas Pryor wrote that the production’s novelty quickly wore thin. But he also noted that, by “making the camera an active participant,” Montgomery had discovered something genuinely new.

Indeed, MGM’s marketing department understood this better than the critics. Advertisements in Life Magazine promoted the film’s immersive promise: “YOU accept an invitation to a blonde’s apartment! YOU get socked in the jaw by a murder suspect! … YOU look into the gun of a fear-maddened killer!” The copywriters even gave “YOU” top billing.

Still, the technique didn’t catch on. But the new millennium saw rekindled interest in first-person filmmaking. Groundbreaking music videos like The Prodigy’s “Smack My Bitch Up” (1997) paved the way for the mixed POV production of Being John Malkovich (1999). Following Peep Show, Enter the Void (2009), Hardcore Henry (2015), and Presence (2024) all used the camera as a participant in their stories. However, none received quite the fanfare as 2024’s Oscar-nominated Nickel Boys.

Adapted from a Colson Whitehead novel, the film was praised for its use of first-person photography. Director RaMell Ross and cinematographer Jomo Fray chose to follow their protagonists—two black boys at a racist, murderous “reform” school in mid-century Florida—almost completely from their points of view.

Yet, the filmmakers distanced themselves from the term. Speaking to The New York Times, Fray described it instead as “the sentient perspective,” meant to produce images that felt like seeing, rather than simply representing sight. In other words, the photography needed to feel embodied. It needed to be immersive. They asked “what if the characters had a camera like an organ attached to their eyes the entire time? … What would it look like? What would they see?”

The truth is, we already have these organs. They’re called phones. And while Nickel Boys is an audacious adaptation, it is not unprecedented. Ross and Fray have not “reinvented the act of seeing,” despite the Academy-baiting coverage. Because the deeper truth is that cameras have stood in for human experience since the dawn of filmmaking itself.

Looking back at the work of Auguste and Louis Lumière—the godfathers of cinema—it's clear that the first-person perspective has always been there. In 1895, their audiences were astounded as black-and-white images flashed by: workers leaving a factory, blacksmiths forging, passengers disembarking a riverboat. It didn’t matter that the artifice was clear—it felt as if you were really there.

The footage still fascinates. Subjects stare through the lens, making eye contact across two centuries. At one point, a photographer hesitates. He sees you, watching him, watching you. Then he snaps a photo and hurries off. By raising his lens against another, the photographer seemed to grasp something: that the camera’s existence presupposes immersion in a photographic world. To see—and to imagine yourself being—another person, in another place, at another time, is fundamental to the medium. First-person productions like Peep Show and Nickel Boys take this to its natural conclusion.

The problem, of course, is that watching something and experiencing it are two different things. By conflating watching with being—consumption with experience—first-person entertainment shifts where we draw the line between art and life. Becoming embodied in the camera’s world, rather than the physical one it reproduces, allows cinematic experience to leave the screen and enter the mind. It’s a feedback loop, where the logic of entertainment informs the ways we see, the ways we feel, and ultimately the ways we act—where narrative art is no longer something to watch, but something to be immersed in.

And as Peep Show demonstrates—with protagonists that cheat, lie, stalk, and sleep with future mothers-in-law—immersive entertainment sets a low bar for depravity.

On March 15, 2019, an Australian ethnonationalist started a Facebook Live stream. “Let’s get this party started,” he said, speaking directly to a helmet-mounted GoPro. Twenty minutes later, he donned the helmet, checked his semi-automatic, and proceeded to kill 42 people at the Al Noor Mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand. Four thousand viewers watched it live, before it was re-uploaded millions of times by a “dark fandom” online.

The shooter’s presentation of genocidal brutality as live entertainment—and his use of equipment straight out of Peep Show—may seem surprising. It shouldn’t. As Jason Burke and Graham Macklin, two British researchers, have pointed out:

“His video was not so much a medium for his message insomuch as it was the message... The central point of his attack was not just to kill Muslims, ‘but to make a video of someone killing Muslims.’”

The point was to tap into an audience. To be seen. To be witnessed.

Terrorism may seem like it has a tenuous relationship to the sort of first-person entertainment discussed until now. But, again, it shouldn’t. For both jihadists and lone-wolves, immersion is the goal.

By recording their violence, by acting out ideological narratives with the camera as an active participant, terrorists package their messages as entertainment. Their crimes must be dramatic. Gut-wrenching. Immersive. Viewers must imagine themselves in the frame. Without an audience, terror becomes worse than meaningless. It ceases to exist.

In a way, terrorists are influencers. They have their followers on Telegram and Discord, waiting for their next batch of “content.” Their actions are like clips from a blockbuster or a video game. They talk of kill counts, and leaderboards, and getting the “high score.” And their power depends on everyone playing the same game as them.

Enjoying your dinner? Shoot a photo. Going to a concert? Shoot the band so everyone knows you were there. Driving past a demonstration? Shoot the protestors. Feeling cute? Shoot yourself.

Much has been made of the Christchurch shooter’s video game references. They pepper his manifesto. The livestream itself has a superficial likeness to first-person shooters—one of the industry’s most popular genres. But video games have ignited moral panics since Columbine, without substantial evidence to what role (if any) they play.

Still, any genealogy of first-person entertainment would be incomplete without them. Games like Wolfenstein 3D (1992) and Doom (1993) set the stage for a format that shifts millions of units every year. By embodying players in their simulated environments, first-person shooters primed an entire generation to treat images not as things to be observed, but worlds to be interacted with. In their quest for immersion, game designers adopted the same camera-as-bodily-organ framing that Nickel Boys would use decades later.

The more you look, the more you see this framing—of the lens as an access point to experience—supplanting other forms of engagement. In fact, the mechanics of first-person shooters aren’t so different from the gamified relationships our phones encourage in our daily lives.

Enjoying your dinner? Shoot a photo. Going to a concert? Shoot the band so everyone knows you were there. Driving past a demonstration? Shoot the protestors. Feeling cute? Shoot yourself.

The “creator economy” depends on users seeing their lives through the camera lens. Experiences must be shot, flattened, and filtered before being validated on screen. Yet, phones are clunky instruments for immersion. They must be pulled out, unlocked, and held. Even if users are already embedded within their cameras’ worlds, they still have to physically place their devices between them and their experience. Phones are both doors and windows: something to be opened and closed, and something to be looked through to see outside.

But if Silicon Valley has its way, phones will soon be your grandma’s way of seeing the world.

In 2013, to near-universal nerd-bashing mockery, Google released its first augmented reality headset. But Google Glass, which looked more like orthodontic headgear than a pair of glasses, never had a chance. The term “glasshole” appeared overnight, describing those early adopters brash enough to submit every waking moment to tech bro surveillance. Within two years, Google ceased production and the Great Glasshole Crisis was averted.

Or was it?

Looking back at contemporary coverage, it’s shocking how far the cognitive landscape has shifted. Charles Arthur, former technology editor at The Guardian, couldn’t see a compelling use case. In what now reads as a bewildering aside, he wrote: “Most people don’t walk around needing to Google things.” And the frequently cited “privacy concerns” come across as a joke in the age of TikTok. Today, recording yourself and the people around you isn’t a concern--it's an imperative. Although Google failed to market Glass, the ideas behind it never went away.

In fact, smart glasses are quietly gaining popularity. Last year, Meta (Instagram’s parent company) sold over a million of them. By partnering with Ray-Ban, Meta did what a thousand dorky betas couldn’t: they made their users look, if not cool, then at least normal. The behaviors that marred glassholes are now commonplace.

Consider the growing niche of “faceless” influencers. These social media power users broadcast first-person views of their lives to millions, performing quotidian tasks like shopping, or painting their nails, or organizing their homes. Their lifestyles, rather than their carefully maintained images, are the draw. But even faceless influencers have faced the same problem that confronted the glassholes: how to avoid looking like an utter dweeb. The most common solution--a mount worn around your neck--almost makes Glass seem stylish.

Yet, as eyewear manufacturers continue to strike deals with tech companies, smart glasses are poised for widespread adoption. Soon, millions will be recording their dog walks and their nights out, ready to upload their first-person experiences on a whim.

Most of this content will be somewhere between bland and unobjectionable. But not all. In another horrific example of where this is going, the man responsible for the New Year’s terror in New Orleans was wearing Meta’s smart glasses during his attack, but may have botched a livestream along with other parts of his plan.

One day, the styles and capabilities of these devices will merge with those of modern phones. When smart glasses have their “iPhone moment”—becoming ubiquitous, must-have products—first-person entertainment will leap from immersive pastime to daily ritual.

By assuming the camera’s gaze as our own, our mundane experiences will move closer to the language of films and video games, leading to a kind of cultural immersion that erases the already flimsy boundary between media and self. To stream something and to be something will no longer be at odds, but two parts of the same thing.

Smart glasses, in other words, represent the end of the fourth wall. And if you look at their budding popularity as its dissolution, the chaos of the modern world comes into focus.

But if Silicon Valley has its way, phones will soon be your grandma’s way of seeing the world.

For a time, Luigi Mangione was the most famous man in America. After allegedly killing the CEO of United Healthcare in December, he took police on a week-long, made-for-TV goose chase that dominated the news. But the murder, while brazen, was not unusual in a country that’s seen a dozen attempted (and four actual) presidential assassinations. However, the response to it was.

Every step leading up to Mangione’s arrest seemed planned with its entertainment value in mind. In his evasion of the police, and in the taunting clues he left behind, Mangione put on an unfolding, media-savvy performance that scratched many viewers’ true-crime itch—while explicitly targeting one of America’s most-hated industries: for-profit healthcare. Given the symbolic weight of his actions, it’s clear that Mangione had been swept up in the multiple, intersecting media narratives that define modern American life. And by violently inserting himself into these narratives, he became the main character not only of his own story, but everyone else’s too. By playing life in the first-person, Luigi Mangione left the fourth wall behind.

Call it “First-Person Syndrome”: where total immersion in mediated environments leads people to believe they’re at the vanguard of cultural change—the main characters in their personalized national narratives. It’s a performance that terrorists know well. Armed with a camera and some talking points, anyone can play-act the modern revolutionary. Never mind that most of us aren’t rushing out to murder CEOs—we're still a mere POV shift away from the role of a lifetime.

Mangione wasn’t wearing smart glasses at the time of his alleged crimes. But imagine he was. Imagine a future, decentralized social network containing millions of first-person livestreams, all going at once.

What if you could have been there, as it happened? What if you felt like the main character? Would you feel remorse? Or would you maintain righteous indignation?

What if you already had an audience? What if, rather than seeking revolutionary change, you were simply playing a role? That of the real-life “culture warrior.” Actions that in another century would be deemed “propaganda of the deed” are instead more like “normalization” or “commodification” of the deed, where profound acts of violence become just another way to gain followers.

It’s not as strange as it sounds. Mass shooters who’ve survived their massacres admit they were competing with each other, as if life was a first-person shooter. Understanding Brian Thompson’s murder as a quest for viral celebrity reveals the immersive media environment we already live in, and how the demands of narrative entertainment have set the terms of engagement.

This is why books like The Image, The Society of the Spectacle, and Amusing Ourselves to Death have been rediscovered in recent years. They explain the feeling that we’re living through gateways to another reality—that the world of images is now more real than the one we wake up to. But it doesn’t matter what’s real. What matters is what’s entertaining.

As Hollywood struggles for relevance in a first-person world, courting AI companies in the hopes of cutting jobs, studios may be surprised to learn that viewers still prize humanity in their entertainment. This isn’t to say that entertainment will be wholesome, it’s that viewers prefer personal stories that show people at their most human. That’s how a privileged thirst trap who suffered a familiar injury can become a folk hero overnight.

The coming wave of first-person influencers will be like Luigi Mangione. They’ll be the people that do what the rest of us won’t. They’ll be the extreme athletes, the attractive criminals, the act-first-think-later rebels who live life like it’s a movie. They’ll live outside the law, but within the system, in a theatrical production somewhere between QVC and Columbine. And their exploits will probably seem as outlandish to us as OnlyFans would to someone at the turn of the century.

For what they’ll be doing, look back to Peep Show. In one episode, due to a broken door and a planned magic-mushroom party, Jez forbids a diarrheic Mark from using the toilet. With no other options, Mark considers relieving himself in a bag. But what would he do with it? Hide it? Throw it out? No, he thinks, “that’s where society’s headed: people shitting in bags and throwing them out the window at each other.”

Sounds like compelling first-person content.