Last September, the Democracy Seminar at the New School for Social Research published “Fatigue-Resistant Resistance” by the writer and educator Dinah Ryan. In the first part of the essay, Ryan takes stock of our contemporary political moment, likening President Trump’s “upending of democratic society” to what the Czech playwright Václav Havel called a “post-totalitarian” society, wherein ideological systems suppress freedom of expression by controlling the media and normalizing lies. In the second part, Ryan offers her idea of “soft networks,” a model, she says, “for maintaining resistance and hope in the face of this totalitarian onslaught.” I spoke with Ryan about her vision for the “soft networks” project earlier this month, two days after an ICE agent shot and killed the legal observer, Renee Good, on the streets of Minneapolis. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

SKY O’BRIEN: In “Fatigue-Resistant Resistance,” you frame “soft networks” as a form of civil and political resistance in a “post-totalitarian” society. Before we explore soft networks, could you unpack this idea of the “post-totalitarian” and how you see it being played out in the United States today?

DINAH RYAN: When you hear a term with the prefix “post-” in front of it, your first reaction is to think it means after something has happened or, potentially, after that thing has gone away. “Post-totalitarian” means exactly the opposite. It means after totalitarianism has been established in pervasive, multifarious ways throughout the globe in varied localities and nations. Václav Havel, writing in The Power of the Powerless when the former Czechoslovakia was under communist rule and dominated by the Soviets, used the phrase “post-totalitarianism” to suggest a totalitarianism that doesn’t look like a conventional dictatorship. As in China’s current government or Hungary’s government, post-totalitarianism can materialize through elections, capitalist systems, oligarchies, and other kinds of suppression centrally located in a government that oppresses and controls the systems under which people live. That includes the spectacles of consumerism and market-driven media saturation, which—in the United States, anyway—provide a false veneer of normalcy. We’ve got our stuff and we’ve got our screens, so we’re satiated and carry on as if everything can at least return to normal, even though we have already tilted precariously toward a totalitarian system. Many citizens—hopefully most citizens—are deeply concerned at the blatant attacks on democracy over the past year. Havel tried to articulate what such ordinary, “powerless” human beings might do in those circumstances.

I also think that many people don’t think that the United States can become a post-totalitarian state. There’s a feeling that things will go on as they always have, with free elections bringing changes mandated by the citizens. But we have elected someone who has totalitarian aspirations, who is foolish, power mad, and both narcissistic and egotistical. We have done this because we have what M. Gessen calls a “failure of imagination.” Back in July 2016, before Donald Trump’s first election, Gessen wrote an essay for the New York Review of Books in which they pointed out that Trump’s totalitarian aspirations were boldly obvious and that he had the potential to be more Putin-like than Putin. In that essay, they referred to “failures of imagination,” specifically to the failure to understand that Trump was not being manipulated and was extremely dangerous. And I do think that’s something we’re struggling with in the United States right now, that a great many people just can’t imagine the United States will ever be anything other than democratic, ever be anything other than one free election from changing course. I also think there are people who would prefer not to have democracy at this point, but that’s a much more complex conversation.

I grew up in the South. I had grandparents in Arkansas, Tennessee. And I spent the better part of my childhood and young adulthood in Virginia, where I now still live. The concept of states’ rights that I was aware of growing up was the very conventionally conservative notion that the federal government didn’t have the right to impose social or economic mandates on the states. And often that meant, as it did in Virginia, the right to ignore, for example, Brown vs. Board of Education and not racially integrate the school system or to have right-to-work laws so that unions couldn’t be formed. On some level the concept of states’ rights hasn’t changed much. Many red states (think “Texas,” “Iowa,” “Missouri”) are still using states’ rights to suppress inclusion—for the purposes of voter repression, for obstruction of due process, marriage equality, reproductive rights, etc. (even as they applaud brutal federal overreach in places like Minneapolis, Portland, LA, etc.). But states’ rights has also come to mean, in many states around this nation, the right of localities—and the right of people at the state and local level—to support democracy and to oppose and forestall a totalitarian fascist-like government. That shift reflects part of what’s been important to me about the “soft networks” concept, that individual citizens can take a stand right where they are.

You write about the fatigue that comes with being a citizen in a post-totalitarian society. Trying to make sense of these changes and knowing how to respond to government suppression is tiring, demoralizing. The “soft network” aims to give individuals a model for engaging in political resistance in a way that resists fatigue and confusion. Could you expand?

In his second administration, Donald Trump has moved with rapid fire belligerence to keep us destabilized. People feel tired, shocked, helpless and constantly on edge. And that is by design: we are supposed to feel overwhelmed and insignificant. And we’re supposed to get used to living this way. That’s what the communists in Czechoslovakia after 1968 called “normalization.”

When Trump was elected, I decided that, as an individual human being, I could not give up. For over a decade, I co-directed study abroad programs in Prague and the Czech Republic, and the knowledge of historical totalitarian systems I had gained from that work made me keenly sensitive to what could happen here after the 2024 election. And, in part because of all the former students who had to confront the terrors of twentieth-century authoritarianism with me on that program, I decided I could not give in and I started to think about how I might do that.

The first thought I had was that I’m just an ordinary person. And by being an ordinary person, I don’t mean that I’m a person without significant events in my life. But essentially I’m not important. I’m not a public figure. I’m just an ordinary person who has to get up every day and get through my day. In the grand scheme of things, no one really cares what we, ordinary American citizens, do.

As I thought about this ordinariness, the phrase “soft networks” kept popping into my head. I Googled it, and I found a reference to the kind of networking that people do when they’re looking for work. I found the name of a nonprofit arts organization. That wasn’t what I was looking for. I began to do academic research and I discovered there is a concept in the material sciences called “soft networks.” The term refers to the construction of artificial web-like fabrics that mimic human tissues, developed through collaborations between physics, chemistry, biology, neurology, and engineering. These “soft networks” mimic human skin, heart tissues, ligaments, and so on. And they can be used to heal and repair the body, to give the damaged body the capacity to move again and stretch and bend and work in ways that it couldn’t otherwise. I thought, Oh, well, I must have read that somewhere, and it was floating into my consciousness. It was the concept I was looking for.

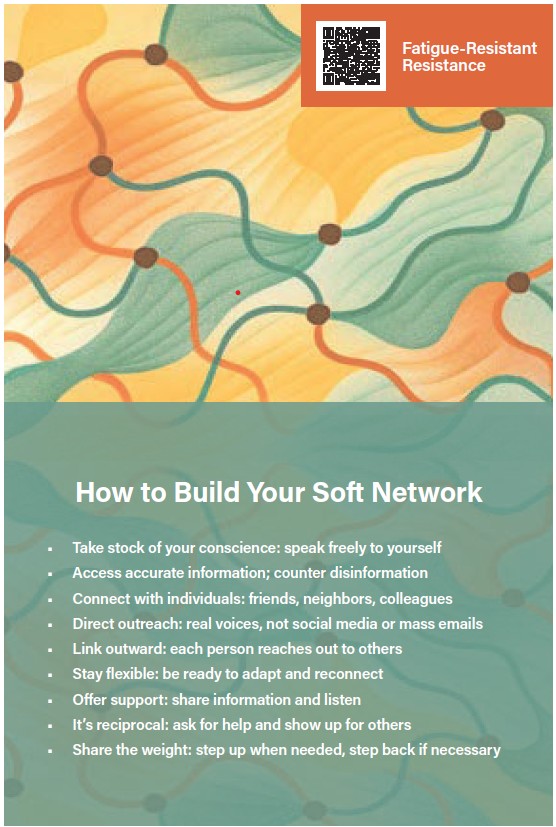

So for me, soft networks means individual, ordinary, seemingly inconsequential human beings forming webs of support. For instance, you might say to me, this is something that I am concerned about in our country or in our community, or here’s an issue that I think needs support. And because we are linked up and because we trust each other, I can say to you, I will support that. I will do something to help. And I can do the same thing with you. Trust is an important piece of this process. There’s a fundamental need for trust and honesty and accurate information inside these soft networks. What I envision is a grassroots model by which people who are being honest with themselves and with others and who persist in learning how to find and share accurate information, can turn to one another and support one another in times of need.

Yesterday, J.D. Vance gave a press conference in which he brazenly lied and said that Renee Good had been trying to run down the ICE officer who shot her. He said something like, When people throw bricks at law enforcement officials or when people try to run down law enforcement officials, there is a well-organized left wing terrorist group that is organizing and sponsoring all of this. Vance’s words are a bald-faced lie. That’s a fascist tactic, a totalitarian tactic. I’m quite sure he knows it’s a lie, but not everyone will accept it as a lie. But as I listened to him say this, I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting—and quite a shock to the system—if the real resistance was a broad web of ordinary individual people who simply will not give up on the truth?

A soft network begins with individual nodes–with people like you and me–who want to link up with other individuals. But you offer a two-step method for each individual who wants to make or join a network. First, one needs to commit to “unflinching, honest thought and speech.” Second, one needs to make a “direct person-to-person web of mutual support that they can actively maintain and adapt.” Why are these steps so important to the soft network?

That’s a fundamental question. First of all, I don’t think this idea is new. Many people are already doing this kind of work intentionally in organizations, in activism, and in civic virtue. And there are many people, such as M. Gessen and Anne Applebaum, who are speaking knowledgeably and clearly about what is happening and about the consequences of Trump’s administrative actions.

But there are many people who are not involved in resistance and many, many people who simply feel helpless and hopeless. My hope with the soft networks project is to add more conscious attention to what to do in the face of growing authoritarianism, and to develop one kind of path for maintaining freedom of thought on an ongoing, daily basis. I believe the concept speaks in a practical way to something that people are trying to do anyway but often haven’t fully articulated for themselves. It also suggests a specific means of building active webs of support that are not connected only to organizations and events such as protests.

Secondly, “soft networks” is not an optimistic idea, although I think it's a means of retaining hope. My reading on the current situation is that it has tipped past the point of danger to overt emergency on a national and global level. ICE is shooting people, people are being disappeared, we are tilting toward warfare internationally, information is being suppressed and misinformation is being widely disseminated. So, forming a soft network is a dangerous thing to do. It takes bravery.

As for why the two steps in the “soft networks” process are so important, first and foremost, the intention to understand oneself is absolutely necessary. If I am spending my days doing things that are self-soothing, for example, rather than paying attention to what’s going on in the world, or if I am being complacent, I have to be honest with myself about that.

I know someone who is both a philosopher and a mental health professional. When they read a draft of “Fatigue-Resistant Resistance,” they said, “I don’t know what you mean by assessing your own conscience.” I find that orientation alarming because isn’t that what the conscience is, actually? That little voice in your head that says, Look, be honest with yourself. You’re running away from this thing, or, you weren’t honest about that, or, you’re making excuses, or, you just don’t want to think about it?

In his second administration, Donald Trump has moved with rapid fire belligerence to keep us destabilized. People feel tired, shocked, helpless and constantly on edge. And that is by design: we are supposed to feel overwhelmed and insignificant. And we’re supposed to get used to living this way. That’s what the communists in Czechoslovakia after 1968 called “normalization.”

I worry that this part of the project sounds judgmental, but I think to be honest with oneself, one has to bring a kind of judgment to oneself. I want to hold myself to that standard. I hope my fellow human beings will be willing to ask themselves, Am I cheating a little bit on facing what’s going on right now? Fear is another thing you have to look at to assess your own conscience. Personally, I need to at least acknowledge the fear and not just turn away, saying, I can’t bear to think about this. Assessing your own conscience means holding yourself accountable when you want to escape or look the other way or feel helpless or simply outraged, as if that were enough.

The other part of being honest with yourself is staying informed and searching for accurate information. That’s becoming harder and harder. There’s a concept called “the liar’s dividend,” which refers to the way in which those who spread misinformation or disinformation can deepen lies by asserting that factual information is false. For example, J.D. Vance et al and the falsifications about Renee Good’s murder. The bonus, the dividend, for the liars is the capacity to strengthen the lies by denying the actual and abundant video evidence to the contrary. The liar’s dividend has been aggravated by social media and also by the assaults on accurate reporting in the press. This escalating sense of living inside of lies has to be resisted—as Havel knew all too well in the predigital days of communist suppression in Czechoslovakia. So things are worse now in this respect.

It is possible to resist, however. For example, Casey Fiesler, who is a professor of Information Science at the University of Colorado Boulder, has spoken about the librarian’s dividend and the ethics necessary for data, information, technology, etc. My own ongoing steps in that direction are to constantly establish and reestablish processes for determining how to check the accuracy of reporting, of information, and of knowledge by verifying that sources can be trusted and by increasingly using libraries that are openly not allowing themselves to be suppressed.

I think without this first, individual, solitary step—of retaining a clear, informed consciousness for oneself—this project doesn’t work.

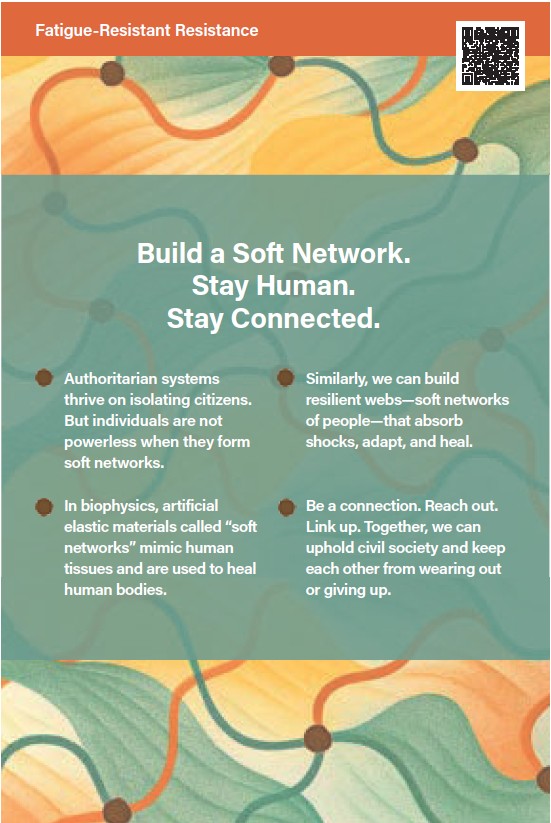

That invitation to take stock of your conscience, to speak freely to yourself—that’s the first bullet point on the “soft networks” postcard that you designed to accompany the project. Can you talk about the postcard—a beautiful physical object—and why you made it?

I thought about the postcard before I thought about the article. I wanted to have something I could share. I have former students who live all over the place, and many of them have been so distressed by the things that are happening. Some of those students are trans. Some of those students are in gay marriages and are concerned about marriage equality. Some have been the victims of racism and sexism. My former students care deeply about the arts and the humanities. They care about other people and many of them are active in their communities and their commitment to civic virtue. When Trump was first reelected and I first had this idea, I thought immediately of my former students and the fear that they might be feeling.

Then I started to think, Oh, I need to really understand what this means for myself. And so I began to write “Fatigue-Resistant Resistance.” Once the article was published, a wonderful graphic design studio, Queen City Creative, produced the postcard for me. The designer used the graphs in the scientific articles about soft networks as an inspiration for the beautiful visual image that suggests these linking, shifting, skinlike webs of mutual support.

The postcard is a non-digital object that I can give to you and that you can give to other people. In my imagination, I am a point in a physical web and I give this non-digital object to other people who form a rhizomatous web with me. They give this non-digital object to other people and form non-digital webs, and that grows.

How can people get a copy of the “soft networks” postcard?

I have a PDF version of the postcard. People can go to my website. If they send me a message on the contact form with their address, I can send out some physical postcards. I hand them out, I give them to friends, I send them out when I write letters.

Anything else you’d like to say that hasn’t been addressed?

I’d like to say more about “ordinariness” and why I think it’s so important. In the public imagination, the “ordinary human being” tends to fall onto one end of a spectrum: the ordinary person who is heroic, on the one hand, vs. the ordinary person who, sheeplike, acts obediently in accord with a web of evil (what Hannah Arendt called the “banality of evil”). While both of those models are true, they aren’t commonplace. Most people don’t have or seek opportunities at either end of that spectrum. They lead mundane lives in which dramatic events seem remote from daily routines—tending to family, work, health, and so on. You know, there’s that feeling that there’s nothing going on politically in the world of immediate experience. And that contributes to the feeling that you can’t do anything. I read and hear this all the time: what can I do? I feel so helpless. And that’s also, I think, why complacency, self-soothing, fear, or failures of imagination can take over. But I also believe that this is why what I have taken to calling the “extraordinary ordinary” is vital. I don’t believe that any authoritarian government—or let’s say a government with blatant authoritarian aspirations—can suppress a nation where the majority of individual citizens hold firmly a commitment to telling the truth to themselves and others, to forming trustworthy webs of mutual support, to democracy, social justice, and civil society.

Of course not everyone can or will do this. All webs are mesh-like, with gaps and holes. And life does intervene. It is and it’s going to be a messy, organic process. But each person who acts as a node in soft networks is doing something quiet but powerful on a day-to-day basis, even if it looks on the surface like there’s nothing going on. I ask myself and ask others not to despair or give up but to commit to this foundational process. I think this is a first bulwark against our current experience and, ultimately, a last line of defense, which I hope cannot be broken.